Standard 1.1: The Government of Ancient Athens

Explain why the Founders of the United States considered the government of ancient Athens to be the beginning of democracy and explain how the democratic concepts developed in ancient Greece influenced modern democracy. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T1.1]

Explain the democratic political concepts developed in ancient Greece: a) the "polis" or city state; b) civic participation and voting rights, c) legislative bodies, d) constitution writing, d) rule of law. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [7.T4.3]

FOCUS QUESTION: What Parallels Can We Draw Between Ancient Athens and United States Democracy and Government Today?

As a political system, democracy is said to have begun in the Greek city-state of Athens in 510 BCE under the leadership of Cleisthenes, an Athenian lawyer and reformer. Some researchers contend democracy emerged much earlier in the republics of ancient India where groups of people made decisions through discussion and debate (Muhlberger, 2011; Sharma, 2005).

Cleisthenes, the father of Greek democracy |

Cleisthenes, the father of Greek democracy |

"Cleisthenes Bust" by Ohio StateHouseOnly free adult men who were citizens – about 10% of the population – could vote in Athens' limited democracy. Women, children, slaves, and foreigners were excluded from participating in making political decisions. Women had no political rights or political power. Aristotle, in “On a Good Wife,” written in 330 BCE, declared that a good wife aims to "obey her husband; giving no heed to public affairs, nor having any part in arranging the marriages of her children.

"Hydria illustrating three women (ca. 430 BCE.)" by Dorieo is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

A hydria is a three-handled water vessel

Manner of the Kleophon Painter, Kerameikos Archaeological Museum in Athens

Ancient Athens also depended on many markedly undemocratic practices. Slavery was essential to the operation of society; slaves did much of the work of daily life as cooks, maids, miners, porters, and craft production workers. The practice of ostracism allowed citizens to vote a man into exile for ten years without appeal. Women had “virtually no political rights of any kind and were controlled by men at nearly every stage of their lives” (Daily Life: Women’s Life, Penn Museum, 2002, para. 1).

There were significant differences in women’s roles in Athens and Sparta. Athenian women could not own property nor did they have access to money, while women in Sparta could own property, inherit wealth, could get an education, and were encouraged to engage in physical activities. Explore a resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Women and Slaves in Ancient Athens for a fuller comparison of women’s roles in Athens and Sparta.

How did the political practices of ancient Athens impact how democracy became established in the United States? The modules in this topic consider that question in terms of 1) the emergence of modern-day digital government and the realities created by the COVID-19 pandemic, 2) the impact of the Olympic marathon on Native American runners, and 3) the efforts of students and teachers to make school classrooms more democratic places and spaces.

1. INVESTIGATE: Athenian Democracy and Democratic Digital Government in the 21st Century

The word “politics” is derived from the Greek word “polis,” meaning "city." To the ancient Greeks the "city" was a geographic location, and also a political entity. To live in the city meant to be actively involved in making political decisions for the city. In ancient Athens, it was only male citizens who could vote that were allowed to engage in politics. Today, the term politics more broadly refers to all the activities (including cooperation and conflict) among people that create and maintain a government.

A Foundation for Democracy

Athens' "first democracy," limited though it was, operated on two principles new in world history, namely that "we all know enough to decide how to govern our public life together, and that no one knows enough to take decisions away from us" (Woodruff, 2005, p. 24). That system had seven features that over the centuries became the foundation for people's efforts to create democratically self-governing communities, organizations, and nations:

- Freedom from tyranny

- The rule of law, applied equally to all citizens

- Harmony (people adhering collectively to the rule of law while accepting differences among people)

- Equality among people for purposes of governance

- Citizen wisdom built on the human capacity to "perceive, reason, and judge"

- Active debate for reasoning through uncertainties

- General education designed to equip all citizens for social and political participation (quoted in Sleeter, 2008, p. 148)

The political practices of Athenian democracy are relevant to understanding how democracies function in the world today. Although severely limited, there was civic participation, voting rights, and legislative bodies (the Assembly and the Council of 500). There was a constitution and an assumption of the rule of law presided over by magistrates and juries made up of citizens. More information about Athenian democracy is available at a resourcesforhistoryteachers wikipage on the Government of Ancient Athens.

Greek City-States, Their Governments, and the Demise of Athenian Democracy

Democracy was not the only form of government among the city-states of ancient Greece. In Thebes, and other city-states as well, a small group of land-owning aristocrats (known as the "Oligoi" or the few) governed the community, a form of government called "Oligarchia" (or rule of the few) which has become the modern term oligarchy or rule by a small group (Arnush, 2005). There was also monarchy (rule by one individual who inherited the position by birth) and tyranny (rule by a leader who seized power).

For a short period, Thebes was the leading power in the region, its position maintained in part by the Sacred Band, an elite fighting force made up of pairs of male homosexual lovers who defeated armies from Athens and Sparta between 382 and 335 B.C.E. before the Band was totally defeated by the forces of the Macedonian King Philip II and his son Alexander the Great in 338 B.C.E. Philip became ruler of Greece, effectively ending the era of Athenian democracy. You can learn more from the book The Sacred Band: Three Hundred Theban Lovers Fighting to Save Greek Freedom by James Romm (2021).

In this context of rival city-states and shifting alliances, the emergence of a democratic self-government in Athens - however limited - was a revolutionary development in world history, allowing those who could vote to actively participate in setting policies for the community.

Link to Topic 3.1 ENGAGE in this book to read about current efforts to make Washington, D.C. (District of Columbia) the nation's 51st state and its first city-state.

Special Topic Box: Democracy in the World Today

"Democracy is at risk," declared the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in its 2021 Global State of Democracy Report. "Its survival is endangered by a perfect storm of threats, both from within and from a ride tide of authoritarianism" (p. vii).

Looking at the years 2020 and 2021 and including the impacts of the COVID pandemic, the report assessed the state of democracy in 165 of the world's countries. Only 9% were considered to be high-performing democracies while 70% were non-democratic or democratically backsliding. Backsliding means a gradual, but significant weakening of democratic norms of popular control and political equality. The United States, as well as two other of the world's largest democracies, Brazil and India, have seen significant backsliding in the past years.

While more than half the countries in the world consider themselves democracies, not all are fully democratic (Desilver, 2019). In the modern world, contends one researcher, an "authentic democracy" includes the following structures, without which a democratic system cannot exist:

- "Free, fair, contested, and regularly scheduled elections";

- "Practically all adults have the right to vote and to participate in the electoral process";

- "Minority parties are able to criticize and otherwise oppose the ruling party or parties";

- A constitution "guarantees the rule of law," established limited government, and protects individuals' rights of speech, press, petition, assembly and association. (Patrick, 2006, p.7)

Dartmouth College political scientist Brendan Nyhan (2020) has noted that democracy is not a binary concept; countries are not exclusively democratic or not democratic. Instead, democratic norms are always advancing in some places and eroding in others in response to current events. The organization Freedom House reported that even before the events of the 2020 presidential election and 2021 Insurrection at the Capitol, the United States was experiencing a decline in the index of democracy in the world, occupying a position between Italy and Argentina, well below the most democratic countries: Austria, Chile, Ireland, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain and Uruguay.

In the second decade of the 21st century, democracy and democratic institutions continue to be under assault around the world. The Autocratization Turns Viral: Democracy Report 2021 from the V-Dem Institute at the University of Gottenberg, Sweden notes that although the world is more democratic than it was in the 1970s or 1980s, democracy is on the decline worldwide and the level of democracy experienced by common citizens is at its lowest level since 1990. In many countries (Hungry, India, Cambodia, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey and more), liberal democracy is being replaced by electoral autocracy where political systems have an illusion of multi-party democracy, but free and fair elections do not happen. Instead, strongmen who do not value democratic norms have risen to power.

The Nations in Transit 2020 report from Freedom House reviewed what it calls a "decade of democratic deficits" in which countries experiencing declines in democracy have exceeded countries with gains every year since 2010. In Central Europe, the report notes, there is a growth of "hybrid regimes" in Poland and Hungry where authoritarian leaders have created quasi-autocracies by undermining the independent judiciary, attacking the free press, curtailing civil liberties, and spreading disinformation and propaganda to inflame people's attitudes toward outsiders such as immigrants and asylum-seekers. Despite these developments, the Freedom House report notes, citizen protests against corruption and for environmental protections, particularly in Ukraine and Armenia, represent a significant counterweight to anti-democracy in the region.

Democracy - Our World in Data and Democracy 2019,The Economist magazine’s annual index offer additional perspectives on the place of democracy in the world today.

21st Century Digital Government and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The origins of democracy in ancient Athens invites us to explore how democracy and the democratic government is evolving in today’s digital world and consider how smartphones, computers, and other interactive technologies might create new ways for citizens to interact with political leaders democratically, especially in light of the changes produced by the 2020 pandemic.

"Page of the Town of Amherst Website"

May 2020 during COVID-19 Pandemic

Public Domain

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased efforts by governments to function digitally rather than through face-to-face meetings and interactions. Governments at every level are using mobile apps and social media platforms to communicate information to people about infection rates and appropriate public health practices. At local, state, and national levels, government meetings are being held virtually; in May 2020 the House of Representatives voted to allow remote voting and virtual hearings, ending a 231 year requirement that members be physically present to conduct business. Issuing a policy brief embracing digital government during the pandemic and beyond, the United Nations stated, "Effective public-private partnerships, through sharing technologies, expertise and tools, can support governments in restarting the economy and rebuilding societies" (UN/DESA Policy Brief #61).

Before the pandemic, the northern European country of Estonia claimed to have the world’s first digital government. The first country to declare Internet access as a human right for every person (Estonia is a digital society), 99% of Estonia's government services are online. In 2005, Estonia held the world’s first elections on the Internet; Estonian citizens can now vote online from anywhere in the world. Estonia is also consulting with the government of Ukraine on a “A State in a Smartphone” project where citizens can actively participate in government through electronic petitions, consultations, and elections (Ukrinform, 2020).

"Kersti Kaljulaid MSC 2018" by Mueller is licensed under CC BY 3.0 DE

"Kersti Kaljulaid MSC 2018" by Mueller is licensed under CC BY 3.0 DE

The Estonian President in 2020 is Kersti Kaljulaid, the first woman and youngest person to hold the office. Watch the following videos and consider whether digital technologies and smartphones are a way for more people to participate more fully in democratic government:

In this context, it is possible to consider the issue of how will humans govern outer space? It is projected that there will be regular settlements on the moon, an area about the size of Africa, within the next decade. There are complex issues of exploration and resource ownership and management to be settled.

What will the post-pandemic governments of the future look like? Everyone from elected policymakers to everyday people will be involved in answering this question in the months and years ahead.

Media Literacy Connections: Democracy in Social Media Policies and Community Standards

Athenian democracy's foundational principles included equality, harmony, debate, and general education. Learn how to apply these same principles to more modern-day media by evaluating the community standards, rules, and policies on social media platforms:

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSuggested Learning Activities

- Design an Infographic

- Visit the Philosophies and Forms of Government wiki page

- Choosing between an Oligarchy, Autocracy, Direct Democracy, Representative Democracy, Theocracy or Monarchy, create an infographic describing your selected government, including its benefits and drawbacks.

- Create an interactive Timeline

- Analyze and Discuss

- How might a digital government work in the United States?

- What would be the benefits? What issues might emerge?

- Create a Meme, Editorial Cartoon, or Short Video

- How might students more directly influence decisions and policies if there were a Government with a Smartphone initiative at your school, in your community, and in the state and the United States?

Online Resources for Athenian Democracy and Digital Government

Teacher-Designed Learning Plan: Government in Ancient Athens

Government in Ancient Athens is a learning unit developed by Erich Leaper, 7th-grade teacher at Van Sickle Academy, Springfield Massachusetts, during the spring 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. The unit covers one week of instructional activities and remote learning for students. It addresses both a Massachusetts Grade 7 and a Grade 8 curriculum standard as well as Advanced Placement (AP) Government and Politics unit.

- Massachusetts Grade 7

- Explain the democratic political concepts developed in ancient Greece: a) the "polis" or city state; b) civic participation and voting rights; c) legislative bodies; d) constitution writing; d) rule of law.

- Massachusetts Grade 8

- Explain why the Founders of the United States considered the government of ancient Athens to be the beginning of democracy and explain how the democratic concepts developed in ancient Greece influenced modern democracy.

- Advanced Placement: United States Government and Politics

- Unit 1: Ideas of Democracy

This activity can be adapted and used for in-person, fully online, and blended learning formats.

Athenian Voting is a single-class learning plan that explores the advantages and complexities of direct democracy through a simulation of how decisions were made in ancient Athens.

2. UNCOVER: The Legend of Pheidippides, the Heraean Games and First American Runners in the Boston Marathon and the Olympics

Democracy was not the only accomplishment that modern day America owes to Ancient Greece. Greek thinkers made history-altering contributions in science (Thales), mathematics (Pythagoras and Euclid), medicine (Hippocrates), philosophy (Socrates, Plato and Aristotle), and history, poetry, and drama (Herodotus, Thucydides, Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristophanes and Euripides).

Athletic competitions, signified by the Olympics and its long-distance races, also stretch back to Ancient Greece. The Boston Marathon, the New York City Marathon, and the Olympic Marathon itself are among the most exciting events in sports today. Modern marathons have their origins in ancient Greece with the legend of Pheidippides, a messenger.

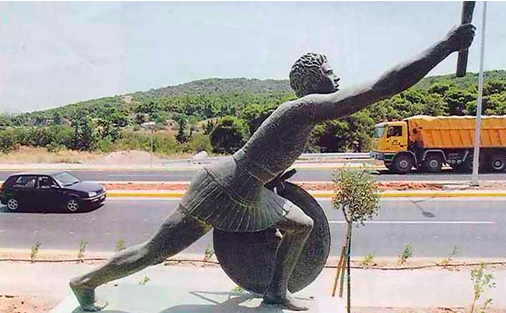

"Statue of Pheidippides along the Marathon Road"

"Statue of Pheidippides along the Marathon Road"

by Hammer of the Gods27 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0During the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, Pheidippides is said to have run from the battlefield of Marathon to Athens to announce a Greek victory, a distance of about 24.85 miles. Pheidippides’ long journey inspired the marathon race at the first modern Olympics in Athens in 1896. Marathons for men have been run in every Olympics since then - a women’s marathon was added in 1984.

The legend of Pheidippides invites exploration of a largely forgotten history of First (or Native) American Runners at the Boston Marathon - the modern world’s oldest annual marathon. Iroquois tribe member Thomas Longboat (or Cogwagee) won the Boston Marathon in 1907 and Ellison "Tarzan" Brown won the race in 1936 and 1939. Google Doodles celebrated Thomas Longboat's 131st birthday with an animation and a short biography on June 4, 2018.

Running is deeply part of American Indian culture and history. It is a spiritual practice for Hopi people. Jim Thorpe (the first Native American to win a gold medal and the greatest multi-sport athlete of the early 20th century), Louis Tewanima (in the 1908 and 1912 Olympics), and Billy Mills (1964 Olympics) also excelled as runners during the Olympics.

Louis Tewanima's story is remarkable, though largely forgotten (Sharp, 2021). As a teenager, he was taken away from his family in Arizona by the U.S. military and enrolled in the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. The school's motto was "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Despite abusive conditions at the school (he could not speak his native language or practice his religion), he became a world-class runner. He finished ninth in the 1908 marathon and won a silver medal in the 10,000 meter event in the 1912 Olympics, setting a U.S. record that would last for 54 years. In his honor and memory, the Louis Tewanima Footrace is held annually at Second Mesa, Arizona. The race was virtual in 2020 during the COVID pandemic.

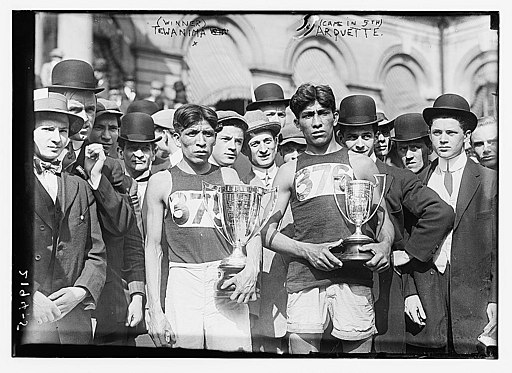

Photo shows Hopi American long distance runner and Olympic medal winner Louis Tewanima (1888-1969) and Mitchell Arquette, member of the cross country team of Carlisle Indian School, after marathon in New York City, May 6, 1911. (Source: Flickr Commons project, 2009 and New York Times, May 7, 1911)

Photo shows Hopi American long distance runner and Olympic medal winner Louis Tewanima (1888-1969) and Mitchell Arquette, member of the cross country team of Carlisle Indian School, after marathon in New York City, May 6, 1911. (Source: Flickr Commons project, 2009 and New York Times, May 7, 1911)The 1912 summer Olympics featured other remarkable performances by Native American athletes, reported Kathleen Sharp in Smithsonian Magazine (2021). Duke Kahanamoku won a gold and silver medal in freestyle swimming events, Jim Thorpe won two gold medals, Andrew Sockalexis finished 4th in the marathon, Benjamin "Joe" Keeper placed 4th in the 10,000 meter race, and Alexander Wuttunee-Decoteau took 6th place in the 5,000 meter competition. You can learn more about running and sports among First Americans from the article “For Young Native Americans, Running is a Lesson in their own History.”

In addition to the marathon, athletic competition in ancient Greece featured tests of individual skill and strength for men - there were no team sports or records kept of individual achievements. The first Olympic Games were held in 776 BCE. Events included sprinting, wrestling, javelin, discus, chariot racing, and a fight to the death called "pankration." The ancient Olympics were abolished by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I in 393 or 394 CE (Frequently Asked Questions about the Olympic Games).

Women were excluded from Olympic events with men. Unmarried girls were allowed to participate in their own athletic event - a once-every-four-years foot race during the Festival of Hera known as the Heraean Games. The first woman to win a male Olympic event was Cynisca from Sparta who won the four-horse chariot race twice, in 396 and 392 BCE. Monuments were built to honor her achievements. The modern Olympics began in 1896 and women were allowed to participate for the first time in 1900. In 2016, women were 45% of Olympic competitors (5,176 out of 11,444 athletes (Key Dates in the History of Women in the Olympic Movement). Nearly half (49%) of the athletes participating in the 2020 Tokyo Games were women.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Use the following resources for a student-made TV news and sports show discussing how running and other sports have evolved in American Indian communities:

- Sports were Essential to the Life of the Early North American Indian, Sports Illustrated, December 1,1986

- Legend of Tarzan: Stories about Brown Have Legs, The Boston Globe, April 13, 2016

- Tradition of Champion Native Runners in Boston Continues, Indian Country Today (March 8, 2017)

- The Importance of Running in Native American Culture, Women's Running (February 25, 2019)

- For Young Native Americans, Running Is a Lesson in Their Own History, The Christian Science Monitor (January 15, 2019)

Online Resources for the History of the Marathon

Teacher-Designed Learning Plan: The Ancient and Modern Olympics

The Ancient and Modern Olympics is a learning activity developed by social studies teacher Erich Leaper and University of Massachusetts Amherst faculty member Robert Maloy. It is designed for in person, virtual or hybrid learning settings and addresses the following curriculum standard:

- Massachusetts Grade 7: Topic 4/Standard 7

- Identify the major accomplishments of the ancient Greeks

3. ENGAGE: How Can Teachers and Students Collaborate to Build More Democratic Classrooms?

“Although we think of ourselves as living in a democratic society," observed journalist Jay Cassano (2015), "we actually practice democracy very rarely in our everyday lives" (para. 1).

Many consider voting for President every four years as their primary democratic experience, but practicing democracy also means exercising one’s rights through free speech, peaceful protests, petitions for change, consumer boycotts and buycotts, and other forms of civic participation and engagement. Democracy also means having a say in determining what happens in one's work, family, education and recreation settings. It is through vote and voice, people have opportunities to exercise control and agency over their lives.

Worker cooperatives and worker/employee owned businesses are increasing in our economy, but are not widely discussed as examples of democracy being practiced in American society. Cooperatives (aka co-ops) are organizations where “the people who own the businesses are the same people who work there” (Anzilotti, 2017, para. 4). You can learn more about worker cooperatives and workplace democracy in Topic 6/Standard 10 in this book.

Democratic Schools and School Democracy

Democratic schools have classrooms where students invest time and energy in designing their educational activities. Advocates believe schools should organize educational experiences so that both students and teachers have voice and vote about what happens instructionally and interpersonally in classrooms and corridors.

In democratic classroom environments, students are involved “on a regular basis and in developmentally appropriate ways, in sharing decision making that increases their responsibility for helping to make the classroom a good place to be and learn” (A Democratic Classroom Environment, State University of New York Cortland, para. 1).

Democratic schools, contend Michael Apple and James Beane (2007), involve two essential elements:

- “Democratic structures and processes by which life in the school is carried out and

- A curriculum that gives young people democratic experiences” (pp. 9-10).

Despite the civic learning opportunities presented by democratic schools, teacher/student conversations in many classrooms, even those claiming to be democratic, tend to follow an "initiation-response-evaluation" pattern where teachers ask questions, students respond, and teachers assess the rightness of the responses (Thornberg, 2010). Such interactions lack the open back and forth conversational exchanges of real democratic talk, putting off students or leaving them openly cynical about the idea of democracy in schools or the larger society.

In related study, Swedish researchers Robert Thornberg and Helene Elvstrand (2012) examined children's experiences with democracy, participation, and trust in how teachers and students established school rules. They found, even in the school that had student voice and participation as an explicit educational goal, children's "position is subordinated, their voice is often suppressed, and the value of their voice is minimized." They urged teachers to recognize how taken-for-granted, adult-centered interactions can and do counteract efforts to build school democracy.

How would you make school classrooms and school organizations more democratic spaces for students?

Having student representatives on local school boards or other educational decision-making committees is one idea for students having democratic experiences in schools. Many districts allow students to have an advisory role on school boards and committees, but actual student voting power is fairly rare. In Maryland, however, students do vote on many school boards in the state, although not on the hiring of school personnel. In the state's Montgomery County, high school students choose their school board student representative through direct election.

Allowing students to vote on local school boards is complicated, and in some places, a contentious issue. In late 2020, a group of Maryland parents filed a lawsuit against the practice after a student representative cast the deciding vote to block a return to in-person schooling during the pandemic. The parents claimed student member voting rights violated the Maryland state Constitution that sets the legal voting age in the state at 18. The student representative said he hoped the lawsuit would be unsuccessful because students need to have a consequential voice in educational matters that directly affect them (Baltimore Sun, December 18, 2020).

Suggested Learning Activities

- Watch and Learn

- Watch teachers, including Marco Torres, describe what it is like to teach democratically in school classrooms from the Democratic Classrooms page of Teaching Tolerance.

- Dialogue and Debate

- How can students create more democratic schools and classrooms?

- How can students gain greater voice and agency in school classrooms and learning activities?

- Would you involve students in setting school rules and codes of conduct?

- Would you invite students to help shape daily teaching and learning experiences, including deciding what curriculum topics to explore and what instructional methods for teachers to include in daily activities?

- Do you agree or disagree with suggestions for democratic classrooms offered in What is Democratic Education?

- Draw Connections to Personal Experiences

- How do you define democracy?

- What are your earliest memories of participating in a democratic setting? When you were in a situation where you felt your voice and participation mattered to making decisions?

- Was it in a family setting, at church, during youth sports, with peers, in stage or musical performances?

- When were you listened to and when were you not listened to?

- What role did you play in the process?

- Conduct a Poll

- Ask 5 other people for their earliest memories of participating in a democratic setting. List times when those interviewed felt their voice and participation mattered and when it did not matter.

- You can ask your: Family, community, peers, and school members.

Online Resources for Democratic Schools

Standard 1.1 Conclusion

The United States system of government has its origins in the Greek city-state of ancient Athens. INVESTIGATE examined the nature and decidedly undemocratic elements of Athenian democracy, particularly in terms of women’s roles, before considering how today's interactive digital technologies may offer new ways for people to participate directly in government and decision-making. UNCOVER looked at Greek marathons and the histories of First (Native) American runners in the Boston Marathon and Olympic competitions. ENGAGE asked how school classrooms can become more democratic spaces where students have greater voice and agency concerning their educational learning activities.