Standard 4.1: Becoming a Citizen

Explain the different ways one becomes a citizen of the United States. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T4.1]

FOCUS QUESTION: How has the Meaning of Citizenship in the United States Changed Over Time?

"The Citizen's Almanac" by USCIS | Public Domain

"The Citizen's Almanac" by USCIS | Public Domain"America is a nation peopled by the world, and we are all Americans," wrote historian Ronald Takaki at the beginning of A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America (2008, p. 5).

His book brought together the multiple histories of citizenship, immigration, and America's multicultural society while challenging a longstanding “master narrative of American history” that has marginalized the experiences of indigenous people as well as those who came here (voluntarily and by force) from Africa, Asia, and Latin America (2008, p. 5). For Takaki, it is important to view society through a different mirror that enables us to learn the how and why of America, its history, and our country’s “amazingly unique society of varied races, ethnicities, and religions” (2008, p. 20).

Who then were the first citizens of America?

First American tribes lived in North America for 50,000 years before the arrival of Europeans. It is estimated that between 1492 and 1600, 90% of the native population died from diseases (smallpox, influenza, measles, chicken pox) introduced by European settlers (The Story of . . .Smallpox --and other Deadly Eurasian Germs, PBS, 2005).

From the outset of European settlement, North America was a multiculturally diverse continent. Before the American Revolution, there were Spanish settlers in Florida, British in New England and Virginia, Dutch in New York, and Swedish in Delaware.

There were slaves - 10.7 million Africans brought to the New World - none of whom “immigrated” to this country under their own free will (Gates, Jr. | PBS). There were also indentured servants in the colonies as well as 50,000 convicts sent from jails in England.

The first Census in 1790 listed 3.9 million people living in the country - Native Americans were not counted. Nearly 20% of the people were of African heritage (but slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person).

At the time of the Civil War, the nation’s population was nearly 31.5 million people - 23 million in the northern states including 476,000 free Blacks and 9 million the southern states, of whom 3.5 million were enslaved Africans (North and South in 1861, North Carolina History Online). Follow the rest of the story at Immigration Timeline, a site from the Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island Foundation.

Throughout American history, immigrants from many different countries and faiths have struggled to obtain citizenship under the nation’s changing laws and policies. The United States, observed historian David Nasaw (2020), "is and has always been both a nation of immigrants and a nation that periodically wages war against them" (para. 1).

Even "birthright citizenship," the principle that anyone born in the country is automatically a citizen was initially just for “free white persons.” It has taken time, protests, and the Civil War to expand the boundaries of who could become an American citizen. Blacks were not granted citizenship until the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868. It took a Supreme Court decision, United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1895), to overthrow the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and establish birthright citizenship for Chinese Americans. American Indians did not gain full citizenship until 1924.

The modules for this standard explore the diverse histories of people becoming citizens of the United States, including the official rules and procedures for how someone becomes a United States citizen as well as less often discussed citizenship histories of indigenous peoples, Africans who came to America involuntarily as slaves, and immigrants who came here voluntarily. There is also a module focusing on the complicated story of Puerto Rican citizenship and a module exploring when someone should be granted asylum in the United States.

1. INVESTIGATE: Becoming a Citizen Through Immigration Gateways and Ports of Entry

Broadly defined, Citizenship consists of enjoying the benefits and assuming the responsibilities of membership in a shared community. Legally, the two most important tools traditionally used to determine citizenship are:

- Birthplace, or jus soli, being born in a territory over which the state maintains, has maintained, or wishes to extend its sovereignty.

- Bloodline, or jus sanguinis, citizenship as a result of the nationality of one parent or of other, more distant ancestors. Hansen and Weil (2002, p. 2)

All nations use birthplace and bloodlines in defining attribution of citizenship at birth. However, two other tools are used in citizenship law, attributing citizenship after birth through naturalization:

- Marital status, in that marriage to a citizen of another country can lead to the acquisition of the spouse's citizenship.

- Residence, past, present, or future within the country's past, present, future, or intended borders (including colonial borders)

Special Topic Box: How to Become a United States Citizen

According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (para. 1):

To become a citizen at birth, you must:

- Have been born in the United States or certain territories or outlying possessions of the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States; OR

- had a parent or parents who were citizens at the time of your birth (if you were born abroad) and meet other requirements

To become a citizen after birth, you must:

The Citizenship Test

The outgoing Trump Administration has made changes to the citizenship test, making it longer and more difficult. The test bank has been expanded to 128 questions, up from 100 questions and a passing score is now 12 out of 20 questions correct (US Citizenship Test is Longer and More Difficult, The New York Times, December 3, 2020).

There seem to be clear biases in the way questions are asked. One of the questions asked "Whom does a senator represent?" The correct answer according to the test writers is the citizens of a state, not all the people of a state, a phrasing that dismisses the status of immigrants and undocumented people.

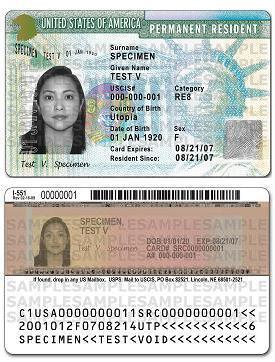

Green Card Status

The U.S. also grants green card status to immigrants, which allow them to live and work in the country on a permanent basis (for more information, go to Get a Green Card). After 3 to 5 years and if other criteria are met, green card holders can apply for citizenship (for more information, go to I Am a Permanent Resident. How do I Apply for U.S. Citizenship).

US Permanent Resident Card by USCIS | Public Domain

US Permanent Resident Card by USCIS | Public DomainCosts

Becoming a citizen also costs money. Currently there is a $725 per person non-refundable application fee, a great burden for those living paycheck to paycheck; the fee in 1985 was $35. It is estimated that some 9 million people who could become full citizens have not done so, in part because they do not have enough money to avoid the fee ("The Land of the Fee," Boston Sunday Globe Metro, May 30, 2021, p. B1, para. 6-7).

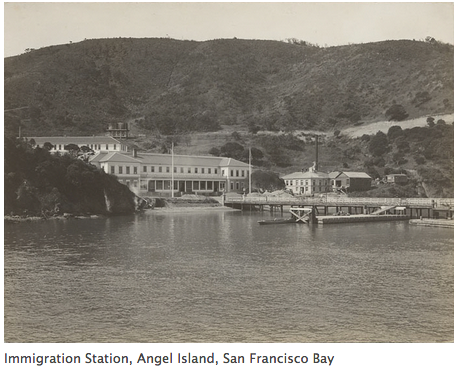

"Angel Island Immigration Station" by Hart Hyatt | Public Domain

"Angel Island Immigration Station" by Hart Hyatt | Public DomainImmigration Gateways, Ports of Entry, and Citizenship Histories

United States citizenship, however, is more than a set of legal principles that are applied in a court of law; citizenship is the product of historical developments and changing policies toward migrants and newcomers.

From colonial times, those who came here from other places entered the United States through one of the following Immigration Gateways or Ports of Entry, many of which were islands:

- Castle Island

- Ellis Island

- Sullivan's Island

- Angel Island

- Pelican Island

- U.S./Mexico Border

The citizenship histories of diverse Americans can be accessed at the following resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki pages:

Not everyone who entered the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries automatically became a citizen (Museum at Eldridge Street, New York, NY). Following the passage of the Naturalization Act of 1906, immigrants had to file a petition for citizenship, be able to speak English, reside in the country for between 2 and 7 years, and have a hearing before a judge that usually involved answering questions orally about U.S. history and government (Background History of the United States Naturalization Process). Passing a spoken test became a formal requirement for citizenship in 1950.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Design an Interactive Visual Story

- Analyze the Life Stories of Immigrants

- Explore immigrant stories available from:

- Analyze a Primary Source

- Read aloud The New Colossus by Emma Lazarus, the poem found at the Statue of Liberty in New York City Harbor.

- What did the poet mean through her use of phrases such as “glows world-wide welcome,” “huddled masses,” “tempest-toss,” and “golden door?”

- State Your View

- Should all high school students have to pass the U.S. Citizenship test to graduate?

Online Resources for Becoming a Citizen

2. UNCOVER: Citizenship for Puerto Ricans

Applying Takaki's different mirror point of view, citizenship histories of Puerto Ricans reveals longstanding patterns of discrimination and indifference toward the island and its peoples.

"2009 Puerto Rico Quarter" | Public Domain

"2009 Puerto Rico Quarter" | Public Domain3.4 million people currently live on the island of Puerto Rico. Another 5.1 million Puerto Ricans reside in other parts of the United States. They are the second largest Hispanic sub-group, accounting for 9.5% of the nation’s Hispanic population (Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Statistical Portrait, Pew Hispanic Center, March 25, 2019).

Puerto Rico became a United States territory after the Spanish-American War in 1898. The Jones-Shafroth Act (1917) granted U.S. citizenship to anyone born on the island; the island’s 1954 Constitution established its status as a commonwealth or estado libre asociado (free associated state).

Puerto Rico's government functions much like other U.S. state governments. People vote for the governor, members of the legislature, and the island's representative to the House of Representatives - known as a Resident Commissioner (although that person does not have a vote in the House). However, Puerto Ricans cannot vote in U.S. Presidential elections.

For more information, view the video Why Puerto Rico is not a US State (Vox, January 25, 2018). Review the debate over statehood for Puerto Rico here.

Puerto Ricans have impacted every part of American life and culture. The 65th Infantry Regiment or Borinqueneers (the original Taino Indian name for Puerto Rico) was the first group of Hispanic segregated soldiers in U.S. history—they fought in World War I & II, Korea, and Vietnam and received a Congressional Gold Medal in 2016. Sonia Sotomayor, whose parents are Puerto Rican, is a current Supreme Court Justice. Deborah Aguiar-Velez is the author of Spanish language computer science textbooks. Rita Moreno won all four major entertainment awards: the Oscar, Tony, Emmy, and Grammy. Roberto Clemente was the first Latin American Hall of Fame baseball player and humanitarian. The list goes on and on.

Roberto Clemente at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, PA

Roberto Clemente at PNC Park in Pittsburgh, PA

"Roberto Clemente statue" | Public DomainPuerto Rico currently faces enormous social and economic problems. The Census Bureau reports that 46.1% of the people live below the poverty line. Unemployment is more than double the national average. Food insecurity is four times that of average Americans. The 2016 Zika virus created an island-wide health crisis. Hurricanes Irma and Maria devastated large areas, destroying infrastructure and dislocating people. Aid has been slow to respond. In a 2019 political crisis, corruption was revealed, leading to the resignation of the island’s governor following 12 days of massive citizen protests—the first time a governor had to leave office without an election. Puerto Rico: History and Government offers more information about the island and its relationship with the United States.

Suggested Learning Activities

- State Your View

- What steps does the United States need to take to provide aid and support for the people who live in Puerto Rico?

- Make a Digital Poster

- Research and create an online biography poster for a Puerto Rican woman or man who has made extensive contributions in math, science, the arts or politics; for example Sonia Sotomayor, Jennifer Lopez, Rita Moreno, Lin-Manuel Miranda, and another Puerto Rican change maker.

- Here is a page example for Roberto Clemente, Baseball Player, Humanitarian and Activist.

Online Resources for Puerto Rican history

- New England's Forgotten Puerto Rican Riots, New England Historical Society

- Puerto Rican Children's Literature for Social Justice: A Bibliography for Educators, Social Justice Books

- The Law that Made Puerto Ricans U.S. Citizens, Yet Not Fully Americans, Zocalo Public Square (March 8, 2018)

- After a Century of American Citizenship, Puerto Ricans Have Little to Show for It, The Nation (March 2, 2017)

- Through a Puerto Rican Lens: The Legacy of the Jones Act, National Museum of American History

- Puerto Rico Citizenship Archives Project, University of Connecticut

3. ENGAGE: When Should Someone Be Granted Asylum in the United States?

There were no federal immigration restrictions in the U.S. until the Page Act of 1875 (directed at barring female prostitutes from entering the country, it effectively prevented all Chinese women from immigrating to the U.S.) and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Between 1900 and 1920, some 24 million immigrants came to the United States, mostly from European countries. To control the flow after World War I, Congress passed national-origins quotas in 1921 and again in 1924. Immigration numbers dropped during the Great Depression and the U.S. sought to import laborers from Mexico through the Bracero Program.

"Mexicali Braceros, 1954" by Los Angeles Times | Public Domain

"Mexicali Braceros, 1954" by Los Angeles Times | Public DomainDuring the 1930s and 1940s, the United States refused asylum for large numbers of Jewish refugees who were fleeing the Holocaust in Nazi Germany (America and the Holocaust, Facing History and Ourselves). By the 1960s, immigrants increasingly came from Asia and Latin America. Initially, Congress allowed immigration numbers to rise, but after the 2001 September 11 Attacks, public opinion shifted against people coming to the United States.

"Man Woman Children" by Kalhh | Public Domain

"Man Woman Children" by Kalhh | Public DomainAsylum means protection or safety from harm. It is granted by a government to someone who is a refugee and cannot safely return to their home country (see Asylum in the United States by the American Immigration Council).

Thousands of people every year seek asylum in the United States. The U. S. government must consider those asylum requests under the provisions of the Refugee Act of 1980. The United States granted asylum to, on average, 25,161 individuals every year between 2007 and 2018 (Fact Sheet for Asylum in the United States).

Under current U.S. and international law, anyone who physically steps on United States soil is entitled to apply for asylum. Asylum seekers must then pass a "credible fear" interview with Immigration Agents who determine if the person(s) faces "significant possibility of persecution or harm” in their home country. An immigration court makes the final decision as to asylum. In 2018, 89% passed initial screening, however, under revised Trump Administration rules, only 17% were granted asylum in 2019 (The Complicated History of Asylum in America-Explained).

Asylum for refugees became a highly contested political topic in 2019. In response to the arrival of migrants at the U.S./Mexico border, the Trump Administration took steps to tighten restrictions on who could enter the country by requiring migrants to first seek asylum in a Central American country before applying for that status in the United States. In 2020, President Trump used the global COVID-19 pandemic as an reason to block migrants and asylum seekers at US-Mexico border.

Media Literacy Connections: Immigration in the News

The United States now has more immigrants than any other country in the world, reports the Pew Research Center - some 40 million people or about 14% of the nation's total population. But immigration is a complex and contentious political issue. Read Why Is Immigration Such a Hot-Button Issue? from the St. Mary's College Newsletter to get a sense of the wide range of viewpoints about immigration. Some commentators want to provide more opportunities for immigration; others want to restrict immigration even more drastically.

Focusing on news and current events, this activity asks you to compare and contrast different media treatments of immigration and present your findings to a school or local newspaper.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

Suggested Learning Activities

- Record a Digital Story

- Use written words, audio narration, and images to tell the story of refugees seeking asylum in the United States

- Refugees/Asylum Lesson Plan, Immigration History

- State Your View

- Who should be granted asylum in the United States?

- When, and for what reason, should someone be granted asylum in the United States?

Online Resources for Asylum

Standard 4.1 Conclusion

In exploring this standard, INVESTIGATE examined how immigration is connected to citizenship, first in terms of the laws pertaining to citizenship and then by identifying the ports of entry and immigration gateways where people have historically entered the United States: Castle Island, Ellis Island, Sullivan’s Island, Angel Island, Pelican Island, and the U.S./Mexican border. UNCOVER presented the history and consequences of citizenship for the people of Puerto Rico. ENGAGE asked students to consider when someone should be granted asylum in the United States.