This design case documents how a K-12 district took steps to systemically support virtual student wellness and belonging. Plans for course design to support social-emotional-academic learning (SEAL) competencies, increase perception of belonging, and create safe, predictable learning environments characteristic of a trauma-informed approach to teaching and learning are shared. The assumption virtual learners are not looking to experience belonging and cannot be successful unless they already have strong SEAL skills is challenged. Rather, the positioning of SEAL competencies as learning objectives rather than necessary prerequisites to access online learning proved to contribute to more equitable learning opportunities.

Background

An effective approach to trauma-informed, social-emotional-academic learning (SEAL) includes providing space for students to develop and practice key SEAL competencies–such as those related to self-awareness and self-regulation–while building and maintaining strong and supportive relationships in the classroom and across the school (Frydman & Mayor, 2017). As part of a larger trauma-informed SEAL framework, this approach contributes to the creation of safe, predictable learning environments where students are empowered and supported to manage the adverse effects of trauma while adults’ awareness and sensitivity help avoid the perpetuation of trauma throughout the school day (Frydman & Mayor, 2017; Ngo et al., 2008). For learning pathways that occur in online environments, too often some demonstration of a cited level of attainment of these SEAL competencies is required, gatekeeping students deemed “not ready” from online learning pathways. Moore (2021a) reframes this relationship, suggesting when SEAL competencies are positioned as learning objectives rather than necessary prerequisites, access to more equitable learning opportunities become available to all students.

This design case highlights how Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding allowed a K-12 public school district in southeastern PA prioritize two initiatives as students returned from emergency remote modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic: growth of online learning pathways and opportunities for SEAL competency development. While these roles are traditionally siloed in K-12 organizational structures (Smith et al., 2020), the intentional collaboration and critical co-reflection between the two coordinators of these initiatives led to the implementation of programming designed to address a root issue sometimes overlooked in trauma-informed education: societal inequity (Venet, 2021).

Four specific design considerations inspired by Whitbeck’s (1996) conceptualization of ethics as design, are described: (1) embracing uncertainty despite the use of external representations, (2) iteration of design elements and implementation over the course of the academic calendar year, (3) the development of feedback loops from all invested participants, and (4) the need to balance fidelity with flexibility in the creation of a resilient system. Designer reflections are also shared as a critical part of the intentional documented record of design practice (see Boling, 2010).

Documenting design cases allows for a rich explanation of design practice in authentic environments (Smith, 2010). While not intended to be generalizable, design cases present practical application precedent (Gray & Boling, 2016) and make explicit ways in which core values influence design decisions (Gray et al., 2015). The focus of this design case is on how centering equity as a core design value drove the development, implementation, and planned evaluation of opportunities for SEAL competency development over the course of a calendar year within the district’s 100% asynchronous virtual learning environment.

Design Positionality

Our design team consisted of two Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funded individuals: our Online and Digital Learning Coordinator (first author) and our Social, Emotional, and Academic Learning Coordinator (second author). ESSER funds were awarded by the US Department of Education to a variety of educational agencies to address the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on various educational programming (Office of Elementary and Secondary Education [OESE], 2022). The nature of funding is relevant here as ESSER funds stipulate schools have three years in which to use the funding, throughout which documented steps need to be provided on how district initiatives are being made endemic to existing systems. Using this revenue stream for positions provides an interesting perspective to district initiative planning–anything we built needed to be fully developed at the end of three years and sustainable, possibly without continued direction from the individuals responsible for design.

Design Context

Centennial School District (CSD)

Centennial School District (CSD) is a suburban Philadelphia K-12 school district of approximately 5500 diverse learners. In our district, 39 different languages and 43 countries are represented. Forty-nine percent of our student population qualifies for free and reduced lunch. Notably, in the return to in-person learning for the 2021-2022 school year, 130 CSD students chose to remain in a virtual placement, necessitating the creation of the Centennial Virtual Learning Academy (CVLA), a fully asynchronous online learning pathway. Hanover Research (2019) consistently advocates for red flags for trauma to be handled via consultation with certified mental health professionals. Importantly, CSD has expanded their counseling team to include two certified mental health counselors. What is shared here was designed intentionally for Tier 1 intervention.

Online and Digital Learning

As we move to an increasingly endemic phase of the pandemic, approximately 60 students, Grades K-12, have chosen to remain completely virtual for the 2022-2023 school year. Additionally, in response to growing demands for students who want virtual opportunities without being siloed into a completely virtual pathway, a blended schedule pilot for Grade 12 students only was offered this year. Seniors can take up to four credits virtually, with the remainder of their required credits being offered via traditional face-to-face modalities. Fifteen students have chosen to take part in this blended learning pathway.

Also new for the 2022-2023 school year, CSD teachers are responsible for the facilitation of courses for our Grade 12 students, both those involved in our blended schedule pilot and those remaining in a 100% virtual pathway. This shift has allowed us to use our own learning management system (LMS), Canvas, for course delivery. Curriculum continues to be provided by a third-party partner but is aligned to district standards and level of rigor.

Social Emotional Academic Learning

In creating a position specifically dedicated to social-emotional learning, district leadership was deliberate in adding an “A” to what is traditionally known as “SEL,” creating the initiative title “Social, Emotional, and Academic Learning” or, “SEAL.” Conceptually, this addition was to position social, emotional, and academic skill development as all being equally important, reflecting research outcomes showing the academic benefits for students who participate in evidence-based social-emotional programming (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning [CASEL], 2022). In practice, this title set the trajectory within the district for prioritizing classroom practices that integrate social-emotional learning into academic content instruction.

Upon starting the new position with CSD, the SEAL Coordinator conducted a front-end needs analysis (FEA; see Harless, 1970) of past and current SEAL implementation and practice within CSD. The results of this FEA directed the SEAL Coordinator to first ensure a common mission and vision for SEAL implementation district-wide with both central and building administration teams. Prioritizing a distributive leadership model, a district SEAL team, including seven building-level faculty liaisons, was convened. Together, these individuals conducted stakeholder surveys, a climate and culture survey, and a review of discipline referral data. Triangulation of this data identified implementation and outcome goals aligned to four identified district priority areas: creating and maintaining a supportive climate and culture; systematic social, emotional, and academic skill development; fostering adult social and emotional wellness; and family engagement and partnerships. An implementation rubric and ongoing climate and culture survey tools will determine progress toward goals.

Perspective from our Silos

For the 2021-22 school year, both the Online and Digital Learning coordinator and SEAL coordinator worked within the vertical structures of their respective departments–online and digital learning was housed in the Office of Teaching and Learning and SEAL was housed in Student Services–to establish goals and frameworks for implementation. This intradepartmental focus, while necessary to some extent, can create initiative silos defined by myopic focus on departmental goals (Smith et al., 2020). In our case, continued development within our individual silos as we entered year two of our tenure, would have perpetuated inequities wherein students in the brick-and-mortar setting would be given access to opportunities for SEAL skill development and belonging, while those in the CVLA program would not. CSD’s mission, vision, beliefs, and values (see CSD, 2022) set the intention to support and prepare all students for post-secondary college, career, and life-readiness and as such, the coordinators chose intentional collaboration as a way to integrate the initiatives.

Intentional Collaboration

In-Person SEAL Action Steps

Beginning in the 2022-23 school year, the elementary and middle schools evaluated and refined their approaches to schoolwide positive behavior supports. In-person elementary students began to participate in a daily Morning Meeting and in-person middle school students participated in regular SEAL activities during a new “What I Need” time. The high school established a schoolwide focus on building positive relationships along with clear shared expectations. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning’s (CASEL) (2022) Three Signature Practices are being phased into classes K-12 and used by administrators when leading meetings. District leaders are collaborating to integrate SEAL into existing systems; for example, staff are encouraged to choose a SEAL focus for their evaluation pathway.

Design Opportunity- Virtual SEAL Action Steps

In planning for the 2022-2023 academic school year, a design opportunity became apparent: how could we provide opportunities for SEAL competency development to virtual learners via inherent design elements of our new in-house virtual learning pathway? Moore (2021a) alludes to the idea that online learners, by nature of their chosen learning pathways, are often assumed to already be proficient in various SEAL competencies. Furthermore, the growing body of research on K-12 SEAL competency development (Brackett et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2014) focuses primarily on in-person learning. Assuming or unintentionally excluding a growing population of online K-12 learners from developing these career-ready skills (Pennsylvania Department of Education [PDE], 2022), creates both an inequitable learning environment (Tawfik et al., 2021) and may lead to diminished future opportunities for students who have elected or had circumstances elect this learning pathway. The need for virtual learners to have equitable opportunities to develop SEAL competencies became our design opportunity.

Conceptual Framework- A Trauma-Informed Systems Approach

Smith (2010) suggests a priori theoretical and conceptual frameworks may not actually be appropriate for design cases which are useful to the field simply because they establish design precedent in real-world contexts. However, within the real-world context of a school system, policy often drives the need for design. True et al.’s (2007) punctuated equilibrium model suggests that policy change is incremental and arises when new understandings, theories, or ways of thinking about policy problems come to light. As such, sharing theory that shaped the policy driving the need for this design case is relevant.

Venet’s (2021) conceptualization of trauma-informed education suggests a focus on the educational ecosystem instead of the individual classroom or, worse, a need to “fix” the individual student. District policy, school climate, and classroom practice should all be aligned to provide a trauma-informed environment (Venet, 2021) as opposed to individual trauma-informed experiences amidst a system that may unconsciously continue to perpetuate inequities.

Within the unique system of a K-12 school district, school boards are responsible for setting policy; school administrators (such as ourselves) are responsible for development of procedures to carry out set policy. In Fall 2021, the CSD school board adopted a policy to direct district staff to develop and implement a trauma-informed approach to education, with special attention called to reviewing procedures on attendance, opportunities for relationship building, and opportunities for curriculum and instruction development with embedded social emotional learning. Inherent in this policy is the district’s conceptualization of a trauma-informed practice which seeks to recognize trauma, respond without retraumatizing, and build both individual and systemic resilience (CSD, 2021). Moore (2022) suggests a reconceptualization of resiliency as the ability of systems to be flexible in varying situations. This reminder that resiliency is a systems issue, as opposed to a trait we seek to develop in individuals, allowed for an important reframing of our design opportunity (see Svhila, 2020). Instead of suggesting students’ trauma was a problem that needed fixing, or positioning ourselves (and training faculty) as fixers of trauma, we sought to develop a system that would not perpetuate traumas and could allow students flexibility while still helping to develop college and career readiness-related skills. Restorative practices, culturally responsive practices, and embedded SEAL opportunities are all mentioned within the policy as tools for reviewing current district practice and implementing a more trauma-informed approach; however specific implementation recommendations are not defined.

Embedding a trauma-informed practice into the domains of SEAL is common practice for public school systems across the nation (Thomas et al., 2019), which have not, by and large, adopted formal frameworks or even common definitions of “trauma-informed approach” (Hanson & Lang, 2016; Maynard et al., 2019). Furthermore, some educational leaders have suggested a focus on trauma-informed practices is distracting from the need to engage in larger-scaled equity work within public school systems (Venet, 2021). In Spring 2022, CSD also adopted an educational equity policy, with the directive that CSD students should be provided with not just equitable access to educational opportunities but also that CSD staff should develop and implement programming to best ensure equitable student success.

With district policy in place, but perhaps a lack of an operational implementation plan for a trauma-informed approach, we made the decision to center equity as the core design value (see Gray & Boling, 2016) in a system redesign intended to provide opportunities for SEAL competency development for virtual learners throughout the scholastic year. Centering equity as a core design value to our growing conceptualization of a trauma-informed approach led to the realization of a need to build a resilient system that would be flexible enough to adapt to individual needs.

Design Process

With our design opportunity reframed, the Online and Digital Learning Coordinator and SEAL Coordinator scheduled dedicated weekly meetings to this design project. These meetings gave us time to share perspectives from our individual silos to understand district needs beyond what might be obvious to us in our specialty areas. As overlaps emerged, this collaborative time also allowed us the opportunity to design a series of interventions that could provide opportunities for SEAL competency development among our virtual learner population.

Infusing equity throughout the design process required our team to look outside of traditional instructional design models for our process (see Moore, 2021b). Our team had concerns that traditional prescriptive design models (see Dick et al., 2005; Gagné et al., 2005, Morrison et al., 2013), which make little to no mention of the importance of societal context and the responsibility of design to promote equity, would fail to honor our commitment to our core design value. Whitbeck’s (1996) approach to ethics as design, while not an instructional design model, provided us with four broad considerations guiding constant reanalysis of systemic constraints at multiple points of our iterative design process. These considerations encouraged us to: (1) embrace uncertainty, (2) iterate, (3) develop ongoing feedback loops, and (4) balance flexibility with fidelity to our core design value. As equity is both an ethical issue as well as a design problem (Moore 2021b), reframing Whitbeck’s considerations as our “design model” provided a loose framework to focus on building resilience in our systems as opposed to requiring it of our individuals.

Consider: Embracing Uncertainty

While designers go through multiple processes to help resolve uncertainties that surround design opportunities (Stefaniak et al., 2022; Tracey & Hutchinson, 2018), Whitbeck (1996) suggests waiting to act until one is certain is a “license to avoid action” (p.13). Strategies such as reflection-in-action can help designers mitigate uncertainty (Tracey & Hutchinson, 2018) and continue moving through the design process.

One of the major sources of uncertainty surrounding our design opportunity was selecting the correct localized context of use (see Baaki & Tracey, 2019; Herman et al., 2022) within our system. Our objective was to create opportunities for students to practice SEAL development– but who would support these opportunities? Should students need to self-regulate and reflect–two skills we were hoping to develop but not require as prerequisites? Should faculty need to collect and analyze data on student progress on top of navigating content dissemination and course facilitation in a new modality? Could we embed opportunities for SEAL competency development directly in the virtual curriculum or course design?

The use of external representations as a part of reflective practice can help resolve uncertainty (Baaki et al., 2017; Stefaniak et al., 2022). Vision concepts and other forms of external representations are already familiar tools to the instructional design field, particularly those utilizing a dynamic decision-making approach (see Stefaniak et al., 2021). External representations can assist the design team to engage in reflection in action while undergoing a fluid design process, capturing their (perhaps varied) interpretations of how the design is progressing (Stefaniak et al., 2021). Capturing iterations of the design process on paper (or via models) allows for dialogue between the design team and the design, and gives the design itself a seat at the table.

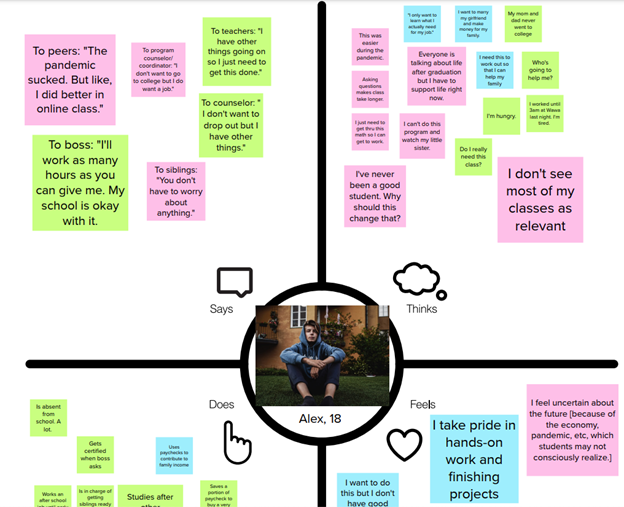

In communicating the need for ongoing virtual programming to our school board and community, a persona of a virtual learner from the Centennial School District had been developed (see Figure 1). This persona suggested a typical virtual student who was juggling school, work, and home responsibilities and needed the flexibility of time and place inherently available in online learning.

Figure 1

Virtual Learner Persona

An empathy map shows a teenage boy named Alex in the center. Surrounding him are words he says, thoughts he has, actions he takes, and feelings he has around his education.

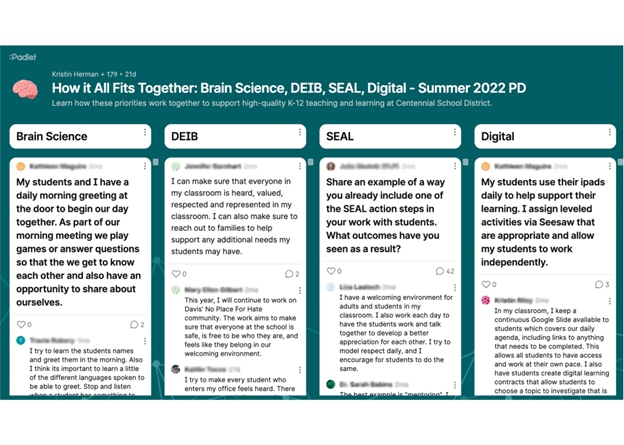

An empathy map shows a teenage boy named Alex in the center. Surrounding him are words he says, thoughts he has, actions he takes, and feelings he has around his education.A discussion board for faculty in response to a summer professional development on how the district envisioned the intersection between equity, SEAL, and digital learning (see Figure 2), provided a second external representation. This artifact allowed us to reflect on where faculty were with district initiative implementation, examined on Freire’s (1970/2000) name-reflect-act continuum of critical consciousness.

Figure 2

Faculty Reflections on the Intersection of Equity, SEL and Digital Learning

A portion of a digital discussion board populated by faculty during professional development is shared. Faculty are responding to questions on how brain science, DEI, SEL, and Digital Learning integrate to inform teaching practice.

A portion of a digital discussion board populated by faculty during professional development is shared. Faculty are responding to questions on how brain science, DEI, SEL, and Digital Learning integrate to inform teaching practice. Preliminary analysis of this discussion board uncovered that faculty were, by and large, still in the naming stage (see Freire 1970/2000) of conceptualizing an operational definition for equity at CSD and not yet ready for reflection or action. A trauma-informed practice requires a shift in approach from a deficit model, such as “What’s wrong with this student?” to a more supportive model, such as “What internal and external factors are affecting this student?” (Thomas et al., 2019). While our centering of equity had allowed our design team to internalize this shift, examination of our second external representation suggested that perhaps faculty at large needed more time to understand and be ready to implement a trauma-informed practice. As such, we decided to narrow our focus on elements of course design that could impact virtual learning experience without necessarily requiring any additional action from either students or faculty. Literature suggests that creating and maintaining an environment of belonging can be more empowering than specific interventions that address trauma explicitly (Thomas et al., 2019). While we do not intend to imply that belonging can be created solely via course design and devoid of a larger focus on relationships, elements of course design have been found to support belonging (Ko, 2021).

Consider: Iteration

Uncertainty has been shown to promote an iterative design process (Stefaniak et al., 2022). Whitbeck (1996) encourages those working on ethical dilemmas to not hesitate in taking action as long as they are simultaneously willing to revise or combine design solutions as implications of the design case more fully emerge.

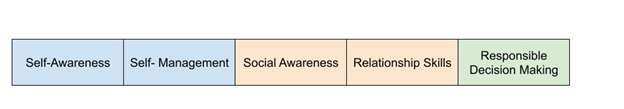

The front-end needs analysis (FEA) of past and current SEAL implementation and practice within CSD allowed us to pull recommendations from several existing frameworks including CASEL and the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE). With the formal adoption of our equity policy, however, there was a need to move beyond recommendations and into a cohesive implementation plan. Initially, we began iterating design around the CASEL framework (see Figure 3), with the goal of creating an opportunity for each SEAL competency development to be addressed at some point during the scholastic year.

Figure 3

The CASEL Framework for SEAL competency development

The CASEL framework is presented as a single bar divided into five sections. Self-awareness and self-management are seen as overlapping as are social awareness and relationship skills. Responsible decision making is the fifth stand-alone section.

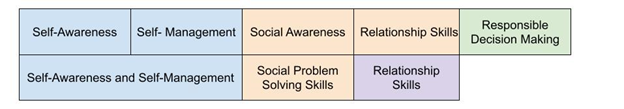

The CASEL framework is presented as a single bar divided into five sections. Self-awareness and self-management are seen as overlapping as are social awareness and relationship skills. Responsible decision making is the fifth stand-alone section.As our plans for in-person implementation evolved, a shift from the CASEL framework to the PDE framework occurred. In considering other members of our system, such as our school board and community, grounding our implementation in recommendations from the state provided concrete alignment back to our district mission and vision in a way that using a third-party tool could not. This caused a collapse of self-awareness and self-management into a single competency, refocused social awareness as social problem solving skills, and omitted responsible decision-making, at least as an explicit component of the framework (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

CASEL Framework (top) as compared to PDE SEAL Framework (bottom)

CASEL SEL Framework is laid on top of PDE SEL Framework. Again self-awareness and self-management combine. PDE conceptualizes social awareness as social problem solving skills and separates relationship skills. Responsible decision-making is dropped.

CASEL SEL Framework is laid on top of PDE SEL Framework. Again self-awareness and self-management combine. PDE conceptualizes social awareness as social problem solving skills and separates relationship skills. Responsible decision-making is dropped. Another area of uncertainty our team embraced concerned rollout timeline. Our high school operates on a modified block schedule with full credit courses meeting every other day for an entire year and half credit courses meeting every other day for a semester. Established research did not provide precedent on the various efficacy of adhering to one timeline over another during implementation beyond guidance that SEAL competency development should be explicit, systematic and focused (Jones et al., 2014).

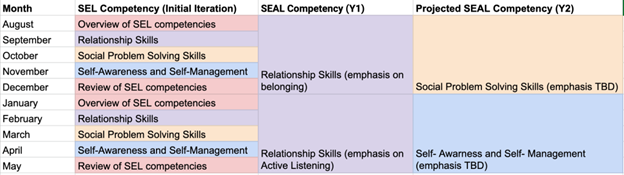

Initially, we conceptualized a rollout that would allow students opportunities to develop each PDE SEAL competency twice per year–once during fall semester and once during spring semester. This would allow students opportunities to engage in social problem solving, self-awareness and self-management, and relationship skills across multiple course disciplines at multiple times in the calendar year. However, in reflecting on data from our FEA, it was decided that in-person learners would benefit from a slower rollout with larger chunks of the scholastic year dedicated to each individual competency. In wanting to align implementation timeframe across modalities, rollout for virtual learners adopted this plan. The second iteration of our implementation timeline allowed us to provide deeper engagement with each SEAL competency before moving on (see Figure 5) albeit in an extended two-year rollout cycle.

Figure 5

Iterated Timeline of Rollout

A projected calendar for SEL implementation is shared. Initially, it was thought a different SEL competency could be focused on each month; in revision, it was decided to focus primarily on Relationship Skills alone for Year One.

A projected calendar for SEL implementation is shared. Initially, it was thought a different SEL competency could be focused on each month; in revision, it was decided to focus primarily on Relationship Skills alone for Year One.Within our distributive leadership model, our SEAL faculty liaisons collaborated with our district equity team to recommend an entire year focusing on relationship skills with two sub-focus areas to help communicate implementation to faculty and students. Sub-focus areas, such as belonging, built off of previous district initiative work of our equity team and as such, are expected to have an operational level of understanding across buildings, departments, and students. Tying relationship skills to belonging allowed for a natural entry point into development of this SEAL competency.

Consider: Developing Ongoing Feedback Loops

Whitbeck (1996) describes feedback as a collaborative process. As design is refined by this feedback, new design elements may stimulate new questions prompting additional feedback loops.

Artifact Design and Development

With a timeframe now in place, we turned our attention to artifact development. Hanover Research (2019) suggests consistent and predictable learning environments are building blocks of trauma-informed SEAL practices. As such, it was of paramount importance that any artifact we designed for building belonging in virtual courses was both consistent across subject matter and provided predictable learning pathways for virtual students.

To promote self-management and self-awareness, we developed mandatory pacing calendars inherent in our school learning management system (LMS), Canvas (see Figure 6). These pacing calendars suggested completion dates for assignments so as to help students manage time throughout the semester but do not necessarily penalize students for late submissions. (Late policies were left up to teacher academic freedom for this iteration; most teachers set a two-week window of accepted submission post pacing calendar date). Hanover Research (2019) recommends clear expectations for helping to promote psychological safety; a pacing calendar provides a visual of these expectations while offering more flexibility than a list of traditional inflexible due dates. Assignments are scheduled daily as opposed to weekly to further help students start to conceptualize how they may need to think about time management when developing a virtual learning schedule for themselves.

Figure 6

Pacing Calendar Example

A screenshot of the calendar view in Canvas is shared. Assignments are listed by due date.

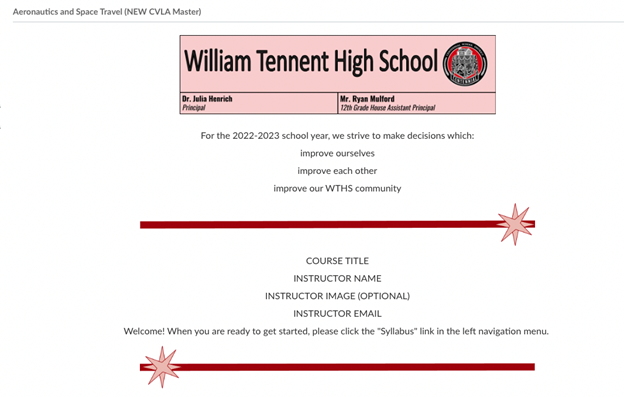

A screenshot of the calendar view in Canvas is shared. Assignments are listed by due date. Building intentional opportunities for students and teachers to define and build relationships is another critical element of a trauma-informed approach (Hanover Research, 2019). Our second mandatory design element was a generic course landing page for each fully virtual course, designed to establish belonging and provide opportunities for students to develop relationship skills in a virtual learning environment. Landing pages included teacher name, course name, teacher image, and teacher contact, as well as our three school-wide SEAL goals for the year, developed by our building administration team (see Figure 7). Again, wanting to balance agency and ownership with our teaching staff, teachers were allowed to customize elements of the landing page to include a link to a daily agenda or a weekly check-in board.

Figure 7

Course Landing Page Template

A screenshot of the course landing page is shared. The course landing page includes name of school, name of teacher, name of course, and teacher contact as well as language listing our school wide three SEL objectives.

A screenshot of the course landing page is shared. The course landing page includes name of school, name of teacher, name of course, and teacher contact as well as language listing our school wide three SEL objectives. Each landing page also contained a water-cooler type discussion board where students could crowdsource answers to questions regarding course content while simultaneously developing relationship skills.

One artifact shelved for later iteration was the use of an optional LMS feature that would create student profile pages, to help promote social awareness. As this design element would require engagement from students, it was ultimately decided that this feature did not belong in our initial rollout but could be introduced mid-year if feedback loops suggested students were open to taking more ownership of their course design.

Feedback Loops Throughout the System

An initial feedback loop came from a design reveal with members of both building administration and central administration. Open-ended feedback was solicited for each design element. In particular, the administrative team was very supportive of the pacing calendar with suggested due dates. In response to a request for more tools to promote self-awareness and self-management, sequential ordering was shared. This is an inherent LMS feature which requires students to complete assignments in a teacher-specified order. Students cannot jump ahead in the assignment sequence. After robust conversation, this feature was ultimately left off, as it was determined that such a granular level of assignment management would actually hinder learners from developing SEAL skills in self-management. Hanover Research (2019) supports the idea that students benefit from some choice which allows them opportunities to develop self-control over their environment.

Due to our school calendar, our primary source of student feedback came once courses had started, as there was not an opportunity to pull a focus group together over the summer months. (It is worth noting that on a block schedule for the scholastic year, student feedback in fall semester can inform spring course design). Students were asked a series of Likert-style questions (delivered via Google Form) to determine the extent to which various elements of course design led to an increased perception of belonging. Students were explicitly directed to consider their online learning experience holistically so as to avoid specific reactions to one teacher or course. Two open-ended questions were also included in the survey to prompt reflection on student agency as well as to collect feedback on additional arenas in which the system could have provided more support. Those specific questions were as follows:

Open-Ended Q1: What else, if anything, did you do to increase your sense of belonging in your virtual courses this month?

Open-Ended Q2: What else could have been provided for you to increase your sense of belonging in your virtual courses?

We visited hybrid classes at the beginning of the semester to inform students about the intentional design elements of the course. Wildman and Burton (1981) contend informing participants about the purpose of design elements ahead of asking them to evaluate the impact of those elements can actually lead to more accurate feedback. Our survey was distributed via school email to all virtual learners, both full-time and blended, at the end of the first month of virtual classes.

A broader scope for community feedback on culture and climate is also planned for this scholastic year. Virtual students and their families participate in our annual Climate Survey (developed and empirically validated by Hanover Research) and data is disaggregated based on learner modality. Such data provides broad stroke feedback on learner sense of belonging and can point to directions for future collaboration.

Consider: Balancing Flexibility with Fidelity

Whitbeck (1996) suggests remaining open to the idea that the parameters of design opportunities, especially those with a moral component at their center, may change over the course of time. As such, there is an inherent need of the design team to stay open to change, particularly in regards to context. The iteration of this design is specific to our current context, in which we are continuing to use a third-party digital curriculum to facilitate virtual learning. As our district seeks to develop and digitize its own digital resources, there may be additional avenues through which SEAL competency development can be embedded within our very curriculum. Dusenbury et al. (2015) suggest an approach where SEAL competency development opportunities are embedded in curriculum can be equally effective to adding or layering on an entirely separate curriculum.

Furthermore, this iteration was by-and-large implemented and owned by our administration team. This was intentional and due to the two-fold newness of both our initiatives: faculty were being asked to facilitate 100% virtual learning for the first time and were still uncovering how to conceptualize their own social-emotional learning needs and their relationship of those needs to a trauma-informed practice. Brackett et al. (2010) have found faculty who have a deeper understanding of their own social-emotional needs are better equipped to model and provide social-emotional learning opportunities for their students. Continuing professional development in both digital course facilitation and SEAL may allow our faculty the opportunity to develop greater agency and ownership of trauma-informed course design.

While the scope, design team members, and points of access to our audience may change as both our digital learning and SEAL initiatives continue to evolve, what endures is our commitment to designing for equitable SEAL competency development regardless of modality.

Designer Reflections

As design cases are intended to provide precedent to the field (Boling, 2010) we will try to summarize major lessons learned from our practice, while acknowledging that design cases are not typically intended to speak to the universal (Gray & Boling, 2016). Despite our commitment to de-siloing our roles as a unified design team, we still felt the need for additional perspectives that could contribute to both richer front-end design and increased feedback loops. As we were still developing an understanding of the district’s intentions to operationalize a trauma-informed approach, we chose to center equity as our core design value. However, a key perspective missing from our design team was the Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, a position that was vacant within the district at the time of this design. While it was reassuring to realize a commitment to equity lives within our school systems as opposed to any one individual, including those with a formal background in inclusive educational practices would have benefited the initial framing of our design opportunity.

Additionally, while we included secondary students’ feedback about the impact of the design elements on their feelings of belonging, future iterations could be strengthened by including their perspectives in the actual design phase, using a participatory design approach (see Konings et al., 2014). Finally, building on the distributive leadership model used in CSD, a richer approach to design and feedback would include the perspectives of district teacher leaders, the Superintendent's Parent Advisory Council and the Superintendent’s Student Advisory Council.

Centering equity as a core shared organizational value also safeguards the system against varied levels of individual commitment. Surveying our faculty to capture their personal conceptualization of the intersection of equity, SEAL, and digital learning, uncovered a group that was open to learning but not yet ready to implement change. Although we desired increased participation at the design table, understanding faculty needs allowed us to approach their reticence with a trauma-informed lens ourselves. Furthermore, by being open and transparent about our “top-down” design plans, faculty who were ready to participate ended up adding their own unprompted elements for SEAL competency development to courses–such as weekly check-in Padlets and open office hours specifically for the logistics of online learning.

When working within a system with so many components, it is essential for communication to be clear and for what is being communicated to be reflective of the audience’s background knowledge and implementation readiness. While collaboration allowed us to share our expertise in digital and social-emotional learning with each other, developing new vocabularies for both of our proverbial silos, our relationships with additional members of the system uncovered a varied level of understanding of our work. For example, in sharing our ideas for a common course landing page design, we discussed how accessibility considerations led us to use text to direct students to common navigation paths instead of a series of buttons. This discussion led the central leadership team into a rich discussion of their understanding of accessibility, ultimately expanding it to include elements of digital accessibility. This was an important reminder that for us to increase opportunities for students to experience belonging, we needed to ensure all members of the system felt as if they understood our vision and belonged to it first.

Conclusion

As K-12 learning modalities expand beyond traditional face-to-face classroom offerings, systems must be redesigned (or designed anew) to provide places of belonging for online learners. When SEAL competency training is integrated into online learning environments as they are developed, opportunities to foster personalized student growth and development become inherent. The purpose of this design case is to help begin establishing precedent on how a trauma-informed approach can inform online course design with the specific intention of allowing opportunities for SEAL competency development. Centering equity as our course design value, we turned to the field of ethics to help guide our design process. In explicitly breaking down this process to highlight both challenges and opportunities encountered during design, this case adds to the growing body of practical application research on trauma-informed approaches.

References

Baaki, J., & Tracey, M. (2019). Weaving a localized context of use: What it means for instructional design. Journal of Applied Instructional Design 8 (1), 2-13.

Baaki, J., Tracey, M. W., & Hutchinson, A. (2017). Give us something to react to and make it rich: Designers reflecting-in-action with external representations. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 27 (4), 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9371-2

Boling, E. (2010). The need for design cases: Disseminating design knowledge. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 1 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v1i1.919

Brackett, M., Palomera, R., & Mojsa, J. (2010). Emotion regulation ability, burnout and job satisfaction among secondary school teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 47 (4), 406-417. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20478

Centennial School District (CSD). (2021). Trauma-informed approach (146.1). https://go.boarddocs.com/pa/csd/Board.nsf/Public

Centennial School District (CSD). (2022). Mission, vision, beliefs, values, goals, etc. https://www.centennialsd.org/our_district/mission__vision__beliefs__values__goals__etc_

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2022). Fundamentals of SEL. https://casel.org/fundamentals-of-sel/what-is-the-casel-framework/

Dick, W., Carey, L., & Carey, L. (2005). The systematic design of instruction (6th ed.). HarperCollins.

Dusenbury, L., Calin, S., Domitrovich, C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2015). What does evidence-based instruction in social and emotional learning actually look like in practice? A brief on findings from CASEL’s program reviews. CASEL. https://drc.casel.org/blog/resource/what-does-evidence-based-instruction-in-social-and-emotional-learning-actually-look-like-in-practice/

Freire, P. (1970/2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Frydman, J. S., & Mayor, C. (2017). Trauma and early adolescent development: Case examples from a trauma-informed public health middle school program. Children & Schools, 39 (4), 238-247. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdx017

Gagné, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K. C., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of instructional design (5th ed.). Thomson Wadsworth.

Gray, C. & Boling, E. (2016). Inscribing ethics and values in designs for learning: A problematic. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64 (5), 969-1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9478-x

Gray, C. M., Dagli, C., Demiral-Uzan, M., Ergulec, F., Tan, V., Altuwaijri, A. A., Gyabak, K., Hilligoss, M., Kizilboga, R., Tomita, K., & Boling, E. (2015). Judgment and instructional design: How ID practitioners work in practice. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 28 (3), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21198

Hanover Research. (2019). Best practices for trauma-informed instruction. https://wasa-oly.org/WASA/images/WASA/6.0%20Resources/Hanover/BEST%20PRACTICES%20FOR%20TRAUMA-INFORMED%20INSTRUCTION%20.pdf

Hanson, R. F. & Lang, J. M. (2016). A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment, 21 (2), 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516635274

Harless, J. H. (1970). An ounce of analysis (is worth a pound of objectives). Guild V Publications.

Herman, K., Baaki, J., & Tracey, M. (2022). “Faced with given circumstances”: A localized context of use approach. In B. Hokanson, M. Exter, M. Schmidt, & A. Tawfik. (Eds.). Toward inclusive learning design: Social justice, equity, and community. Springer-Verlag.

Jones, S. M., Bailey, R. & Jacob, R. (2014). Social-emotional learning is essential to classroom management. Phi Delta Kappa, 96, 19-24. https://kappanonline.org/social-emotional-learning-essential-classroom-management-jones-bailey-jacobs/

Ko, M. E. (2021). Course design equity and inclusion rubric (Version 1.0.1). Stanford University Department of Bioengineering. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1BbrJNgH1m-ikU8t8RzwbvdlBEhkNAPEOw7iQXae1o4I/edit

Konings, K. D., Seidel, T., & van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2014). Participatory design of learning environments: integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instructional Science, 42 (1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-013-9305-2

Maynard, B. R., Farina, N., Dell, N. A., & Kelly, M. S. (2019). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 15 (1-2), e1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1018

Moore, S. (2021a). SEL at a distance: Supporting students online. W.W. Norton & Company.

Moore, S. (2021b). The design models we have are not the design models we need. The Journal of Applied Instructional Design, 10 (4). https://dx.doi.org/10.51869/104/smo

Moore, S. (2022). Reclaiming resilience: Building better systems of care. Educause Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2022/7/reclaiming-resilience-building-better-systems-of-care

Morrison, G. R., Ross, S. M., Kalman, H., & Kemp, J. (2013). Designing effective instruction (7th ed.). Wiley.

Ngo, V., Langley, A., Kataoka, S. H., Nadeem, E., Escudero, P., & Stein, B. D. (2008). Providing evidence-based practice to ethnically diverse youths: Examples from the Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program. Journal Of the American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47 (8), 858-862. https://doi.org/10.1097/chi.0b013e3181799f19

Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE). (2022). Elementary and secondary school relief fund. US Department of Education. https://oese.ed.gov/offices/education-stabilization-fund/elementary-secondary-school-emergency-relief-fund/

Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE). (2022). Pennsylvania career ready skills. Commonwealth of PA. https://www.education.pa.gov/K-12/CareerReadyPA/CareerReadySkills/Pages/default.aspx

Smith, A. K., Watkins, K. E., & Han. S. (2020). From silos to solutions: How one district is building a culture of collaboration and learning between school principals and central office leaders. European Journal of Education Research, Development, and Policy, 55 (1), 58-75. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12382

Smith, K. M. (2010). Producing the rigorous design case. International Journal of Designs for Learning, 1 (1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.14434/ijdl.v1i1.917

Stefaniak, J., Baaki, J. & Stapleton, L. (2022). An exploration of conjecture strategies used by instructional design students to support design decision-making. Educational Technology Research and Development 70 (2), 585–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-022-10092-1

Stefaniak, J., Luo, T. & Xu, M. (2021). Fostering pedagogical reasoning and dynamic decision-making practices: a conceptual framework to support learning design in a digital age. Education Technology Research Development, 68 (6), 2225-2241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-09964-9

Svhila, V. (2020). Problem framing. In J. K. McDonald & R. E. West (Eds.), Design for learning: Principles, processes, and praxis. EdTech Books. https://edtechbooks.org/-VTiX

Tawfik, A. A., Shepherd, C. E., Gatewood, J. et al. (2021). First and second order barriers to teaching in K-12 online learning. TechTrends 65, 925–938 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00648-y

Thomas, M. S., Crosby, S., & Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education, 43 (1), 422-452. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732x18821123

Tracey, M. W., & Hutchinson, A. (2018). Reflection and professional identity development in design education. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 28 (1), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-016-9380-1

True, J., Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2007). Punctuated equilibrium theory: Explaining stability and change in policymaking. In Paul A. Sabbatier (Ed.), Theories of the policy process (pp. 157-187). Westview Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494284-3

Venet, A. S. (2021). Equity-centered trauma-informed education. W.W. Norton & Company.

Whitbeck, C. (1996). Ethics as design: Doing justice to moral problems. Hastings Center Report, 26 (3), 9-16. https://doi.org/10.2307/3527925

Wildman, T. M. & Burton, J. K. (1981). Integrating learning theory with instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 4 (3), 5-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02905318=