Toward a Shared Vision of Multicultural Teacher Education through Collective Self-Study

This research explores a cooperative self-study project that 14 university-based teacher educators at the University of Iceland participated in for two years. The study aimed to develop a dialogic space that would mobilize teachers’ diverse experiences and perspectives to build a framework for multicultural teacher education. The teacher educators engaged in self-study to understand in what ways (if any) dialogue could aid their understandings of how their cultural backgrounds influence their work as teacher educators. Specifically, teacher educators sought to understand how this dialogic space could allow them to problematize and rethink teacher education collectively. The data collected included focus group interviews, self-interviews, and audio-recordings of meetings. Art-based analysis methods via the co-construction of sculptures and poems were used to create a dialogic space (Freire, 1970) which helped teacher educators develop a shared agenda for collective transformation.

Ultimately, this inquiry heightened participants’ awareness of the complex process of negotiating a shared platform beyond theoretical and disciplinary boundaries, one that could help them align and (re)commit themselves to educate teachers in ways that prioritize equity and justice (Zeichner, 2018; Kitchen et al., 2016).

Context

The increasing immigrant population within Icelandic schools has created a demographic imperative for pursuing multicultural approaches to education and teacher education. Never before has it been more important for teacher education programs to prepare teachers multiculturally, necessitating a collective transformation of the role of teacher educators in Iceland, who largely embody dominant Icelandic identities (Sleeter, 2001).

Critical multicultural education demands the interrelated transformation of self, teaching, and society (Gorski, 2010; Souto-Manning, 2013). Working from this perspective, we sought to transform our roles as teacher educators to reconceptualize our practices using collective self-study as our practical methodology. Our inquiry fostered increased meta-awareness of our roles as teacher educators, helping us reconsider the positioning of our diverse backgrounds, practices, and experiences (Kitchen et al., 2016). This paper describes how the authors negotiated with each other and their colleagues in the process of creating a dialogic space for the group to develop a shared vision for multicultural teacher education.

Aims

This collective self-study (Bodone, et al., 2004; Samaras, 2011) aimed to document and analyze the process whereby 14 university-based teacher educators in Iceland co-designed and negotiated a learning community committed to multicultural teacher education. Teacher educators worked to become aware of their identities and practices, developing a critical understanding of how they either resist or reify existing structures of inequity. In so doing, teacher educators re-envisioned their roles and practices as teacher educators (Mitchell et al., 2009; Gísladóttir, et al., 2019; Guðjónsdóttir, et al., 2017; Jónsdóttir et al., 2015; Jónsdóttir et al., 2018).

A shared commitment to maintaining a dialogic space defines this research. In understanding the creation of the dialogical space and how it develops from within, we bring together Freire’s (1970) notion of dialogical space and Bakhtin’s (1984) notion of interior monologue. We understand dialogical space as an encounter between individuals within a temporalized space in which they attempt through shared reflection and action to act upon the world they want to transform. In their attempt to name the world, the world “reappears to the namers as a problem and requires of them a new naming” (Freire, 1970, p. 76). Thus, naming the world becomes a continued “act of creation and re-creation.” For dialogical space to thrive, dialoguers need to find ways to develop horizontal relationships built on mutual trust. For this to happen, Freire asserts, the dialogue must be founded upon love, humility, and faith in humankind.

Bakhtin’s (1986) notion of interior monologue becomes essential in identifying and interrogating the very foundation of dialogic space. The notion of interior monologue calls attention to how individual monologues are never just monologues. Dialogue, from a Bakhtinian perspective, has infiltrated every word and has both roots stretching into the past and the potential to progress forward to a limitless world. For Bakhtin, “dialogue” describes how the word itself is a site of battle in which different voices collide with and interrupt each other. This is especially true in the creation of new knowledge or a shared vision. In attempting to understand the complexity of developing a dialogical space for moving toward multicultural teacher education, the concept of interior monologue allows us to interrogate and explore what happens underneath the surface as ideas are brought into being through lived events or dialogical encounters between individuals and the world.

To name and interrogate practices and identities, teacher educators in this study engaged in the critical cycle (Souto-Manning, 2010). The critical cycle offered a framework to thematically investigate experiences, lived realities, and identities as teacher educators. It also allowed teacher educators to critically problematize teaching and work toward praxical transformation dialogically (Souto-Manning, 2019).

Methods

This research traces how a dialogic space was created across fields of professional expertise and disciplinary backgrounds (Harrison et al, 2012; Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2014; 2015; 2019; Pithouse-Morgan et al., 2016). Methods included rhetorically mapping our existing understandings of multicultural education, dialogically problematizing paradigms in order to frame difference historically (Goodwin et al., 2008), and developing a shared understanding of multicultural education (Banks, 2013; Kitchen, et al., 2016).

Data, collected for two years, included focus group interviews, self-interviews, audio-recordings, transcripts of meetings, and artifacts. Analysis engaged art-based methods, via the co-construction of sculptures and poems, to make visible negotiations and tensions. Iterative analysis allowed for further work.

First, teacher educators documented their understandings and experiences of multicultural education via collective self-interviews guided by questions formulated by the group (Meskin et al., 2014). In small groups, teacher educators took turns interviewing each other. Each interview lasted about 30 minutes. Interviews were recorded and each member transcribed their own interview. In the analysis, participants re-read the transcripts of their own interviews to identify "emotional hot points" (Cahnmann-Taylor, et al., 2009) they wanted to explore by creating sculptures.

Creating the sculptures allowed teacher educators to make tangible their internal and abstract ideas. This, in turn, allowed them to interrogate their ideas dialogically and weave them together to form a collective understanding that would enable them to move towards multicultural teacher education (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Examples of Sculptures Made by the Groups

Explanations of the sculptures were video recorded and transcribed. Poetic inquiry was used to analyze these transcripts and distill complicated clouds of ideas down to essential concepts. Inspired by “erase poetry” (Faulkner, 2012; Pithouse-Morgan, et al., 2014), teacher educators read the transcripts and erased words that lacked vital meaning for them in terms of multicultural education, leaving only words important for their collective work (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

An Example of Transcript and the Words Holding a Vital Meaning

Then, each group rearranged words into collective poems, which comprised the theoretical foundation upon which the group would build. Finally, through dialogic engagement, the teacher educators identified three pillars essential for guiding their work.

Participants

The 14 participants form a diverse, interdisciplinary, and dynamic group of educators with different backgrounds and experiences. Nine had Icelandic heritage and spoke Icelandic natively. Five spoke other mother tongues and were brought up in different countries. Each member had different academic experiences and held different positions within the School of Education, ranging from PhD students and adjuncts to assistant professors, associate professors, and full professors. Some were new and others experienced. Each brought different theoretical and methodological orientations to the group. In particular, some were familiar with action research and self-study methods, while for others these forms of research were new. The authors offered participants to use pseudonyms in this paper, but all opted to use their real names.

Negotiating a Starting Point

Creating a shared vision for the group did not happen without effort. The first meeting concerned how the School of Education was preparing student teachers to incorporate multicultural education into their teaching practice. This meeting attracted 12 participants. We discussed the need to map out current work and our understanding of multicultural education. The conversation was rich with different theoretical and methodological orientations. First, teacher educators explored participants' different experiences and expectations. The conversation traversed several topics: how multicultural education emerged in our educational practices, areas where we could improve, and how multicultural perspectives were present in course syllabi. The discussion then turned toward the critical importance of design-based research. As teacher educators discussed the steps for working towards multicultural teacher education, they discussed how they could distribute articles on the topic, mobilize beneficiaries, and empower teachers. The conversation ended with a discussion about designing a questionnaire to send to colleagues within the School of Education. Yet, as soon as the idea of the questionnaire emerged, it began to overshadow other ways of approaching the task.

As a head of the faculty, Gunnhildur observed that many courses included an emphasis on multicultural education. However, how individual teacher educators were carrying this out within their coursework was unclear. Gunnhildur thought that the questionnaire was an essential way to ascertain how our colleagues were approaching multicultural education.

Karen, however, did not agree. As a self-study researcher, she did not prioritize gathering this information over the first-hand praxical transformation the group wanted within their program. She believed that in sending out a questionnaire the group was uncritically taking an authoritative stance.

To make her point, Karen pointed to the pronoun "we" in the group’s initial research focus – "how do we prepare student teachers for practice in schools concerning multicultural education?" Karen intended to highlight that the group first needed to define this "we" who was responsible for the preparation of student teachers. She wondered:

Did the pronoun refer to this discussion group? And was the group's task to focus on the steps being taken to understand what could be learned from our processes? Or did the pronoun refer to all of the teacher educators within the School of Education? And what were we going to do with that information? Would that give us the potential to carry through the changes we envisioned?

Karen thought the group needed to explore their own practices so they could become agents of change before moving forward. Karen was committed to self-study as an essential pathway for the group's work. Yet these ideas were met with hesitation and resistance, as the group's discussion repeatedly circled back to the questionnaire.

Gunnhildur left the meeting feeling as though the group was one step closer to understanding how to map out the work happening at their institution. However, she realized that people brought multiple theoretical and methodological experiences regarding multicultural education into the meeting, and not everyone agreed with the methodological approach of this project. She had never considered doing a self-study. Karen left the session feeling frustrated with the discussion of the questionnaire. Her experiences in teacher education had taught her that self-study was often considered to lack validity as a methodological approach for developing knowledge about and for teacher education (Johnson-Lachuk, et al., in press). The conversation confirmed her understandings of how self-study was often marginalized within her institution. She knew that if she was to be part of this group, self-study had to be one of the methodological choices utilized.

Turning Towards Self-Study

Leading up to the second meeting, Karen shared her concern with her colleague Hafdís Guðjónsdóttir, an experienced self-study researcher (Bodone, et al., 2004; Samaras, et al., 2012). Hafdís was interested in joining the project but had been unable to fit the meetings into her schedule. Karen shared how sending out a questionnaire had been proposed, indicating that she felt she lacked the authority to push the group to use new methods.

Hafdís readily agreed to attend the next meeting and came swirling in like a "self- study" tornado. The discussion continued where it had left off. Teacher educators exchanged ideas, ranging from sharing publications on how teachers should think about multiculturalism to using results from existing research in our courses. Karen was discouraged that the discussion did not create space for teacher educators to transform their thinking. In her mind, the group's focus was undergirded by an implicit assumption that teacher educators were somehow the experts and not in need of transformation themselves. As Karen struggled to articulate her concern, Hafdís explained that, while surveys might be useful in gaining an overview of a phenomenon, they were seldom effective because of low participation rates. She continued by asking the group, "What do we want to do with our findings? How important is it for us to see what we are doing at the same time as we are mapping out what is happening at the university?” She proposed that we interview each other in small groups.

This technique, she asserted, would yield two outcomes: practicing questions that could then be used with our colleagues, and getting to know each other’s experiences and knowledge.

The group approved of this idea. Quickly, interview questions were developed: 1) What is your understanding of multicultural education? 2) Where does your interest in multicultural education come from, or why have you become involved in multicultural education? 3) Can you name examples of your educational practices reflecting these theoretical underpinnings? 4) Can you identify how you develop environment, learning spaces, and/or participation in the spirit of multicultural education? The large group was divided into groups of three, and a time was scheduled to conduct the interviews.

Negotiating a Shared Vision Towards Multicultural Teacher Education

In December, the interviews were conducted and transcribed. Gunnhildur felt this change in focus had released teacher educators from the disagreement over the questionnaire. Everybody agreed these interviews were essential for further development. After the interviews, Karen believed the group had effectively turned the process towards themselves and were now on a path with the potential for negotiating a shared vision and understanding of their work. However, the group was just getting started. Now they needed to develop a constructive framework for future directions. Not everyone was convinced about the direction this project was taking, and Karen knew she needed to demonstrate the importance of self-study in developing pedagogical and ontological knowledge for teacher education.

In moving ahead, Karen suggested constructing an art-based framework in which teacher educators would individually begin identifying essential points in their interviews that they would then bring into small groups to create a collective sculpture. While Gunnhildur found this idea exciting, she worried that the process would be too time-intensive, and the sculpture idea might detract from the group's focus. Before the next meeting, Karen appeared in the teacher’s lounge with two big suitcases full of recyclable material. Gunnhildur, caught off guard, asked Karen if she meant that teacher educators would “create actual sculptures in the meeting." "Of course," Karen replied. "What did you think we were going to do?"

Gunnhildur laughed and admitted she thought that teacher educators were going to create an imaginary sculpture, not a real product. She could not envision where making an actual sculpture would lead the research process. She wondered whether what Karen proposed was even research and whether teacher educators would buy into this process. She felt that she was asking too much in having teacher educators dedicate a whole-session to "arts and crafts." But faced with Karen's determination, she realized she could not turn back.

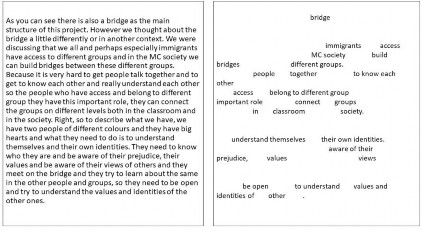

At the beginning of the session, the materials provided for the art-based analytical work were displayed. The session commenced with individual time to engage with each person's interview, identifying points teacher educators wanted to address further in small groups. The following concepts emerged: reflecting on individuals’ home culture; assisting immigrant children who did not speak Icelandic; removing hindrances; making the unconscious conscious; identifying students' strengths and cultural resources; having courage; addressing prejudices and privileges; securing immigrants’ participation; reflecting on one's disposition; finding pathways to collaboration; bilingual children, poverty, gender equity, equal opportunities, and the idea that the school should reflect society. In small groups, teacher educators listened to each other’s points before moving forward to using sculpture to create a shared vision. Teacher educators were randomly assigned to groups of four, with Karen and Gunnhildur assigned to the same group.

While some individuals were very focused on the school and how they could help student teachers to work with students of diverse backgrounds, others were more concerned with how these ideas played out within society. The discussion shifted from mere dialoguing about thoughts to dialoguing through the recyclable material at hand. An incident in Gunnhildur’s and Karen’s group illuminates how creating the sculptures provided a space to negotiate shared meaning and to ensure one’s ideas were included (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Our Sculpture in the Making

In discussing how to proceed with our sculpture, Gunnhildur expressed concerns about helping student teachers create conditions within schools to work with students' diverse backgrounds. Karen asked Gunnhildur if she wanted to focus on that in building our sculpture, or if we should start with our understanding of multiculturalism. Gunnhildur was not sure what Karen meant and asked if she was thinking of this in the abstract. Karen explained that multicultural education was also about people’s journeys and how they connected with others and learned about new cultures. As they began to work on the sculpture, Karen engaged in an in-depth discussion about self and society with Anh-Dao, another member of the group. They discussed the relationship between a person's social position and privilege. Karen and Anh-Dao used the silver-colored candy bulbs in the picture to represent the different locations of privilege (see Figure 3); on top of it, inside of it or under it, described the different social positions. Feeling excluded from the conversation, Gunnhildur and Hrönn (the fourth colleague) suggested that schools needed to be included in the sculpture, but they felt they did not get a response. They initiated their own conversation where they admitted they were not relating to Karen and Anh-Dao's creation.

“Hey, we are thinking about the school,” Hrönn said firmly.

“The school?” answered Anh-Dao with a puzzled tone in her voice. “Yes, we want to have the school there,” Hrönn continued.

“Yes,” Karen responded pointing to the sculpture, “so this is the society. We have the individuals there. Then we will have the school around the society. What do you think about that?"

"I want to make this transparent," Hrönn said. "So the child or the individual and society are reflected within the school."

"Okay," Karen replied, and returned to discussing privilege and social position with Anh-Dao.

Gunnhildur and Hrönn continued their discussion. Gunnhildur determined that the school needs to be visible in the sculpture, asked Hrönn how they could include it in the sculpture. Together, they created a large bridge and brought it to the table.

"Can we place a bridge here?" Hrönn asked. Karen replied affirmatively but wondered if it could be turned into some walls instead.

"I want a bridge rather than a wall," Gunnhildur declared. Hrönn agreed.

Karen persisted in trying to convince them that it might be better to turn their bridge into a wall, pointing out space constraints. She suggested that we could place the wall at the edge of the sculpture, indicating that it had to surround and reflect society.

But Gunnhildur was adamant about the bridge, and Karen reluctantly agreed.

Gunnhildur and Hrönn placed the bridge in the center of the sculpture.

"Now you understand," said Gunnhildur, pointing to the bridge at the heart of the sculpture and asking if everybody was okay with this. Nobody disagreed, and the bridge/school ended up being one of the centerpieces of the sculpture. In sharing the overall message of our sculpture, Gunnhildur and Hrönn reflected upon this experience, explaining how happy they were having the bridge in the sculpture. They had tried to explain how the school represented a bridge between society, school, and children but felt as Karen and Anh- Dao did not see this option because they were so deep in their discussion. The material allowed them to insert the bridge as they explained their point of view. This was important because if they had not gotten their attention they would have felt that their voices were not equal to the others in the group.”

The final step in developing a shared vision for our group was to use transcripts from each group's explanation to craft poems. We read through the transcripts, and erased words that lacked vital meaning for us in terms of multicultural education, leaving only the words we thought were necessary for our collective work. Then we rearranged the words into poems. For example:

personal journey / institutional journey / societal journey

starting with ourselves / do I have prejudices / how can I overcome that

the teacher / learning and growing / creating opportunities / supporting students

speaking from experience / without shame / about poverty / social position

students participating / their voices heard / requires structure support

dialogue / listening / the courage to say I want this included

the classroom / reflection of society / equality and respect

children / as creators / of opportunities

The self-study research process provided us with a pathway for capturing and representing the multiple experiences found in our group, which comprised the theoretical foundation from which the group would grow. Finally, through a dialogic engagement with the poems, we began to identify highlights from which we constructed the pillars of our future work.

These were:

-

Belonging;

-

Critical dialogue, encompassing the consideration of multiple perspectives;

-

Transformation of self, classroom, and society.

Discussion

Following Bakhtin’s dialogism, we present our interior monologues as we engaged in this process. Our inner talk illuminates how every utterance is just the tip of the iceberg on the surface, with a whole slew of feelings and experiences down in the depths. Our inner monologues show how we worked through tensions in our relationships to create stronger communication. As such, our inner monologues illustrate some of the complexities of engaging in dialogue with one another. At times, participants do not feel heard or capable of listening. Ultimately, collective self-study puts us on a challenging, albeit productive, pathway towards furthering our personal and professional development in multicultural teacher education.

Self-study provided us with the space to explore the intricate process of drawing on each other’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds, along with our experiences of teaching and teacher education, to develop individually and collectively. This exploration serves as a site for strengthening our relationships, aligning our practices, and affirming our commitment to prioritize equity and justice. The complexity embedded in this process is important to acknowledge and address. In preparing student teachers to work with students of diverse backgrounds, we, as teacher educators, need to be capable of creating an authentic dialogic space for discussion beyond institutional, geographical, theoretical, and disciplinary boundaries.

Self-study research was a powerful avenue for our group for identifying, problematizing, and transforming our individual and collective understandings of our roles and practices as teacher educators (LaBoskey, 2004). From this experience, we see such dialogue as an important site for student teachers to develop the trust needed to move toward multicultural education.

Implications

This work has taught us that in working with a group of persons with diverse commitments and viewpoints, certain features must be present to create a shared vision. First, we need to create authentic spaces where individuals can bring in different knowledge, experiences, artifacts, and materials to develop a shared understanding that is respectful of diverse cultures. Such a space cannot be judgmental or evaluative, but rather must be open-minded and inclusive of diverse viewpoints. Second, we need to find ways to slow down so that we can better attend and listen to one another. In short, we need to be present and mindful. Finally, we need to capture our own dialogue to explore how we are (or are not) listening and being responsive to each other. Being aware of all those different components is important to develop the trust and understanding required for collaboration.

References

Banks, J. A. (2013). Multicultural Education: Characteristics and goals. In J. A. Banks & C. M.Banks (Eds.), Multicultural education. Issues and perspectives (8th ed., pp. 3– 23). John Wiley.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. Translated by Vern V. McGee. University of Texas Press.

Bodone, F., Guðjónsdóttir, H., & Dalmau, M. (2004). Revisioning and Recreating Practice: Collaboration in Self-Study. In J.J. Loughran, M.L. Hamilton, V.K. LaBoskey, & T.L. Russell (Eds.), International Handbook of Self-Study of Teaching and Teacher Education Practices (pp. 743-784). Springer.

Cahnmann-Taylor, M., Souto-Manning, M., Wooten, J., & Dice, J. (2009). The art and science of educational inquiry: Analysis of performance-based focus groups with novice bilingual teachers. Teachers College Record, 111(11), 2535–2559.

Faulkner, S. L. (2012). Frogging it: A poetic analysis of relationship dissolution. Qualitative Research in Education,1(2), 202-227. doi:10.4471/qre.2012.10

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Gísladóttir, K. R., Guðjónsdóttir, H., & Jónsdóttir, S. R. (2019). Self-study as a pathway to integrate research ethics and ethics in practice. In R. Brandenburg & S. McDonough (Eds.), Ethics, self-study and teacher education. Springer.

Goodwin, A. L., Cheruvu, R., & Genishi, C. (2008). Responding to multiple diversities in early childhood education. In C. Genishi & A. L. Goodwin (Eds.), Diversities in early childhood education: Rethinking and doing (pp. 3-10). Routledge.

Gorski, P. C. (2010). The challenge of defining multicultural education. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-eXr

Guðjónsdóttir, H., Jónsdóttir, S. R., & Gísladóttir, K. R. (2017). Collaborative supervision: Using core reflection to understand our supervision of Master’s projects. In R. Brandenburg, K. Glasswell, M. Jones & J. Ryan (Eds.), Reflective theory and practice in teacher education (237-255). Springer.

Harrison, L., Pithouse-Morgan, K., Connolly, J., & Meyiwa, T. (2012). Learning from the first year of the transformative education/al studies (TES) project. Alternation, 19(2), 12-37.

Johnson-Lachuk, A., Gísladóttir, K. R. & DeGraff, T. (in press). Collaboration, narrative and inquiry that honors the complexities of teacher education. Charlotte: Information age publication.

Jónsdóttir, S. R., Gísladóttir, K. R., & Guðjónsdóttir, H. (2015). Using self-study to develop a third space for collaborative supervision of master’s projects in teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 11(1), 32-48.

Jónsdóttir, S. J., Guðjónsdóttir, H., & Gísladóttir. (2018). Að vinna meistaraprófsverkefni í námssamfélagi nemnda og leiðbeinenda. Tímarit um uppeldi og menntun/Icelandic journal of education, 27(2), 201-223.

Kitchen, J., Fitzgerald, L. & Tidwell, D. (2016). Self-study and diversity. In J. Kitchen, D. Tidwell, & L. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Self-Study and Diversity II: Inclusive Teacher Education for a Diverse World, pp 1-10. Sense Publishers.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamiltons, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (Vol. 2, pp. 817- 869). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Meskin, T., Singh, L., & Van der Walt, T. (2014). Putting the self in the hot seat: Enacting reflexivity through dramatic strategies. Educational research for social change, 3(2): pp. 5-20. doi: 10.1080/09518390903426212.

Mitchell, C., Pithouse, K., & Moletsane, R., (2009). The social self in self-study; Author conversations. In K. Pithouse, C., Mithell, & R. Moletsane (Eds.), Making connections: Self-study & social action. (pp. 11-23). Peter Lang.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., & Samaras, A. P. (2014). Thinking in space: Learning about dialogue as method from a trans-continental conversation about trans-disciplinary self-study. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on the Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices, East Sussex, England (167-170). University of Auckland.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., & Samaras, A. P. (2015). The Power of “We” for personal and professional learning. In K. Pithouse-Morgan, K., & A.P. Samaras, A. P. (Eds.), Polyvocal professional learning through self-study research. (pp. 1-20). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., & Samaras, A. P. (2019). Polyvocal play: A poetic bricolage of the way of our transdisciplinary self-study research. Studying Teacher Education, 15(1), 1-15. doi:10.1080/17425964.2018.1541285

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Coia, L., Taylor, M., & Samaras,A. P. (2016). Exploring methodological inventiveness through collective artful self-study research. LEARNing Landscapes, 9 (2), 443-460. doi: 10.1080/09518390903426212

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Pillay, D., Naicker, I., Morojele, P., Chikoko, V., & Hlao, T. (2014). Entering an ambiguous space: Evoking polyvocality in educational research through collective poetic inquiry. Perspective in education, 32(4), 149-170.

Samaras, A. P., Guðjónsdóttir, H., McMurrer, J. R., & Dalmau, M. C. (2012). Self-study as a professional organization in pursuit of a shared enterprise. Studying teacher education: A journal of self-study of teacher education practices. 8(3), 303-320.

Samaras, A. P. (2011). Self-study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry. Sage.

Sleeter, C. (2001). Preparing teachers for culturally diverse schools: Research and the overwhelming presence of whiteness. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(2), 94-106.

Souto-Manning, M. (2010). Freire, teaching, and learning: Culture circles across contexts. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Souto-Manning, M. (2013). Multicultural teaching in the early childhood classroom: Strategies, tools, and approaches, Preschool-2nd grade. Teachers College Press.

Souto-Manning, M. (2019). Toward praxically-just transformations: interrupting racism in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45(1), 97-113.

Zeichner, K. (2018). The struggle for the soul of teacher education. Routledge.