When teaching a complex practice like teaching a challenge for teacher educators is to keep the task of teaching whole while managing the parts that must be learned. In this self-study, two teacher educators critically examine their practice in search of both clarity and coherence with regard to the intricate interplay between the teaching of the parts of teaching while maintaining a vision of the simultaneous and integrated practice of skilled teachers. We elaborate on three threads that emerged as critical to our quest for coherence: modeling, sustaining feedback, and the linking of the macro and micro facets of teaching.

Our work preparing early childhood and elementary education undergraduate-level (P-5) teacher candidates (TCs) is situated across contexts: a mid-sized private university and local elementary schools. Amy teaches science and social studies methods courses on campus and has developed a thick partnership with a charter school where science and social studies are taught daily. In this early practicum, TCs rehearse whole-class lessons on campus, plan lessons with mentor teachers, and teach one whole group lesson per week in the classroom. Jeanne’s literacy courses (at the same institution) include an early foundational literacy course with embedded field experience in which TCs tutor for the entire semester and a literacy practicum in which TCs are planning and teaching lessons in an EL school two mornings each week. We encounter and confront daily challenges and assumptions related to TC learning and development as it occurs within and across university and school-based settings.

We characterize this work as situated along the theory-practice edge because we (together with our TCs) traverse back and forth across the boundaries between the college classroom, where TCs are learning about theory-informed practice and research-based strategies and the elementary school where TCs are engaged in the complex work of teaching in the complicated context of classrooms. We, like Langdon and Ward (2015) believe that teacher educators (TEs) require specialized pedagogical knowledge and skill that is different from that required to teach P-5 students. Therefore, as TEs working in this space we are called upon to identify, examine, and often times design teacher educational pedagogies that scaffold TC learning in and from practice (Lampert, 2010). We are challenged to pull the threads of TCs’ developing practice into the university context as we are also pulling the threads of TCs’ nascent understanding of theory into the P-5 context. These threads do not exist side-by-side (in parallel) but are twined together, partially unraveled, occasionally snagged and often retwined together across time to create a tapestry. This tapestry is woven together by the TC with the support, mediation, and guidance of the teacher educator.

Our vision is for TCs to enter the profession with a complex and nuanced ability to think like a teacher who can enact evidence-based practices equitably and with some skill; a passion for learning and growing; and a deep connection to each other, our program, and Peabody College. Each tapestry, based on this vision, shares these features and thus each one represents an image of a well prepared beginning teacher. The details (e.g. color, texture, etc.) within each tapestry and the process of creating each tapestry may vary from one TC to another. Achieving this vision requires coherence (which can’t be assumed to come from the TC) resting in the work of the TE who clearly and explicitly mediates the on-campus and field-based experiences conjointly with the TC.

Context of Study

Mediating the space between on-campus and field-based learning contexts is challenging for the TE navigating the nebulous and often lamented space commonly referred to as the theory-practice divide (Flessner, 2012; Korthagen, 2007). Gravett (2012) argued that the pervasiveness of the theory-practice divide is an artifact of the design of teacher education programs. She described the prevailing approach in teacher education as a translation of theory to practice approach where the discourse of studying theory from books and lectures in the college classroom runs parallel to the practical application of that theory in the real world of the classroom. This description is consistent with Feiman-Nemser & Remillard (1996) who claim that teacher preparation programs often assume that learning to teach is a two-step process; knowledge acquisition and then application or transfer. Further, Lampert and Ball (1998) describe teacher education as, “a mix of formal knowledge and first-hand experience, theory, and practice divided both physically and conceptually” (p. 25). That the characterization of the theory-practice divide has changed little over time demonstrates the persistence of this gap in teacher education.

If the source of the theory practice divide is rooted in the structure of teacher education, then eradicating this gap requires a reexamination of the structure of teacher education. Attention has shifted to focus on designing practice-based teacher education (Forzani, 2014; Janssen, et al., 2015; Kazemi, et al., 2016). These efforts focus on developing the pedagogical practices of TCs, that are grounded in theory and considered to be high-leverage (Teaching Works, 2020). However, the enactment of teaching practice often remains situated in the college classroom. For example, Flessner’s (2012) self- study explored how serving as a teacher of elementary school mathematics for 3 months changed his pedagogical practice as a teacher educator. He characterized shifts in his practice as the result of gaining a proximity to practice - immersing himself in the realities of teaching elementary school mathematics and then bringing those experiences back into his teaching of elementary TCs in the college classroom. However, this example perpetuates the physical and conceptual distinction that exists between theory and practice because while there is a greater emphasis on developing practice much of this work is still situated in the college classroom (Gravett, 2012; Lampert & Ball, 1998).

We believe the shift toward practice-based teacher education is warranted and important. However, we find that this approach often assumes the TC needs minimal support in order to effectively translate knowledge into practice (Hughes, 2006). Recent work focused on rehearsals (e.g., Kazemi, et al. 2016) provide an example of how TEs might support TCs as they learn to translate the knowledge and skill developed in the college classroom into teaching practice. In the context of rehearsals, TCs learn about pre-identified high leverage practices, rehearse those practices in the controlled context of the university classroom, and receive feedback from the teacher educator to help the TC refine their practice. The potential mismatch between what is being rehearsed in the college classroom and what is being taught in the context of field placements is potentially problematic for the TC who is left to translate what they are learning in these rehearsals and apply it to their teaching. We view these efforts as moving in the right direction, however, we call attention to the difficult translational work that falls to the teacher candidate. As TEs we should explicitly aid the TC in this process of translation by guiding them to focus on pertinent and generative aspects of a teaching interaction. By helping the TC examine particular dimensions in detail, the TE can introduce, make connections to, or scaffold the TC to applicable theoretical notions (Gravett, 2012). Such an approach creates opportunities where the learning of ideas about teaching (theory) is seamlessly interwoven with experiential (practice) knowledge (Gravett, 2012).

As we grapple with the complexities of our work we conceptualize the idea of a theory-practice edge as being more productive than a divide. The image of a divide separates theory from practice whereas an edge brings theory and practice together. In working with TCs across the theory-practice edge we seek physical and conceptual coherence such that the threads of theory and practice do not merely exist in parallel. For us, coherence requires that the TE and TC weave together the strands of theory and practice such that they do not unravel as TCs are in the process of developing the simultaneous and integrated practice characteristic of effective teachers (Palmeri & Peter, 2019). To do this, we maintain a bifocal perspective (Feiman-Nemser, 2001) where we build upon the fundamental aspects of teaching that are accessible to TCs at the very beginning of (and at any point within) their teacher education program while also supporting them as they actively move toward the complexity and nuance needed for real-time teaching. Self-study methodology, focused explicitly on transformation, facilitated our quest for coherence (LaBoskey, 2004)

Aims of the Study

From earlier work, we identified four superordinate elements of teaching (SET) where each element reflected a critical part of teaching that could be explored in isolation and yet also kept a TC focused on teaching as an integrated practice (Palmeri & Peter, 2019). The SET serves as a framework, elegant in both its simplicity and complexity, that create the foundational warp and weft threads of the tapestry being constructed. We undertook this self-study to uncover aspects of our practice that mediated the TCs’ weaving together of the twining threads of theory and practice. We address the question: How does the self-study of our teacher educational practices across the theory-practice edge provide the possibility for clarity and coherence in our work?

Methods

Self-study as a methodology supports work grounded in descriptions of practice, focused on transformation of that practice, and draws upon a variety of qualitative methods (LaBoskey, 2004). This methodology lends both rigor and flexibility to those who question and explore the degree to which their practice makes a difference in students’ learning (Berry and Forgasz, 2018).

Our self-study started 10 years ago when we began sharing our teacher educational stories and practices with each other. At that time we were questioning the coherence between two of our courses that included a field experience. Over time our collaborative self-study became more focused and intentional as it also became more far reaching. We recognized that the search for coherence was moving us beyond our individual courses to the broader scope of TCs’ development within and across our teacher education program. The work presented here draws on data that we began collecting 2 years ago. The primary data sources include: 1) shared interactive self-study notes; 2) analytic notes generated during biweekly conversations; and 3) artifacts of practice that emerged as a result of our changing practice.

Shared self-study notes were collected across these two years in a Google document where we framed our individual reflections around two particular questions: 1) How does what I did today reflect what I know and what I am learning about TC learning? and 2) How does “this” inform how I conceptualize my work as a teacher educator? Each week we individually documented reflections on our teaching and would then read and post comments on each others’ reflections. Later reflections and comments often considered prior reflections and incorporated relevant insights from interactions with students and colleagues. We posed questions, made connections across our reflections, and wondered together about the reflections in light of our guiding questions.

Across these two years, we met biweekly to discuss our individual self-study reflections and the comments and questions we made in response. During these meetings, we delved more deeply into our individual responses focusing on the connections, patterns, or questions that emerged as we read and responded to each others’ reflections in light of our own. We captured these initial analyses in a Google document that was separate from the one where we kept our individual self-study reflections. As we dedicated this time to processing our notes together and making sense of them we found Bogdan and Biklen’s (1997) practice of concentrated time to be critical to moving the work forward. During these meetings we utilized the constant comparative method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990) to look back at the comments we made on each other’s entries and noted patterns emerging in the data.

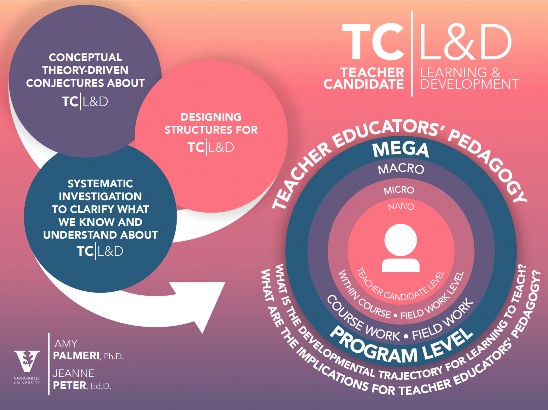

Finally, following this shared analysis we created a visual representation of our work focused on TC learning and development (see Figure 1). This representation provided a means by which we could make sense of emerging patterns and begin to identify connections and relationships between those emerging patterns (Novak & Gowin,1984). In addition, the representation helped us clarify and represent patterns as a conceptual whole. Like Vanassche and Kelchtermans (2015) we found that our self-study work operated at different grain sizes. The visual representation helped us clarify patterns emerging in and across these different grain sizes.

Analysis was organic, on-going, and directly linked to our data collection. As Samaras (2010) explains, we were “in essence generating a working theory grounded in the data of [our] practice and attempting to make meaning of it” (p. 209).

Outcomes

In our ongoing quest to bring coherence to our individual work and the early childhood & elementary education (ECEE) program more broadly, three patterns emerged from our analysis.

The first was categorized at the micro level because it was situated within a course or field experience. A second pattern fell at the macro level because it was operationalized across courses and field experiences. The third pattern was situated at the mega level cutting across all courses in the ECEE program. Identifying these patterns helped us better understand the nature of our work as TEs teaching at and across the theory-practice edge.

Figure 1

Teacher Candidate Learning & Development Framework

Outcome 1: Modeling of Our Own Practice

Our analysis revealed a pattern of our deep commitment to assuring that our pedagogical practices across teaching contexts were consistent with the practices we expect our candidates to learn and enact. A focus on modeling was pervasive in our shared analysis notes:

What we saw this week is that we are modeling for our own students (AP talked about her teaching with the photograph exercise) what we want [TCs] to understand for their own teaching. We are modeling for our University Mentors as we share in our monthly meetings and learn from each other. JP is modeling how to think reflectively and make connections as she provides reflective prompts and responds to TCs... AP’s modeling with the photographs did not come as “first, you provide students with a set of photographs. Next ” rather AP allowed TCs to experience something through her modeling and then she brought it to a moment of coherence by connecting it to the learning goal. (Oct. 1, 2019: Shared Analysis)

This quote illustrates our commitment to modeling research-based practices for TCs through our pedagogy. It is significant that by modeling here we are not doing with TCs things that directly apply to their work in the field (e.g. it is not we do this in methods and now you go do the same thing in the field with children). We are modeling strategies in our teaching to support TC learning rather than mimicking what TCs will do in their work with children. As part of our teaching, together with the TC, we tease apart the what, why, and how of our decisions and the learning experiences the TCs engage in as a way to generate meaningful parallels to their work in the field. When we notice our TCs are not taking up research-based practices we stop to ask ourselves “why”, assuming that if we are not seeing what we expected then our pedagogy needs to change.

For example, in the context of the science and social studies practicum, Amy created a weekly seminar where TCs rehearse portions of their planned lesson to be implemented later in the week. Informed by our earlier critique regarding rehearsals, Amy has TCs rehearse a universal part (rather than a particular practice) such as the lesson launch. This allows TCs to rehearse a part of a lesson that they would teach two days later. Across two seminars focused on the lesson launch, 8 TCs rehearsed their launch and received feedback. Each seminar closed with a discussion to enhance TC's understanding of the importance of the launch. The first posed the questions: 1) what purpose does a lesson launch serve? and 2) what are the features of an effective lesson launch? The second seminar asked: 1) What range of instructional strategies did you utilize in your lesson launches? and 2) What other strategies could we use? Through these discussions, the theoretical idea of lesson launches introduced in methods courses were made concrete in practicum seminar, and rather than reifying one “right” approach to a lesson launch the rehearsals broadened the TCs’ initial repertoire for lesson launch strategies. Thus, seminar discussions, in conjunction with rehearsals, provided threads that helped us straddle the theory- practice edge.

Outcome 2: Sustaining Feedback

Secondly, a pattern of sustaining feedback, the process of pressing on each other through repeated analysis and reflection (allowing us to envision practice in a way we would not have independently) emerged (Cole, 2006). Sustaining feedback enables us to make ongoing adjustments to our practice while keeping focused on our goal of clarity and coherence. This example illustrates our sense of how theory and practice are intertwined.

What are the things that we must do to create a solid beginning teacher? How do we think about our work in terms of a threshold that is good enough? We can’t yet determine which of the myriad of things we are doing makes the most difference [in terms of TC learning and development]. What are the things that add value and what are the things that are good but don’t add significant value? What is the right balance of this and the “dosage”-- how frequently TCs need it? (October 1, 2019: Shared Analysis)

Here we focus on the TC as we ask what it means to create a solid beginning teacher. This question is both about end point and starting point. Considering our vision of a well- prepared teacher, where do we begin? The question of where we begin has direct implications for what we are doing in our respective courses and field experiences because they are taken in a particular sequence. As a result, we began creating developmental benchmarks in Jeanne’s initial literacy course where TCs are tutoring a single child. Developing expectations established a beginning point that Amy would build upon in her practicum. The following example reflects one of the behaviors Jeanne began tracking at the beginning, midpoint, and end of her embedded practicum.

|

Emergent Teacher Language

|

Proficient Teacher Language

|

End of Course Teacher Language

|

|

The TC is doing most of the talking and intellectual work. The student often seems confused by the TCs prompts/questions.

The TC’s language is inappropriately above/below the student’s zone of proximal development.

|

The TC’s language provides the opportunity for the student to do the majority of the intellectual work, scaffolding and prompting student language and thinking in order to support growth toward skilled, strategic and independent reading and writing.

The TC attempts rich language and is aware of the student’s zpd and background knowledge as evidenced by attempts to make adjustments.

|

The TC provides clear, concise, explicit, useful, responsive, encouraging, supportive, and appropriately timed prompts/questions/ statements and connections to student assets and background knowledge that support the student toward skilled, strategic, and independent reading, writing, and thinking. The TC uses rich language that is right in the student’s zpd and connects to/builds upon student’s experiences and prior knowledge.

|

These benchmarks, which we continue to revise and refine, force us to pay close attention to the development of our TCs within and across fieldwork. In our ongoing shared analysis, we press each other to support emerging conjectures regarding TC development. Without the sustaining nature of this feedback to each other, we would be less explicit with TCs and less explicit in our ability to create coherence between field experiences.

Outcome 3: Adding Depth to Our Work

Finally, coming to understand the overlapping grain sizes of our work as TEs adds depth to our practice. These elements are grounded in the superordinate elements of teaching (SET).

The SET - teacher language, subject matter, student engagement, and lesson flow - give us a way to organize and describe our work as TEs in simple terms that communicate to TCs the main elements of teaching. At the same time, the SET provide a robust opportunity to delve into the nuance of teaching with greater specificity and complexity. The SET represent four additional interwoven threads that together with the twined strands of theory and practice are woven into the tapestry. Through self-study we identify opportunities that capture the complexity of these interdependent relationships serving to bring coherence to our work as teacher educators. For example:

As we’ve noticed the ripples and considered that “every interaction is a teaching moment” and while we know that this is an important place to be as a TE and as we theorize about teacher education, it isn’t sustainable. So how do we balance the micro and macro issues that come into play here?

-

We agree that emails are a teaching space and this should be our default stance (nano level)

-

Feedback on assignments - which aligns with the focus on feedback in the post-observation conference seems another fruitful teaching moment.

-

We need to get on the student interviews so that we can see what the TCs find instructional. At what point does feedback become overkill - both for us as TEs and for the students as TCs? (April 22, 2019: Shared Analysis)

The SET and the Teacher Candidate Learning and Development Framework (see Figure 1) provide us with a way of examining our work in greater depth and nuance and also scaffolds our ability to think along and across grain size. For example, we realized that we did not have insight into individual TC’s perceptions of our feedback on lesson plans. As a result of this insight, we designed a Google form (sent to TCs after receiving feedback on a lesson plan) to identify what lesson plan feedback they took up (if any) as they reflected on, reviewed, rethought, or revised their lesson plan prior to teaching.

Toggling back and forth across grain sizes (within our individual courses to those parts of our work that rippled out to impact the entire program) provided us with an opportunity to make intentional decisions about our pedagogical practices and the direction of our work. Creating a visual representation (see Figure 1), emerging from our self-study analysis, provided us a way to look across our work to identify where our work was or was not coherent. The representation allowed us to keep our heads wrapped around the whole of our work and also supported our ability to visualize individual practices that held the greatest potential to positively contribute to the whole. With this framework, we were able to move toward greater coherence instead of potentially becoming stagnated at the level of individual pedagogical improvement.

Conclusion

We are challenged, when teaching a complex practice like teaching, to pull the threads of TCs’ developing practice into the university context as we are also pulling the threads of TCs’ nascent understanding of theory into the P-5 context. We believe that at the nexus of this challenge is coherence which we define as making explicit the holding together of theory and practice. As Darling Hammond (2020) said, “You learn everything is connected. So, if you pull on one string in a tapestry, you get a tangle. What you really need to do is think about the whole piece and how you’re going to move all the parts in a direction of greater opportunity.” In this study we sought to answer the question: How does the self-study of our teacher educational practices across the theory-practice edge provide the possibility for clarity and coherence in our work? We claim that this can best be done by teacher educators who relentlessly study their own teaching, using this ongoing analysis to intentionally design program structures and teacher education practices, honing the theory-practice edge, and thereby enabling TCs to bring theory into practice AND practice into theory.

References

Berry, A., & Forgasz, R. (2018). Not-so-secret stories: Reshaping the teacher education professional knowledge landscape through self-study. In. D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-Study as a means for researching pedagogy (pp. 43-50). Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. K. (1997). Qualitative research for education. Allyn & Bacon.

Cole, A. D. (2006). Scaffolding beginning readers: Micro and macro cues teachers use during student oral reading. Reading Teacher, 59(5) 450-459. https://doi.org/10.1598/RT.59.5.4

Darling-Hammond, L. (2020, April 6). COVID-19 brings ‘central importance of public education back to peoples minds’. Educationdive. https://edtechbooks.org/-oDNGwww.educationdive.com/news/darling-hammond-covid-19-brings-central- importance-of-public-education-ba/575396/

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). Helping novices learn to teach: Lessons from an exemplary support teacher. Journal of Teacher Education, 52(1), 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487101052001003

Feiman-Nemser, S. & Remillard, J. (1996). Perspectives on learning to teach. In F. Murray (Ed.), The Teacher Educators’ Handbook (pp. 63-91). Jossey-Bass.

Flessner, R. (2012). Addressing the research/practice divide in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 34, 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.677739

Forzani, F. M. (2014). Understanding “core practices” and “practice-based” teacher education: Learning from the past. Journal of Teacher Education, 65(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487114533800

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Weidenfield & Nicolson. Gravett, S. (2012). Crossing the “theory-practice divide”: Learning to be(come) a teacher. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 2(2), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v2i2.9 Hughes, J. A. (2006). Bridging the theory-practice divide: A creative approach to effective teacher preparation. Journal of Scholarship and Teaching, 6(1), 110-117.

Janssen, F., Grossman, P., & Westbroek, H. (2015). Facilitating decomposition and recomposition in practice-based teacher education: The power of modularity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 51, 137-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.06.009

Kazemi, E., Ghousseini, H., Cunard, A., & Turrou, A. C. (2016). Getting inside rehearsals: Insights from teacher educators to support work on complex practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 18-31. DOI: 10.1177/0022487115615191

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2007). The gap between research and practice revisited. Educational Research and Evaluation, 13(3), 303-310. https://doi.org/10.1080/

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817-869). Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6545-3

Lampert, M. (2010). Learning teaching in, from, and for Practice: What do we mean? Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347321

Lampert, M., & Ball, D. L. (1998). Teaching, multimedia, and mathematics: Investigations of real practice. The Practitioner Inquiry Series. Teachers College Press.

Langdon, F., & Ward, L. (2015). Educative mentoring: A way forward. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-03-2015-0006

Novak, J. D., & Gowin, D. B. (1984). Learning how to learn. Cambridge University Press.

Palmeri, A. B., & Peter, J. A. (2019). Pivoting from evaluative to educative feedback during post-observation conferencing: Supporting the development of preservice teachers. In Handbook of Research on Field-Based Teacher Education (pp. 495-517). IGI Global.

Samaras, A. P. (2010). Self-Study teacher research: Improving your practice through collaborative inquiry. Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

Teaching Works. (2020). High leverage practices. http://www.teachingworks.org/work-of- teaching/high-leverage-practices

Vanassche, E., & Kelchtermans, G. (2015). The state of the art in self-study of teacher education practices: A systematic literature review. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47(4), 508-528. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2014.995712