We were already friends and enjoyed engaging in opportunities to challenge one another’s thinking. During a conference several years ago, such a moment arose and we both tugged from different directions. It started with a little debate about our identities:

Stephanie: Do you consider yourself an art teacher?

Bill: No, I haven’t taught art for a long time. I’m a teacher teacher. So are you.

Stephanie: Yes, but I’m still an art teacher.

Bill: But you don’t teach art anymore. You teach others how to be good art teachers. That’s entirely different.

The discussion continued, back and forth in this manner, until we decided it was something we should investigate further. We knew we wanted to collaborate rather than simply give one another feedback on individual searching.

We are currently situated in higher education programs in which we are responsible for teaching and improving art education methodology courses for future art teachers. Our classes are relatively small and provide us both ample leeway in the design and implementation of the curricula. As we continued to lead our pre-service students through the critical development of their teaching identities (Ramirez & Allen, 2018), we thought it critical that we were not only familiar with and confident in the origins of our own but that we were also in the practice of understanding our selves through and with our work as educators and artists. We wanted to model collaboration and the generative nature of exploring self alongside other, similar to how Allison and Ramirez (2016) described co-mentoring. “We were positioning ourselves as co-mentors in a reciprocal partnership, mentoring each other as we faced similar challenges and responsibilities” (p. 6). This extended the more traditional notion of critical friends or “executive coaching” (Loughran & Allen, 2014) where instead of only seeking feedback from an external, trusted scholar, we were interested in the potential synthesis offered through collaboration.

Stephanie had been using Pinar’s (1975; 1994) currere method with her undergraduate teacher education students to help them identify and develop personal, meaningful stories of self- empowerment and professional identity (Baer, 2017). She introduced Bill to the methodology and after some deliberation, he was convinced it might shed light on their identity debate. We began following Pinar’s four steps for examining our own educative journeys through regression, progression, analysis, and synthesis (Pinar, 1975). Throughout our investigation of the methodology, we worked together in a manner that surpassed critical friendship and allowed us to perform a self-study that capitalized on our strengths of collaboration, storytelling, and art-making to critically evaluate our data.

The image in Figure 1 astutely illustrates our notion of critical collaborators. Instead of engaging with the current steps on our own and then coming together at the end to discuss it, we approached new understandings of our diverse backgrounds together. Like the tree trunks pictured above, our collaboration created a stronger and more authentic awareness of the journeys we had taken and enabled us both to look forward with confidence. Our personal narratives and artworks were offered up in weekly meetings with an invitation to be questioned, critiqued, and clarified. Awareness of one another’s consistent and sometimes divergent, perspectives necessitated a constant re-situation of identity, motivation, and purpose. In order to effectively collaborate, we had to be open to questioning our assumptions of identity through open conversations about what our intentions were and how those assumptions informed our identity development. Why was Stephanie so centered on being called an art teacher? Why was Bill so averse to being labeled an artist? What might that mean for the students in our classrooms?

Figure 1

Growing Together. Color photograph, 2019. Photo credit: Stephanie

Regardless of how or why it started, both trees were continuing to grow with one another. They had their own paths but were both absolutely intertwined, determined by, and dependent on the support of the other. They were both stronger because they were growing together.

Aim / Objectives

The problem that we have come together to consider is one of identity as educators, researchers, and artists. How can we be all of those things and—if we can be all of them—how do we weave them together and is any one component more important than another?

Understanding the intricacies of the multithreaded tapestries of our identities required critical collaboration that went beyond the benefits gained through a traditional critical friendship.

Individually, we had reflected in limited ways (e.g. talking with family and friends outside our discipline, journaling, etc.). We wanted to identify individual and shared goals, consider new ways of knowing our mutual and diverging paths, and utilize methods in tandem with one another.

Despite the disparities of our backgrounds, we both grew up with an appreciation for the arts, moved into the field of art education, and chose to be postsecondary teacher educators to help improve the field as a whole. However, the differences in how we originally understood our roles as art teachers or teaching artists persisted as an impetus for conversation and debate between us for a long period. Knowing this about ourselves became vital to how we approached and encouraged our students and the development of their teacher identities. It was this dichotomy between our self-perceptions as artist-teacher and teaching-artist that pushed us into the realm of self-study and critical collaboration. Our ultimate goal is to develop and refine this method of critical collaboration to benefit any teacher to better understand themselves as an educator and maker. This paper serves as an illustration of critical collaboration and its impact on professional and personal identities linked to teaching practices.

Methods

The natural evolution of our critical collaboration borrows from currere method and self-study, necessitating a weaving together of ideas. Each approach offers a unique perspective on how critical friends might evolve into critical collaborators. This phenomenological qualitative research addresses our “conscious experience of [our] life-world” (Merriam, 2009, p. 25), and our identities as artists, art educators, and teacher educators. Our methodology for conducting the study is rooted both in Pinar’s (1975; 1994) currere method of self-study in which we explored the phenomenon of professional identity as well as Russell’s (2005) notion of critical friendship. In Pinar’s (1975) regressive step, we worked through personal histories, collaborator interviews, and recorded conversations to elucidate the assumptions we had about the impact of our pasts. In the progressive step, we considered our futures as educators and artists with written narratives and recorded conversations and projected the influence that our current identities had on our long and short-term goals. Now, in the analytic step, we create and collect artwork, organize, and discuss the copious amount of data that we have been collecting for years regarding our identities.

Weekly online conferences allowed us to meet “face to face” and recording our conversations made it possible for us to revisit those discussions. Using personal narratives, informal interviews of one another, as well as collecting and creating artifacts like artwork, course assignments, personal and professional mantras and videos of our teaching, we uncovered (and are continuing to uncover) incredible insights about ourselves, our identities and their evolutions, motivations, goals, and teaching practices.

Next, we fine-tuned our phenomenological study with Zeichner’s (2007) introspection on self-study:

I believe that self-study research can maintain this important role in opening up new ways of understanding teacher education and of highlighting the significance of contexts and persons to inquiry while joining the discussions and debates about issues of importance to teacher educators, policy makers, and those who do research about teacher education. (Bullough & Pinnegar, 2001; Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Zeichner, 2007, p. 42)

As Zeichner and others suggested, we developed a new way to create, collect, and analyze data through critical collaboration. We used this methodology to get to the root of issues that all educators face, those of identity and purpose as they are tied to the profession. The importance of facing similar challenges, examining self through others, and identifying ways to improve our own teaching practices can not be overstated.

Additionally, we paid close attention to Moustaka’s (1994) horizontalization process for collecting and examining phenomenological data in which every piece of data is initially given equal weight and then broken down into themes. Moustaka’s process is particularly poignant to us as an “interweaving of person, conscious experience, and phenomenon” (p. 96). Through which, “...every perception is granted equal value, nonrepetitive constituents of experience are linked thematically, and a full description is derived” (p. 96). For further measure, we tempered our research with Schuck and Russell’s (2005) explanations of critical friendship. They describe the difficulty of conducting self-study and the important role that critical friendship should play in it. Although we expanded the notion of critical friendship into a more specific and appropriate term for our own research, critical collaborator, we adopted it from their definition of critical friendship as someone who “acts as a sounding board, asks challenging questions, supports reframing of events, and joins in the professional learning experience” (p. 107).

Critical collaborators, however, do more. The longer we have worked together, the more it has affected our work. For instance, this article is not merely a summation of the thoughts, actions, and research of two people, it is a fusion of those things. We work on this paper at the same time and separately, add and subtract from each others’ written work, and constantly question word choices, references, and ideas. By going through the currere process in this same manner, we have grown to respect, appreciate, and depend on the other’s feedback and point of view. Now, in the analytic phase, we have come to a similar place in which we unabashedly critique and question the other’s work in an effort to make it as clear and meaningful as possible. The interwoven collaboration that we have developed through this process is a powerful tool that we intend to now share with our own students.

Outcomes

With each phase of the currere process (Pinar, 1975; 1994), we exposed, clarified, and complicated our identities. We noticed deep-seated assumptions we had about ourselves and the other, and found thoughtful ways to reflect on our collected data and continuing conversations. Though we did not arrive at concrete results or identity labels, we did develop a clearer understanding of how we got here. We more deeply appreciated the complexity of our teaching methodologies and educative goals. That awareness gave us the power to be more purposeful in our teaching and how we lead students to develop their own identities. Through the currere and collaborative processes, we have found our individual paths crossing more and more frequently and that they are now imbued with much more understanding and rationale. We have given ourselves the freedom to explore the fabric of our personal and professional identities and each takes solace in knowing that there is another navigating the same tapestry. Below are some insights into that exploration, owed to the critical friendship turned critical collaboration.

Figure 2

She Who is an Artist. 2001. Artwork by Suzy Toronto

Stephanie

There is an image that has hung in my space since I was a young art student (see Figure 2). My sister and brother-in-law gave it to me and it was perfect. That identity was solidified and reified often for me growing up, so much so that I majored in fine art in college without ever questioning the decision. As I have grown and evolved into the artist and teacher I am today, I have come to understand that image differently. Bill helped me identify the foundation that had been built early on and what led my assumptions about the innate need for art and making. Having taught art as a job rather than a calling earlier in his life, he encouraged me to unpack why being called an artist and why calling my students artists was so important to me. It was my foundation for knowing myself and what I had to offer the world. I was failing to put as much weight on the more recent identity developments I was experiencing as a teacher and teacher educator. I was glossing over how my most current courses had developed into exercises in confidence-building through visual means. I was using art and creativity as a way to help students see themselves more clearly. Exploring my past, learning about Bill’s past, and discussing what we dreamed for our students helped me clarify why and how I taught.

The shift was in how and where my identity has rested and had meaning. I previously borrowed others’ confidence that I was where and who I should be, and now I understand my artist self to be a structure that holds the way I view the world. It is a comfortable home for when I venture into the uncertain territory of teaching and learning. It offers a vehicle for making meaning and creating pathways for communication, seeing, and empowering learners.

Bill and I explored our current artist selves more intentionally. I intended to offer up images of what I was creating in a letterpress class I enrolled in. However, I found myself ruminating on photographs I was taking throughout the day. I was searching for a way to express and understand my current academic life (see Figures 3–5) while in conversation with Bill.

Figure 3

My Courage Always RISES. Letterpress form, 2019. Photo credit: Stephanie

Quotes from other artists often provide the necessary insight to explain your own situation. Finding the right type and design to illustrate Jane Austen’s ideas about courage and resilience was an exercise in owning the words myself. Many of the conversations between Bill and I had been about self-actualization, so it was at the forefront of my mind as I gathered images. The insight gained through reflection on the images with Bill offered another layer to how I was able to see and understand my context as a teacher educator and how that influenced my perspective and choices throughout the day.

Figure 4

No Stopping Any Time. Color photograph, 2019. Photo credit: Stephanie

On an evening walk with my 8-year-old daughter, we paused at the end of a street marveling at the clouds and fading light. She looked up at the sign she was leaning against and asked, “Why can’t we stop?” She had a pleading look in her eyes as she motioned out to the open space we’d been staring at. “It’s okay,” I said, “Just enjoy it.” This was reflected in the conversations Bill and I had asked one another, like; “Why don’t we stop? What is it about the daily sandstorm we all seem to create for ourselves that pulls us so far from these moments?

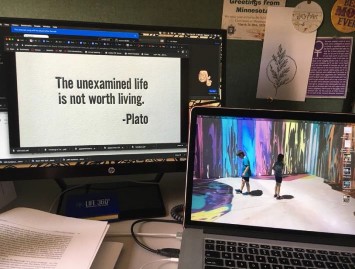

Figure 5

Examining Life. Color photograph, 2019. Photo credit: Stephanie

Interesting juxtapositions present themselves and often need to be documented. The moment captured in Figure 5 offered an interesting glance at the whole of work and life, teaching and parenting, ideas and spaces. With each photograph I shared with Bill, layers of meaning unfolded. What would begin as a seemingly simple moment of capturing beauty, creating an interesting composition, or noticing some natural irony, became an exercise in how Twyla Tharp (2004) described creative habit:

Creativity is more about taking the facts, fictions, and feelings we store away and finding new ways to connect them...Metaphor is the lifeblood of all art, if it is not art itself. Metaphor is our vocabulary for connecting what we’re experiencing now with what we have experienced before. It’s not only how we express what we remember, it’s how we interpret it—for ourselves and others. (p. 64)

Bill looked at my images each week and asked me questions like, “Why did you choose that one?” “What’s beautiful to you about that?” “What does this one mean?” “Why that angle?” He gave me his perspective and we made connections between his artwork as well. We questioned the emotions and ideas behind them. My responses were not always ready or eloquent but allowed me to question the decisions I was making and see my and his perspectives with more complexity. My images became deeper metaphors for how I was seeing and experiencing the world, my work, and my personal life. Just as my identities were inextricably woven into one another, my meaning-making with photographs became a composition of threads from all aspects of my life. I was more fully understanding how the decisions I was making in one area would tug and loosen threads connecting to other areas.

In exploring my past artist identity and the hold it had on me (Cavill & Baer, 2019), I was able to re-examine the role it played in my worldview—as a teacher educator interested in using art as a vehicle, rather than a content area. I wanted my students to experience the creative process, but not be limited by its labels.

Bill

As a public school art teacher, I never thought of myself as an actual artist. I discovered this about myself through the conversations that Stephanie and I had in the early stages of the currere process. Even when I was teaching others how to make art, to relate to the world through art, and to see as artists saw, I did not believe that I was an artist. I often found myself saying things like, “I don’t make art, I make examples.” I believed that art was something reserved for those who had made careers out of it. In my mind, I had traded being an art maker for being a teacher. How could one be both? So, when I made images they were for instructional purposes; I thought about the elements and principles and how the piece could be used to demonstrate those. The work took on a purely functional quality.

Figure 6

Don’t Touch That. Ink and colored pencil, 2010. Photo Credit: Bill

Figure 6 is a piece that I made to share with public school students as an example of the use of line, value, shape, repetition, and balance in a composition. At the time, I did not appreciate it as a work of art in and of itself. As Stephanie and I collaborated over months and years, I began to understand that I was not seeing the entire picture. I had focused so hard and for so long on the teaching aspect of my career that I had neglected the artistic. Through our dialogue, I began to accept the possibility that I might, in fact, be an artist. It did not happen in a moment. There were no angels singing and no glorious lights from on high. It was a slow and arduous revelation. I was reluctant to accept this new component of my identity because I did not believe I had time for it, was qualified for it, or have it be accepted by my artmaking peers.

When Stephanie and I began the analytic step in the currere process, we realized that artwork would be an important kind of data to collect. I was reluctant to share my artwork, but Stephanie encouraged and assured me that it would prove enlightening. Shortly after that conversation, I found myself doodling during a faculty meeting (see Figure 7). When I looked at that image through the analytic lens that Stephanie and the currere process had helped me acquire, I saw it as more than a doodle. It was a snapshot of my life at that moment; a visual expository of the meeting that demonstrated my frustration at the futility of such meetings. I realized that I was making art. Once I began to think of those drawings as art, I fell in love with the artmaking process and results. Moreover, I found myself better engaged in meetings than I had been before, paying attention to what was said, how it was said, and what was left unsaid. I recall being excited and anxious to share that drawing with Stephanie; would she validate it as art or confirm my inner doubts about its artistic quality? She validated it, and I was soon sharing my pieces gladly, even proudly, every time I made one.

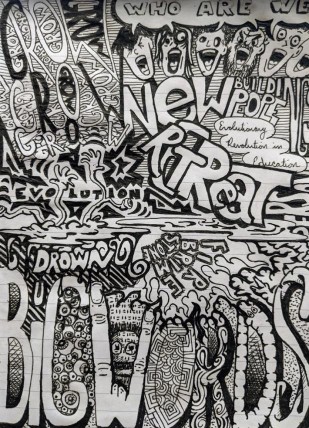

Figure 7

Retreat. Ink, 2019. Photo Credit: Bill

Figure 7 was based on a college-wide faculty meeting that lasted for hours and was filled with vague promises and awkward silences. After conversing with Stephanie about the piece, it became the first of a long series of drawings I made based on the common things in my life. I created one at a board meeting for a non-profit organization (see Figure 8), another during a State Conference session (see Figure 9) and always through university meetings (see Figure 10). Being willing to share these images at all was a testament to the critical collaboration that Stephanie and I had been through. When I began this process, I thought so little of my own artistic abilities that I would have been embarrassed to share them. Having gone through this self-study, I was able to view my work through someone else’s eyes and finally appreciate its value as art.

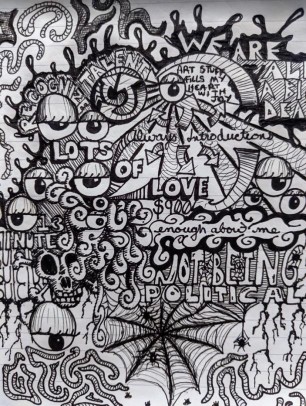

Figure 8

LoL. Ink, 2019. Photo Credit: Bill

Figure 9

Be Kind. Ink, 2019. Photo Credit: Bill.

During our critical collaboration, Stephanie and I would often share our frustrations, concerns, successes, and excitement about what was going on in our various institutions. One thing we occasionally shared was how inconsequential many of the meetings we found ourselves in were. Sharing these experiences taught us both to question the agenda behind the agendas and consider the true purposes for the meetings. Looking at these pieces reminds me of all the topics that were covered during conference sessions and faculty meetings. Stephanie and I were able to relate these experiences directly to our own professional lives and the similar problems we faced as they poured down on us like sand in a sandstorm (Baer & Cavill, 2020).

Figure 10

Little Mess. Ink, 2019. Photo Credit: Bill

Occasionally, faculty meetings get messy. In this particular meeting (See Figure 10) several departmental facts were revealed to attendees that caused stress and frustration. Keeping this visual record helped me to collect my thoughts, keep my cool, and consider my reactions.

This related well to the conversations that Stephanie and I had regarding our own students and classrooms. This image caused us both to talk about how our own students might become overwhelmed when we surprised them with new content or requirements.

The reflective power of the images we have created, and the critically collaborative consideration we have given them, may make it necessary for us both to change how we teach future art teachers. While the details of those changes will be the content of the next step of currere, analytical, we understand now the powerful tool inherent in self-study through critical collaboration.

Moving Forward

As critical collaborators, we have offered one another the space and time necessary to ask fundamental questions about ourselves. The threads of our identities have shown their true colors and become stronger because of their connections with one another. We understand critical collaboration to require vulnerability, thick skin, openness, perseverance, time, friendship and compassion, patience and flexibility, coworking, and a true interest in another’s experiences and growth.

As we move forward through the analytical to the synthetical within the currere process, investigating ourselves as teacher educators and critical collaborators, we are making the assumption that good leaders know themselves well and because of that, are more reflective, empathetic, adaptive to change, and able to create productive change. We connected these ideas of knowing one’s self to our ability to see others better and more readily with empathy and care. We anticipate that the results of this continuing study will provide us with a clear and authentic definition and description of critical collaborators that can be used to help ourselves and other educators develop a deeper knowledge of what it means to be a teacher, researcher, and artist.

References

Allison, V. A. & Ramirez, L. A. (2016). Co-mentoring: The iterative process of learning about self and “becoming” leaders. Studying Teacher Education, 12(1), 3-19.

Baer, S. (2017). ARTed Talks: Promoting the Voices of a New Generation of Art Teachers. Art Education, 70(4), 29–32.

Baer, S., & Cavill, W. (2020). Seeing through the Sandstorm: Envisioning a future through critical friendship and alongside the present. The Currere Exchange, 3(2), 57–65.

Bullough, R. V. & Pinnegar, S. (2001). Guidelines for quality in autobiographical forms of self- study research. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 13–21.

Cavill, W. & Baer, S. (2019). Exploring the process of becoming art teacher educators through collaborative regression. The Currere Exchange, 3(1), 95–104.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. Jossey-Bass.

Loughran, J. J., & Allen, M. (2014). Learning to be coached: How a dean learnt with a critical friend. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.), Changing practices for changing times: Past, present and future possibilities for self-study research (Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Self Study of Teacher Education Practices, pp. 139–141). University of Auckland.

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey Bass.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological Research Methods. Sage.

Pinar, W. F. (1994). Autobiography, politics and sexuality: Essays in curriculum theory 1972– 1992. Peter Lang.

Pinar, W. F. (1975) The Method of “Currere.” Annual Meeting of the American Education Research Association. Washington D.C

Ramirez, L. A., & Allison, V. A. (2018). Examining attitudes and beliefs about public education through co-autobiographical self-study. In D. Garbett & A. Ovens (Eds.). Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for researching pedagogy, S-STEP, ISBN: 978-0-473-44471-6, 351.

Schuck, S., & Russel, T. (2005). Self-study, critical friendship, and the complexities of teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 1(2), 107–121.

Tharp, T. (2004). The creative habit. Simon & Schuster.

Zeichner, K. (2007). Accumulating knowledge across self-studies in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 36–46.