In recent years, there has been recognition of the overlapping, multiple, and entangled identities that concern artists, teachers, and researchers in the visual arts (Daichendt, 2010; Thornton, 2013). As Wilber (1997) explained: to understand the whole, it is necessary to understand the parts. To understand the parts, it is necessary to understand the whole, repeating to create a circle of understanding (Wilber, 1997). References to artists, teachers, researchers are not just descriptions of roles or practices but a way of being that integrates “theory and practice in the interest of good practice” (Thornton, 2013, p. 8). Artist-teacher-researchers recognize that “in our everyday lives we are involved in some form of inquiry, in a search for information” (Miraglia, 2014, p. 8) which in turn shapes our personal and professional identities.

The study of teacher identity requires reflection upon self (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009) from multiple paths and over time, as identities are not fixed, but are constructed and reconstructed throughout a lifetime (Erikson, 1980; Knowles, 1980). The basic need to create and more fully understand art as a means of inquiry can shape pedagogical choices and transform both the individual (teacher) and the collective (students/class) is at the nexus of our research.

The arts foster engagement in the deep work of identity construction, of uncovering “the self who teaches” (Palmer, 1998, p. 7) and becomes the connecting thread that weaves together the roles of artist-teacher-researcher. This study focuses on the teacher educator’s experiences as artist-teacher-researchers and how these roles shape identity construction through an engagement of on-going studio practice.

Context of the Study

In this self-study, three American female artists and teacher educators who identify themselves as artist-teacher-researchers seek to explore the balance between studio practice, teaching, and research. These authors currently teach preservice and in-service art education students in university settings, having had extensive previous experience teaching in elementary and secondary settings. Research indicates that the lack of synergy between artistic studio practice, teaching pedagogy and research of visual arts educators has been a challenge in the field of arts education (Strickland 2019; Walker 2013). Thornton (2013) suggested that examining the identity of the artist-teacher-researcher could help to understand the complicated and intertwined identities of art education practitioners. Reflecting on one’s practice is integral to identity formation on all levels and can be used in the assessment of those practices (Schon, 1987). Furthermore, it is essential that teacher educators explore the ways in which their identities and values play out in the classroom, recognizing that these choices hold great power and potential to impact our students as future teachers (Buffington & McKay, 2013). Through engaging in this research study, we scrutinized our own identities, shared instances of reflective practice, and moved toward constructing insights into our own teaching.

In this qualitative, arts-based research we aim to explore the following:

-

Why is engaging in a studio practice and making essential to good teaching and researching?

-

How does a collaborative community integrate the threads (making, teaching, researching) that shape our work, both professionally and personally?

-

How do we critically identify and explore the ways in which our identities and related values impact our teaching practice?

Methodology

This qualitative study stems from self-study methodology (LaBoskey, 2004), arts-based research (Sullivan, 2005), and the critical friends model (Louie, et al., 2003). By drawing from multiple forms of data: personal art practice, journals, and discussions, our goal was to better understand the complexities of the artist-teacher-researcher, exploring why engaging in the practice of making is essential to good teaching.

The goal “of self-study research is to provoke, challenge, and illuminate rather than confirm and settle” (Bullough & Pinnegar, 2001, p. 20). Pinnegar and Hamilton (2009) stated that through self-study methods “[w]e seek to make sense of the stream of experience we act within, knowing that our actions generate new relationships, new practices, and new understandings of our reality” (p. ix). Additionally, using art-based research offered another lens as “an embodied living inquiry, an interstitial relational space for creating, teaching, learning, and researching in a constant state of becoming” (Irwin et al., 2006, p.71).

Trustworthiness and validity can be challenging for the arts-based researcher, however, this can be achieved by maintaining and monitoring “a creative and critical perspective so as to be able to document and defend the trustworthiness of interpretations made” (Sullivan, 2006, p. 29). In this study the three visual art educators monitored each other’s progress as critical friends through dialog, critique, and sharing of art works and journal entries. “To create and critique is a research act that is very well suited to arts practitioners, be they artists, teachers or students” (Sullivan 2006, p.20).

Arts-Based Research: Embracing Art Practice as Research

Using an arts-based research methodology in this study highlighted our roles as artists by providing an authentic research perspective as “the arts provide a special way of coming to represent and understand what we know about the world” (Sullivan, 2010, p. 56). As such, “arts- based research is an effort to extend beyond the limiting constraints of discursive communication in order to express meanings that otherwise would be ineffable” (Barone & Eisner, 2012, p. 1).

By employing an arts-based method, we were able to acquire information that did not require positivistic methods or verbal dialogue; therefore, it did not oppose science, but rather, operated in partnership with scientific methods of inquiry (McNiff, 1998).

One of the most enduring themes in science and philosophy is the tension between what can and cannot be known and expressed. …Using creative methods to investigate phenomena provides an aesthetic method of documenting and understanding experiences. Arts-based research does not follow a predetermined standard sequence of steps to arrive at an answer; like art itself, the emergence of answers ultimately comes from embracing the unknown. (McNiff, 1998, p.31)

Employing an arts-based approach allowed us to access, explore, and bring to light various aspects of unconscious, embodied knowledge through artistic images and other forms of artistic works. “The role of lived experience, subjectivity, and memory are seen as agents in knowledge construction and strategies such as self-study, collaborations, and textual critiques and are used to reveal important insights unable to be recovered by more traditional research methods” (Sullivan, 2006, p.24). In order to facilitate new insights and understandings, Sullivan (2005) challenges existing paradigms and adapts visual arts strategies in order to conceptualize theories and practices that are grounded in visual arts practices without being narrow in scope, too prescriptive, and limited in perspective. Where quantitative methods are based on probability and plausibility, arts-based practice is focused on possibilities or the potential of art to foster change, based on its capacity to be individually and culturally transformative.

Arts-based research uncovers “relationships and patterns among and within ideas and images” (Garoian, 2006, p. 111) to explore and discover new theory, and is a process of inquiry that requires creative action and critical reflection. Art practice, in its most elemental form, is an educational act, where the intent is to provoke dialogue and to initiate change in making and teaching art and in researching art practices. Thus, exploring our art practice was a way of knowing ourselves and the way our values were embedded in our practice as artists, teachers, and researchers.

Critical Friends

A critical friend is a trusted person who provides feedback to an individual or groups through critiquing work, offering a different perspective on the data, asking provocative questions, and supporting the success of the overall work (Costa & Kallik, 1993). Engaging in a critical relationship adds to the trustworthiness of the research by clarifying ideas and goals, ensuring specificity, while responding to and assessing the work with integrity (Costa & Kallik, 1993). Forming collaborative groups, known as communities of practice, consisting of critical friends, is an element of self-study research (Louie et al., 2003) and examines “the intersection of issues of community, social practice, meaning, and identity” (Wenger, 2003, p. 4). Communities of practice are formed when people pursue shared experiences, relationships, and multiple perspectives. Participants come with their own understandings and assumptions where identities are defined as lived experience in a social practice. When a community of practice functions well, it becomes a space that is connected to profound and consequential discourse, designed to be a resource for practice and to open up new possibilities (Lave & Wenger, 2003). Through constructive discourse and group inquiry critical friends in a community of practice can test, negotiate, develop and share results (Miraglia, 2017).

Procedure

Throughout this research we engaged and continue to engage in our personal art-making practice, and journaling. The three authors formed a community of practice as critical friends, to discuss how art making was connected to issues of research and teaching and to help refine our practices. The three artists-teacher-researchers implemented a creative studio-based practice to explore the aforementioned research questions. Jane Dalton, used contemplative practice and stitching to explore issues of identity using mixed media processes. Kathy Marzilli Miraglia, drew from her Italian heritage to explore female images in biblical narrative, mythology and history, seeking universal problems of human culture from the female perspective. Kristi Oliver, used meditation to begin her creative process as she explored her own sense of self-identity through investigating her role as an art teacher in the world today. Data sets were on-line critiques of artwork, discussions, and journal entries. Data were analyzed for common patterns and themes.

Results: A Narrative Approach through Text and Image

Though each approach to art making reflected an individual positionality, each was rooted in the process of investigation of our own identities and the connections we made to our research and teaching contexts. Each author was in search of their authentic selves, navigating the challenges through self-study and arts-based methods.

Through analyzing journals, artwork, and critical friend dialog and critique, four major themes were identified. All three authors approached their artwork, teaching, lives, and tangled identities, through spiritual methods. 1) Regarding the creation of artwork; for Jane Dalton, it was contemplative practice and stitching, for Kathy Marzilli Miraglia, it was the pursuit of the sacred, and for Kristi Oliver, it was meditation and contemplative inquiry. Each author found that the act of creation was necessary to find their authentic selves and balance within multiple identities. 2) Regarding teaching: the challenges of communicating to students as to what is important, what is essential, what the most integral concepts are, how to uncover students’ misconceptions and positionality (regarding their own identities and their ability to connect to their students’ identities), and how to lead students to create their own unique art lessons were prime concerns. 3) Regarding research: navigating challenges, finding balance within teaching, researching, and creating artwork was complicated by daily obligations concerning home, well- being, and professional life. 4) Regarding personal lived experience: sharing personal instances helped to support each other through difficult and unexpected challenges with restorative and empathetic effects without judgment.

The following sample statements, in no particular order, were crafted here to summarize and explain the essence of our work for readers of this chapter. These statements reflect, in an abridged form, themes that were derived from the data. The accompanying art works were not meant to be self- portraits, either literally or metaphorically, but are examples of actual works of the three authors that were included in the critique process as critical friends.

Jane Dalton: Stitching as Research

For me, stitching is research. There is a rhythm of my hands working, slowly and continuously, creating focus and comfort. I believe stitching, whether by hand or free motion machine, is a way of exploring that allows for contemplation and internalizing, bridging the inner and outer worlds; it is a contemplative practice which creates presence and focus. The time devoted to making allows for a slower, almost meditative pace, softening the chatter of my mind, and reducing stress. (Dalton, Journal Entry, 2019).

I define myself as a contemplative educator, that is, one who integrates introspection and experiential learning to support pedagogy and self-understanding. Whether teaching or working in my studio, I begin with a period of mindfulness meditation paying attention to what’s going on in my body to feel centered before beginning either practice. In my experience, bringing personal practice into my classroom has strengthened pedagogy, offering a solid foundation for teaching while modeling this practice for students who aim to establish their own contemplative art practice.

I believe artistic expression gives voice to our authentic selves that is at the core of our identity construction. I view artmaking as a meditative process of inquiry where I seek to understand the ever-evolving self that is continually constructed and reconstructed through interactions with materials and experiences in the present moment. This process offers a window through which I can work at a slow, mindful pace inviting reflection: What is it that inspires me to create? What can the process tell me about myself?

Stitching as a meditative practice is a resource for connecting and reconnecting with the desire to create, which was the impetus for me becoming an art teacher. In particular, I explore the circle, using a range of materials and processes. The circle is a shape that is found repeatedly throughout the world and is an archetypal symbol of wholeness and integration that connects mind, body, and spirit. I believe the promise of wholeness is embedded within each of us and the circle is a reminder of this potential. Stitching the circle, repeatedly, with the focus more on process than product, becomes a ritual of seeking wholeness. Both making and meditation allow me to find balance in my life; both are generative, and, both demonstrate to students the value of artistic practice as an essential element in my identity construction.

Figure 1

Circle. Handmade felt, hand embroidered (Used with permission, Jane Dalton, 2019).

Figure 2

Circle. Free motion embroidery (Used with permission, Jane Dalton, 2019).

Figure 3

Circle. Free motion embroidery (Used with permission, Jane Dalton, 2019).

Kathy Marzilli Miraglia: Pilgrimage as Research

As a woman artist, educator and researcher, I am engaging in a continuous quest to understand the multiple aspects of my identity as they relate to my research, teaching and art making. During a recent sabbatical, I went on an actual pilgrimage to Messina, Italy. I traveled to sacred places in search of female heroes, goddesses, saints, and martyrs, investigating subjects with “common roots, interesting differences, and universal problems of human culture from the female perspective – and their surprising parallels with our own” (Leon, 1995, p. 3). On that pilgrimage, and through an arts-based self-study, I realized that my research and creative work focused on my relationship with my Italian heritage and spiritual beliefs. Through drawing and mapping, I found that I must come to certain understandings before moving forward or enacting change.

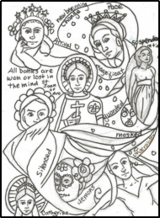

For example, the drawing depicted in Figure 4 is an entry from my visual journal. In this drawing, some figures are frightful, representing obstacles that hinder my progress. Other figures represent helpful energies and forces imagined as critical friends or spirit guides who remind me that often ‘the battle is won or lost in the mind’ (Joan of Arc). At the bottom of the drawing, I am feeling overwhelmed and underwater, silenced, and guarded. My ability to create artwork is suspended or interrupted because of administrative duties and obligations. The battle ultimately can only be won by removing the obstacles that exist in my own mind and coping with obstacles that I cannot change. Through engaging in creative work as a self-study methodology, my goal was to identify the current patterns occurring in my life, change those patterns that are not working for me, and grow by gaining clarity and self-knowledge. I aspire to embody the figure at the top left of the page, she is the visualization of reconciliation with my creative self (Klein & Miraglia, in press).

A sabbatical afforded me the time to slow a hurried pace, renew my energy and spirit, to examine problems and successes, and reconsider my multiple professional practices. Realizing the time and resources it takes to teach and make art, in addition to the pressures of conducting research, I have questioned how to best motivate students to pursue their own research and create their art that would inform their teaching practices.

Figure 4

Drawing from a journal page (Used with permission, Kathy M. Miraglia, 2019; in Klein & Miraglia, in press).

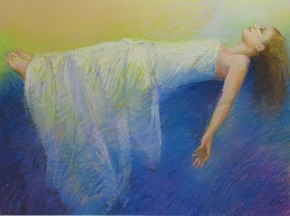

Figure 5

I Dreamed I was Floating. Pastel (Used with permission, Kathy M. Miraglia).

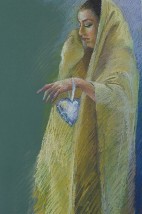

Figure 6

Lamentata. Pastel (Used with permission, Kathy M. Miraglia).

Kristi Oliver: Creative Expression as Research

When I engage in creative making, it allows me to explore my sense of self, specifically how I relate to, process, and navigate the world. I begin the process by practicing mindfulness, trying my very best to focus on what is happening and how I am feeling in that moment.

Typically, this means I start with meditation, often breathing through the process in a way that attempts to free the creative process from self-inflicted judgement and self-doubt. In this way, I am able to work through issues and events that are weighing on my mind. Through stressful times and challenging situations, this artistic practice has helped to keep me to stay grounded while providing comfort and stability through times of turmoil. During these stressful times, the only work I could create was informal, sketch-like or unplanned, which is very different from the way I typically create.

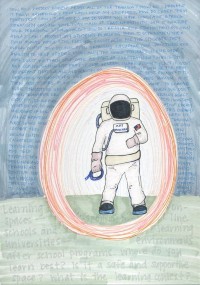

As a naturally empathetic person, I find it easy to put the needs of my students before my own. This can be exhausting, especially when navigating an already demanding schedule balancing teaching, creating, and researching. To help, I have to consciously remind myself that practicing self-care is important and that working through whatever is weighing on me through art to let go of negativity and unnecessary stress. The work displayed in Figure 7 is a page from my visual journal. In this self-portrait where I am bundled safely inside a protective suit, in attempt to repair the boundary that provides a secure layer between myself and negative energy. This work is a reminder to practice self-care for healing so that I can be a strong and effective teacher.

Figure 7

Drawing from a journal page, (Used with permission, Kristi Oliver, 2019).

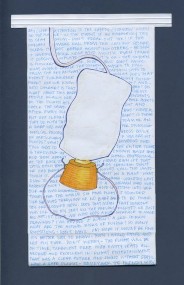

Figure 8

The Pleasures of Airline Travel, marker on bag. (Used with permission, Kristi Oliver, 2020).

Since transitioning to a new professional position, I have been traveling more often to work with art teachers from various districts across the country. The drawing (See Figure 8) explores the physicality of airline travel and the inherent stress of flying. Both creative works act as visual reminders paired with written text created in a stream-of-consciousness style aiming to act as personal notes to myself documenting my own thoughts and reflections on the experience at hand. These notes help me let go of lingering stressors and refocus my attention on the immediate demands of being an artist-teacher-researcher.

Discussion

Participating as critical friends in a community of practice held us accountable to find the time to engage in the work while keeping us focused on art making as a tool for research and generativity. Without this community, professional demands would have taken full precedence, putting artmaking to the side. As critical friends in different parts of the US, we met on Zoom and phone conferences to review and discuss each other's work, issues, and journal entries. As previously explained, we then analyzed journals, artwork, and critical friend dialog to identify themes.

We found that when the demands of teaching subsumed creative engagement with artistic practices, we may become mechanical in our teaching, less inspired, and on the cusp of feeling burned out. We see similar outcomes in our students when overwhelmed and potential burnout manifests as they juggle employment, academic assignments, and/or student teaching practicum. In their future careers as art teachers, meeting expectations in the age of accountability could potentially disengage them from the original impulse for becoming art teachers: that of making and expressing through creative and artistic practices (Dalton & Dorman, 2018).

Teaching and studio work is usually a solitary practice. Implementing a critical friends structure played a significant role in our professional development by articulating and understanding the various ways our artist-teacher-researcher identities impacted each distinct role. While using a studio-based practice helped to cultivate deep reflection and critical thinking on the content of our artwork and ourselves, the values identified through engaging in the creative process were evident as we supported each other to establish and maintain a studio practice which in turn informs the teaching of art.

As teacher-educators in art education, we have found that students desiring to be K12 art teachers were first artists who were compelled to create while understanding the transformative power of art. Ironically, our students already work in a community of practice while they remain students and are able to receive and give feedback about their work, their challenges and struggles in becoming artists and teachers. We, however, had to create a community of practice for ourselves. Therefore, this research is important as a method to mentor and prepare our students when they become in-service teachers by creating a community of practice when they graduate, and to utilize their studio practice as professional development. We must remember to model creative practice as self-care for our students which is essential to demonstrate the ways of how to balance our many roles while actively addressing the overwhelming demands of the artist-teacher-researcher.

Conclusion

Coming to these conclusions reaffirmed our decision to continue this research. “The complicated identities of art educators require multiple methods and strategies to accommodate the multiple facets of practice and the shifting identities of teachers as they evolve and assimilate new knowledge and experiences” (Klein & Miraglia, 2017, p. 29). Aesthetic forms communicate what we know and invite others to commune with our own understanding and personal transformation (Dalton & Dorman, 2018).

The tendency embedded in the positivistic legacy and in a culture of accountability to value measurement, objectivity, and generalization with greater importance above the creative and imaginative (Griffiths, 2011) still impacts the way we teach and assess. This is why it is so important that models for art educator professional development accommodate nonlinear and visual processes for understanding practice in ways that embrace and honor a diversity of lived experiences. Integrated models offer potential for developing visually reflective practitioners who can envision and re-vision and transform and reform their practices through the eyes of an artist. (Klein & Miraglia, 2017, p. 29- 30)

As artists, we become weavers of our own life. Our works of art become the tapestries that reveal the ways in which we embody who we are, and the work we do as art teachers. Furthermore, in higher education, as in K12 settings, art teachers are often isolated, working independently. As critical friends, we found our collaboration to strengthen our work and essential to staying true to the path of the artist that is generative. We found that creating our own artwork, required constructive feedback and time to ponder and reflect. We supported each through difficult issues and events that could have hindered our ability to create artwork, teach, or conduct research. We not only shared concerns but gave constructive feedback that allowed us the space and understanding to move forward without judgment. Ultimately, the three of us create using varying spiritual approaches. We found a common way to strengthen and direct our teaching, incorporating mindfulness, and contemplative practice into our teaching practice.

References

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. W. (2012). Arts based research. Sage.

Beauchamp, C., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39(2), 175-189.

Buffington, M., & McKay, S.W. (2013). Practice theory: Seeing the power of art teacher researchers. National Art Education Association.

Bullough, V., & Pinnegar, S. (2001). Guidelines for quality in autobiographical forms of self-study. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 13-21.

Costa, A. L., & Kallik, B. (1993). Through the lens of a critical friend. Educational Leadership, 51(2), 49-51.

Garoian, C. (2006) Art practice as research: Inquiry in the visual arts. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 108-112.

Griffiths, M. (2011). Research and the self. In M. Biggs & H. Karlsson (Eds.), The Routledge companion to research in the arts, (pp. 167-185). Routledge.

Daichendt, G. J. (2010). Artist-teacher: A philosophy for creating and teaching. Intellect.

Dalton, J., & Dorman, E. H. (2018) Blending the professional and personal: Cultivating authenticity in teacher education through contemplative pedagogy and practices. In Pushing boundaries and crossing borders: Self-study as a means for knowing pedagogy. Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices (SSTEP), American Educational Research Association.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. W. W. Norton and Company, Inc.

Irwin, R., Beer, R., Springgay, S., Grauer, K., Xiong, G. & Bicknel, B. (2006). The rhizomatic relations of A/r/tography. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 70-88.

Klein, S. & Miraglia, K. M. (2017). Developing visually reflective practices: An integrated model for self-study. Art Education, 70(2), 25-30.

Klein, S. & Miraglia, K. M. (in press). Developing a visually reflective practice: A model for professional self-study. Intellect.

Knowles, M. (1980). The modern practice of adult education: From pedagogy to andragogy. Prentice Hall Regents.

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In Loughran, J.J., et al (Eds.) The International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices. (pp. 817-869). Springer.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (2003), Situated learning; Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Louie, B., Drevdahl, D., Purdy, J. & Stackman, R. (2003). Advancing the scholarship of teaching through collaborative self-study, The Journal of Higher Education, 74(2), 150- 171.

McNiff, S. (1998). Art-based research. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Inc.

Miraglia, K. (2014). In the beginning: What do I need to know? In K. Miraglia and C. Smilan (Eds). Inquiry in Action: Paradigms, methodologies and perspective in art education (pp. 8-17). National Art Education Association.

Miraglia, K. M. (2017). Learning in situ: Situated cognition and culture learning in a study abroad program, in R. Shin (Ed.), Convergence of contemporary art, visual culture, and global civic engagement, (pp. 118-137). IGI Global.

Palmer, P. (1998). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. Jossey-Bass.

Pinnegar, S., & Hamilton, M. (2009). Self-study of practice as a genre of qualitative research: Theory, methodology and practice. Springer.

Schon, D. A. (1987). The reflective practitioner, 2nd ed. Jossey-Bass.

Strickland, C. (2019). The way of the artist educator: Understanding the fusion of artistic studio practice and teaching pedagogy of K-12 visual arts educators. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Lesley University.

Sullivan, G. (2005). Art practice as research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Sullivan, G. (2006). Research acts in art practice. Studies in Art Education, 48(1), 19-35. Sullivan, G. (2010). Art practice as research: Inquiry in the visual arts (2nd edition). Sage Publications, Inc.

Thornton, A. (2013). Artist researcher teacher: A study of professional identity in art and education. Intellect.

Walker, L.N. (2013). The long shadow of peer review on the preparation of artist educators. Arts Education Policy Review, 114(4), 205-12.

Wenger, E. (2008). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wilber, K. (1997). The eye of spirit. Shambhala Publications, Inc.