This chapter investigates how to support the pedagogy of choice as a means of developing learner agency. In this case study, 30 preservice student teachers participated in a hybrid pedagogical approach combining heutagogy, problem-based learning (PBL) and universal design for learning (UDL). The aim was to support learner agency by providing an environment that nurtured self-determined collaborative, authentic and ill-structured learning. The approach illustrates new opportunities in higher education teaching to bridge the gap between traditional content-focused, discipline-centred teaching and the demands of our increasingly fast paced, collaborative and technology-driven society and working environments. The study found that the students enjoyed having choice, however, experienced high levels of anxiety in exercising agency. The need for additional scaffolds to alleviate anxiety was highlighted, in particular information literacy skill building exercises, increased reflection on the learner’s experience and emotion to promote self-regulation and to nurture self-reliance and learner confidence. Further consideration needs to be given to encouraging agency during the provision of professional development for higher education educators, particularly in the context of risk taking, opening teaching approaches and articulating metacognition around their teaching decisions to students to facilitate the modelling of agency in the educational system.

Education is the process of training man(sic) to fulfil his aim by exercising all the faculties to the fullest extent as a member of society.

The implications of learner agency in today’s society

Due to the rapid pace of change (Puncreobutr, 2016), 21st century society demands new skillsets, in particular the ability to adapt, problem solve, self-appraise and collaborate between disciplines and geographical locations (Paccagnella, 2016; OECD, 2017). These skillsets are often in stark contrast to those promoted in traditional educational systems. Such systems are largely siloed, and content focused, teaching individuals’ discipline-centred skills which allow them to succeed in a specific career path (Costley & Dikerdem, 2011). Success is largely dependent on the ability of students to demonstrate prescribed learning outcomes for which they are awarded grades.

To bridge the gap between traditional education and the needs of 21st century society, students need to learn how to adapt to change by making informed choices about their own learning through agency. Educators must provide a safe space to urge students to take an active role in their learning, encouraging them to pre-empt problems, self-assess their skills level, identify their own learning outcomes, and adapt their skills (European Commission 2015; Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). In addition, educators must model agency by taking risks in their teaching, allowing themselves to be vulnerable, empathetic, and being open with their students (Hase, 2014, 2017).

If we encourage students to embrace their agency, we not only inspire them but empower them. Every environment has the potential to be a learning environment, and successful students will be the ones who have the skills to adapt (learning) environments to their individual needs. Therefore, learners’ must understand their strengths and challenges and identify strategies to support their learning. Therefore, we need to foster self-determined learners who can monitor their progress and make connections with prior learning (McClaskey, 2016).

Pedagogies that support learner agency

There are several pedagogies that support learner agency. This chapter will explore a hybrid of problem-based learning (PBL) and universal design for learning (UDL) to apply heutagogical principles, enhancing learner agency in today’s higher education system.

Problem-based learning (PBL) and learner agency

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a learner-centred pedagogy that reverses didactic education. Students explore ill-defined complex scenarios, and then identify and develop the knowledge needed to address such through a collaborative seven step process, adopting one of several team roles (Helelä & Fagerholm, 2008; O Brien et al., 2019a).

In groups, learners meet regularly to reflect, self-assess and provide feedback to their peers. Educators guide learners through the process and emphasise that PBL is not concerned with wrong or a right answers, encouraging learners to articulate their thought process for their approach (Helelä, & Fagerholm, 2008). Many of these tenets align with heutagogy particularly the focus on process, self-direction, collaboration and authentic learning (Blaschke, 2012; Hase & Kenyon, 2007).

In the initial stages, PBL learners experience a high level of anxiety (Fiddler & Knoll, 1995). Studies have also shown that there is a high drop-out rate particularly with distance and online PBL, learners cite challenges regarding identifying knowledge gaps, how to approach the PBL process, and working collaboratively. However, learners have emphasised the positive impact it has on understanding how they and others learn, thus developing self-awareness (O’Brien et al., 2019b).

The high dropout rate in the initial stages of PBL illustrate that it is far from perfect. The student experience needs to be supported to alleviate anxiety and to encourage students to embrace uncertainty to enhance their learning. In particular within PBL, we need to.

- Make learners aware of how they learn, their learning preferences and how these impact their peers, support group work and metacognition, and nurture the heutagogical principles of self-awareness and self-direction.

- Develop skills to provide opportunities for learners to appraise their own work and that of their peers, empowering students to work more effectively in groups and facilitating the heutagogical principle of collaboration and assessment.

- Creating an awareness of how learners approach PBL to alleviate uncertainty (Gibbings et al, 2015), while encouraging self-appraisal and articulating metacognitive processes to support learners to adapt their approaches (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001, p.5) and thus applying the heutatogical principle of reflection.

This chapter will explore how PBL can be integrated with UDL to nurture learner agency to empower 21st century learners.

Universal design for learning (UDL) and learner agency

Universal design for learning (UDL) is a framework that provides ALL students with equal opportunities to learn (Rose 2002). The three principles of UDL CAST (2018) provide a framework so that curricula and instruction are designed to be accessible and engaging. These principles are:

- Multiple means of engagement. Stimulates motivation and sustained enthusiasm for learning by promoting various ways of engaging with materials.

- Multiple means of representation. Presents information and content in a variety of ways to support understanding by students with different learning approaches/abilities.

- Multiple means of action/expression. Offers options for learners to demonstrate their learning in various ways, e.g., allowing choice of assessment type.

Furthermore, students are encouraged to take ownership of their learning from an early age. This supports the concept of heutagogy where the learner is at the centre of the learning process rather than the teacher or the curriculum (Hase, 2014).

Novak (2019) explores how UDL allows educators to remove barriers to learning by offering voice and choice. When we provide students with agency, we encourage them to be more engaged and creative. This, in turn, produces education that’s more equitable and inclusive.

However, when UDL is adopted, it is largely through a design framework and is not made visible to learners. UDL needs to be made explicit by leveraging it as a conversational framework to discuss learner incomes, in particular their motivations, preferences, and strengths, so they can adapt the learning environment to meet their individual needs. By using the UDL framework in this way, educators can accept learner variability as a strength to be leveraged, not a challenge to be overcome (Rose & Meyer, 2002). In addition to providing a design framework, UDL also contributes to the construct of student-centrism by emphasizing the role of UDL in the development of “expert learners” (Meyer, Rose, & Gordon, 2014).

The earlier that the principles of UDL are introduced to students, the greater are the opportunities to support the development of key skills for independent learning. This develops individuals who have the ability to curate and process knowledge and make informed choices about their learning needs and outcomes to ensure they achieve their full potential as learners.

UDL is largely dependent on the individual learner focusing on themselves and their needs. In collaborative societies, learners need to become aware of the impact that their individual preferences have on their peers and their environment. To date, UDL has not been explored as a means of applying heutagogical principles and facilitating learner agency. Combined, UDL and PBL can extend the development of learner agency to collaborative and authentic environments. We call this the pedagogy of choice which empowers and enables learners to make informed choices regarding their learning.

Pedagogy of choice

The pedagogy of choice has been referred to in various contexts. Bali (2019) defined the pedagogy of choice as a 'pedagogy or curriculum that has many opportunities for learners to make their own choices' (para. 3). Furthermore, Cummins (2009) argued that choice requires educators to challenge their assumptions regarding the current learning environment, particularly with a view to the role of the learner – students make decisions regarding what and how they learn. However, the provision of choice for learners is simply not enough; we need to support learners to develop a specific skillset to aid decision making, while applying the pedagogy of choice in practice. It is important to develop students’ skills in self-awareness, decision making and metacognition to develop their confidence in forming their own learning pathway and nurture their transition from dependent to independent learners.

Previously, we looked at two pedagogies that facilitate learner agency. PBL is process-based and collaborative, focusing on engaging learners in multidisciplinary authentic learning experiences. However, learners often feel underprepared regarding their redefined role. UDL develops the expert learner but is limited to individual preferences and choices. It does not consider pedagogical approaches such as collaborative learning, uncertainty, and authentic learning. Furthermore, UDL is largely a design framework and needs to be made explicit as a conversational framework to encourage learner self-awareness and foster agency.

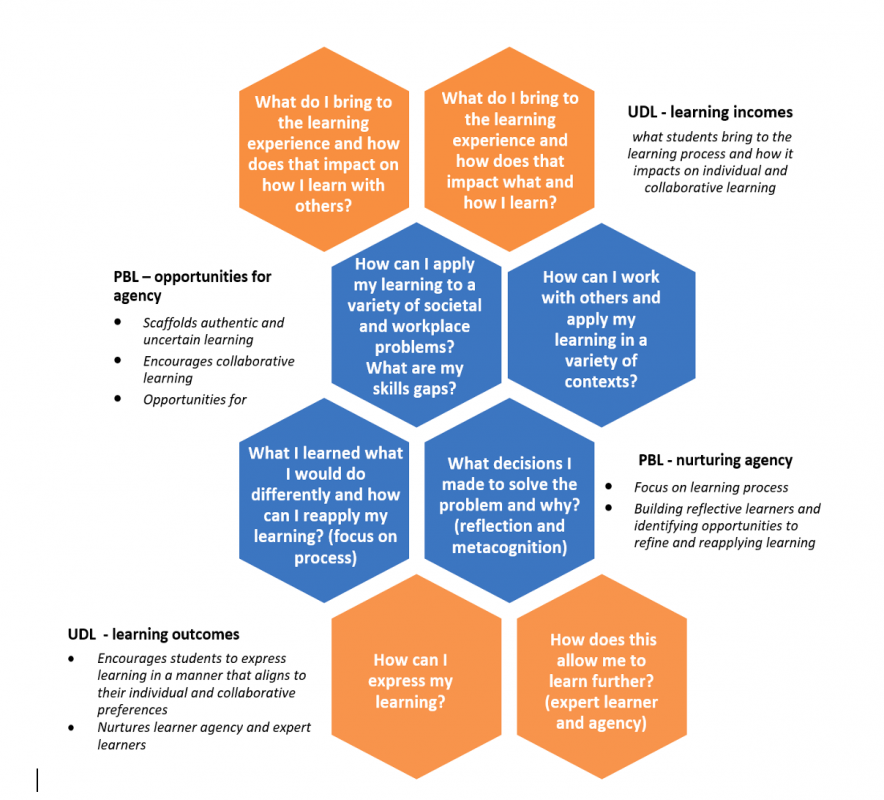

The pedagogy of choice (Figure 1) combines PBL and UDL to scaffold the students learning experience through a self-determined process of collaborative, authentic, and ill-structured learning. UDL provides opportunities for learners to consider their learning incomes through dialog (what they bring to the learning environment and what they want from it). When used transparently, UDL encourages the learner to become self-aware of his/her own preferences and how these can impact engagement with other learners and with the learning process. PBL empowers learners to make both individual and collaborative decisions, reflect on these, and explore how their learning can be applied to multiple contexts. UDL further scaffolds the experience of how learners use and express their knowledge. This holistic approach nurtures agency by providing opportunities for learners to determine their preferences, needs, and how they interact with others and the learning environment.

The next section illustrates a case study on how the pedagogy of choice has been applied in practice.

Case study on the application of the pedagogy of choice in developing learner agency

This section describes how the pedagogy of choice was applied within the constraints of the current HE system.

In September 2019, a third-year undergraduate module in educational technology was redesigned to enhance learner agency. As educational technology is constantly changing, it is difficult to teach students all technologies they could potentially encounter. Therefore, the module was adapted to empower learners to identify and critique the relevant technologies to be used in authentic contexts and how to apply these using pegogical best practice. The class consisted of 30 students who had participated in work placement the previous semester. To align with the pedagogy of choice, the module was redesigned as follows.

Identification of learning incomes. Firstly, learners participated in a poll expressing their motivation for engaging with the module and the challenges they experienced in work placement. Based on the results, the class discussed how digital learning technologies might address some of the challenges they faced. This made the module more appealing to the individual learners’ preferences, which aligns with the heutagogical principles of self-direction and reflection.

Providing opportunities for agency by incorporating authentic inquiry-based learning. The lecturer then developed a trigger which represented an authentic problem in the workplace. The learners were asked to develop a plan and a digital resource to address the problem. Learners could choose a topic they wanted to focus on. All students choosing the same topic formed a PBL group, which aligns with the heutagogical principles of collaboration and exploration.

Nurturing agency by emphasising the importance of process. In PBL, the focus is on the process and not the outcome. Therefore, learning outcomes were rewritten to value learning processes rather than learning products. For example, rather than using a particular type of technology, learners evaluated how a digital resource can be effectively used to meet the needs of a group of learners. This aligns with the heutagogical principle of capability (Blaschke, 2012; Hase & Kenyon, 2009).

Figure 1

The pedagogy of choice: A hybrid of PBL and UDL.

Providing opportunities and nurturing agency in everyday teaching. Each week learners participated in:

- A lecture discussing PBL, UDL, assessment and feedback literacy and peer feedback.

- A PBL tutorial. Students met each week in their PBL groups to develop a plan and a digital resource for the PBL trigger. Students completed one of the seven PBL steps each week. Each group was provided with an online collaborative space to complete each step of the PBL process. This encouraged students to continue their collaboration outside of class or for those who struggled with face to face expression, to contribute through alternate channels.

- A lab. Each week, a lab was provided on a different type of digital learning technology. Learners were given a poll each week and voted on the technology they would like to explore in the proceeding lab. Lab sheets and videos were provided, and the students worked at their own pace, collaborating with each other and asking the lecturer questions as needed.

In the PBL classes, we discussed the PBL process, how we might approach the trigger, and how students could evidence their learning. Lectures were largely discussion based. To illustrate the importance of process rather than product, the class evaluated different types of educational resources and discussed how everyday technologies could be used in different ways to enhance learning.

The UDL classes were discussion based and were concerned with creating self-awareness. In the context of UDL principles, we discussed: How would you like to learn in the context of UDL principles, how you would like to demonstrate your learning, what ways would you like to express this, and how would you like to engage with your peers in class and the lecturer? The last topic to be discussed in class was how the students’ learning preferences could impact the PBL group and how they collaborate, express and engage with each other. This allowed UDL to be made explicit and extended it beyond the individual. It encouraged self-awareness of how students learn individually and collaborate in groups. This encouraged learners to be empathetic towards their peers when working in groups and allow them to adapt the learning environment to their own individual and peer learning needs.

Assessment literacy classes encouraged self-appraisal, learners graded written sample assessments, and discussions were held regarding how they might express their learning in different forms, e.g., as a video, diagram, and/or podcast. The class discussed what good design plans and digital resources might look like.

In the peer assessment classes, learners developed a peer evaluation sheet in their PBL groups to encourage them to critique digital resources. Sample scenarios of peer feedback were given to groups, and discussions were held about what peer feedback might be useful and what might not. This developed self-appraisal skills.

Finally, learners engaged in peer learning as part of the assessment process. Each group presented their digital resource and were allocated a group to review. Marks were awarded to the peer reviewers regarding their ability to critique the design and pedagogical use of a digital resource.

Learning outcomes: Modelling UDL in practice

In addition, the module was delivered in line with UDL principles, and this was made explicit throughout. The lecturer explained the rationale for why they were delivering the module in the specific manner and how it aligned to UDL principles.

- Multiple forms of representation. Each week lab material was available in text, video, and podcast form. Learners could choose to physically attend class or view pre-recorded material online.

- Multiple forms of engagement. In class lectures, learners could contribute via a poll. Learners could choose to meet face-to-face or work on the problem using technology mediated spaces provided by the lecturer. PBL groups could collaborate with each other at each stage of the PBL processes using text, video, or audio.

- Multiple forms of expression. Learners could choose their mode of assessment, and they could choose to submit their assignment through text, audio (podcast), or graphically (info graphic or poster).

Challenges

Content provided in lectures was largely focused on building learner confidence and self-awareness. Therefore, learners had to identify and gather the learning material required to solve the problem trigger, and they experienced a number of challenges in transitioning to such a learner-centred approach. In particular, students found it difficult to exercise their agency when making choices regarding what to learn, how to learn, and how to express their learning in relation to the module. They relied largely on the lecturer to help them to make what they perceived as a ‘right’ decision. Also, despite scaffolding of the PBL process in lectures and through tutorials, learners struggled with how to approach the problem trigger, specifically in choosing what elements of the trigger to focus on and how to decide on the best approach to meet the needs of the problem trigger. We adopted a questioning approach to encourage students to articulate their metacognitive processes. For future iterations, providing examples of solved PBL triggers and prompts for metacognition could potentially provide additional support through the PBL process. Also, providing classes in information literacy to encourage learners to identify their knowledge gaps and guidance on how to fill these may have helped build learner confidence in exercising agency. To exercise their agency further, students could potentially develop their own problem trigger.

In addition, learners were encouraged to choose their mode of assessment and found it challenging to identify how to express their learning in different ways. Assessment literacy classes focused on exploring written modes of assessment and discussing how they might be conveyed in different ways. Further scaffolding, by providing examples of assessments in alternative modes and asking the students to provide feedback on these, may assist with addressing some of the challenges. Both assessments were weighted equally. The high stakes associated with these assignments may have inhibited learners to take perceived risks regarding their mode of assessment. Introducing shorter formative assessment, which are lower risk, to encourage learners to experiment with a variety of modes could build confidence.

Lastly, learners struggled regarding peer reviewing and feedback which lacked depth and was mainly positive. Providing opportunities for learners to generate feedback on their own digital resources or digital resources that were developed by individuals beyond the classroom may build critical thinking skills in a safe environment. Furthermore, discussing how an individual might interpret and apply this emotionally and logistically could facilitate self-appraisal and self-regulation.

Conclusion

This chapter explored a case study in which a hybrid of PBL and UDL were applied in higher education to facilitate learner agency through the application of heutagogical principles. UDL was used to nurture self-awareness in the student group, encouraging learners to consider their learning incomes from the perspective of their individual and collective needs. This prepared learners for engaging in a PBL, through a collaborative, ill-defined learning environment which they will experience in the world of work. PBL provided opportunities for students to exercise their agency and nurtured this through process-based (rather than content-based) learning, self-reflection, and metacognition, thus further developing their skills. This provided learning outcomes which valued learner agency and diversity rather than ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers.

Overall, the students enjoyed having choice, however, experienced high levels of anxiety in exercising agency. Additional scaffolds need to be provided to alleviate learner anxiety, in particular the use of examples, the integration of information literacy skill building exercises, and increased reflection on the learner’s experience and emotion throughout the process so they can self-regulate and adapt to build reliance and learner confidence. Further consideration also needs to be given in encouraging agency during the provision of professional development for higher education educators, particularly in the context of risk-taking, opening teaching approaches, and articulating metacognition around their teaching decisions to students in order to facilitate the modelling of agency in the educational system.

References

Abraham, R. R., & Komattil, R. (2017). Heutagogic approach to developing capable learners. Medical Teacher, 39(3), 295-299.

Bali, M., (2019). Pedagogy of choice for critical thinking. https://edtechbooks.org/-qrd [accessed on 6th April 2020)

Blaschke, L. M. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(1), 56-71.

Bracken, S., & Novak, K. (Eds.). (2019). Transforming higher education through Universal Design for Learning: An international perspective. Routledge London.

Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and teaching, 21(6), 624-640.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines, version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org 23/08/2020

Costley, C., & Dikerdem, M. A. (2011). Work based learning pedagogies and academic development. Project Report. Middlesex University, London, UK. https://edtechbooks.org/-JLTI [accessed on 19th August 2020]

Cummins, J. (2009). Pedagogies of choice: Challenging coercive relations of power in classrooms and communities. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 12(3), 261-271.

Downing, K., Kwong, T., Chan, S. W., Lam, T. F., & Downing, W. K. (2009). Problem-based learning and the development of metacognition. Higher Education, 57(5), 609-621.

European Commission. (2015). Education and Training 2020. Working Group Mandates 2016–2018. Brussels: European Commission.

Fiddler, M. B., & Knoll, J. W. (1995). Problem-based learning in an adult liberal learning context: Learner adaptations and feedback. Continuing Higher Education Review, 59, 13-24.

Gibbings, P., Lidstone, J., & Bruce, C. (2015). Students' experience of problem-based learning in virtual space. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 74-88.

Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2007). Heutagogy: A child of complexity theory. Complicity: An international journal of complexity and education, 4(1).

Hase, S. (2014). Skills for the learner and learning leader in the 21st century. In L.M. Blaschke, C. Kenyon, & S. Hase (Eds.), Experiences in self-determined learning, (pp. 98-107). United States: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. https://edtechbooks.org/-Kzdo

Hase, S. (2017). Four characteristics of learning leaders. TeachThought. https://www.teachthought.com/pedagogy/4-characteristics-learning-leaders/

Helelä, M., & Fagerholm, H. (2008). Tracing the roles of the PBL tutor: A journey of learning. ISBN 978-952-5685-32-9 https://edtechbooks.org/-Fxp

O'Brien, E., McCarthy, J., Hamburg, I., & Delaney, Y. (2019a). Problem-based learning in the Irish SME workplace. Journal of Workplace Learning.

O'Brien, E., Hamburg, I., & Southern, M. (2019). Using technology‐oriented, problem‐based learning to support global workplace learning. In Kenon, V. H., & Palsole, S. V. (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of global workplace learning. United States: John Wiley & Sons.

OECD, (2017). Future of work and skills: Paper presented at the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group, 15-17 February 2017 Hamburg, Germany. OECD.

McClaskey, K. (2016). Developing the expert learner through the stages of personalized learning. https://udl-irn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/McClaskey_K2016PersonalizedLearning.pdf

Meyer, A., Rose, D.H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing.

Novak, K. (2019). Models of voice and choice: Recognize teachers’ diverse experiences when implementing Universal Design for Learning strategies. Principal, 99(1), 20–23. https://edtechbooks.org/-kCNK

Puncreobutr, V. (2016). Education 4.0: New challenge of learning. St. Theresa Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2(2).

Paccagnella, M. (2016) Age, ageing and skills: Results from the Survey of Adult Skills. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 132. Paris: OECD Publishing

Savickas, M.L. & Porfeli, E.J. (2012) Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 80, 661-673

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2nd ed.). New York, NY, & London, UK: Routledge.