Wellbeing from a Growth Mindset

Wellbeing must be approached with a growth mindset (Dweck, 2008). In applying this research to wellbeing, we must recognize that a student’s or educator’s wellbeing is not a fixed aspect of the individual’s personality. By emphasizing that anyone’s wellbeing can improve with effort and with a focus on the process, individuals will see a greater increase in wellbeing than they could achieve with a product-focused fixed mindset.

Similarly, a wellbeing measurement score should not be used to categorize a school or an individual, but should be seen as a starting place for further exploration and progression. Michael Fullan (2011), the Global Leadership Director of New Pedagogies for Deep Learning, advised,

Do testing, but do less of it and, above all, position assessment primarily as a strategy for improvement, not as a measure of external accountability. Wrap this around with transparency of practice and results and you will get more accountability all round. (p. 9)

Utilizing wellbeing measurement scores to inform progress can help school leaders and individuals select wellbeing strengths on which to capitalize. Educators who use wellbeing scores to rank schools do so at the risk of their educators’ and students’ psychological safety, as many may become more likely to inaccurately report their wellbeing. Furthermore, there is a correlation between low socioeconomic status and low levels of wellbeing (see section on Wellbeing and Socioeconomic Considerations). Consequently, ranking schools by their wellbeing scores would not only be counterproductive and harmful to the psychological safety of the school, but would disadvantage the already disadvantaged. Instead, position the data you collect to leverage individual and organizational growth and capacity.

Section Summary

- Our beliefs about ability shape our efforts. Growth mindsets strengthen confidence in the ability to improve characteristics; to decrease depression, anxiety, and aggression; and to improve academic performance.

- Educators should view wellbeing from a growth mindset: (a) use scores to help schools improve and capitalize on their strengths, and (b) do not categorize schools based on wellbeing scores.

Suggestions for Further Research

Dweck, C. S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Ballantine Books.

Fullan, M. (2011). Choosing the wrong drivers for whole system reform. Centre for Strategic Education, 1-22.

Miu, A. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2015). Preventing symptoms of depression by teaching adolescents that people can change: Effects of a brief incremental theory of personality intervention at 9-month follow-up. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(5), 726–743. https://edtechbooks.org/-SjMf

Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33-52. https://edtechbooks.org/-PGj

Yeager, D. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). An implicit theories of personality intervention reduces adolescent aggression in response to victimization and exclusion. Child development, 84(3), 970-88

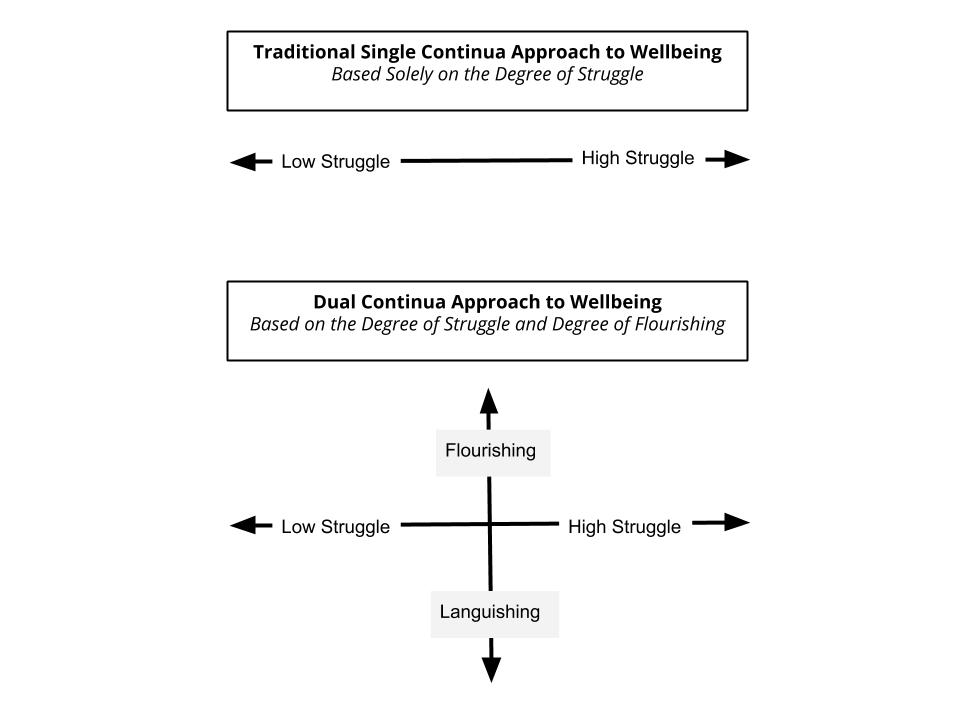

Wellbeing Viewed on Dual Continua

Many traditional approaches to wellbeing view an individual’s wellbeing on a single continuum based on their degree of mental or emotional struggle, defining wellbeing as solely contingent on the challenges faced. However, current research in the field of positive psychology supports wellbeing as measured on two continua: the degree to which an individual is struggling and the degree to which they are flourishing. Using both continua, struggling and flourishing, provides a more accurate depiction of an individual's experience. This approach supports the reality that many individuals experience wellbeing (flourish) despite challenges (e.g., mental illness) and takes into account the self-efficacy of those who live happily despite challenges. The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences between the traditional single continuum and dual continua models.

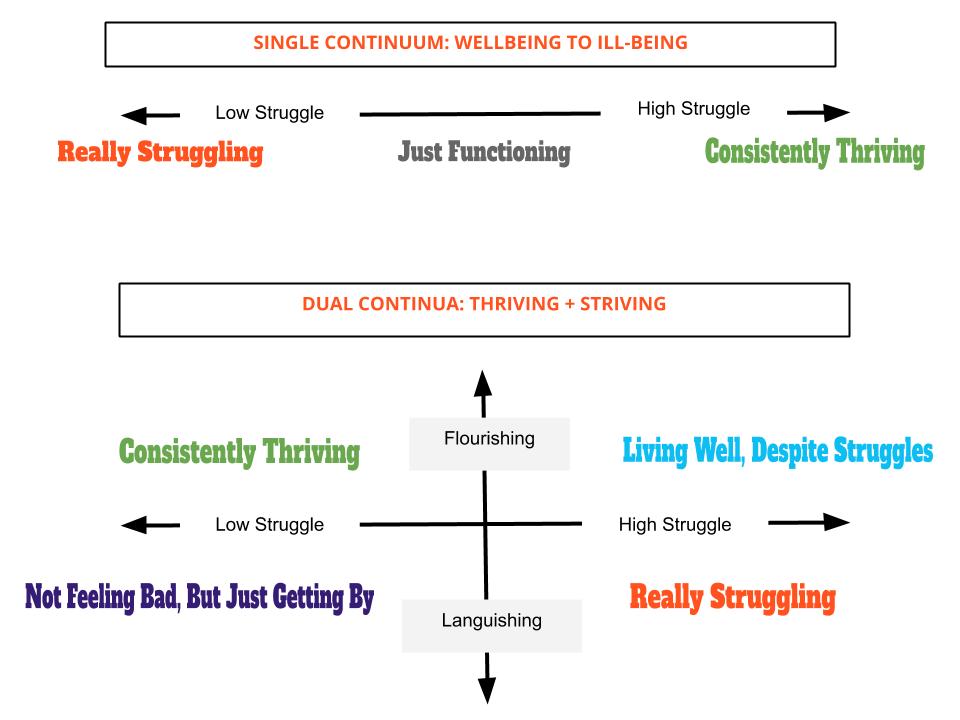

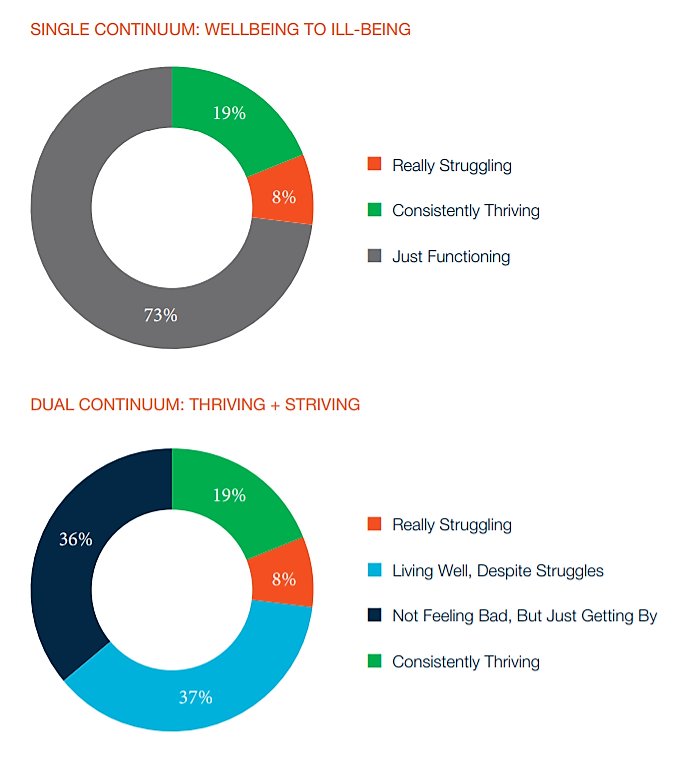

One study at TheWellbeingLab surveyed over 2,000 employees using a similar dual continua model (see graphic to the right). On the single continuum model, only three groups emerged: ”really struggling,” “just functioning,” and “consistently thriving.” On the dual continua model, researchers found that two separate groups emerged from the “just functioning” cohort, which represented 73% of all employees (TheWellbeingLab & Australian HR Institute, 2018). These two groups, represented by the descriptors “living well despite struggles” (light blue) and “not feeling bad, but just getting by” (dark blue), represented the experience of 37% and 36% of employees respectively (see chart below).

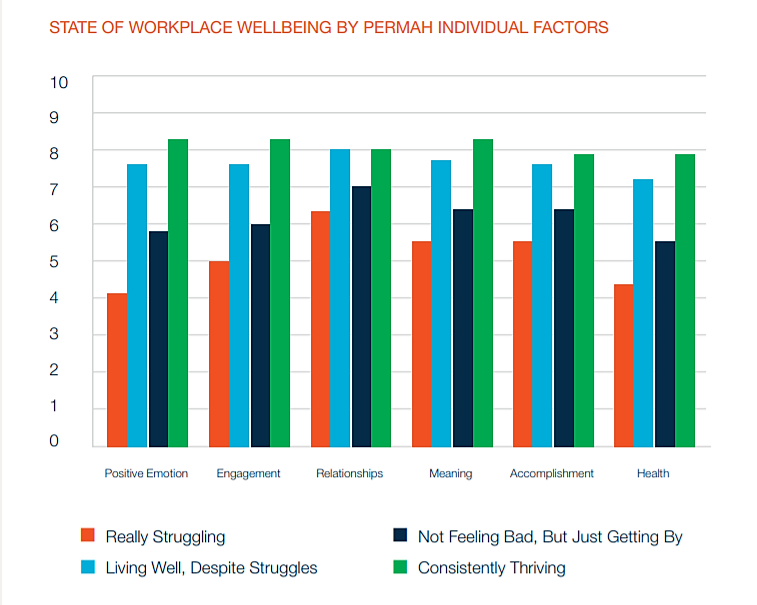

Acknowledging the two distinct groups that emerged from those normally classified as “ just functioning” is crucial to support and foster individual wellbeing. Those who are “living well despite struggles” share more characteristics with thriving individuals. They enjoy more positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, achievement, and health than those who are “not feeling bad, but just getting by.” The graphic below illustrates how the levels of each PERMAH factor for those who are “living well despite struggles” (the light blue bar) are closer to those who are “consistently thriving” (green bar) than to those who are “not feeling bad, but just getting by” (dark blue bar).

As this study shows, individuals demonstrating resilience and experiencing wellbeing despite struggles (“living well despite struggles”) do not need the same types of support as those succumbing to challenges. These resilient teachers and students do not need to be convinced of the importance and power of wellbeing as they already prioritize and experience wellbeing in their lives. Consequently, they may simply need support to recognize new resources and practice with the tools they already use to increase their wellbeing. Comparatively, those whose struggles negatively impact their wellbeing (“not feeling bad but just getting by”) can greatly benefit from learning about the importance of prioritizing wellbeing and gaining new tools to take control of and increase their wellbeing.

By conveying to students and employees that thriving is possible despite struggles, you help create the psychological safety needed to talk about challenges and reduce the negatively associated stigmas. Conversely, without recognizing it is possible to simultaneously struggle and thrive, employees and students may feel pressure to inaccurately report their wellbeing and cover up challenges they experience (McQuaid, n.d.). Viewing wellbeing on dual continua can help you better tailor support to individuals and cultivate a school culture where internal states of wellbeing need not be controlled by external struggles.

Section Summary

- Wellbeing exists on dual continua of flourishing and struggling.

- Viewing Wellbeing on dual continua can help you better tailor interventions and resources to the individual needs of teachers and students. For example, some flourish despite high levels of struggle (“living Well, despite struggles”) and experience wellbeing similar to those who are flourishing. These individuals do not need the same type of support as those who are languishing and experiencing high levels of struggle.

- Emphasizing that it is possible to thrive despite struggles helps foster psychological safety in schools and create an internal, rather than external, locus of control over personal wellbeing.

Suggestions for Further Research

Keyes, C. L. (2013). Mental health as a complete state: How the salutogenic perspective completes the picture. Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health, 179-192. https://edtechbooks.org/-PGj

McQuaid, M. (n.d.). Are our wellbeing measures doing more harm than good? Podcast and cheatsheet with Dr. Peggy Kern. https://edtechbooks.org/-RrW

TheWellbeingLab & Australian HR Institute. (2018). The Wellbeing Lab 2018 Workplace Survey: The State of Wellbeing in Australian Workplaces (Publication).

The visuals included in this section are included with permission from The WellbeingLab 2018 Workplace Survey: The State of Wellbeing in Australian Workplaces by Michelle McQuaid. Refer to https://www.michellemcquaid.com/ for more resources relating to this and other wellbeing topics.

Wellbeing Impacted by the System

Individual wellbeing must be considered as existing within a system. Systems-informed positive psychology (SIPP) merges positive psychology with the holistic nature of systems science. SIPP acknowledges that systems influence the individual. Siokou (2016), a pioneer of this line of thought, explained, “Rather than seeing contextual factors as noise, [SIPP] embraces these factors and helps us understand all the different pieces that affect the individual in their daily life” (n.p.). Thus amid our individual efforts to improve our own and others’ wellbeing, our progress can be hindered or propelled forward by the organizations to which we belong. Kern, a colleague of Siokou, also a pioneer leader in SIPP, illustrated this point:

At the individual level there’s a range of positive psychology interventions that you can do to improve your own wellbeing. But if you’re working in a very dysfunctional place, even the best people are going to struggle over time, and so you need structures that will support you to really flourish. (Kern & McQuaid, n.d., n.p.)

Considering the impact of the system on wellbeing, we have included several measures and tools designed to assess and improve your school’s organizational culture.

SIPP recognizes that systems are dynamic and responsive to change, and that even though individuals are responsible for the parts of the system they influence, their environment is often out of their control (Kern, 2017). When working to improve the wellbeing of your students and educators, you must consider the systems they work within daily and recognize how these systems impact their wellbeing. Additionally, SIPP recognizes that wellbeing looks different as experienced by different people. Consequently, schools should focus on helping students and staff develop the skills to maintain their own personal balance of wellbeing (rather than attempting unsustainable constant improvement).

Furthermore, we must recognize that much of wellbeing comes from our interactions with others and can be significantly improved by a positive system. Focusing too much on our personal wellbeing may do more harm than good. Kern observed, “One of the biggest findings in the wellbeing research is that other people matter, and yet today most of the positive psychology interventions being studied are very individually focused rather than [responsive to] the ways in which our experiences are socially constructed” (Kern & McQuaid, date, page). Researchers Kern and McQuaid recommended creating a systems map to help you visualize how your initiative will impact the system, better understand and identify the pressures and values, know where to focus your attention, and analyze in which direction to move forward (Kern & McQuaid). An example of a systems map is included in the “Suggestions for Further Research” section below. As you will notice, systems maps can vary in focus, purpose, and organization. For example, Baker (2016) has recommended mapping relational energy by recording how each person in your system affects your energy from “very energizing” to “neutral” to “very deenergizing.”

However a map is organized, the goal is the same: to highlight the various factors interacting in a system and how they influence each other. If individual interventions or measures aren’t providing the improvements you hoped for, consider improving the interactive systems.

Section Summary

- Wellbeing exists within systems that either hinder or enhance your efforts to increase individual wellbeing.

- Wellbeing does not look the same to everyone.

- Your wellbeing goal should not expect constant improvement but emphasize reliable balance and self-efficacy.

- Consider utilizing a systems map.

Suggestions for Further Research

Baker, W. (2016, September 30). The more you energize your coworkers, the better everyone performs. https://edtechbooks.org/-dDxz

Leverage Networks. (n.d.). The systems thinker. https://thesystemsthinker.com/

Kern, P. (2017, March 9). Tenets of positive systems science. Systems Informed Positive Psychology Blog. www.peggykern.org/systems-informed-positive-psychology-blog

Kern, P., & McQuaid, M. (n.d.). Peggy Kern on is positive psychology too focused on the individual? (Podcast). www.michellemcquaid.com/podcast/mppw43-peggy-kern/.

Murphy, J., & Louis, K. S. (2018). Positive school leadership: Building capacity and strengthening relationships. Teachers College Press.

Siokou, C. (2016, August 29). Introducing positive systems science. Systems Informed Positive Psychology Blog. www.peggykern.org/systems-informed-positive-psychology-blog.

For examples of systems maps, use the following link to the Foresight Mental Capital and Wellbeing Project (2008). Systems maps. The Government Office for Science, London. https://edtechbooks.org/-Ypf

Wellbeing and Socioeconomic Considerations

Systems can either foster or impede efforts to increase individual wellbeing. For example, low socioeconomic status places individuals in a system correlated to lower levels of psychological health and greater likelihood of mental illness in children (Ge, 2017). The connection between low SES and decreased wellbeing has also been observed in adults (Kaplan, Shema, & Leite, 2008). The interaction between SES and wellbeing highlights the importance of viewing wellbeing on dual continua and as part of a system. Children from low SES backgrounds (systems) face more struggles than their middle class peers. However, by viewing wellbeing on dual continua, educators can help these children realize they have the same potential to thrive as their peers, even as their struggles increase in number or size.

Delving into the relationship between SES and wellbeing, researchers have found that the SES impact on wellbeing may be determined by a single condition: parent involvement. Researchers in China discovered “socioeconomic status does not have a significant effect on well-being when social support is taken into consideration” (Chu, Li, Li, & Han, 2015, p.159). Another study found that with mediation of parent involvement within positive parent and child relationships, socioeconomic status was not significantly related to child wellbeing (Ge, 2017). However, a similar study qualified the generalization:

[Although] parental involvement does act as a valuable source of familial social capital and also operates to reduce the harmful effect of childhood poverty . . . parental involvement was not sufficient to completely cancel the negative association between poverty and education; instead it acted as a “partial” mediator. (Hango, 2005, p.14)

As these studies show, the effects of poverty on child wellbeing can be reduced through parent involvement. Living in a low socioeconomic system does not impact children as much as absence of an active parent in their life. While the research is rather recent, involving parents in the conversation of wellbeing can be helpful in empowering children from low SES backgrounds. Consider how the parents of your students can take part in your school’s program of wellbeing.

Section Summary

- Low socioeconomic status is correlated with lower levels of wellbeing, but viewing wellbeing as dual continua means these children can still flourish despite opposition.

- Parent Involvement has the greatest impact on child wellbeing, mediating some of the negative effects of low socioeconomic status. Consider involving parents in your school’s wellbeing efforts.

Suggestions for Further Research

Chu, X., Li, Y., Li, Z., & Han, J. (2015). Effects of socioeconomic status and social support on well-being. Applied Economics and Finance, 2(3). https://edtechbooks.org/-PGj

Ge, T. (2017). Effect of socioeconomic status on children’s psychological well-being in China: The mediating role of family social capital. Journal of Health Psychology. https://edtechbooks.org/-ntj

Hango, D. (2005). Parental investment in childhood and educational qualifications: Can greater parental involvement mediate the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage? Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion (98) 1371-1390. https://edtechbooks.org/-PGj

Kaplan, G. A., Shema, S. J., & Leite, C. M. (2008). Socioeconomic determinants of psychological well-being: The role of income, income change, and income sources during the course of 29 years. Annals of epidemiology, 18(7), 531-537.