Standard 5.3: Constitutional Issues Related to the Civil War, Federal Power, and Individual Civil Rights

Analyze the Constitutional issues that caused the Civil War and led to the eventual expansion of the power of the federal government and individual civil rights. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T5.3]

Storming Fort Wagner, Public Domain

Storming Fort Wagner, Public Domain FOCUS QUESTION: What is the Legacy of the Slavery and the Civil War Today?

Five generations have passed and the “Civil War is still with us,” declared historian James M. McPherson in 1988 (p. viii), and it remains with us today.

The Civil War happened in a country where the Constitution promised to “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity,” but these freedoms were available to only some of the population.

The Civil War happened in the world’s largest slaveholding country at the time when 3.9 million of the nation’s 4.4 million black people were enslaved (Gates, 2014).

"The hard truth," wrote historian Andrew Delbanco (2018, pp.1, 2), "is that the United States was founded in an act of accommodation between two fundamentally different societies" - an industrializing North where slavery was fading or gone and an agricultural South where slavery was central to its and the nation's economy. Slavery, and the flights for freedom of fugitive slaves, "exposed the idea of the 'united' states as a lie."

Slavery was the fundamental cause of the Civil War. Northern Abolitionists sought to abolish slavery as an inhumane system at odds with the ideals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Other people in the North did not want new territories joining the union as slave states. People in the South sought to preserve slavery, both as an economic system and a way of life based on white supremacy and human bondage.

The Civil War cost the lives of more Americans than all the nation’s other wars combined and was followed by more than a century and a half of ongoing struggles by Black Americans to achieve civil rights and constitutional freedoms in American society.

Today, the United States still struggles to secure freedom, liberty, and justice for all. The modules for this standard are designed to explore key events and constitutional issues that led to the coming of the Civil War to help understand why that war was fought and its unfinished legacy in American society today.

1. INVESTIGATE: The Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott Case, the 54th Volunteer Regiment during the Civil War, and Juneteenth National Independence Day

Any list of key policies and events leading to the Civil War generally include the following taken from the 2018 Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework:

- The Missouri Compromise (1831-1832)

- South Carolina Nullification Crisis (1832-1833)

- Wilmot Proviso (1846)

- The Mexican-American War (1846-1848)

- Compromise of 1850

- Publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851-1852)

- Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854)

- The Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857)

- Lincoln-Douglas debates (1858)

- John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859)

- Election of Abraham Lincoln (1860)

Teaching and learning materials for these topics are online at the resourcesforhistoryteachers Events Leading to the Civil War wiki page.

The following topics focus directly on constitutional issues related to governmental power and individual civil rights.

The Missouri Compromise

In 1819-1820, Missouri’s request to enter the union as a new state created a crisis which foreshadowed the nation’s emerging disputes over slavery. Many in the North opposed the admission of another slave state, particularly since it would upset the then equal balance of free states (NH, VT, MA, RI, CT, NY, NJ, PA, OH, IN, IL) and slave states (DE, MD, VA, KY, TN, NC, SC, GA, AL, MS, LA, AR).

A group of senators, Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, authored the Missouri Compromise. The compromise balanced Missouri's admission to the Union as a slave state with the admission of much of Massachusetts' northern territory as a free state—what is now the state of Maine.

The southern border of Missouri (the parallel 36°30′ north, 36.5 degrees north latitude) became a demarcation line for the status of slavery in new states—states admitted to the south would be slave states while states to the north would be free states. No new territory north of the line (except the proposed borders of Missouri itself) would permit slavery.

Portrait of Henry Clay (1818), Public Domain

Portrait of Henry Clay (1818), Public DomainKnown as the “Great Compromiser,” Henry Clay served in Congress for nearly 40 years, in both the House and the Senate, and was Secretary of State under President John Quincy Adams. He was a contender for the Presidency five times, running three times in 1824, 1832, and 1844. Learn more about Henry Clay by viewing a restoration of a famous painting entitled Henry Clay in the United States Senate.

Dred Scott v Sanford Supreme Court Case

In 1847, having lived in the free state of Illinois and the free territory of Wisconsin, Dred Scott, a Black man, sued in court for the freedom of his wife and daughters who still resided in Missouri, a slave state. The case went to the Supreme Court where in 1857 Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, a supporter of slavery, wrote in the majority opinion that Negroes “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever profit could be made by it” (quoted in The Dred Scott Decision, Digital History, 2019, para. 7).

Posthumous Portrait of Dred Scott, 1857, Public Domain

Posthumous Portrait of Dred Scott, 1857, Public DomainIn summary Taney opined, the phrase “all men are created equal” clearly did not, and could not, apply to the people held in slavery. They could not become citizens. The Court further said the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional on the grounds that the federal government had no power to regulate slavery.

Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis who began his law career in Northfield, Massachusetts, wrote a famous dissent in the Dred Scott Case, stating it was "not true, in point of fact, that the Constitution was made exclusively by the white race." Blacks were "in every sense part of the people of the United States [as] they were among those for whom and whose posterity the Constitution was ordained and established" (quoted in “Franklin County's U.S. Supreme Court Justice," The Recorder, May 3, 2013, p. 6). There is more on Curtis' decision at the website Famous Dissents.

Portrait of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Public Domain

Portrait of Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Public DomainCurtis later served as Chief Defense Counsel during the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson.

The 54th Volunteer Regiment During the Civil War

In 1863, some 80 years after abolishing slavery, Massachusetts was the first state to recruit black soldiers to fight for the Union in the Civil War with the formation of the Massachusetts Volunteer 54th Regiment.

The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, Boston, MA, by Daderot, Public Domain

The Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial, Boston, MA, by Daderot, Public DomainThe story of Black soldiers is an important milestone in the struggle for civil rights.

Nearly 180,000 free black men and escaped slaves served in the Union Army during the Civil War. But at first they were denied the right to fight by a prejudiced public and a reluctant government. Even after they eventually entered the Union ranks, black soldiers continued to struggle for equal treatment. Placed in racially segregated infantry, artillery, and cavalry regiments, these troops were almost always led by white officers. (Constitutional Rights Foundation, 2020, para. 1)

Black troops fought in 449 battles, one-third of all black soldiers died, and a dozen were awarded Congressional Medals of Honor. In addition to heroism in battle (the 54th Massachusetts suffered 40% casualties in the Battle of Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor), this unit refused pay as a protest against federal government policies that paid White soldiers more than Black soldiers.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Analyze Stories Across State Lines

- Events:

- The Missouri Compromise

- The Mexican-American War

- The Compromise of 1850

- Kansas-Nebraska Act

- The Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford

- John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry

- The election of Abraham Lincoln

- Choose a pre Civil War event or piece of legislation from the list below. Find two original news publications about the event, one published in Northern territory and one published in Southern territory. Highlight and annotate the differences in the reporting of the event.

- Curate a Collection

- Create a multimodal collection of the history of black soldiers in American wars (using Wakelet, Google Slides/Docs, Microsoft Word/PowerPoint, or Adobe Spark Page).

- Analyze Recruiting Advertisements

- Review the advertisements intended to recruit soldiers for the Civil War. Compare and contrast the language used to recruit White soldiers and Black soldiers.

Online Resources for The Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott Case, and the 54th Volunteer Regiment During the Civil War

Special Topic Box: Juneteenth: A Holiday Celebrating Freedom

Juneteenth is an annual holiday that happens on June 19. Also known as Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Liberation Day, and African American Emancipation Day, it is the “oldest known celebration commemorating the end of the slavery in the United States” (National Archives, June 19, 2020, para. 2). It was recognized in 47 states and the District of Columbia before it became a national federal holiday with the passage of the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act on June 17, 2021.

You can view President Biden signing the bill into law here.

Juneteenth Flag | Public Domain

Juneteenth Flag | Public DomainJune 19th was the day in 1865 when Black people in Galveston, Texas learned from Union General Gordon Granger’s General Order Number 3 that slavery had ended, ironically as historian Annette Gordon-Reed (2021) noted “two years after the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed, and just two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses G. Grant at Appomattox” (p. 11). General Order Number 3 did not abolish slavery throughout the nation nor had the Emancipation Proclamation. It took the addition of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to do that and the 13th Amendment did not end the segregation and oppression of Black Americans; discriminations that continue today.

For more about the day, you can go to the Juneteenth website from the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. The date was first celebrated in the Texas capitol in 1867 under the direction of the Freedman's Bureau and became part of the public calendar of events in 1872.

Juneteenth matters because it is essential to honor occasions when people achieved freedom from oppression and slavery - in this country and around the world. By celebrating Juneteenth, in the words of Henry Louis Gates Jr., Black Americans, and Whites too, create a “usable” past that honors the contributions of those who came before while reaffirming the present-day work and struggle to achieve more fair and just futures for all (What is Juneteenth? from 100 Amazing Facts about the Negro, para. 17).

Celebrating holidays for freedom is important in other ways as well, for as historian James W. Loewen has noted in his book Lies Across America (2019), the use of markers, monuments, and preserved historic sites to commemorate the past has been dominated by racism toward people of color. In state after state, Loewen argues, historic sites make heroes out of people who opposed civil rights while neglecting those who fought to make real the promises of freedom and justice for all.

What other days deserve to be known as holidays for freedom? Henry Gates Jr. cites April 16, 1862 (the day slavery was abolished in the nation’s capitol), January 1, 1863 (the day the Emancipation Proclamation took effect), and May 28, 1865 (the first Memorial Day when African Americans honored dead Union soldiers in Charleston, South Carolina) as notable occasions. What other days and dates would you add to the list for Black Americans? What days and dates could be set forth for Native Americans, Latinx Americans, women, and other marginalized and oppressed groups in U.S. history and society?

Suggested Learning Activity:

- As a class, brainstorm potential holidays for freedom.

- Vote on one holiday.

- Collaboratively write a proposal to a local or state legislator or create a social media campaign to get this day recognized as a public holiday (see High School Play Honors Students Who Fought For MLK Holiday for inspiration).

Learning Resources

2. UNCOVER: Harriet Tubman, William Still, and the Underground Railroad

"The Underground Railroad was a system of safe houses and hiding places that helped fugitive slaves escape to freedom in Canada, Mexico, and elsewhere outside of the United States" (Ohio History Central, para. 1).

Its path to freedom was long and dangerous. It is estimated that 100,000 slaves gained freedom, however, that was only a small percentage of the more than 4 million enslaved black people in the South. Henry Louis Gates puts the number lower, ate between 25,000 and 40,000.

In Who Really Ran the Underground Railroad? Gates also addresses a series of myths that have emerged about the railroad, concluding that "it did succeed in aiding thousands of brave slaves, each of whom we should remember as heroes of African-American history, but not nearly as many as we commonly imagine, and most certainly not enough."

The Underground Railroad, Charles Webber, 1893, Public Domain

The Underground Railroad, Charles Webber, 1893, Public DomainHarriet Tubman was an escaped slave who became a “conductor” on the Underground Railroad, risking her life many times to help slaves gain freedom. Of her efforts, she said, “I can say what most conductors can’t say. I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger” (quoted in Library of Congress, nd).

Harriet Tubman, c. 1868-1869, Public Domain

Harriet Tubman, c. 1868-1869, Public DomainYou can learn more about Harriet Tubman on the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Women of the Abolitionist Movement.

William Still's role in the Underground Railroad is less well-known, but also compellingly important. A Free-Black businessman and abolitionist living in Philadelphia was responsible for helping Blacks who escaped to the city in the 1840s (William Still's National Significance).

William Still directed a network of people and places that enabled hundreds of Blacks to get to freedom in Canada. His book, The Underground Railroad (1872) was the only first-person account written and self-published by an African American.

Media Literacy Connections: Civil War News Stories and Recruitment Advertisements

In an interview with Ken Burns, the historian Stephen B. Oates called the Civil War the "great central experience" of United States history (1989, para 14). The Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution promised liberty and justice for all, but Black slavery in southern states contradicted and undermined those values and questioned the survival of democracy as a form government.

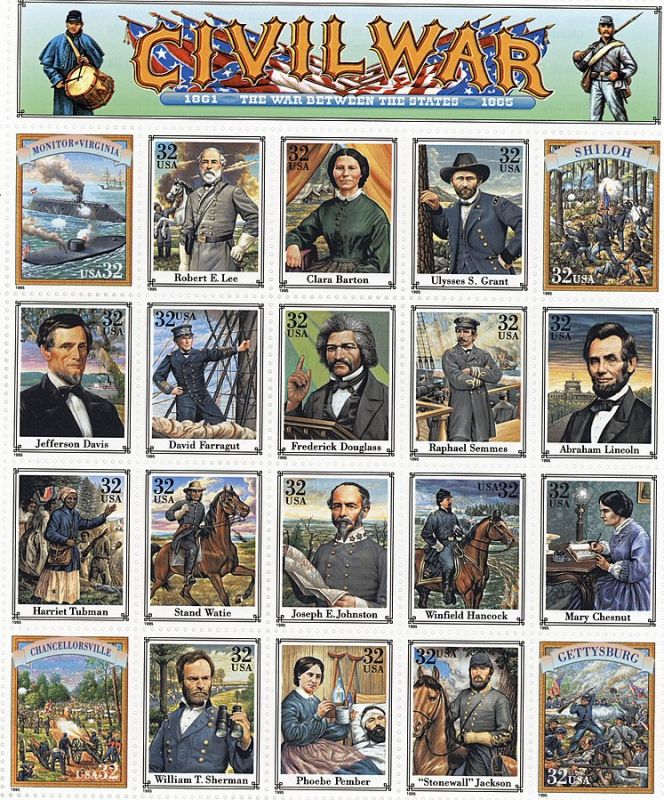

A sheet of US 32-cent postage stamps commemorating the American Civil War/War Between the States | Public Domain

A sheet of US 32-cent postage stamps commemorating the American Civil War/War Between the States | Public DomainIn many ways, the Civil War is still with us as a nation today. Black Americans still seek equality under the law. Racism toward Black people still permeates through all aspects of society. Conservative white politicians in red states seek to limit the political participation and voting of people of color. In 1968, the Kerner Commission declared "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white - separate and unequal" (para. 2). That reality remains true in the third decade of the 21st century.

To understand the present, it is important to understand the past, and these activities explore different dimensions of the Civil War and its impacts on civil rights through the lens of newspapers and advertisements:

Suggested Learning Activities

- Design a Timeline or Tell a Visual Story

Online Resources for Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad

3. Engage: Whose Faces or Images Should Be on U.S. Currency?

"Who has the "right face" for America?" asks University of Houston professor Karen Fang (2022) in her essay about Asian and African American stereotypes from the 1800s to the present day. Analyzing historical and current movie posters, political cartoons, advertising illustrations, and other media publications, Fang demonstrates how widely-circulated stereotypes have long demeaned and dehumanized Black and Brown people.

Yet African American, Asian American, and other marginalized groups are central parts of U.S. history and the American story. Changing how people are represented from the racist images of the past to more realistic and affirming portrayls is, for Fang, "a crucial part of changing how we think about -- and treat -- Americans of all ethnicties."

Fang's call for new representations of people in media raises questions about whose faces and images should be shown on U.S. currency (both paper bills and coins). In 2016, the Treasury Department announced plans to redesign the $5, $10, and $20 dollar bills to honor historical figures involved in women’s suffrage or the civil rights movement. Five Presidents and two founding fathers are currently displayed on paper bills.

Image from Pixabay

The Treasury Department’s plans for new images for the $10 focused on women’s suffrage advocates Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Alice Paul.

The focus for the $5 was to be on individuals who were part of seminal events that occurred at the Lincoln Memorial, such as singer Marian Anderson and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Harriet Tubman was to be the first new image appearing on the $20 dollar bill, but that plan has been delayed to 2028 by the Secretary of the Treasury in 2019. The Treasury Secretary does have the authority to decide whose face can appear on every U.S. bill.

Beginning in 2022 and continuing through 2025, the U.S. Mint will implement the American Women Quarters Program honoring the accomplishments of women in US history. Maya Angelou and Sally Ride will be the first to appear on coins.

Who do you believe should be represented on paper bills or coins? Why?

Media Literacy Connections: Representations of Gender and Race on Currency

The proposal to include Harriet Tubman on the $20 bill and Maya Angelou and Sally Ride on quarters opens an important topic for critical media analysis.

Given their constant use, the images on banknotes and coins become part of everyone's accepted stock of knowledge. We take for granted that George Washington looked like just he appears on the $1 bill, Alexander Hamilton like he does on the $10 bill, and so on. At the same time, the vast majority of images on U.S. money have been of White men, conveying a message that women and people of color are less deserving of the honor of currency recognition.

The history of women and people of color on currency are largely untold stories. Since World War I, women have appeared only on coins, namely Susan B. Anthony, Sacagawea, and Helen Keller. Martha Washington appeared on $1 silver certificates in 1886 and Pocahontas on the $20 bill in the 1860s. Booker T. Washington was the first African American on a coin in 1946; Jackie Robinson, Duke Ellington, Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King, and the Tuskegee Airmen, among others have appeared since then. A Native American figure appeared on the Indian Head penny, but the model was a liberty lady wearing an Native American head-dress; only a few million Buffalo nickels were minted in the early 20th century.

In these activities, you will analyze how women and people of color have been displayed on currency before proposing new images that suggest their importance and impact on American society and culture:

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSuggested Learning Activity

- Engage in Civic Action

- Propose a New Design for U.S. Currency

- Review the following article: "Who, What, Why: How do you get your face on the dollar?"

- What new images honoring individuals who fought for civil rights would you propose for U. S. paper currency?

- Note: Current law prohibits any living person from appearing on U.S. currency

- Give the name of the person, the rationale for the selection, and a proposed design for the currency (including the front and back of the currency). Use the list below (current image is in brackets).

- $ 1 dollar bill (George Washington)

- $ 2 dollar bill (Thomas Jefferson)

- $ 5 dollar bill (Abraham Lincoln)

- $ 10 dollar bill (Alexander Hamilton)

- $ 20 dollar bill (Andrew Jackson)

- $ 50 dollar bill (Ulysses S. Grant)

- $ 100 dollar bill (Benjamin Franklin)

Link to the table.

Standard 5.3 Conclusion

The Civil War is at the center of the constitutional history of the United States. Before the war, the institution of slavery was a glaring contradiction in American government and society. How could there be slavery in the country founded on the principle that all men are free? After the war, black Americans have struggled for equal rights for more than 150 years and continue to do so today. INVESTIGATE looked at three topics that shaped the Civil War era. UNCOVER told the story of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. ENGAGE asked that given the Civil War and African American struggles for freedom, whose faces should appear on United States currency.