Dalton’s law of partial pressures may be used to relate measured gas pressures for gaseous mixtures to their compositions. Diffusion is the process whereby gaseous atoms and molecules are transferred from regions of relatively high concentration to regions of relatively low concentration. Effusion is a similar process in which gaseous species pass from a container to a vacuum through very small orifices. The rates of effusion of gases are inversely proportional to the square roots of their densities or to the square roots of their atoms/molecules’ masses (Graham’s law). The concentration of a gaseous solute in a solution is proportional to the partial pressure of the gas to which the solution is exposed, a relation known as Henry’s law.

25.1 The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases: Dalton’s Law

Learning Objectives

- State Dalton’s law of partial pressures and use it in calculations involving gaseous mixtures

Unless they chemically react with each other, the individual gases in a mixture of gases do not affect each other’s pressure. Each individual gas in a mixture exerts the same pressure that it would exert if it were present alone in the container (Figure 25.1). The pressure exerted by each individual gas in a mixture is called its partial pressure. This observation is summarized by Dalton’s law of partial pressures: The total pressure of a mixture of ideal gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the component gases:

In the equation PTotal is the total pressure of a mixture of gases, PA is the partial pressure of gas A; PB is the partial pressure of gas B; PC is the partial pressure of gas C; and so on.

The partial pressure of gas A is related to the total pressure of the gas mixture via its mole fraction (X), a unit of concentration defined as the number of moles of a component of a solution divided by the total number of moles of all components:

where PA, XA, and nA are the partial pressure, mole fraction, and number of moles of gas A, respectively, and nTotal is the number of moles of all components in the mixture.

The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases

A 10.0-L vessel contains 2.50

10

−3 mol of H

2, 1.00

10

−3 mol of He, and 3.00

10

−4 mol of Ne at 35 °C.

(a) What are the partial pressures of each of the gases?

(b) What is the total pressure in atmospheres?

Solution

The gases behave independently, so the partial pressure of each gas can be determined from the ideal gas equation, using

:

The total pressure is given by the sum of the partial pressures:

Check Your Learning

A 5.73-L flask at 25 °C contains 0.0388 mol of N

2, 0.147 mol of CO, and 0.0803 mol of H

2. What is the total pressure in the flask in atmospheres?

Here is another example of this concept, but dealing with mole fraction calculations.

The Pressure of a Mixture of Gases

A gas mixture used for anesthesia contains 2.83 mol oxygen, O

2, and 8.41 mol nitrous oxide, N

2O. The total pressure of the mixture is 192 kPa.

(a) What are the mole fractions of O2 and N2O?

(b) What are the partial pressures of O2 and N2O?

Solution

The mole fraction is given by

and the partial pressure is

PA =

XA PTotal.

For O2,

and

For N2O,

and

Check Your Learning

What is the pressure of a mixture of 0.200 g of H

2, 1.00 g of N

2, and 0.820 g of Ar in a container with a volume of 2.00 L at 20 °C?

Collection of Gases over Water

A simple way to collect gases that do not react with water is to capture them in a bottle that has been filled with water and inverted into a dish filled with water. The pressure of the gas inside the bottle can be made equal to the air pressure outside by raising or lowering the bottle. When the water level is the same both inside and outside the bottle (Figure 25.2), the pressure of the gas is equal to the atmospheric pressure, which can be measured with a barometer.

However, there is another factor we must consider when we measure the pressure of the gas by this method. Water evaporates and there is always gaseous water (water vapor) above a sample of liquid water. As a gas is collected over water, it becomes saturated with water vapor and the total pressure of the mixture equals the partial pressure of the gas plus the partial pressure of the water vapor. The pressure of the pure gas is therefore equal to the total pressure minus the pressure of the water vapor—this is referred to as the “dry” gas pressure, that is, the pressure of the gas only, without water vapor. The vapor pressure of water, which is the pressure exerted by water vapor in equilibrium with liquid water in a closed container, depends on the temperature (Figure 25.3); more detailed information on the temperature dependence of water vapor can be found in Table 25.1, and vapor pressure will be discussed in more detail in the chapter on liquids.

Table 25.1

Vapor Pressure of Ice and Water in Various Temperatures at Sea Level

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) | | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) | | Temperature (°C) | Pressure (torr) |

|---|

| –10 | 1.95 | | 18 | 15.5 | | 30 | 31.8 |

| –5 | 3.0 | 19 | 16.5 | 35 | 42.2 |

| –2 | 3.9 | 20 | 17.5 | 40 | 55.3 |

| 0 | 4.6 | 21 | 18.7 | 50 | 92.5 |

| 2 | 5.3 | 22 | 19.8 | 60 | 149.4 |

| 4 | 6.1 | 23 | 21.1 | 70 | 233.7 |

| 6 | 7.0 | 24 | 22.4 | 80 | 355.1 |

| 8 | 8.0 | 25 | 23.8 | 90 | 525.8 |

| 10 | 9.2 | 26 | 25.2 | 95 | 633.9 |

| 12 | 10.5 | 27 | 26.7 | 99 | 733.2 |

| 14 | 12.0 | 28 | 28.3 | 100.0 | 760.0 |

| 16 | 13.6 | 29 | 30.0 | 101.0 | 787.6 |

Pressure of a Gas Collected Over Water

If 0.200 L of argon is collected over water at a temperature of 26 °C and a pressure of 750 torr in a system like that shown in

Figure 25.2, what is the partial pressure of argon?

Solution

According to Dalton’s law, the total pressure in the bottle (750 torr) is the sum of the partial pressure of argon and the partial pressure of gaseous water:

Rearranging this equation to solve for the pressure of argon gives:

The pressure of water vapor above a sample of liquid water at 26 °C is 25.2 torr, so:

Check Your Learning

A sample of oxygen collected over water at a temperature of 29.0 °C and a pressure of 764 torr has a volume of 0.560 L. What volume would the dry oxygen have under the same conditions of temperature and pressure?

Avogadro’s Law Revisited

All gases that show ideal behavior contain the same number of molecules in the same volume (at the same temperature and pressure). Thus, the ratios of volumes of gases involved in a chemical reaction are given by the coefficients in the equation for the reaction, provided that the gas volumes are measured at the same temperature and pressure.

We can extend Avogadro’s law (that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to the number of moles of the gas) to chemical reactions with gases: Gases combine, or react, in definite and simple proportions by volume, provided that all gas volumes are measured at the same temperature and pressure. For example, since nitrogen and hydrogen gases react to produce ammonia gas according to a given volume of nitrogen gas reacts with three times that volume of hydrogen gas to produce two times that volume of ammonia gas, if pressure and temperature remain constant.

The explanation for this is illustrated in Figure 25.4. According to Avogadro’s law, equal volumes of gaseous N2, H2, and NH3, at the same temperature and pressure, contain the same number of molecules. Because one molecule of N2 reacts with three molecules of H2 to produce two molecules of NH3, the volume of H2 required is three times the volume of N2, and the volume of NH3 produced is two times the volume of N2.

Reaction of Gases

Propane, C

3H

8(

g), is used in gas grills to provide the heat for cooking. What volume of O

2(

g) measured at 25 °C and 760 torr is required to react with 2.7 L of propane measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure? Assume that the propane undergoes complete combustion.

Solution

The ratio of the volumes of C

3H

8 and O

2 will be equal to the ratio of their coefficients in the balanced equation for the reaction:

From the equation, we see that one volume of C3H8 will react with five volumes of O2:

A volume of 13.5 L of O2 will be required to react with 2.7 L of C3H8.

Check Your Learning

An acetylene tank for an oxyacetylene welding torch provides 9340 L of acetylene gas, C

2H

2, at 0 °C and 1 atm. How many tanks of oxygen, each providing 7.00

10

3 L of O

2 at 0 °C and 1 atm, will be required to burn the acetylene?

3.34 tanks (2.34 104 L)

Volumes of Reacting Gases

Ammonia is an important fertilizer and industrial chemical. Suppose that a volume of 683 billion cubic feet of gaseous ammonia, measured at 25 °C and 1 atm, was manufactured. What volume of H

2(

g), measured under the same conditions, was required to prepare this amount of ammonia by reaction with N

2?

Solution

Because equal volumes of H

2 and NH

3 contain equal numbers of molecules and each three molecules of H

2 that react produce two molecules of NH

3, the ratio of the volumes of H

2 and NH

3 will be equal to 3:2. Two volumes of NH

3, in this case in units of billion ft

3, will be formed from three volumes of H

2:

The manufacture of 683 billion ft3 of NH3 required 1020 billion ft3 of H2. (At 25 °C and 1 atm, this is the volume of a cube with an edge length of approximately 1.9 miles.)

Check Your Learning

What volume of O

2(

g) measured at 25 °C and 760 torr is required to react with 17.0 L of ethylene, C

2H

4(

g), measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure? The products are CO

2 and water vapor.

Volume of Gaseous Product

What volume of hydrogen at 27 °C and 723 torr may be prepared by the reaction of 8.88 g of gallium with an excess of hydrochloric acid?

Solution

Convert the provided mass of the limiting reactant, Ga, to moles of hydrogen produced:

Convert the provided temperature and pressure values to appropriate units (K and atm, respectively), and then use the molar amount of hydrogen gas and the ideal gas equation to calculate the volume of gas:

Check Your Learning

Sulfur dioxide is an intermediate in the preparation of sulfuric acid. What volume of SO

2 at 343 °C and 1.21 atm is produced by burning l.00 kg of sulfur in excess oxygen?

How Sciences Interconnect

Greenhouse Gases and Climate Change

The thin skin of our atmosphere keeps the earth from being an ice planet and makes it habitable. In fact, this is due to less than 0.5% of the air molecules. Of the energy from the sun that reaches the earth, almost is reflected back into space, with the rest absorbed by the atmosphere and the surface of the earth. Some of the energy that the earth absorbs is re-emitted as infrared (IR) radiation, a portion of which passes back out through the atmosphere into space. Most of this IR radiation, however, is absorbed by certain atmospheric gases, effectively trapping heat within the atmosphere in a phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect. This effect maintains global temperatures within the range needed to sustain life on earth. Without our atmosphere, the earth's average temperature would be lower by more than 30 °C (nearly 60 °F). The major greenhouse gases (GHGs) are water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane, and ozone. Since the Industrial Revolution, human activity has been increasing the concentrations of GHGs, which have changed the energy balance and are significantly altering the earth’s climate (Figure 25.5).

There is strong evidence from multiple sources that higher atmospheric levels of CO2 are caused by human activity, with fossil fuel burning accounting for about of the recent increase in CO2. Reliable data from ice cores reveals that CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is at the highest level in the past 800,000 years; other evidence indicates that it may be at its highest level in 20 million years. In recent years, the CO2 concentration has increased from preindustrial levels of ~280 ppm to more than 400 ppm today (Figure 25.6).

Watch this video that explains greenhouse gases and global warming:

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSusan Solomon

Atmospheric and climate scientist Susan Solomon (Figure 25.7) is the author of one of The New York Times books of the year (The Coldest March, 2001), one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world (2008), and a working group leader of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was the recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. She helped determine and explain the cause of the formation of the ozone hole over Antarctica, and has authored many important papers on climate change. She has been awarded the top scientific honors in the US and France (the National Medal of Science and the Grande Medaille, respectively), and is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, the Royal Society, the French Academy of Sciences, and the European Academy of Sciences. Formerly a professor at the University of Colorado, she is now at MIT, and continues to work at NOAA.

For more information, watch this video about Susan Solomon:

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeLink to Supplemental Exercises

Supplemental exercises are available if you would like more practice with these concepts.

25.2 Effusion and Diffusion of Gases

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define and explain effusion and diffusion

- State Graham’s law and use it to compute relevant gas properties

If you have ever been in a room when a piping hot pizza was delivered, you have been made aware of the fact that gaseous molecules can quickly spread throughout a room, as evidenced by the pleasant aroma that soon reaches your nose. Although gaseous molecules travel at tremendous speeds (hundreds of meters per second), they collide with other gaseous molecules and travel in many different directions before reaching the desired target. At room temperature, a gaseous molecule will experience billions of collisions per second. The mean free path is the average distance a molecule travels between collisions. The mean free path increases with decreasing pressure; in general, the mean free path for a gaseous molecule will be hundreds of times the diameter of the molecule

In general, we know that when a sample of gas is introduced to one part of a closed container, its molecules very quickly disperse throughout the container; this process by which molecules disperse in space in response to differences in concentration is called diffusion (shown in Figure 25.8). The gaseous atoms or molecules are, of course, unaware of any concentration gradient, they simply move randomly—regions of higher concentration have more particles than regions of lower concentrations, and so a net movement of species from high to low concentration areas takes place. In a closed environment, diffusion will ultimately result in equal concentrations of gas throughout, as depicted in Figure 25.8. The gaseous atoms and molecules continue to move, but since their concentrations are the same in both bulbs, the rates of transfer between the bulbs are equal (no net transfer of molecules occurs).

We are often interested in the rate of diffusion, the amount of gas passing through some area per unit time:

The diffusion rate depends on several factors: the concentration gradient (the increase or decrease in concentration from one point to another); the amount of surface area available for diffusion; and the distance the gas particles must travel. Note also that the time required for diffusion to occur is inversely proportional to the rate of diffusion, as shown in the rate of diffusion equation.

A process involving movement of gaseous species similar to diffusion is effusion, the escape of gas molecules through a tiny hole such as a pinhole in a balloon into a vacuum (Figure 25.9). Although diffusion and effusion rates both depend on the molar mass of the gas involved, their rates are not equal; however, the ratios of their rates are the same.

If a mixture of gases is placed in a container with porous walls, the gases effuse through the small openings in the walls. The lighter gases pass through the small openings more rapidly (at a higher rate) than the heavier ones (Figure 25.10). In 1832, Thomas Graham studied the rates of effusion of different gases and formulated Graham’s law of effusion: The rate of effusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of the mass of its particles:

This means that if two gases A and B are at the same temperature and pressure, the ratio of their effusion rates is inversely proportional to the ratio of the square roots of the masses of their particles:

Applying Graham’s Law to Rates of Effusion

Calculate the ratio of the rate of effusion of hydrogen to the rate of effusion of oxygen.

Solution

From Graham’s law, we have:

Hydrogen effuses four times as rapidly as oxygen.

Check Your Learning

At a particular pressure and temperature, nitrogen gas effuses at the rate of 79 mL/s. Under the same conditions, at what rate will sulfur dioxide effuse?

Effusion Time Calculations

It takes 243 s for 4.46

10

−5 mol Xe to effuse through a tiny hole. Under the same conditions, how long will it take 4.46

10

−5 mol Ne to effuse?

Solution

It is important to resist the temptation to use the times directly, and to remember how rate relates to time as well as how it relates to mass. Recall the definition of rate of effusion:

and combine it with Graham’s law:

To get:

Noting that amount of A = amount of B, and solving for time for Ne:

and substitute values:

Finally, solve for the desired quantity:

Note that this answer is reasonable: Since Ne is lighter than Xe, the effusion rate for Ne will be larger than that for Xe, which means the time of effusion for Ne will be smaller than that for Xe.

Check Your Learning

A party balloon filled with helium deflates to

of its original volume in 8.0 hours. How long will it take an identical balloon filled with the same number of moles of air (ℳ = 28.2 g/mol) to deflate to

of its original volume?

Determining Molar Mass Using Graham’s Law

An unknown gas effuses 1.66 times more rapidly than CO

2. What is the molar mass of the unknown gas? Can you make a reasonable guess as to its identity?

Solution

From Graham’s law, we have:

Plug in known data:

Solve:

The gas could well be CH4, the only gas with this molar mass.

Check Your Learning

Hydrogen gas effuses through a porous container 8.97-times faster than an unknown gas. Estimate the molar mass of the unknown gas.

How Sciences Interconnect

Use of Diffusion for Nuclear Energy Applications: Uranium Enrichment

Gaseous diffusion has been used to produce enriched uranium for use in nuclear power plants and weapons. Naturally occurring uranium contains only 0.72% of 235U, the kind of uranium that is “fissile,” that is, capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. Nuclear reactors require fuel that is 2–5% 235U, and nuclear bombs need even higher concentrations. One way to enrich uranium to the desired levels is to take advantage of Graham’s law. In a gaseous diffusion enrichment plant, uranium hexafluoride (UF6, the only uranium compound that is volatile enough to work) is slowly pumped through large cylindrical vessels called diffusers, which contain porous barriers with microscopic openings. The process is one of diffusion because the other side of the barrier is not evacuated. The 235UF6 molecules have a higher average speed and diffuse through the barrier a little faster than the heavier 238UF6 molecules. The gas that has passed through the barrier is slightly enriched in 235UF6 and the residual gas is slightly depleted. The small difference in molecular weights between 235UF6 and 238UF6 only about 0.4% enrichment, is achieved in one diffuser (Figure 25.11). But by connecting many diffusers in a sequence of stages (called a cascade), the desired level of enrichment can be attained.

The large scale separation of gaseous 235UF6 from 238UF6 was first done during the World War II, at the atomic energy installation in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, as part of the Manhattan Project (the development of the first atomic bomb). Although the theory is simple, this required surmounting many daunting technical challenges to make it work in practice. The barrier must have tiny, uniform holes (about 10–6 cm in diameter) and be porous enough to produce high flow rates. All materials (the barrier, tubing, surface coatings, lubricants, and gaskets) need to be able to contain, but not react with, the highly reactive and corrosive UF6.

Because gaseous diffusion plants require very large amounts of energy (to compress the gas to the high pressures required and drive it through the diffuser cascade, to remove the heat produced during compression, and so on), it is now being replaced by gas centrifuge technology, which requires far less energy. A current hot political issue is how to deny this technology to Iran, to prevent it from producing enough enriched uranium for them to use to make nuclear weapons.

Link to Supplemental Exercises

Supplemental exercises are available if you would like more practice with these concepts.

25.3 Solubility

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the effects of temperature and pressure on solubility

- State Henry’s law and use it in calculations involving the solubility of a gas in a liquid

Imagine adding a small amount of sugar to a glass of water, stirring until all the sugar has dissolved, and then adding a bit more. You can repeat this process until the sugar concentration of the solution reaches its natural limit, a limit determined primarily by the relative strengths of the solute-solute, solute-solvent, and solvent-solvent attractive forces discussed in the previous two modules of this chapter. You can be certain that you have reached this limit because, no matter how long you stir the solution, undissolved sugar remains. The concentration of sugar in the solution at this point is known as its solubility.

The solubility of a solute in a particular solvent is the maximum concentration that may be achieved under given conditions when the dissolution process is at equilibrium.

When a solute’s concentration is equal to its solubility, the solution is said to be saturated with that solute. If the solute’s concentration is less than its solubility, the solution is said to be unsaturated. A solution that contains a relatively low concentration of solute is called dilute, and one with a relatively high concentration is called concentrated.

Use this interactive simulation to prepare various saturated solutions.

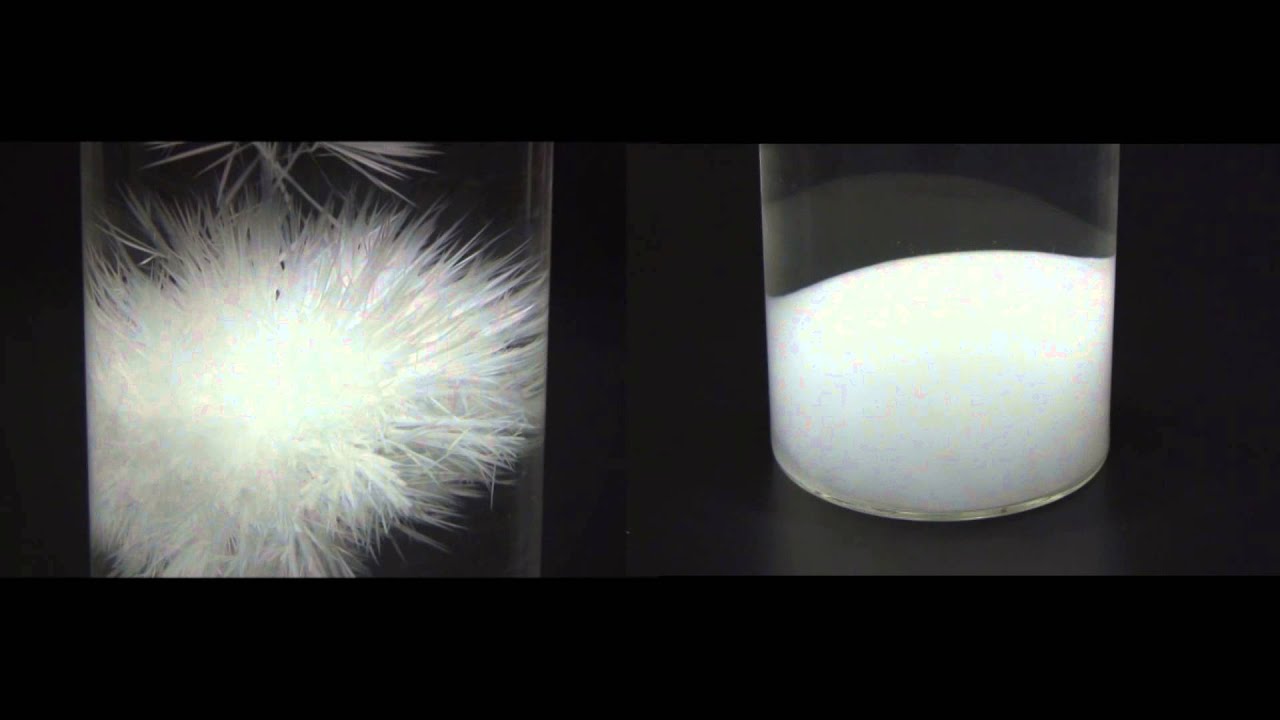

Solutions may be prepared in which a solute concentration exceeds its solubility. Such solutions are said to be supersaturated, and they are interesting examples of nonequilibrium states (a detailed treatment of this important concept is provided in the text chapters on equilibrium). For example, the carbonated beverage in an open container that has not yet “gone flat” is supersaturated with carbon dioxide gas; given time, the CO2 concentration will decrease until it reaches its solubility.

Watch this impressive video showing the precipitation of sodium acetate from a supersaturated solution.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSolutions of Gases in Liquids

As for any solution, the solubility of a gas in a liquid is affected by the intermolecular attractive forces between solute and solvent species. Unlike solid and liquid solutes, however, there is no solute-solute intermolecular attraction to overcome when a gaseous solute dissolves in a liquid solvent since the atoms or molecules comprising a gas are far separated and experience negligible interactions. Consequently, solute-solvent interactions are the sole energetic factor affecting solubility. For example, the water solubility of oxygen is approximately three times greater than that of helium (there are greater dispersion forces between water and the larger oxygen molecules) but 100 times less than the solubility of chloromethane, CHCl3 (polar chloromethane molecules experience dipole–dipole attraction to polar water molecules). Likewise note the solubility of oxygen in hexane, C6H14, is approximately 20 times greater than it is in water because greater dispersion forces exist between oxygen and the larger hexane molecules.

Temperature is another factor affecting solubility, with gas solubility typically decreasing as temperature increases (Figure 25.12). This inverse relation between temperature and dissolved gas concentration is responsible for one of the major impacts of thermal pollution in natural waters.

When the temperature of a river, lake, or stream is raised, the solubility of oxygen in the water is decreased. Decreased levels of dissolved oxygen may have serious consequences for the health of the water’s ecosystems and, in severe cases, can result in large-scale fish kills (Figure 25.13).

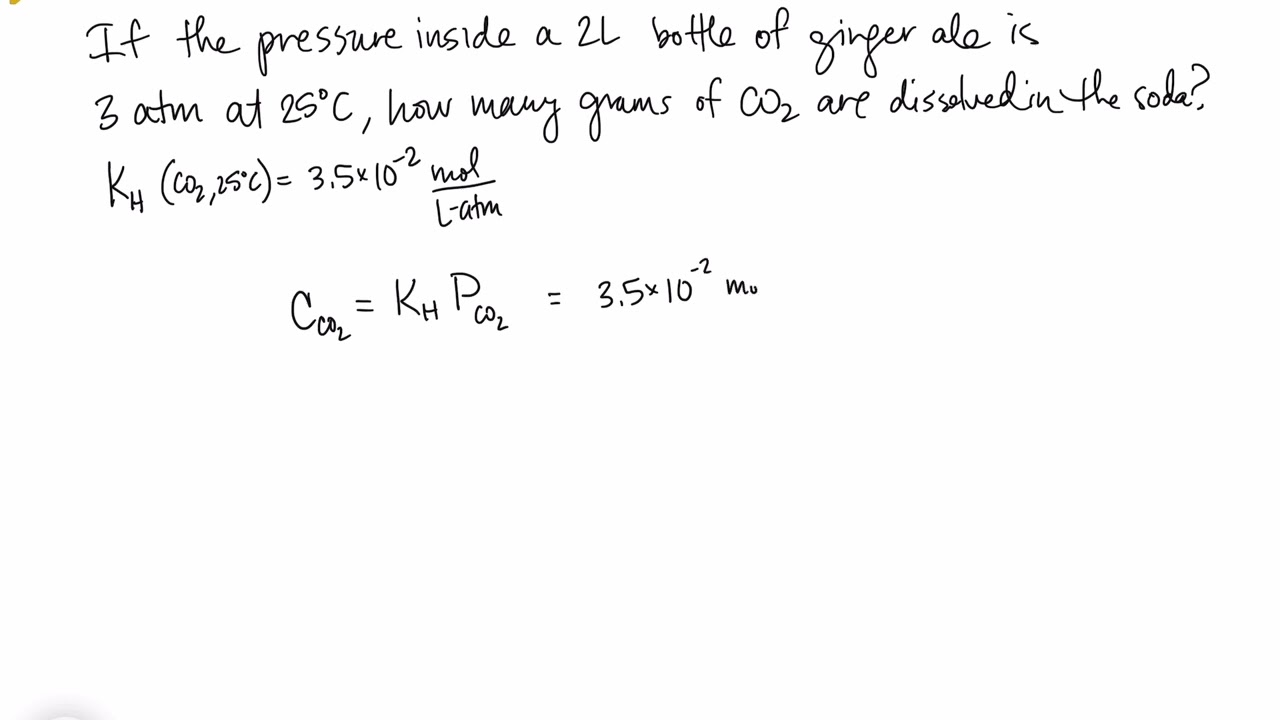

The solubility of a gaseous solute is also affected by the partial pressure of solute in the gas to which the solution is exposed. Gas solubility increases as the pressure of the gas increases. Carbonated beverages provide a nice illustration of this relationship. The carbonation process involves exposing the beverage to a relatively high pressure of carbon dioxide gas and then sealing the beverage container, thus saturating the beverage with CO2 at this pressure. When the beverage container is opened, a familiar hiss is heard as the carbon dioxide gas pressure is released, and some of the dissolved carbon dioxide is typically seen leaving solution in the form of small bubbles (Figure 25.14). At this point, the beverage is supersaturated with carbon dioxide and, with time, the dissolved carbon dioxide concentration will decrease to its equilibrium value and the beverage will become “flat.”

For many gaseous solutes, the relation between solubility, Cg, and partial pressure, Pg, is a proportional one:

where k is a proportionality constant that depends on the identity of the gaseous solute, the identity of the solvent, and the solution temperature. This is a mathematical statement of Henry’s law: The quantity of an ideal gas that dissolves in a definite volume of liquid is directly proportional to the pressure of the gas.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

Application of Henry’s Law

At 20 °C, the concentration of dissolved oxygen in water exposed to gaseous oxygen at a partial pressure of 101.3 kPa is 1.38

10

−3 mol L

−1. Use Henry’s law to determine the solubility of oxygen when its partial pressure is 20.7 kPa, the approximate pressure of oxygen in earth’s atmosphere.

Solution

According to Henry’s law, for an ideal solution the solubility,

Cg, of a gas (1.38

10

−3 mol L

−1, in this case) is directly proportional to the pressure,

Pg, of the undissolved gas above the solution (101.3 kPa in this case). Because both

Cg and

Pg are known, this relation can be rearranged and used to solve for

k.

Now, use k to find the solubility at the lower pressure.

Note that various units may be used to express the quantities involved in these sorts of computations. Any combination of units that yield to the constraints of dimensional analysis are acceptable.

Check Your Learning

Exposing a 100.0 mL sample of water at 0 °C to an atmosphere containing a gaseous solute at 152 torr resulted in the dissolution of 1.45

10

−3 g of the solute. Use Henry’s law to determine the solubility of this gaseous solute when its pressure is 760 torr.

7.25 10−3 in 100.0 mL or 0.0725 g/L

Thermal Pollution and Oxygen Solubility

A certain species of freshwater trout requires a dissolved oxygen concentration of 7.5 mg/L. Could these fish thrive in a thermally polluted mountain stream (water temperature is 30.0 °C, partial pressure of atmospheric oxygen is 0.17 atm)? Use the data in

Figure 25.12 to estimate a value for the Henry's law constant at this temperature.

Solution

First, estimate the Henry’s law constant for oxygen in water at the specified temperature of 30.0 °C (

Figure 25.12 indicates the solubility at this temperature is approximately ~1.2 mol/L).

Then, use this k value to compute the oxygen solubility at the specified oxygen partial pressure, 0.17 atm.

Finally, convert this dissolved oxygen concentration from mol/L to mg/L.

This concentration is lesser than the required minimum value of 7.5 mg/L, and so these trout would likely not thrive in the polluted stream.

Check Your Learning

What dissolved oxygen concentration is expected for the stream above when it returns to a normal summer time temperature of 15 °C?

Chemistry in Everyday Life

Decompression Sickness or “The Bends”

Decompression sickness (DCS), or “the bends,” is an effect of the increased pressure of the air inhaled by scuba divers when swimming underwater at considerable depths. In addition to the pressure exerted by the atmosphere, divers are subjected to additional pressure due to the water above them, experiencing an increase of approximately 1 atm for each 10 m of depth. Therefore, the air inhaled by a diver while submerged contains gases at the corresponding higher ambient pressure, and the concentrations of the gases dissolved in the diver’s blood are proportionally higher per Henry’s law.

As the diver ascends to the surface of the water, the ambient pressure decreases and the dissolved gases becomes less soluble. If the ascent is too rapid, the gases escaping from the diver’s blood may form bubbles that can cause a variety of symptoms ranging from rashes and joint pain to paralysis and death. To avoid DCS, divers must ascend from depths at relatively slow speeds (10 or 20 m/min) or otherwise make several decompression stops, pausing for several minutes at given depths during the ascent. When these preventive measures are unsuccessful, divers with DCS are often provided hyperbaric oxygen therapy in pressurized vessels called decompression (or recompression) chambers (Figure 25.15). Researchers are also investigating related body reactions and defenses in order to develop better testing and treatment for decompression sicknetss. For example, Ingrid Eftedal, a barophysiologist specializing in bodily reactions to diving, has shown that white blood cells undergo chemical and genetic changes as a result of the condition; these can potentially be used to create biomarker tests and other methods to manage decompression sickness.

Deviations from Henry’s law are observed when a chemical reaction takes place between the gaseous solute and the solvent. Thus, for example, the solubility of ammonia in water increases more rapidly with increasing pressure than predicted by the law because ammonia, being a base, reacts to some extent with water to form ammonium ions and hydroxide ions.

Gases can form supersaturated solutions. If a solution of a gas in a liquid is prepared either at low temperature or under pressure (or both), then as the solution warms or as the gas pressure is reduced, the solution may become supersaturated. In 1986, more than 1700 people in Cameroon were killed when a cloud of gas, almost certainly carbon dioxide, bubbled from Lake Nyos (Figure 25.16), a deep lake in a volcanic crater. The water at the bottom of Lake Nyos is saturated with carbon dioxide by volcanic activity beneath the lake. It is believed that the lake underwent a turnover due to gradual heating from below the lake, and the warmer, less-dense water saturated with carbon dioxide reached the surface. Consequently, tremendous quantities of dissolved CO2 were released, and the colorless gas, which is denser than air, flowed down the valley below the lake and suffocated humans and animals living in the valley.