Standard 3.4: Elections and Nominations

Explain the process of elections in the legislative and executive branches and the process of nomination/confirmation of individuals in the judicial and executive branches. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T3.4]

FOCUS QUESTION: How Does the United States Conduct Elections and What Are Current Proposals for Reform?

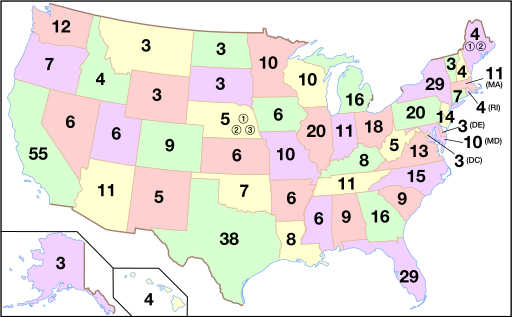

Electoral College Votes by States for the 2020 Election

Electoral College Votes by States for the 2020 Election

"Electoral map 2012-2020" by SeL | Public DomainIn 2020, the United States held its 59th Presidential election, a process that happens once every four years. There have been 46 Presidents from George Washington to Joe Biden, counting Grover Cleveland who was elected twice. John F. Kennedy was the youngest man elected to the office, although Theodore Roosevelt became the youngest President after the death of William McKinley. Franklin D. Roosevelt served the longest, 4,422 days; William Henry Harrison served the least amount of time, 31 days. At age 78, Biden is the oldest man elected President.

Each state conducts its own separate election for President, giving the United States "arguably the most decentralized election administration of any advanced democracy" (Toobin, 2020b, p. 37). States organize how and when people will vote—either on a designated Election Day (the first Tuesday in November for federal contests), before that day by mail-in absentee ballot, or through specific state-approved early voting procedures. Toobin notes that there are some 10,500 different voting jurisdictions in the country, many with their own rules and procedures for casting and counting ballots.

In theory, free and fair elections that reflect the will of the people are a hallmark of American democracy. Yet as commentator Perry Bacon, Jr. (2021) has noted there are major structural features within the U.S. system for electing the President and members of Congress that make it less democratic, features that has help support the current political dominance of the Republican Party:

- First, the electoral college can negate the popular vote; in 2020, Donald Trump would have won a second term with just 270,000 more votes in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin despite Joe Biden winning more than 7 million more popular votes.

- Second, the requirement that there be 2 Senators for every state, irregardless of its population. In 2021, 50 Democratic senators represent 185 million people; 50 Republican senators represent 143 million.

- Third, the practice of gerrymandering has allowed political parties to shape state voting districts so that incumbents are more likely to win elections.

- Fourth, voters tend to vote along party lines irregardless of the issues being raised by candidates in political campaigns. In 2020, in only 16 out of 435 House districts did voters vote for one candidate for President from one party and another candidate for the House from the other party.

In contemporary elections "Democrats win more people, Republicans win more places," writes commentator Ezra Klein (2021). In the 2020 election, Joe Biden won 551 counties and 81 million votes; Donald Trump won 2,588 counties and 74 million votes. The result, notes Klein, is that while the Democrats have a national majority, Republicans have greater control at state and local levels.

How does the election system work and how might it be changed? The modules for this standard explore that question in terms of the electoral college, disputed elections in U.S. history, the possibility of a disrupted or delayed election in 2020, and calls for election reform, including a move to instant runoff/ranked choice voting.

The history and current efforts of voter suppression can be found in Topic 4.5 in this book.

1. INVESTIGATE: Presidential Elections, the Popular Vote, and the Electoral College

A popular vote is the vote cast by each individual voter in an election. Virtually all elections in the United States are won by the candidate who receives the most popular votes - except when electing the President.

In Presidential elections, people vote for a slate of electors who represent a candidate in the Electoral College. Each state's popular vote winner receives a designated number of electoral votes. The candidate with 270 or more electoral votes becomes President of the United States.

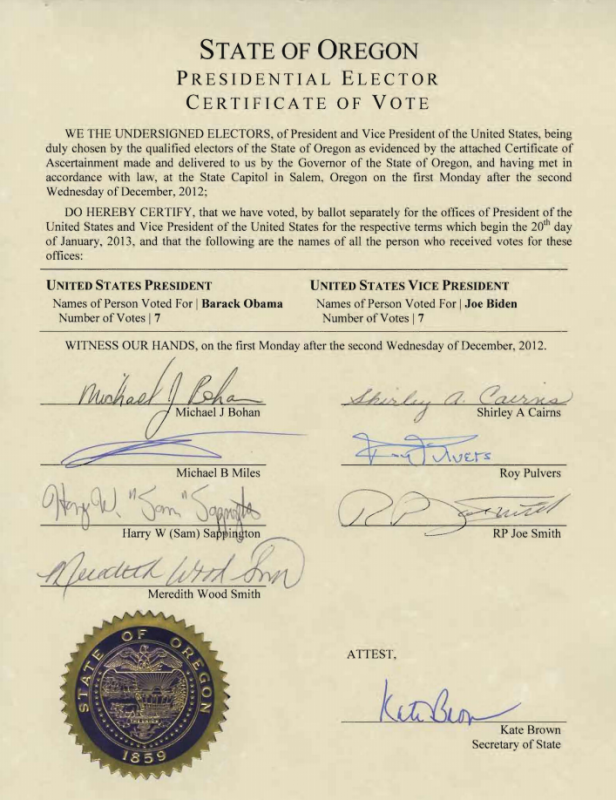

Oregon Electoral College 2012 Certificate of Vote | Public Domain

Oregon Electoral College 2012 Certificate of Vote | Public DomainThe Electoral College

The Electoral College is not an institution of higher education with a physical campus. Rather, it is a number of electoral votes assigned to each state equal to the number of representatives they have in the House of Representatives (as determined every ten years by the Census) plus two more for each of the state's two Senators. In addition, the District of Columbia has three electoral votes. This means there are presently 538 electors in the Electoral College.

States with the highest number of people living in them have most electoral votes. Following the 2020 Census, the states with the most electoral votes are California (54), Texas (40 electoral votes), Florida (30) and New York (28). States with small numbers of people have the fewest electoral votes: Alaska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming each have 3 electoral votes.

The Electoral College gives a greater electoral impact to states with a smaller numbers of people. California (with 54 electoral votes) has about 40 million residents while Alaska and Wyoming (each with 3 electoral votes) have less than one million residents (around 740,000 in Alaska and 578,000 in Wyoming). Doing the math as to the electoral college, voters in Alaska and Wyoming have more than 3 times the impact of a voter in California. If each California district had the same impact as Alaska or Wyoming, California would need to have 159 electoral votes.

The Electoral College has a fascinating history. It was created at the Constitutional Convention as a compromise between those who wanted Congress to choose the President and those who felt that decision should be done by state governments. As Michael Kazin (2020, p. 43) noted, "The system they came up with was nobody's first choice."

Recent Presidential elections have led to calls to abolish or substantially reform the Electoral College as an outdated institution that does not serve the interests of a democratic society. In 2016 Donald Trump won the Electoral College and the Presidency by a total of 77,744 votes in three states (Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin), a margin that amounted to one-twentieth of one percent of the 136 million votes cast in the election. You can see the complete 2016 national and state-by-state vote totals here.

Jesse Wegman in his book, Let the People Pick the President (2020) and New York Times columnist David Leonhardt ("The Electoral College and Democracy," 2020, December 14) have summarized two significant shortcomings of the Electoral College for democratic elections:

1) The Electoral College system can deny victory to the candidate who wins the popular vote as happened in the elections of 2016 (Trump/Clinton), 2000 (Bush/Gore), 1888 (Harrison/Cleveland), 1876 (Hayes/Tilden), and 1824 (Adams/Jackson). You can learn more at Disputed Elections in United States History.

2) Although it has not been done, it is constitutionally possible for states to change the rules about how to award electors, allowing those electors to vote for someone other than the state's popular vote winner.

Why has this undemocratic and largely unpopular institution survived? In Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? historian Alexander Keyssar (2020) recounts efforts to change the system, including 1968-69 when White southern segregationist senators barely blocked passage of an amendment to replace the Electoral College with a national popular vote for President. Historically speaking, efforts to overhaul or eliminate the Electoral College demonstrate the "particular difficulty–widespread in democracies—of altering electoral institutions once they are already in place" (Keyssar, 2020, p. 11).

Having the Electoral College as part of the United States system of government has brought the following features of American politics to the forefront, notably during 2000, 2016 and 2020 Presidential elections.

Special Topic Box: The 2020 Presidential Election: How Close Was It?

How close was the 2020 Presidential election? Some see it as a decisive victory for Joe Biden; others see it as a close race narrowly won by the Democratic Party. In fact, the 2020 Presidential Election was both not close and very close, a seemingly contradictory reality that reflects the uniqueness of the U.S. political system in which the Electoral College determines presidential winners.

It was not close. Joe Biden was elected nation’s 46th President with 81,283,098 votes (51.3%), Donald Trump received 74,222,958 (46.8%), and third party candidates the remaining 1.8% of 159,633,396 total votes cast. Two-thirds (66.7%) of the eligible voters voted, the largest voter turnout since 1900. In the past 6 Presidential elections, only Barack Obama won by a greater popular vote margin. It mattered that Biden was a Democrat; the Republican candidate has received a popular vote majority only once in the past two decades. Additionally, Biden won the crucial Electoral College vote 306 to 232.

It was very close. Despite trailing by more than 7 million popular votes and 74 electoral votes, if Donald Trump had received a few thousand more votes in three states (Arizona: 10,457; Georgia: 11,779; and Wisconsin: 20,682), then the election would have ended in a 269 to 269 electoral vote tie, the first since 1801 when the House of Representatives elected Thomas Jefferson president. Moreover, if Trump had won Nebraska’s Second Congressional District (Biden won 2 of the state’s 93 counties by just over 22,000 votes), he would have received 1 more electoral vote and been elected President outright. Nationally, Trump won 2496 counties to Biden’s 477 - except land does not vote, people do, and there were far more voters in the counties won by Biden than those won by Trump.

Do the results of the 2020 Presidential election change your view of the usefulness of the Electoral College for our country’s 21st century democracy? Why or Why Not?

Suggested Learning Activity

- Create a Curated Collection About the Electoral College

- Conduct Internet research to identify trustworthy, reliable, and accurate resources (e.g., news articles, videos, infographics, podcasts) about election results from the past three decades.

- Curate these resources into a Wakelet, Adobe Spark Page, or Google Site in a way that informs others about how the electoral college influences the outcome of Presidential elections.

- Bonus Points: Create your own resources (e.g., videos, images, podcasts) to add to the curated collection.

Additional Resources

Swing States and Spectator States

Swing states (also known as battleground states) are states be won by either major party in a Presidential election.

Spectator states are those states that consistently award their electoral votes to either the Democratic (e.g., Massachusetts, California, New York) or the Republican (e.g., Texas, Oklahoma, Montana) candidate.

Most states are spectator states in Presidential elections, while victory in swing states depends on the candidate. Barack Obama won Ohio in 2008 and 2012; Donald Trump won the state in 2016. No Republican candidate has ever won the White House without winning Ohio's electoral votes; since 1964, only Joe Biden as a Democratic candidate has won the Presidency without a victory in Ohio.

The status of states between swing and spectator is evolving. The FiveThirtyEight blog (Is the Election Map Changing? August 28, 2020) looked at how 16 swing or battleground states voted in the last 5 Presidential elections and found that Iowa and Ohio have moved more sharply Republican while Arizona moved toward the Democrats. In addition, while Maine and Michigan have moved away from the Democrats, Colorado and Virginia moved toward the Democrats. Florida and its 29 electoral votes remains a perennial swing state; every Presidential winner except Joe Biden since 1964 has won Florida.

Disputed Elections

In the electoral college system, the candidate with the most popular votes is not necessarily the winner, as was the case in the 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016 Presidential elections. UNCOVER: 2000 and Other Disputed Elections in U.S. History looks at this topic in more depth as does Disputed Elections in American Politics from the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki.

Disrupted or Delayed Elections

Can a Presidential election be delayed because of an emergency? At the end of July, 2020, President Trump, trailing badly in the polls, suggested delaying the November presidential election because of the coronavirus pandemic. Yet, only the states and the Congress have the constitutional authority to postpone voting or the meeting of the electoral college to choose the presidential and vice presidential winner (Does the Constitution Allow for a Delayed Presidential Election? National Constitution Center).

The only case of a postponed federal election happened in 2018 when a typhoon struck the Northern Mariana Islands 10 days before the election and the governor delayed both early and in-person election day voting. Primary elections have also been delayed by weather emergencies and after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks (Disrupted Federal Elections: Policy Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service).

Faithless Electors

Electoral College from the National Archives offers more information about how this feature of our government actually works, including the interesting concept of faithless electors, individuals who decide to vote for a candidate other than the one they were pledged to support. There have been only 90 faithless elector votes among the 23,507 electoral votes cast in 58 presidential elections - 63 of those in 1872 when unsuccessful candidate Horace Greeley died and 10 in the 2016 Trump/Clinton contest (Faithless Electors, FairVote, July 6, 2020). In 2020, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld state laws that remove, penalize, or cancel the votes of faithless electoral college delegates.

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact and Proportional Allocation of Electoral Votes

There are intense debates around what to do with the Electoral College. Many call for its elimination as an anti-democratic structure. These observers believe only a direct election by popular vote can accurately express the will of the people. Other commentators believe it is essential to keep the Electoral College in order to protect states with small populations. Without electoral votes, presidential candidates might tend to ignore small states because there are few popular votes to gain.

There are also proposals to keep the Electoral College, but change how it functions:

- The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is a growing agreement among states to award their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the most votes nationwide. It will take effect when states totalling 270 electoral votes sign on; to date states with 196 votes (including Massachusetts) have agreed as of July 2020 (Status of National Popular Vote Bill).

- Proportional Allocation of Electoral Votes means that instead of a winner-take-all system, electoral votes would be divided according to the percentage of popular votes that each candidate receives in a state.

- In 2000, for example, George W. Bush won Florida by 534 votes over Al Gore and received all the state's 25 electoral votes. If the electoral votes were distributed proportionally, Bush would have received 13 and Gore 12, giving the overall election to Gore. Here is how proportional allocation of electoral votes would affect the 2012 election on a state by state basis.

- You can link here to explore more ideas for Electoral College reform.

The Geography of States and the Electoral College

The number of electoral votes in the Electoral College are based on state population, but the boundaries of states have changed historically. Maine was once part of Massachusetts and West Virginia was once part of Virginia. The following interactive map from FiveThirtyEight blog looks at how the electoral votes would have changed in the 2016 election if the following rejected proposals for new states had been approved:

- Absaroka (portions of South Dakota, Wyoming, and Montana);

- Chicago (Cook County, Illinois as its own state);

- Deseret (Utah plus parts of California, Oregon, Idaho, and Wyoming);

- New York City (the city as its own state);

- Franklin (eastern Tennessee);

- Lincoln (eastern Washington state along with Idaho's panhandle);

- Old Massachusetts (Massachusetts and Maine combined);

- Original Virginia (Virginia and West Virginia combined); Pico (California split into two states at the 36th parallel);

- Republic of Texas (Texas as its own separate country);

- Superior (Michigan Upper Peninsula as a state); and

- Westsylvania (West Virginia with parts of Kentucky, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee).

Suggested Learning Activities

- Analyze Arguments For and Against: Should the United States continue to elect a President using the Electoral College?

- Supporting Direct Election - Many people call for the elimination of the Electoral College as an anti-democratic structure. These observers believe only a direct election by popular vote can accurately express the will of the people.

- Supporting the Electoral College - Other people believe it is essential to keep the Electoral College in order to ensure that states with small populations have relevance in national elections. Without electoral votes, presidential candidates might tend to ignore small states because there are few popular votes to gain.

- Resources

Online Resources for Presidential Elections and the Electoral College

Teacher-Designed Learning Plan: State Voting Patterns: Using History to Predict the Future

State Voting Patterns: Using History to Predict the Future is a learning activity developed by Amy Cyr, a 7th-grade social studies teacher in the Hampshire Regional School District in Westhampton, Massachusetts. This learning activity addresses the following standards:

- Massachusetts Grade 8: Topic 3/Standard 4

- Explain the process of elections in the legislative and executive branches and the process of nomination/confirmation of individuals in the judicial and executive branches.

- Advanced Placement (AP) United States Government and Politics

- Unit 5.8 - Electing a President

This learning plan can be adapted for in-person, virtual, or hybrid learning settings.

2. UNCOVER: 2000 and Other Disputed Elections in United States History

The 2000 Presidential election was a race between Al Gore, the Democratic candidate, George W. Bush, the Republican candidate, and Ralph Nader, the Green Party candidate (there were several other minor party candidates as well including Pat Buchanan running as a Reform Party candidate).

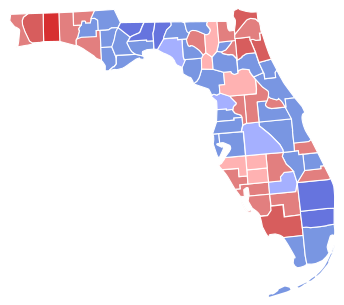

"Florida Senate Election Results by County, 2000" by Vartemp is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0

"Florida Senate Election Results by County, 2000" by Vartemp is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0The election was extremely close and even though Gore received a half-million more popular votes than Bush nationwide, Gore lost in the Electoral College when he lost the state of Florida by 537 popular votes out of nearly 6 million votes cast. Florida’s vote gave Bush 271 electoral votes, one over the required 270 to win the presidency - Al Gore finished with 266 electoral votes. It was the first election in 112 years in which a president lost the popular vote but won the electoral vote.

The 2000 election is one of five in U.S. history in which the "winner" received less popular votes but prevailed with a majority in the electoral college. It is one of six elections that historians consider to be “disputed elections.” Each disputed election raises interesting questions about the United States political system and the meaning of democratic elections.

Since 2000, evidence has been uncovered of multiple glaring irregularities which were never officially investigated and support the conclusion that Gore should have prevailed in Florida by a comfortable margin (The Bush-Gore Recount Is an Omen for 2020, The Atlantic, August 17, 2020). Thousands, if not tens of thousands of eligible voters were purged from the rolls in an overt move to disenfranchise African-Americans who overwhelmingly supported Gore. Voting machines in a district heavily populated by Jewish-Americans inexplicably tallied a large number of votes for Pat Buchanan, a man linked to innumerable antisemitic statements.

View the trailer for the movie RECOUNT, an HBO film starring Kevin Spacey and Dennis Leary that gives a dramatic look at the time following the announcement of Bush's victory in Florida and subsequent recount. There is more information at a resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page for the 2000 Presidential Election.

The 2000 Presidential election also included the Bush v. Gore Supreme Court case in which the Court stopped a recount of votes in several Florida counties, effectively giving the election to George W. Bush. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a famous dissent in the case.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Research and Report

- Disputed Elections in American Politics describes what happened during the following Presidential elections:

- Election of 2016

- Election of 2000

- Election of 1888

- Election of 1876

- Election of 1824

- Election of 1800

What conclusions do you draw about the Presidential election system based on your findings?

3. ENGAGE: Is It Time to Adopt Instant Runoff/Ranked Choice Voting?

Instant Runoff Voting (IRV)—also called rank-choice voting (RCV)—is a widely discussed idea for reforming American elections.

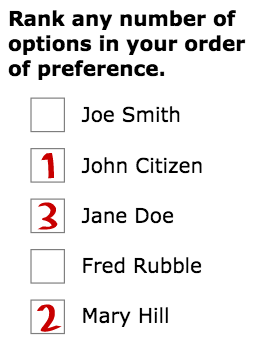

Sample Preferential Ballot for Ranked Choice Voting

"Preferential ballot eo" by Rspeer is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

In instant runoff/ranked choice, voters can vote for more than one candidate by ranking their preferences from first to last. When the votes are counted, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and those votes are redistributed to each voter’s next choice. That process continues till one candidate receives a majority of the votes. Here is an Explanation of Instant Runoff Voting from the Minnesota House of Representatives Research Department.

Maine adopted Rank Choice Voting for primary and federal elections in 2018. After a ruling in 2020 by the state's Supreme Court, Maine will become the first-ever state to use ranked choice voting in a Presidential election. Voters will receive ballots that allow them to rank their preferences between Donald Trump (Republican), Joe Biden (Democrat), Jo Jorgensen (Libertarian), Howard Hawkins (Green) and Rocky De La Fuente (Alliance Party).

Here is how the RCV system works in that state, as explained by the Gorham Maine Committee for Ranked Choice Voting (2016):

"On Election Night, all the ballots are counted for voters’ first choices. If one candidate receives an outright majority, he or she wins. If no candidate receives a majority, the candidate with the fewest first choices is eliminated and voters who liked that candidate the best have their ballots instantly counted for their second choice. This process repeats and last-place candidates lose until one candidate reaches a majority and wins. Your vote counts for your second choice only if your first choice has been eliminated."

IRV and RCV system are now in place for regular and primary elections in cities around the United States, including Berkeley, California, Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the communities Cambridge and Amherst, Massachusetts. In June, 2021, New York City began using IRV in all city primary and special elections, becoming the largest voting population in the country to do so.

IRV is also being used in countries around the world, including Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and the United Kingdom.

Proponents see numerous advantages to ranked-choice system: 1) Voters can support multiple candidates rather than being forced to choose just one who, although perhaps more likely to win, may not most closely align with their values and preferences; 2) Candidates are less likely to engage in personality attacks on opponents since they have an incentive to stress their own credentials in order to appeal to voters, even if they are the second or third choice selections in the poll; 3) Larger political movements can emerge as voters can choose between several progressive or several business-friendly candidates (Ranked-Choice Voting is Already Changing Politics for the Better, The Washington Post, May 4, 2021).

You can learn more about ranked-choice voting and other election reform proposals in Topic 4.5 in this book.

Media Literacy Connections: Political Impacts of Public Opinion Polls

Public Opinion Polls have become an prominent feature of American democracy. A poll is a survey given to a small sample of chosen respondents as a way to reveal what larger numbers of people think about a political issue or election candidate.

Poll results are often widely reported in both print and online media, providing information about people and politics that would not be readily available in other ways. As a matter of media literacy, it is important to understand what polls can and cannot tell us about what people want from government or who people want to elect to public office.

In the following activities, you will gain firsthand experience in conducting and reporting public opinion polls and then you will explore what happens when public opinion polls do not represent the opinion of the public:

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSuggested Learning Activities

- Conduct a Ranked Choice Vote Election in Your School or Classroom

- Set up an election contest such as high school class or middle school class name; students’ favorite candy or ice cream flavor (other than vanilla and chocolate).

- Voters rank the candidates (for example: chocolate chip, buttered pecan, strawberry, cookies and cream) according to their first, second, third and fourth choices.

- Tally the votes and conduct an instant runoff election to determine the winner.

- State Your View

- Did the opportunity to vote for more than one “candidate” heighten interest and involvement in the election process?

- Do you feel that the result was more or less democratic?

Online Resources for Instant Runoff/Ranked Choice Voting

Standard 3.4 Conclusion

In American elections, citizens determine, by voting, who will represent them in the federal, state, and local government. The candidate with the most popular votes is the winner in all elections except for the President. INVESTIGATE explained the Presidential election process and the role of the Electoral College. UNCOVER reviewed disputed elections in U.S. history including the 2000 Presidential election. ENGAGE asked whether it is time to adopt instant runoff/ranked choice voting as an alternative to current practices.