Intervention Overview

Emotional self-regulation includes controlling our reactions, emotions, and desires. In a literature review of various studies regarding the positive effects of emotional self-regulation, Daniel and colleagues (2020) found that emotional regulation promotes wellbeing through the reduction of mental and behavioral disorders, as well as decreased school-related anxiety. Emotional regulation skills are also linked to improvements in resilience and positive emotion. Emotional regulation also serves as a protective mechanism against negative risk factors for the development of mental, emotional and behavioral disorders, such as adverse childhood experiences, trauma, and living in a high stress environment (Daniel et al., 2020).

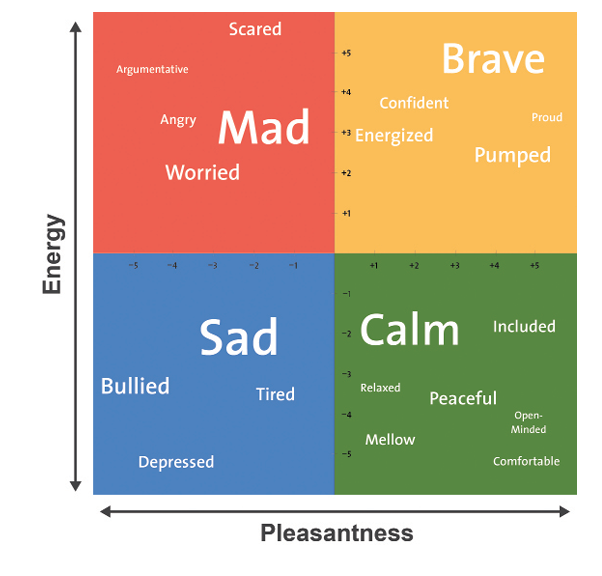

To assist students in self-regulating emotions effectively and learning social and emotional skills, Brackett and Rivers (2014) developed the RULER method. RULER stands for: recognize emotion in self and others, understand an emotion’s cause and potential consequences, label emotions with accurate vocabulary, express emotions in constructive ways, and learn to regulate emotions in positive ways (Nathanson et al., 2016). As part of the RULER method, teachers are encouraged to assist students in recognizing emotions using a mood meter. This helps younger students begin to identify emotions by color zones (red, yellow, green and blue) representing different categories of emotion such as anger, sadness, calm, and happiness (Tominey et al., 2017). An example of the mood meter is included below(Tominey et al., 2017, p. 8).

Though you do not have to use this same mood meter, it is important to establish some common vocabulary regarding emotions with your students. Brackett developed the RULER method into a comprehensive social emotional learning program through the Yale Center of Emotional Intelligence. This program includes the RULER emotional regulation method, mood meter, and additional social emotional learning tools(Nathanson et al., 2016). In order to implement a formal RULER program school-wide, school leaders and educators are encouraged to first participate in a RULER training found here. Though this program is not free, it includes curriculum guides for all grade levels, virtual coaching and training sessions for educators and school leaders, and webinars.

Intervention Guide

|

Grade Level:

|

All

|

|

Materials:

|

Mood meter (or other emotion- identification tools), visual diagram of the RULER method, formal training and curriculum resources for whole-school implementation found here.

|

|

Duration:

|

10 or so minutes daily, or as needed.

|

|

Implementation:

|

- Determine if RULER is the right fit for your school and fits any budget and time constraints.

- Choose a few staff members to participate in the implementation training program.

- Encourage teachers to establish an emotion vocabulary in their classrooms and to assist students in identifying emotions.

- When students experience challenges in the classroom, walk them through the RULER method to help them identify, process and regulate emotions effectively.

|

Does it work?

A randomized-control trial assessing the RULER approach on school climate and student wellbeing was completed across 62 elementary schools, with nearly 4,000 fifth and sixth grade students(Rivers et al., 2013). For this study, participating classrooms were randomly assigned to either use the RULER curriculum during English Language Arts (ELA) classes, or to use the standard ELA curriculum. Teachers participating in the RULER program were given a day and a half long training on the program before implementation. Each of the 12 RULER units on different social and emotional competencies were taught for about two weeks throughout the school year, for about 15-20 minutes daily. Indicators and surveys assessed prior to and following the study showed that classrooms participating in RULER had a more positive classroom climate, greater student participation and student-driven learning, encouraged more cooperative learning, and more positive student-teacher and peer interactions as compared to the control group (Rivers et al., 2013).

A similar smaller study of about 250 fifth and sixth grade students in 15 classrooms assessed the impact of RULER on social and emotional learning, as well as academic performance and motivation (Brackett et al., 2012). The classrooms within the grade level not assigned to the RULER program acted as a comparison group. Students in RULER classrooms were observed over the course of the school year. Following the program, students in the RULER group were shown to have higher academic performance in English Language Arts, stronger work habits and motivation, as well as improved social and emotional skills (Brackett et al., 2012).

References:

Brackett, M. A., & Rivers, S. E. (2014). Transforming students' lives with social and emotional learning. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 368–388). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., Reyes, M. R., & Salovey, P. (2012). Enhancing academic performance and social and emotional competence with the RULER Feeling Words Curriculum. Learning and Individual Differences, 22, 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.10.002

Daniel, S.K., Abdel-Baki, R. & Hall, G.B. (2020). The protective effect of emotion regulation on child and adolescent wellbeing. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 2010–2027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01731-3

Nathanson, L., Rivers, S.E., Flynn, L.M., Brackett, M.A. (2016). Creating emotionally intelligent schools with RULER. Emotion Review, 8(4), 305-310. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1754073916650495

Rivers, S.E., Brackett, M.A., Reyes, M.R., Elbertson, N.A. & Salovey, P. (2013). Improving the social and emotional climate of classrooms: A clustered randomized controlled trial testing the RULER approach. Prevention Science, 14, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0305-2

Tominey, S. L., O’Bryon, E. C., Rivers, S. E., & Shapses, S. (2017). Teaching emotional intelligence in early childhood. YC Young Children, 72(1), 6–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90001479