If I could see you in a year,

I'd wind the months in balls---

And put them each in separate Drawers,

For fear the numbers fuse---

--Emily Dickinson

As self-study researchers, we choose to see ourselves as metaphorically tangled in the threads of time, stories, others’ meaning-making, and our own. Self-study methodology affords us with tools to unstitch and restitch these threads--the complex interplay of processes, methods, and practices--and to make new meanings. Furthermore, we accept our multifaceted responsibility to study teaching practices and self-study research experiences as a way to improve our own teacher education practices and to inform our disciplinary and scholarly fields (Edge & Olan, 2020). In this chapter, upon the loom of composing found poetry, we describe the process of analyzing, interpreting, and representing transformed understandings. In unraveling the tangled mess of participants’ stories threaded through our own narratives, we (re)acknowledged our positionality as narrative inquiry teacher education researchers. As critical friends, we envisioned the act of creating found poetry as an arts-based, literacy research writing, self-study methodology for repositioning ourselves. This methodology creates space to inquire, (re)analyze data, (re)represent it, and transform understanding through meaning-making.

Context

In 2017, we discovered that we each had studied the stories English teachers lived and told, and we each were internally knotted by tensions between knowing the power of these teachers’ stories and the gravity of the responsibility to communicate and to share their stories for the betterment of teaching and learning. Furthermore, at the time of the dissertation, we felt unable to tell our own stories as researchers who made meaning from our participants’ stories. Together, we problematized the situation in order to disrupt the power we felt our untold stories had over us in defining our thinking and doing in our past and present lives (Pahl & Rowsell, 2003). Our feelings about our experiences reminded us of Emily Dickenson’s poem “ If you were coming in the Fall”; we attempted to manage and compartmentalize our participants’ stories from our own, like balls of yarn placed in “separate drawers” for fear of fusing time, space and loss could silence our participants’ experiences and stories by uncovering our own. We recognized the need to free ourselves, to metaphorically unpack the separated, compartmentalized balls of yarn, resist the fear of fusing the then and now, knowing and wondering, being and becoming. Together, we incited ourselves to take action and unthread our experiences in order to revisit our tangled knots of narrative knowing, identity, and experience while making meaning.

As teachers, we turned to writing pedagogy, specifically the act of crafting found poems, we knew had guided our students to create new meaning from existing words. Christi recalled Stephanie Pinnegar reading found poems from S-STEP research papers as a discussant at a 2016 AERA session which encouraged us as researchers. We immersed ourselves in the qualitative and self-study of teaching practices (S-STEP) literature to inform the act of crafting found poems to facilitate our meaning-making, envisionment-building, and enactment of self-inquiry for purposes of informing others.

Existing literature clearly asserts writing is a method for inquiry (Richardson, 2000; Richardson & St Pierre, 2005) and a way of making meaning (Richardson, 1990; Rosenblatt, 2005). Poetic writing has been used as a method for inquiry (Furman, et al., 2006), a tool for qualitative researchers to examine experience (Sjollema, et al., 2012) to create space for creative and imaginative discourse (Patrick, 2016), transform findings from narrative into poetry (Edwards, 2015) and to represent participants’ understandings (Edge, 2011; Prendergast, 2012). Poems found from data have been read aloud to academic audiences (Prendergast, 2012). In self-study methodology, writing poetry has been utilized as a method to explore tensions and potentials of co-learning and co-creativity (Pithouse-Morgan & Samaras, 2019), generate insights for professional learning (Pithouse-Morgan, 2016), and represent understandings from teaching and learning experiences (Hopper & Sanford, 2008). This study builds upon and extends existing literature by documenting how the act of composing found poems from previous, dissertation research is a method of inquiry, analysis, and representation for examining narrative knowledge, identity, and positionality within self-study methodology.

Aims/Objectives

As two teacher-educator researchers who had successfully completed dissertations in narrative inquiry, we felt that materializing teacher-participants’ stories into the world beyond our own minds, was long overdue. We sensed that we needed to re-engage in the dissertation experience in order to convey our teacher-participants’ stories, yet how could we “re-enter” this world of thought from the narrative present?

As critical friends, we began to explore how crafting found poems about deeply constructed understandings might aid us in re-imagining our relationship with our dissertation and our teacher-participants’ stories. We inquired about how we might reposition ourselves to hear the multivoicedness of our temporal, personal-professional, and conceptual (con)texts. We asked ourselves, How, might the act of writing found poems be positioned as both a method for analyzing existing data, and an approach to representing meaning-making from deeply constructed narrative experiences? How might this inquiry process inform our teaching practices for culturally-responsive pedagogy/teaching?

Theoretical Framework

Meaning-Making, Multivoicedness and Meaning in Motion

As teacher educator researchers, we position ourselves as active meaning-makers. We drew from our knowledge of Rosenblatt’s Transactional Theory (Rosenblatt 1978/1994; Rosenblatt, 1994) Langer’s stances when envisioning literature (2011b) and envisioning knowledge (2011a), and Gay’s Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (2010) to guide our sensemaking.

From the Transactional Theory of Reading and Writing (Rosenblatt, 1978/1994), we embrace the epistemological perspective that meaning is made through the dynamic coming together of a particular reader/writer, the text read/composed, in a particular context. We recognize that an individual’s meaning-making is guided by their stance or orientation toward a text, their purpose(s) for reading or writing, and their repertoire of language and experience.

We also embrace a vision of transformative teaching and learning that is informed by Langer’s envisionment building stances for building understanding (Langer, 2011a). An envisionment is “meaning in motion” (p. 17) generated in the act of making meaning, or “the understanding a learner has at any point in time, whether it is growing during reading, being tested against new information, or kept on hold awaiting new input” (pp. 18-19). Meaning-making is potentially ongoing as one learns--confirming, troubling, challenging, and shifting what one knows in light of new meaning-making events. Langer (2011a) asserted, “Stances are crucial to the act of knowledge building because each stance offers a different vantage point from which to gain ideas. The stances are not linear; they can and often do recur at various points in the learning process” (p. 22). The five stances Langer identified include: (1) being out and stepping into an envisionment; (2) being in and moving through an envisionment; (3) stepping out and rethinking what one knows; (4) stepping out and objectifying the experience; and (5) leaving and envisionment and going beyond. Langer posits that the stances are a “useful framework for thinking about instruction” (p. 23). Envisionment building stances are also useful for thinking about a narrative inquirer’s orientation to participants’ stories (Edge, 2011). In this study, we enacted an envisionment building framework as a way to frame and guide our inquiry and meaning-making as we moved from the tightly wound, prior narrative experience represented in the dissertation to the present context of seeking understanding of our narrative lives.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

We came together with the shared appreciation of Geneva Gay’s (2010) work on Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP). Emphasizing teachers’ stances as much as their classroom practices and the social contexts of their lived experiences (Gay 2010; Sleeter, 2012; Villegas & Lucas, 2002), CRP also highlights the value of both student-teacher and student-student interactions. Within interactions, spaces for dialogue emerge (Bakhtin, 1981; Gay 2010, Stewart, 2010). As critical friends, we assumed we could be both learners and researchers, readers and writers whose interactions could generate spaces for dialogue between our individual cultures and the cultures of our past and present research and teaching contexts within the larger context of our narrative lives.

Our theoretical framework and self-study methodology were aligned with contextual knowledge of self, other, social milieu, as well as temporal and cultural professional practice settings, which kept the issue of multivoicedness at the forefront of our data analysis and discussion of results as researchers.

Methods

In this study, we utilized two sets of artifacts--our dissertations as a composite story and our drafts of found poems--as data. Each positioned and repositioned, woven as artifacts, field texts, and representations, situated in and representing three-dimensional narrative spaces of temporality, sociality, and place (Clandinin, et al., 2007; Connelly & Candinin, 2006). First, we framed our completed dissertations (Edge, 2011; Olan, 2012) as artifacts from our narrative pasts to analyze in our narrative present. In other words, we did not look again at the original raw data utilized in the dissertation process; rather, we examined the completed dissertation as story--representing participants’ stories of experience penned through our past narrative inquiries, meaning-making, and individual lived experience as teacher education researchers. Second, our found poem drafts and recorded notes, spoken, and written responses to drafts we crafted from the words in our dissertations became a second artifact.

We met using Skype and Zoom during the 2017-2020 academic years, keeping a Google Document as a running record, and sharing drafts of our found poem writing process, written notes, journal reflections, and interim texts in a shared Google drive.

Data Analysis

Making Found Poems as Inquiry and Analysis. The composition process utilized writing as a method of inquiry (Richardson, 2000; Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005) and a method for knowing and sharing knowing through S-STEP research (Kitchen, 2020). Additionally, composing found poems was a metaphorical double-knitting process for analyzing and representing data; for studying the beginning, middle, and end products and process of inquiry.

Using an interactive process, we independently then collaboratively analyzed our artifacts through composing, interpreting, and responding to found poetry crafted from our dissertations. This process included:

- Noticing and analyzing words to create an untreated poem

- Reading, reacting, and responding to the untreated poem

- Analyzing the untreated poem to compose a treated, found poem

- (Re)Stitching understandings through reading, revising and composing a poem

- Objectifying the experience through interactive discourse with a critical friend

- Identifying (re)envisionments--new visions, insights, observations, and responses as readers, invested and empathetic inquirers, and collaborative meaning-makers

The act of making a found poem from a completed text served as a way to inquire into and analyze our meaning-making when reading, sharing, reacting, interpreting, and composing.

Discourse as Critical Friends. We engaged in dialogic interactions as critical friends (Laboskey, 2004, p. 819) for purposes of being both a “sounding board” (Shuck & Russell, 2005, p. 107) and co-authors who compose new understandings through dialogic interactions (Olan & Edge, 2019). We employed Aveling, Gillespie, and Cornish’s (2015) four principles for “analysing qualitative data informed by multivoicedness” (p. 683). They argue that analysis should include

- Contextual knowledge of self, other, and the social field;

- Openness to alternative interpretations;

- Interpretive skill and contextual knowledge; and

- Reflexivity on the part of the researcher. (p. 683)

Dialogic interactions were further facilitated by the use of a collaborative conference protocol (Bergh et al., 2018) for sharing, active listening, probing, questioning, connecting, and synthesizing meaning-making.

Outcomes: Found Poems as an Approach to Facilitating and Representing Meaning-Making

In this chapter, we describe the process of envisioning new meanings through composing a found poem from a dissertation.

Creating an Untreated Poem

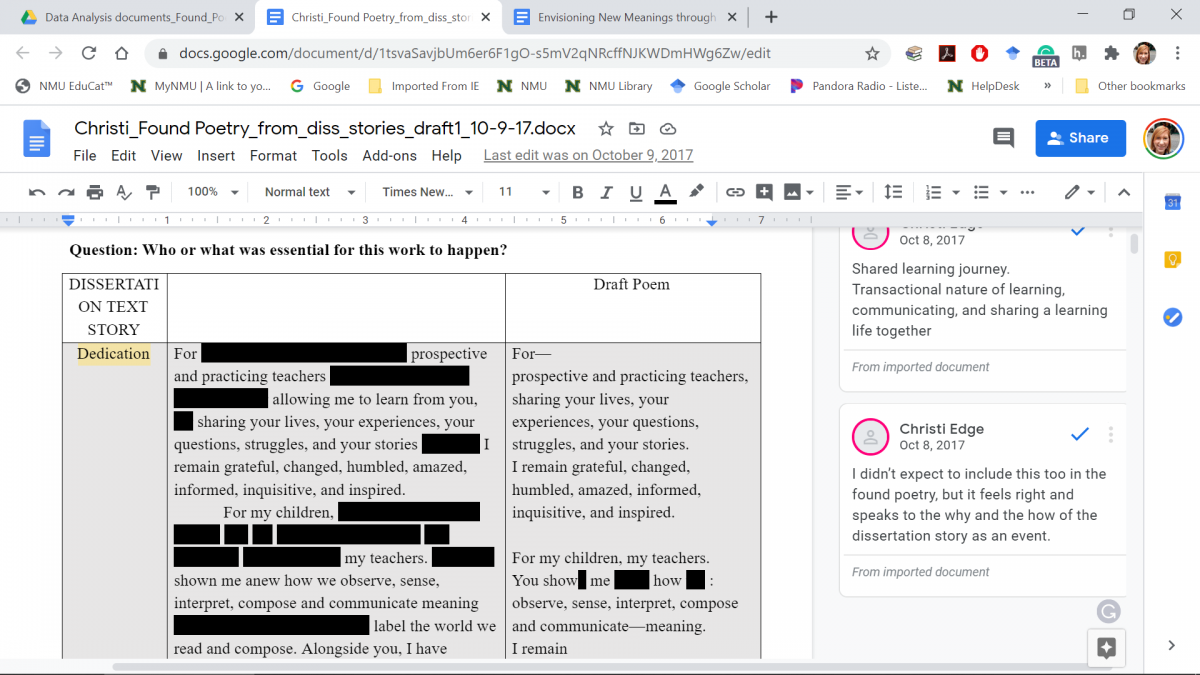

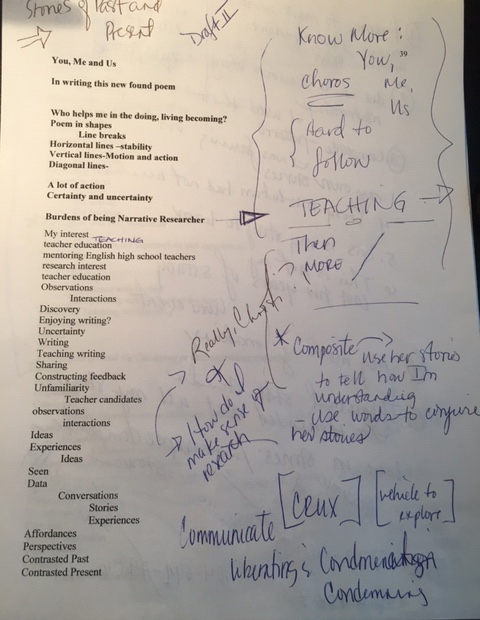

We began our inquiry process by creating an untreated found poem (i.e., one conserving virtually the same order, syntax, and meaning as the original source) (Butler-Kisber, 2010) from our dissertation. We each identified portions (whole chapters, events or stories) that had loose yet, promising ends (see Figure 1) and noted initial inquiry questions.

Figure 1

Noticing and Working with Words. Being outside of and moving into an environment.

The new purpose for writing helped shift our attention from the original dissertation experience to a new experience through identifying and analyzing meaningful words. Christi initially reflected:

How freeing it was to make out words--the found poetry--and re-see and re-imagine the new life in these words, to let the words guide me as I remain open (and distant from the original text) to where the words might lead. (CUE journal, 10/9/2017)

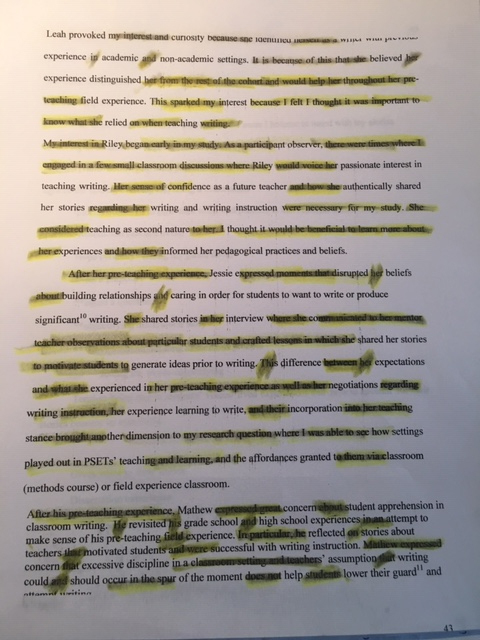

We continued to attend to words, highlighting key verbs, blacking-out the extras (phrases, conjunctions, articles, and other qualifiers) and highlighting or underlining details, words, and phrases that we found powerful, moving, or interesting (See Figure 2). We shared our initial work with one another which prompted additional attention to our meaning making. Which words were we drawn to and why?

Figure 2

Blacking out and Highlighting. Elsie’s (left) and Christi’s (right) noticing words.

Attending to words separated from their original sentences and guided by new questions subtly shifted how we read our original artifacts (dissertations). Christi wrote:

In round two of my working from dissertation text to found poem, my thinking has shifted. I thought I was looking for “found poetry” like I would have my students find and make from their prose. From the story in the introduction of my dissertation, I did just that. BUT, as I became more immersed in re-reading, .... I found myself seeing the poetry that was already there—…. poem in the meaning-making event sense. I began, not marking out text, but highlighting and underlining it. Noticing, where I was making meaning then, and writing comments in margins as I made meaning now, in the present….…In the data I see—really see—how my theoretical framework was guiding my thinking and my reading of [teacher participants’] sense making….I am enacting my theoretical framework beyond what I could fully know in that moment—while observing, or even later (with some heightened sense) while writing and composing the story. Here, I see not only my embodiment of my values, beliefs, and knowledge, but I also see levels of my recognition of this in my written dissertation text (CUE Journal, 10/16/2017)

The act of noticing, separating, and analyzing words--of finding poetry--positioned our stance from being outside the completed past envisionment to moving into a new envisionment in the temporal present. Evocative words prompted meaning-making, creating a transactional event in the present. From the position of the new envisionment-building stance, Christi sees her beliefs, knowledge, and meaning-making voice in her dissertation

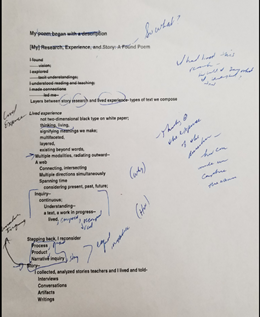

Next, we selected a section to develop into an untreated poem (See Figure 3). On a separate page, we listed highlighted words and phrases, keeping these in the order that we found them. We skipped a line between the words so that they were easy to work with. We looked back over our list and cut out everything that was dull, or unnecessary, or that just didn’t seem right for a poem. We made minor changes necessary to create poems from prose such as adding line breaks, changing punctuation, deletions and minor changes to the words to make them fit together (tenses, possessives, plurals, and capitalizations). Picking up these “threads” of language, we began the act of making a poem--creating, weaving words, untangling memories, stitching present wonderings, in the ever-unfolding loom of meaning-making through composition. Creating an untreated poem, we were in and moving through the envisionment-building stance.

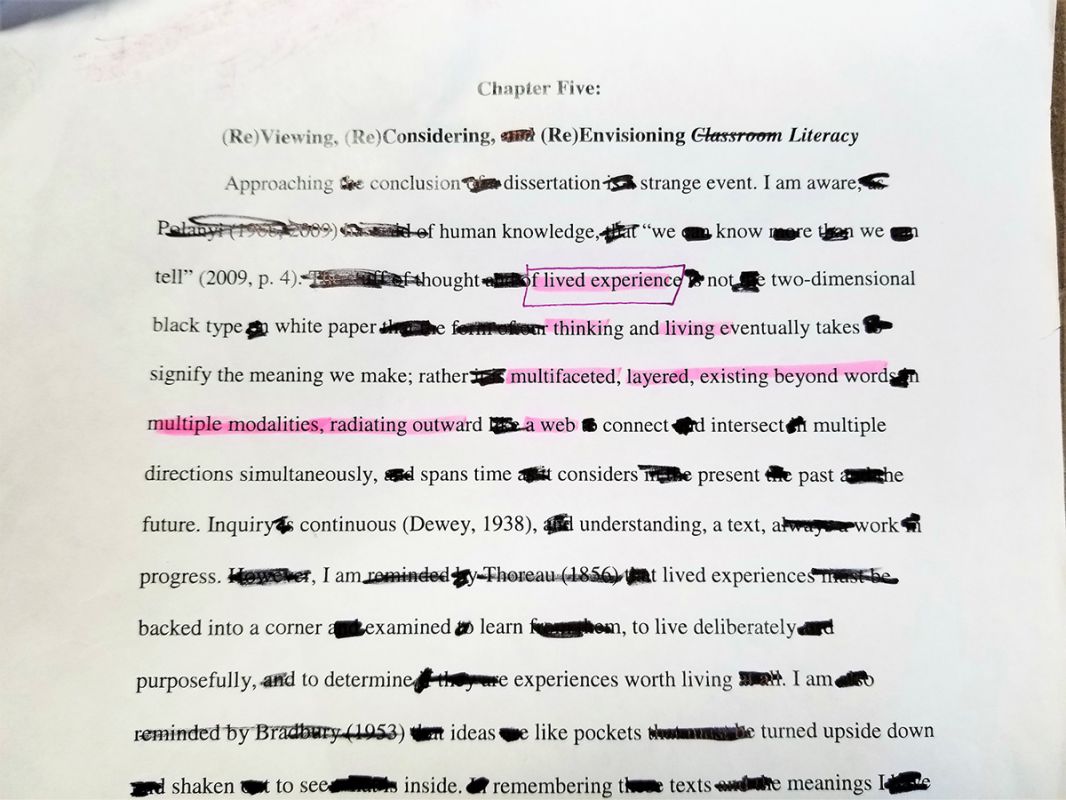

Figure 3

Creating an Untreated Poem. Being in and moving through an envisionment.

Reading, Reacting and Responding to Untreated Poems

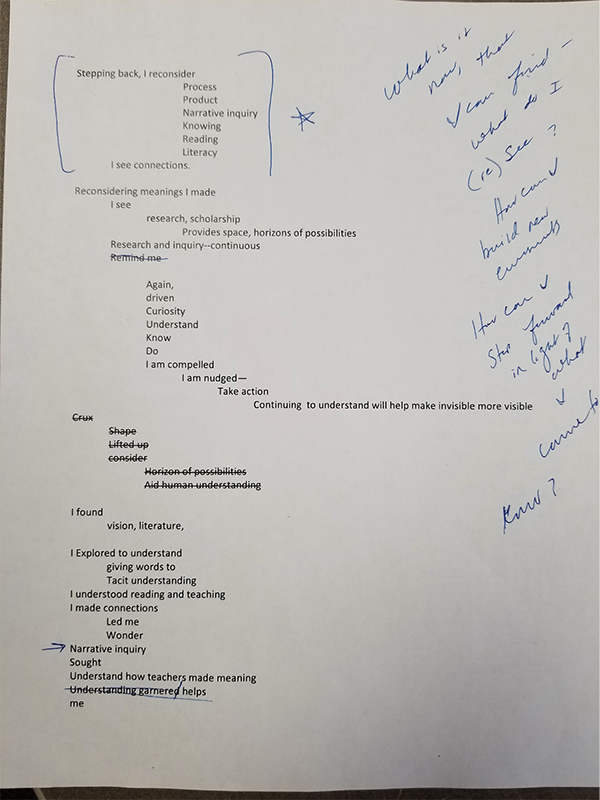

We took turns reading our poem aloud while our critical friend followed along on her own computer screen. After reading the poem, we remained quiet to create space for our critical friend to respond as a listener and as a reader (Bomer & Arens, 2020) by validating, reacting, probing, and inquiring into what was not yet visible to us as the writer. We wrote what we heard one another say and noted our own reactions to critical friend’s comments and questions. For instance, after Christi observed and asked about meaningful repetition, Elsie made connections that later prompted her to restructure her poem around the relationships she formed with participants as they shared their stories. We each stepped back from the moment by distancing ourselves from untreated poem and the initial writing experience to thoughtfully consider our critical friend’s comments and to journal about our new questions prompted by our dialogic interactions (See Figures 4-7).

Figure 4

Reacting and Responding to the Untreated Poem. Stepping back to rethink what one knows and wants to know.

Composing Treated Found Poems

During the new meaning-making event of writing the treated, found poem, we arranged words and ideas in an organic manner; we were creating and crafting, but our actions were driven by a stance of exploration-- of wonderment, praise, and inquiry. In light of the critical friend’s insights, we were able to move the poem--our understanding--forward.

Figure 5

Discourse as Critical Friends: Stepping out of an envisionment to rethink what one knows in an “Aha!” Skype screenshot with Christi (left corner) and Elsie (right front).

Using a collaborative conference protocol provided structure to prompt us to take notes about what one another said, to say what we heard, to offer responses, observations, and questions prompted by the poem and by one another.

Figure 6

Objectifying the Experience through Interactive Discourse with Critical Friend.

In the time and space between poem drafts and meetings, we reconsidered the poem in light of our dialogic interactions. We reconsidered the poem--not the original dissertation text-- as the object of attention and artifact for inquiry. Now focused on our present, we read the text aloud as a participatory event; we engaged in a listening-reading-performing-composing act, arranging the words to communicate the new understandings we had garnered from our dialogic interactions. We also listened for possible line breaks and stanzas, noting where we paused, attending to the silent noise (See Figure 7).

Figure 7

Reconsidering the Poem. Re-entering the envisionment.

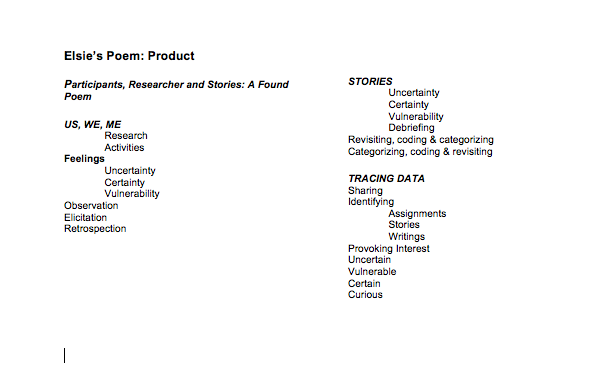

Reinterpreting Narrative Experience through Reading the Found Poem: Making Meaning from New Artifacts

Finally, we typed our new poem. Freed from the bounds of the original text, we generated new understandings, captured in and represented in the artifact of the found poem. We found and made new meaning--a poem (See Figure 8).

Figure 8

Found Poem. New meanings made.

Reading our Found poems enabled us to reinterpret the original experience from the context of the present and to identify new meanings represented in the poem. For example, Elsie identified tensions, values, and emotions:

The phrase Revisiting, coding & categorizing/ Categorizing, coding & revisiting portray how I place value on data gathering, data analysis and methodology, and communicates my struggle with the nonlinear process of revisiting stories that spanned in time. I emphasize the inner feelings that existed in the invisible space between the words and in my inner lifeworld as a researcher. (ELO Interim Text, 3/12/18)

Elsie also identifies relationships and her inner lifeworld:

I used the first person subjective pronoun (we) and the objective pronoun (me/us) to emphasize the relationship between myself, the writer and researcher, and the teachers, who were participants. I speak to feelings evoked as I negotiated the tension between sharing teachers’ stories and disseminating findings that would inform teachers’ and teacher educators’ pedagogical practices. I felt that the moment teachers shared their stories with me, we connected and created a scholarly community cemented on trust, transparency, and loyalty. Their stories were not “just data” to communicate; their stories were artifacts of their lives as teachers; the stories were agents of cultural sensitivity, because they opened their lives and inner lifeworld to me. In this process, the me became us.

Found poem artifacts also enabled us to identify and communicate positionality and shifts in understanding. For example, Elsie wrote:

This [last] stanza reflects the iterative process of narrative inquiry; uncertainty shifts to uncertain. I am agentitive owner of my positionality. During this iterative process, it is my hope that my work will inform the field while being true to teacher participants’ stories. The poem ends in a way that the next experience will begin. In the refrain uncertainty, certainty and vulnerability, and then the break from that pattern, I seek to disclose a new way of re-seeing my dissertation study and looking to my data to incite new insights. (ELO Interim Text, 3/12/18)

Furthering the Conversation

As a result of our inquiry, (1) we recognize composing the found poem became a conduit for meaning-making that supported the transactional reading-writing relationship (Rosenblatt, 1978/1994; Rosenblatt, 2005) between the reader/writer/researcher and research texts. In finding and making poems, we were immersed in the envisionment-building, dialogic, tension-filled spaces where meaning is made. Like being braided, meaning is twisted and woven into the spaces of intertextuality, dialogism, and transacting with texts that are written, spoken, thought, and felt--these weavings are paradoxically simple, complex, and rigorous; lived, studied, and told; read, discussed, and composed; inquiry, analysis, and representation. Furthermore, (2) dialogue with a critical friend invited tensions to disrupt and problematize our thinking through new observations, connections, and insights, and (3) discovering poetry within the lines of prose helped us to untangle and trace the threads of past and present understanding for purposes of present and anticipated future professional practices. Finally, (4) writing found poetry became a way to see and study our lived experiences.

Discourse and Tension in Critical Friendship Facilitates Unstitching and (Re)Stitching Narrative Understanding

As critical friends, we discovered that by revisiting, repositioning and rethinking through co-authoring and dialogic processes, we were able to revisit, reignite, disrupt, problematize and challenge one’s past and present storied lives (Olan & Edge, 2019) In this process, we disrupted existing fears and prior conceptions of our lived experiences. We made a conscientious effort to untangle through our roles as critical friends, to probe and make space to evoke inquiry and welcome the discomfort associated with the asking of provocative intimate scholarship questions.

Found Poems as Analysis and Representation of Meaning Making in Motion

As threads in a tapestry intertwine and intricately honor the uniqueness of each thread, our critical friendship recognized our individual meaning-making while welcoming our different vantage points, experiences and narrative discourses. We navigated the difficulty of constructing research while being a “keeper” of our participants’ stories. We acknowledged and disclosed our feelings of uneasiness with possessing and disclosing our participants’ stories and our attempt to re-enter the past meanings to better connect to our present. We spoke about our vulnerabilities and tensions and feelings of loss that lingered beyond our dissertation process. We “pushed” each other to look inward as teachers and teacher educator-researchers and think about our pedagogical practices, values, and beliefs, and how these practices may facilitate our narrative discourse and writing found poetry as meaning-making.

Regenerating new ideas liberated us to “step into” the envisionment-building space of the dissertation and then “step back” with new insights that connected the narrative past (former experiences and understandings) with the narrative present (current roles, knowledge and experiences). The ability to move between the “worlds” of understanding was liberating. The artifact filled with memory, identity, emotion, relationships, embodied knowledge, and transformation had been relinquished out into the world through the vulnerable-safe space of dialogue with a critical friend. After Elsie completed her treated poem, she reflected on how her meaning-making lent understanding of her students’ learning:

The more I look at this poem, the more I’m intrigued--not only about the found poem but about the power of writing a dissertation had, my pedagogical stance. I now have a better sense of how I felt during my dissertation experience...I could re-engage and … be immersed. My found poem represents not only the disparity but also the juxtaposition of writing research that talks about pedagogical practices and my participants’ journey, their teaching and their learning with…. I couldn’t use my practices in my dissertation research… I went into the experience with 17 years…yet that was never enough. I couldn’t rely on that experience and use it to help me succeed. I had to relearn how to approach texts (theoretical frame….etc.)

I understand how my students grapple with the courses that they are taking. I too struggled. Look at all the knowledge and experience I had to frontload and scaffold my success, yet I needed more. I needed a way to navigate continuously juggling what I’m reading with what I’ve lived, and about now. Crafting the found poem, I was able to re-engage in the dissertation writing experience and re-enter my participants’ stories… I found new meaning, new dimension to that dissertation chapter (that I already loved), but could see now in a new light, see from multiple angles. I was so attached to it, that I couldn’t see beyond; found poetry helped us both to see new possibilities.

Engaging in the writing process, we talked about what we were feeling, we contextualized it, stepped back, and realized it means a bit more. As a result, we are better attuned to the cultures we are immersed in. The dissertation and found poem as artifacts provided platforms for us to revisit our preconceived notions, step back, resituate ourselves in our new surroundings and step out while recognizing our surroundings. Found poetry enables individuals to evoke the fourth and fifth envisionment-building stances, enabling them to “step back” and reconsider what they know, and to potentially develop deeper understandings that disrupt and/or transform understanding.

By using a strategy that we had previously implemented in our classrooms- writing found poems, we were able to reposition ourselves to hear the multivoicedness of our contexts. Just like our students, we acquired a sense of awareness regarding our writing’s context, audience, purpose, and impact. We too had stopped and stared at the multiple pages that told our teacher participants’ stories and could not move forward. The words seemed to form an entity of their own, occupying a space that constricted our breathing. We felt we had very little to reveal from those stories. Nevertheless, as we engaged in finding a poem from our existing prose, we re-entered the existing text with a new purpose. Blacking out some words highlighted others and revealed insights in the newly made whitespace upon the page. Found poems enabled dimensionality through “poetic language that is saturated with possibilities of meaning (Brochner, 2005, p.299). Poetic language lent prismatic perspectives for us to converse through with critical friends.

Through dialogic interaction, we further disrupted one another’s previous writing paralysis (Zinzer, 2001 p. 77) by offering new insights, observations, and responses as readers, invested and empathetic inquirers, and collaborative meaning-makers. Recomposing the poem after engaging in dialogic interactions created space to re-see and reimagine the untreated poem into a new, treated poem that could be read and interpreted as an artifact of our present (and anticipated future) perspectives, identities, and roles.

New Envisionments

Through the dynamic interplay of transactional meaning-making, we positioned and repositioned ourselves as critical friends who co-author meaning (Olan & Edge, 2019) through invited tension as a method for (re)knowing. We utilized a process of found poetry writing as a method for self-study in order to inquire into, analyze, and represent meaning-making. Like threads upon a loom, the process of coming to know is made through and represented by the constant and ongoing interconnecting-- of artifacts, dialogism, action, discourse as collaborative, critical friends (Hamilton & Pinnegar, 2015), and envisionment building for purposes of (re)generating knowledge, for making, new, meanings. Attuning to the threads of narrative knowing, identity, and becoming, we lean back to observe the ever-unfolding, unstitching, restitching, being open to possibilities amidst and against the external tension of the metaphorical loom as well as the internal tension between the artist’s initial and unfolding visions. Through self-study with a critical friend, the poem as meaning-making event (Rosenblatt, 1978/1994) unfolds before us, weaving new threads, in the space of new tensions, resulting in new understandings. Analyzing and representing data through the process of composing found poems with a critical friend generates the vulnerable-confident, self-other; vision-revision; reading-composing; critiquing-discovering; powerful-empowering; learning-teaching; textual-intertextual; three-dimensional spaces for ongoing transformation upon the loom of self-study methodology.

References

Aveling, E. L. Gillespie, A. & Cornish, F. (2015). A qualitative method for analysing multivoicedness. Qualitative Research, 15(6), 670-687.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination. University of Austin Press.

Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (Eds.). (2019). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives. Wiley & Sons

Bergh, B., Edge, C., & Cameron-Standerford, A. (2018). Reframing our use of visual literacy through academic diversity: A cross-disciplinary collaborative self-study. In J. Sharkey & M.M. Peercy (Eds.), Self-study of language and literacy teacher education practices across culturally and linguistically diverse contexts (pp. 115–142). Emerald Group Publishing.

Bomer, K., & Arens, C. (2020). A teacher’s guide to writing workshop essentials: Time, choice, response. Heinemann.

Butler-Kisber, L. (2010). Qualitative inquiry: Thematic, narrative and arts-informed perspectives. Sage.

Clandinin, D. J., Pushor, D., & Orr, A. M. (2007). Navigating sites for narrative inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(1), 21-35.

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative Inquiry. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, P. B. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 477-487). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Collecting qualitative data. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 204-235). Pearson.

Dickenson. E. (1890). If you were coming in the fall. Emily Dickinson Archive. https://edtechbooks.org/-rmW

Edge, C. (2011). Making meaning with ‘readers’ and ‘texts’: A narrative inquiry into two beginning English teachers’ meaning-making from classroom events. Graduate School Theses and Dissertations. https://edtechbooks.org/-CtBa

Edwards, S. L. (2015). Transforming the findings of narrative research into poetry. Nurse Researcher, 22(5), 35-39.

Edge, C., & Olan, E. L. (2020). Reading, literacy, and English language arts teacher education: Making meaning from self-studies of teacher education practices. In J. Kitchen, A. Berry, S. Bullock, A. Crowe, H. Guðjónsdóttir, J. Kitchen, & M. Taylor (Eds.). 2nd International handbook for self-study of teaching and teacher education (pp. 1-43). Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-1710-1_27-1

Eliot, T. S. (1942). T. S. Eliot’s Little Gidding. Retrieved March 15, 2018 from https://edtechbooks.org/-LLc

Furman, R. Lietz, C., & Langer, C. (2006). The research poem in international social work: Innovations in qualitative methodology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5(3), 24-34.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd.ed.). Teachers College Press.

Hamilton, M. L., Pinnegar, S., & Journey, P. A. D. (2015). Knowing, becoming, doing as teacher educators: Identity, intimate scholarship, inquiry. Emerald Group Publishing.

Hopper, T., & Sanford, K. (2008). Using poetic representation to support the development of teachers’ knowledge. Studying Teacher Education, 4(1) 29-45. https://edtechbooks.org/-ybVD

Kitchen, J. (2020). Envisioning writing as a way of knowing in self-study. In C. Edge, A. Cameron-Standerford, & B. Bergh (Eds.), Textiles and tapestries. EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-qVt

LaBoskey, V. K. (2004). The methodology of self-study and its theoretical underpinnings. In J. J. Loughran, M. L. Hamilton, V. K. LaBoskey, & T. Russell (Eds.), International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices (pp. 817-869). Springer.

Langer, J.A. (2011a). Envisioning knowledge: Building literacy in the academic disciplines. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Langer, J. (2011b). Envisioning literature: Literary understanding and literature instruction. Teachers College Press.

Olan, E. L. (2012). Stories of the past and present: What preservice secondary teachers draw on when learning to teach writing. Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University.

Olan, E. L., & Edge, C. (2019). Collaborative meaning-making and dialogic interactions in critical friends as co-authors. Studying Teacher Education, 15(1), 31-43. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2019.1580011

Pahl, K., & Roswell, J. (2003). Artifactual literacies. In J. Larson & J. Marsh (Eds.), The Sage handbook of early childhood literacy (pp. 263-278) Sage.

Patrick, L. D. (2016). Found poetry: Creating space for imaginative arts-based literacy research writing. Literacy Research: Theory, Method, and Practice, 65, 384-03. https://edtechbooks.org/-PGt.

Pithouse-Morgan, K. (2016). Finding my self in a new place: Exploring professional learning through found poetry. Teacher Learning and Professional Development, 1(1), 1-8. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-bxn.

Pithouse-Morgan, K. & Samaras, A. P. (2019). Polyvocal play: A poetic bricolage of the why of our transdisciplinary self-study research. Studying Teacher Education, 15(1), 4-18. https://edtechbooks.org/-Xqt

Prendergast, M. (2012). Education and/as art: A found poetry suite. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 13(2). Retrieved from http://www.ijea.org/v13i2/.

Richardson, L. (2000). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 512-529). Sage.

Richardson, L. (1990). Writing strategies: Reaching diverse audiences. Sage.

Richardson, L. & St. Pierre, E. A. (2005). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed.) (pp. 959-978). Sage.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (2005). Making meaning with texts: Selected essays. Heinemann.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1978/1994). The reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. SIU Press.

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In R. R. Ruddell, M. R. Ruddell, & H. Singer (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (4th ed.) (pp. 1057-1092). International Reading Association.

Schuck, S., & Russell, T. (2005). Self-study, critical friendship, and the complexities of teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 1(2), 107–121.

Sjollema, S. D., Hordyk, S., Walsh, C. A., Hanley, J., & Ives, N. (2012). Found poetry - Finding home: A qualitative study of homeless immigrant women. Journal of Poetry Therapy, 25(4), 205-217. https://edtechbooks.org/-IdGb

Sleeter, C. E. (2012). Confronting the marginalization of culturally responsive pedagogy. Urban Education, 47(3), 562-584.

Stewart, T. T. (2010). A dialogic pedagogy: Looking to Mikhail Bakhtin for alternatives to standards period teaching practices. Critical Education, 1(6), 1-20.

Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20-32.

Zinsser, W. (2001). On writing well: The classic guide to writing nonfiction. Quill.