Standard 7.5: Evaluating Print and Online Media

Explain methods for evaluating information and opinion in print and online media. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T7.5]

The fin de siècle newspaper proprietor, by Frederick Burr Opper, Library of Congress {{PD-art-US}}

The fin de siècle newspaper proprietor, by Frederick Burr Opper, Library of Congress {{PD-art-US}}FOCUS QUESTION: What is Fake News and Information Disorder and How Can Students Become Critical Consumers of Print and Online Information?

What type of news consumer are you? Do you?

- Check headlines several times a day or only once in a while?

- Read a print newspaper or online news articles every day or only occasionally?

- Watch the news on television or stream it online or mostly avoid those sources of information?

- Subscribe to online newsletters that provide summaries of the latest news (e.g., theSkimm)?

- Critically assess the information you receive to determine its accuracy and truthfulness?

Many commentators, including many journalists, assume most people are not active news consumers. They believe that a large majority of the public rarely go beyond the headlines to read in-depth about a topic or issue in the news.

Yet when surveyed, nearly two-thirds (63%) of Americans say they actively seek out the news several times a day. They report watching, reading, and listening to the news at about equal rates (American Press Institute’s Media Insight Project).

At the same time, however, far fewer people regularly seek out commentary and analysis about the news (Americans and the News Media: What They Do--and Don't--Understand about Each Other, American Press Institute, June 11, 2018).

Whatever type of news consumer you are, making sense of online and print information is a complex endeavor. It is easy to get lost in the swirl of news, opinion, commentary, and outright deception that comes forth 24/7 to computers, smartphones, televisions, and radios.

Fake and False News

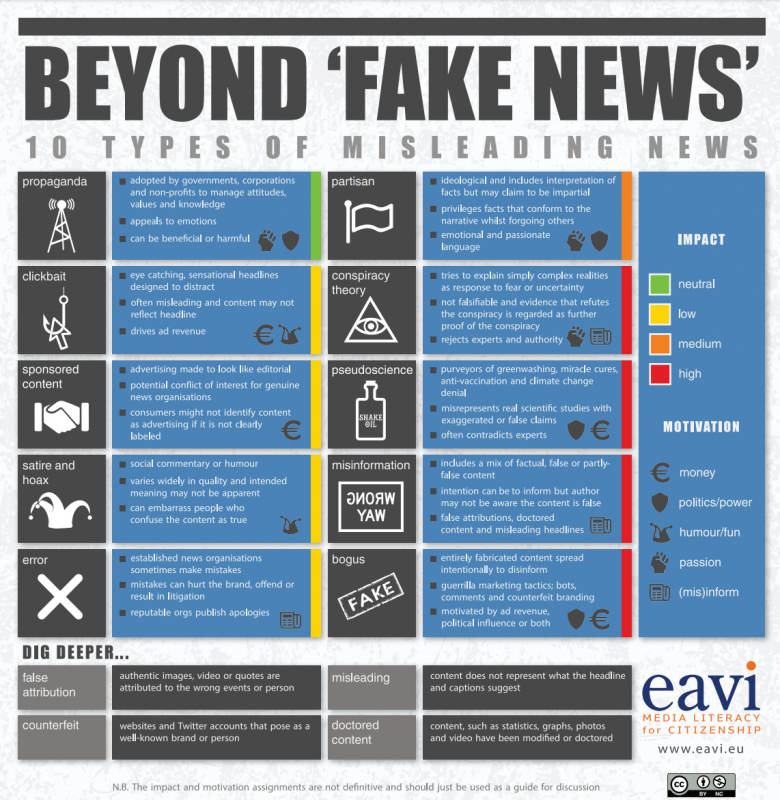

The growth of instant news and widely shared misinformation (fake and false news) has become one of the dominant media developments of the past 20 years (How Technology and the World Has Changed Since 9/11, Brookings, August 27, 2021). Fake and false news, defined as “information that is clearly and demonstrably fabricated and that has been packaged and distributed to appear as legitimate news" (Media Matters, February 13, 2017, para. 1) as well as misleading news (see "Beyond Fake News" infographic below).

Infographic: Beyond Fake News | CC BY-NC 4.0

Infographic: Beyond Fake News | CC BY-NC 4.0Information researchers Whitney Phillips and Ryan M. Milner (2020) characterized three dominant types of fake and false news in their book You Are Here: A Field Guide for Navigating Polarized Speech, Conspiracy Theories, and Our Polluted Media Landscape:

- Disinformation is false information deliberately spread.

- Misinformation is false information inadvertently spread.

- Malinformation is false information deliberately spread to cause harm.

NPR journalist Alex Clark (2021) defines “misinformation” as a “blanket term for inaccurate communication” that serves to take listeners, readers, and viewers “further away from what’s actually going on in the world” (para. 6-7) When misinformation is used for political purposes and partisan gain, it becomes “disinformation.” Both forms of distorted communication can shape people’s views of the world, leading us to believe untruths and lies. Check out Why Misinformation Matters from PBS to learn more.

Fake and false news is a central part of a wider problem of Information Disorder, a condition that results when "bad information becomes as prevalent, persuasive, and persistent as good information" (Aspen Institute, 2021, p. 1). Facing a society beset with information disorder, argues the Aspen Institute (2021), people lose the capacity to understand their lives and make reasonable and informed choices about the future. They live every day in a "world disordered by lies" (p. 1).

The activities in this topic are designed to help teachers and students develop the tools and strategies they need to critically evaluate what is being said and by whom in today's multifaceted news and information landscape. A companion Critical Media Literary activity offers strategies for doing visual analyses of online and print media.

1. INVESTIGATE: Defining “Fake News” and Finding Reliable Information

Fake news comes from many sources. Political groups seek to gain votes and support by posting information favorable to their point of view— truthful or not. Governments push forth fake news about their plans and policies while labeling those who challenge them as inaccurately spreading rumors and untruths. In addition, unscrupulous individuals make money posting fake news. Explosive, hyperbolic stories generate lots of attention and each click on a site generates exposure for advertisers and revenue for fake news creators (see NPR article: We Tracked Down A Fake-News Creator In The Suburbs. Here's What We Learned).

People’s willingness to believe fake news is encouraged by what historian Richard Hofstadter (1965) called “the paranoid style in American politics.” Writing in the 1950s and 1960s, Hofstadter’s analysis still applies to today’s world of hyper-charged social media and television programming.

In Hofstadter’s view, people throughout American history have tended to respond strongly to the “great drama of the public scene” (1965, p. xxxiv). In times of change, people begin thinking they are living “in the grip of a vast conspiracy” and in response, they adopt a paranoid style with its “qualities of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” (Hofstadter, 1965, pp. xxxv, 3). Caught within a paranoid style, people see conspiracies against them and their views.

Fake news distributed on social media feeds conspiracy theories while promoting the agendas of marginal political groups seeking influence within the wider society. In summer 2020, during a nationwide spike in COVID-19 cases, a video created by the right wing news organization Breitbart claiming that masks were unnecessary and the drug Hydroxychloroquine cured the virus was viewed by 14 million people in six hours on Facebook. At the same time, the Sinclair Broadcast Group, another right-wing media organization that reaches 40% of all Americans, published an online interview with a discredited scientist who claimed Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, created the coronavirus using monkey cells (Leonhardt, 2020).

Special Topic Box: A Brief History of Fake News in American Politics

Distorting information and distributing fake news has long been part of American politics, from colonial times to the current pandemic era..

- In 1782, Benjamin Franklin wrote a hoax supplement to a Boston newspaper charging that Native Americans, working in partnership with England, were committing horrible acts of violence against colonists (Benjamin Franklin's Supplement to the Boston Independent Chronicle, 1782, from the National Archives).

- In 1835, the New York Sun newspaper created the Great Moon Hoax, convincing readers that astronomers had located an advanced civilization living on the moon (The Great Moon Hoax, 1835).

Portrait of a Man Bat from the Great Moon Hoax, by Lock (?) Naples, {{PD-art-US}}

Portrait of a Man Bat from the Great Moon Hoax, by Lock (?) Naples, {{PD-art-US}}- The rise of Yellow Journalism in the 1890s as part of the competition between newspapers owned by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst played a significant part in the nation’s entry into the Spanish-American War (for more, go to the UNCOVER section of the standard).

- During the Vietnam War, overly favorable reports of military success that the U. S. military presented to reporters have since become known as the The Five O'Clock Follies (Hallin, 1986).

As a candidate and President, in speeches and tweets, Donald Trump promoted numerous conspiracy theories, including, but not limited to:

- Barack Obama was not born in the United States.

- Millions voted illegally and against him in the 2016 and 2020 elections.

- Vaccines cause autism or produce other harmful effects.

- Wind farms cause cancer.

- Climate change and global warming is a hoax created by the Chinese government (Associated Press, 2019).

- During the height of the COVID pandemic, in September 2020, Twitter said it had over one million posts with inaccurate, unreliable, or false pandemic information; Facebook and Instagram reported they had removed over 20 million COVID-19 misinformation posts by August 2021 (UNESCO, 2021).

Link here to more about the history of fake news:

The Disinformation Dozen

A small number of fake news creators can have an enormous impact on public attitudes and behaviors. As COVID variants surged among unvaccinated Americans during the summer of 2021, researchers found that 65% of shares of anti-vaccine misinformation on social media came from just 12 people (the so-called "Disinformation Dozen"), running multiple accounts across several online platforms (NPR, May 14, 2021). For some of these individuals, providing misinformation directed at the 20% of people who do not want to be vaccinated is a highly profitable business model (NPR, May 12, 2021). You can learn more about how fake news spreads online at NPR's special series Untangling Disinformation.

Promoting fake news can be highly profitable for politicians who use misinformation to entice people to donate money to their campaigns. In an ongoing investigation, The New York Times (April 17, 2021) has documented how former President Donald Trump and the Republican Party have used the Big Lie that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen to raise millions of dollars from donors, many of whom made small monetary contributions who believed lies about the election and efforts to overturn it. The Trump campaign received more than 2 million donations between the election in November and the end of 2020. Since then, Save America, a Trump political action committee has raised millions through online advertising, text-message outreach and television ads.

The Demise of the Fairness Doctrine

The demise of the fairness doctrine in 1987 has had an immense impact on the expansion of fake and false news in the media. The fairness doctrine was a rule developed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that required television and radio stations licensed by the FCC to "(a) devote some of their programming to controversial issues of public importance and (b) allow the airing of opposing views on those issues" (Everything You Need to Know About the Fairness Doctrine in One Post, The Washington Post, August 23, 2011). It was adopted in 1949 as an expansion of the Radio Act of 1927 that required broadcast licenses could only be given to those who serve the public interest.

The Fairness Doctrine meant broadcasters had an "active duty" to cover issues that matter to the public (not just political campaigns, but local, state, regional and national topics of importance) in a "fair manner" Fairness Doctrine: History and Constitutional Issues, Congressional Research Service, July 13, 2011). Programming could not be one-sided, anyone attacked or criticized had to given the opportunity to respond, and if the broadcasters endorsed a candidate, other candidates had to be invited to present their views as well.

The ending of the Fairness Doctrine coincided with the rise of conservative talk radio. Unrestrained by norms calling for reasonably fair coverage of issues, political talk show hosts, notably Rush Limbaugh, rose to prominence using hate-filled inflammatory language and outright misinformation to attract millions of listeners. Conservative talk radio generated an echo chamber for right-wing political views, many of which were wholeheartedly adopted by Republican Party candidates.

You can learn more by listening to How Conservative Talk Radio Transformed American Politics, a podcast from Texas Public Radio and reading Talk Radio's America: How an Industry Took Over a Political Party That Took Over the United States by Brian Rosenwald (2019).

Finding Sources of Reliable Information

Readers and viewers must develop critical reading, critical viewing, and fact- and bias-checking skills to separate false from credible and reliable information in print and online media. ISTE has identified Top 10 Sites to Help Students Check Their Facts.

The University of Oregon Libraries recommend teachers and students employ the strategy of S.I.F.T. when evaluating information they find online or in print:

- STOP and begin ask questions about what you are reading and viewing.

- INVESTIGATE the source of the information; who wrote and what is their point of view.

- FIND trusted coverage of the topic as a way to compare and contrast what you learning.

- TRACE the claims being made back to their original sources.

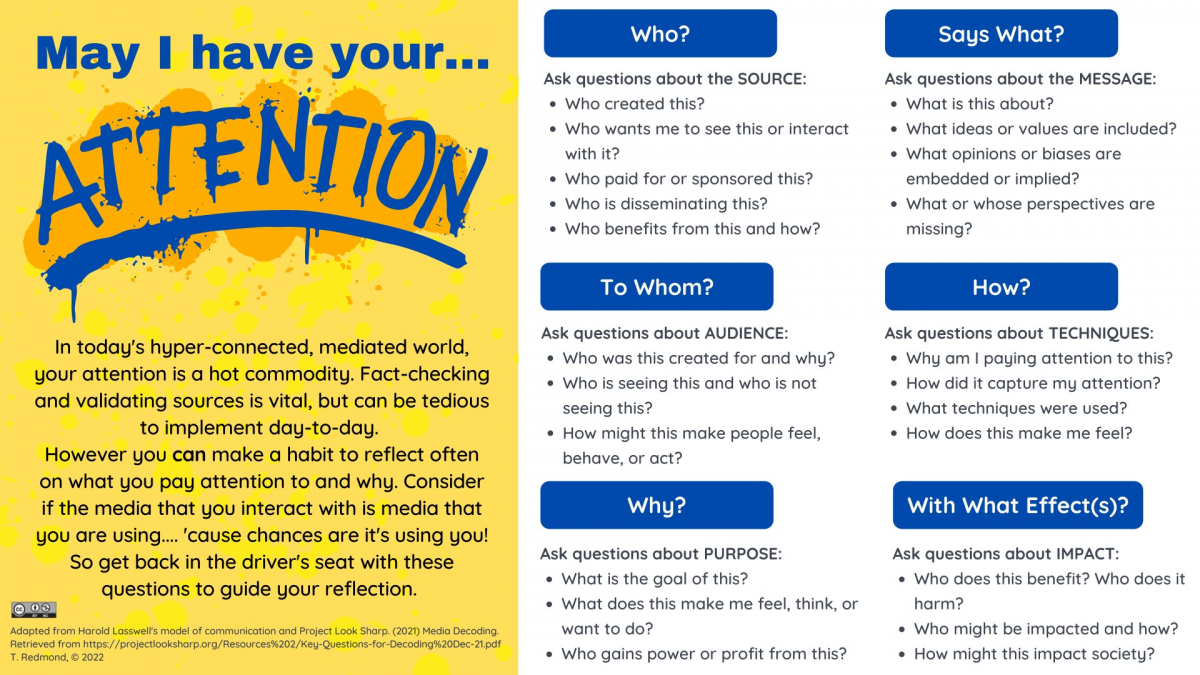

What questions should you ask? Check out Theresa Redmond's "May I have your...Attention" graphic, which features questions adapted from Harold Lasswell's Model of Communication and Project Look Sharp (2021) Categories and Sample Questions for Media Decoding.

"May I have your...Attention" by Theresa Redmond is licensed under CC BY NC

"May I have your...Attention" by Theresa Redmond is licensed under CC BY NCIn addition to utilizing critical reading, viewing, and fact- and bias-checking skills, it is important to develop one's own sources of trusted and reliable information from fact-based journalists and news organizations. To gain an overview of the challenges facing students and teachers, listen and read the following text-to-speech version of Fighting Fake News from The New York Times UpFront (September 4, 2017).

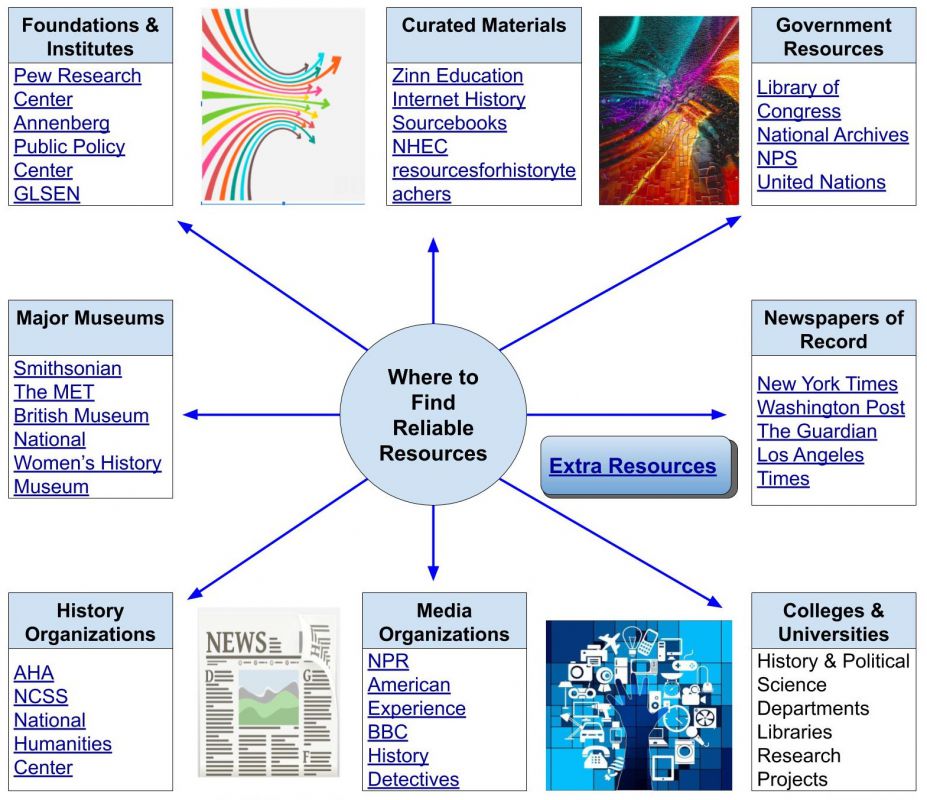

Here is an infographic developed to guide teachers and students in locating reliable online resources.

Where to Find Reliable Resources Infographic by Robert W. Maloy, Torrey Trust, & Chenyang Xu, College of Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0

Where to Find Reliable Resources Infographic by Robert W. Maloy, Torrey Trust, & Chenyang Xu, College of Education, University of Massachusetts Amherst is licensed under CC BY NC SA 4.0Where To Find Reliable Resources Infographic (make your own copy to remix)

Media Literacy Connections: Critical Visual Analysis of Online and Print Media

Seeing is believing, except when what you see is not actually true. Many people tend to accept without question the images they see in advertising, websites, films, television, and other media. Such an uncritical stance toward visual content can leave one open to distortion, misinformation, and uninformed decision-making based on fake and false information.

Learning how to conduct a critical visual analysis is critical for living in a media-filled society. By engaging in critical visual analysis of the media, you can make more informed decisions regarding your civic, political, and private life.

As a first step in evaluating visual sources, the history education organization, Facing History and Ourselves, suggests the critical viewing approach of See, Think, Wonder. The goal is to evaluate images by asking questions about them before drawing conclusions as to meaning and accuracy.

The following critical visual analysis activities expand the See, Think, Wonder approach by offering opportunities to evaluate different types of visuals for their trustworthiness as information sources.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSuggested Learning Activities

- Curate a Collection:

- Find examples of the 6 types of fake news identified by researchers in the journal Digital Journalism in 2017 (Defining Fake News):

- Satire - Commenting on actual topics and people in the news in a humorous, fun-filled manner. For more about satire, visit Why Satirical News Sites Matter for Society.

- Parody - Pretending to be actual news, delivered in a joking manner without the intention to deceive, even though some of the material may be untrue.

- Propaganda - Purposefully misleading information designed to influence people’s viewpoints and actions.

- Photo and video manipulation (also known as “deepfakes”) - Manipulating pictures and videos to create images and sounds that appear real, but are not.

- Advertising - Providing positive and favorable information to convince people to purchase a product or service.

Fabrication - Deliberately providing fake and false information about a topic.

- Discuss and State Your View

- In what ways does satire and parody differ from fabrication and manipulation?

- In what ways does propaganda differ from advertising?

- What is the purpose of each type of fake news?

- Which of these 6 types of fake news do you think is shared the most on social media?

- Evaluate and Assess:

- Explore the Interactive Media Bias Chart which rates news providers on a grid featuring a political spectrum from left to right as well as the degrees to which news providers report news; offer fair or unfair interpretations of the news; and present nonsense information damaging to the public discourse.

- Do you agree with the findings of the Media Bias Chart?

- Write a Social Media Post

- Have students create two social media posts about (one real, one fake) about an issue of their choosing.

- Share the posts with the class.

- Have students rate each post on how believable it is.

- Discuss with students:

- What criteria did you use to determine whether a news story was fake or real?

- What features of the stories influenced believability (e.g., well-written, quality visuals)?

Teacher-Designed Learning Plan: Is it Real or Fake News?

Use this list (or this table) to evaluate the reliability of a news story you read online:

- What author wrote and what organization published the article?

- What do you know about the author or the organization?

- What seems to be the purpose of the article?

- Does the article give different sides of the issue or topic? Or does it seem biased (Does it try to appeal to confirmation bias?)? Explain.

- If the article has a shocking headline, does it have facts and quotes to back it up? (Note: Some fake news sources count on people reading only the headline of a story before sharing it on social media!) Please list a few examples.

- Can you verify the story in a news source you know you can trust— like the website of a well-known newspaper, magazine, or TV news program?

- Please use another site to check the credibility of your article?

- What site did you choose? WHY?

NOTE: Teachers can assign specific articles both real and fake for students to examine. Be careful, sometimes the URLs give them away.

Resources to reference:

Alternatively, students could review the information literacy frameworks below and then generate their own rubric for evaluating different type of sources (e.g., news, images, videos, podcasts):

Online Resources for Detecting Fake and False News

- Learning Activities

- Additional Reading

- Video

2. UNCOVER: Yellow Journalism and the Spanish American War

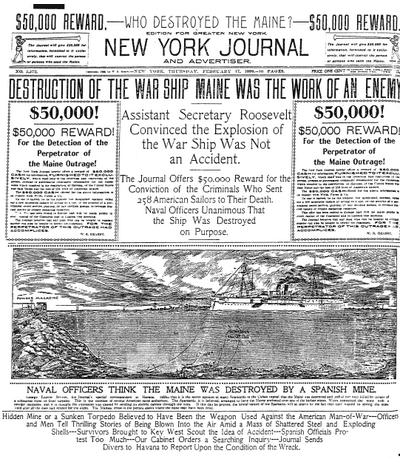

A famous historical example of fake news was the role of Yellow Journalism at the outset of the Spanish American War. On February 16, 1898, the United States battleship Maine exploded and sank in Havana Harbor in Cuba—268 sailors died, two-thirds of the ship’s crew (Maine, a United States battleship sank near Havana). Led by New York Journal publisher William Randolph Hearst, American newspapers expressed outrage about the tragedy, arousing public opinion for the U.S. to go to war with Spain (The Maine Blown Up, New York Times article from February 15, 1898).

O caso Maine na Prensa Amarela USA, by New York Journal, Public Domain

Front Page from the New York Journal, February 17, 1898

A subsequent naval court of inquiry concluded that the ship was destroyed by a submerged mine, which may or may not have been intentional. Most recent historical research suggests the cause of the explosion was an accidental fire in the ship’s coal bunker. No one is certain what actually happened. Still, fueled by the sensational yellow journalism headlines and news stories, the United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. That war resulted in the United States acquiring the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico as territories and launching America as a global power.

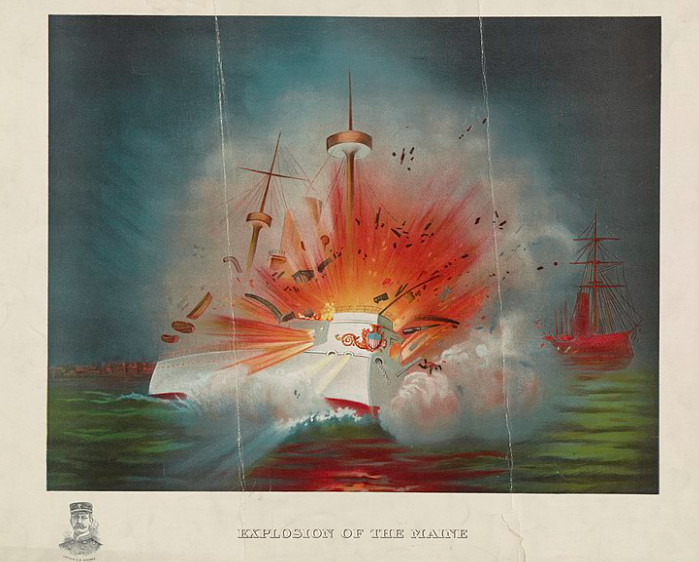

Explosion of the Maine, Library of Congress, Public Domain

Explosion of the Maine, Library of Congress, Public DomainYou can learn more about the course and consequences of the Spanish-American War on the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page: America's Role in World Affairs.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Assess the Historical Impact

- Review:

- Discuss:

- How did yellow journalism create a climate of support for the Spanish-American War?

- How did yellow journalism impact people’s emotions and thoughts?

- What propaganda techniques did William Randolph Hearst use to create public support for war?

- What examples of yellow journalism can be found in the media today?

- Write a Yellow Journalism Style News Article

- Compose a yellow journalism article about a current topic or issue in the news.

- Include a headline and an image that appropriately fits the topic.

- Have the class vote on a title for the newspaper.

- Put the articles together in a digital format using LucidPress or Google Docs.

- Analyze a Source

- Select an article from the National Enquirer or a similar tabloid magazine and identify how the article is an example of yellow journalism.

3. ENGAGE: How Can Students Become Fact Checkers Who Evaluate the Credibility of News?

Why is there an abundance of fake and false news? One answer is that creating fake news is both very easy and highly profitable. The Center for Information Technology & Society at the University of California Santa Barbara identified the simple steps individuals or groups can follow in creating a fake news factory:

- Create a Fake News Site: Register a domain name and purchase a web host for a fake news site (this is relatively inexpensive to do). Choose a name close to that of a legitimate site (called “typosquatting” as in Voogle.com for people who mistype Google.com). Many people may end up on the fake news site just by mistyping the name of a real news site.

- Steal Content: Write false content or simply copy and paste false material from other sites, like the Onion or Buzzfeed.

- Sell Advertising: To make money (in some cases lots of money) from fake news, sell advertising on the site. This can be done through the web hosting platform or with tools like Google Ads.

- Spread via Social Media: Create fake social media profiles that share the posts and post articles in existing groups, like "Donald Trump For President 2020!!!"

- Repeat: "The fake news factory model is so successful because it can be easily replicated, streamlined, and requires very little expertise to operate. Clicks and attention are all that matter, provided you can get the right domain name, hosting service, stolen content, and social media spread" (CITS, 2020, para. 21).

For social media platforms, fake news is good business. Attracted by the controversies of fake news, users go online where they encounter not just misinformation, but advertising. Business organizations pay the social media sites huge amounts of money to get people to view their ads and to access the data of those online. In 2019, for example, 98% of Facebook revenue came from advertising (Facebook Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2019 Results).

While there is much fake news online, it is shared by a very small number of people. Looking at the 2016 Presidential election, researchers found that less than 0.1% of Twitter users accounted for sharing nearly 80% of fake and false news during the 2016 election (Grinberg, et. al., 2019). Interestingly, those over 65-years-old and those with conservative political views shared considerably more fake news on social media than members of younger age groups (Guess, Nagler & Tucker, 2019).

Media Bias/Fact Check Wordmark/Public Domain

Media Bias/Fact Check Wordmark/Public DomainFact checking

Happening both online and in-print, fact checking involves examining the accuracy of claims made by politicians and political groups and correcting them when the statements are proven wrong. News and social media organizations now devote extensive resources fact checking. One report, the Duke University Reporters' Lab Census, 2020, lists some 290 fact-checking organizations around the world. Yet, even though statements made by individuals or organizations are evaluated by journalists and experts, final decisions about truth and accuracy are left to readers and viewers. Given the enormous amount of fake and false information generated every day, fact checking has become an essential responsibility for all citizens, including students and teachers, who want to discover what is factual and what is not.

Sign-up for The Washington Post Fact Checker here.

Access CNN Politics Facts First here

Access FactCheck.org here

Sam Wineburg (2017) and his colleagues at Stanford University contend that while most of us read vertically (that is, we stay within an article to determine is reliability), fact checkers read laterally (that is, they go beyond the article they are reading to ascertain its accuracy). Using computers, human fact checkers open multiple tabs and use split screens to cross-check the information using different sources. Freed from the confines of a single article, fact checkers can quickly obtain wider, more critically informed perspectives by examining multiple sources.

The importance of fact-checking raises the question of whether social media companies should engage in fact-checking the political and government-related content posted on their platforms. Proponents of social media company fact-checking contend that Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and others have resources to uncover false and misleading information that everyday citizens do not. Still, social media companies have been reluctant to comment on the accuracy of content on their sites.

Fact Checking Donald Trump

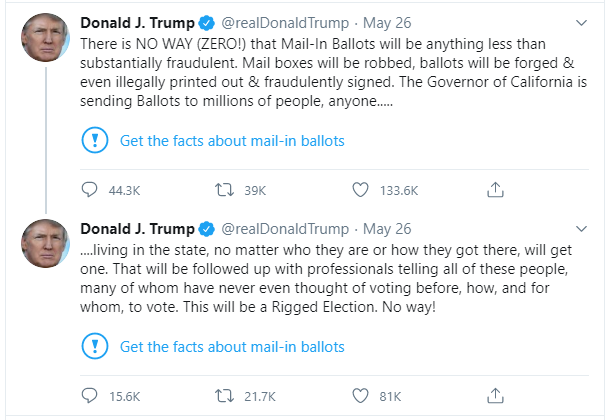

President Trump's Tweet, May 26 2020

President Trump's Tweet, May 26 2020On May 26, 2020 however, Twitter for the first time fact-checked tweets about mail-in voting made by President Donald Trump (MIT Technology Review). Trump claimed that California's plans for voting by mail would be "substantially fraudulent." Twitter's CEO Jack Dorsey responded that the President's remarks violated the company's civic integrity policy, stating that the tweets "contain potentially misleading information about voting processes." Twitter posted a "Get the Facts about Mail-In Ballots" label next to the tweets and included a link to summary of false claims and responses by fact-checkers.

Two days later after nights of rioting and protests in cities around the country following the death of an African American man in police custody in Minneapolis, the President tweeted "when the looting starts, the shooting starts." Twitter prevented users from viewing that Presidential tweet without first reading a warning that the President's remarks violated a company rule about glorifying violence. It was the first time Twitter had applied such a warning to a public figure's tweets but did not ban the President from the site because of the importance of remarks by any important political leader (Conger, 2020).

Twitter's actions unleashed a storm of controversy with supporters of the President claiming the company was infringing on the first amendment rights of free speech. Trump himself issued an executive order intending to limit legal protections afforded tech companies. Supporters of Twitter's actions saw the labeling as an example of responsible journalism in which people were urged to find out more information for themselves before deciding the accuracy of the President's claims.

Finally, following the violent January 6, 2021 insurrectionist attack on the Capitol, Twitter permanently suspended Donald Trump from its platform. Other major social media sites also took steps to ban or restrict Trump (Axios, January 11, 2021). Read here how different free speech experts viewed these policies.

You can find more information about the debates about the role of social media companies in dealing with misinformation in the Engage module for Topic 7/Standard 6.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Compare and Contrast: Fact Checking Sites and Tools

- Identify each fact checking site's strengths and drawbacks:

- Practice Fact Checking

- Investigate online or in-print articles on a topic or an issue and explain your judgments about what is accurate and not accurate in these publications.

- Learn Online

- Play Newsfeed Defenders from iCivics

- This online game teaches students to uncover deceptive and false online claims.

Online Resources for Fake News & Fact Checking

- BOOK: Donald Trump and His Assault on Truth: The President's Falsehoods, Misleading Claims and Flat-out Lies. The Washington Post Fact Checker Staff, Scribner, 2020

- This book examines 16,000 false statements made by Trump in tweets and at press conferences, political rallies, and television appearances during his first three years as President.

- How Do Fake News Sites Make Money, BBC News

- We Tracked Down a Fake News Creator in the Suburbs. Here's What We Learned, All Tech Considered (November 23, 2016)

- Turn Students into Fact-Finding Web Detectives by Common Sense Education offers strategies to prepare students to be fact-checkers.

- Twitter Users & The First Amendment: Can Public Officials Block Political Dissenters on Social Media?

- In May 2018, a federal district court in New York state ruled public officials cannot "block" people from responding to content posted on the @realDonaldTrump Twitter account.

- A Tale of Two Elections: CBS and Fox News' Portrayal of the 2020 Presidential Election. Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy (December 17, 2020).

- Over the course of the full 2020 campaign, Trump received four times as much coverage as Biden on CBS and three times as much on Fox.

Standard 7.5 Conclusion

This standard’s INVESTIGATE examined fake news - information that creators KNOWS is untrue, but which they portray as fair and factual. UNCOVER showed that fake news is not new in this century or the current political divide in the country, featuring examples including Benjamin Franklin’s propaganda during the American Revolution, efforts to sell newspapers during The Great Moon Hoax of 1835, the use of yellow journalism in the form of exaggerated reporting and sensationalism in the Spanish-American War, and present-day disinformation and hoax websites. ENGAGE asked how online Fact Checkers can serve as technology-based tools that students and teachers can use to distinguish credible from unreliable materials.