The Basic Evaluation Process.

Evaluations are often needed to make informed decisions. The basic process for any evaluation requires that you:

- Describe the evaluand (what is being evaluated),

- Determine the purpose for the evaluation (what do you want to know),

- Establish criteria for judging the evaluand and the relative importance of each criterion,

- Determine the best sources and methods for obtaining requisite information, then

- Collect data, analyze results, and make recommendations

Sounds simple enough. However, the more closely you look at each aspect of the process the more you will appreciate the complexity of planning and carrying out a good evaluation. There are several things to consider.

Evaluator Titles and Jobs

While it is true that everyone conducts informal evaluations all the time, it is also true that those who conduct formal evaluations do not always identify themselves as evaluators.

Most jobs require evaluation skills and abilities; not all job descriptions specifically articulate this as a requirement. People conducting evaluations as a part of their job go by various names and titles. Some of these include – auditor, assessor, analyst, judge, compliance officer, arbitrator, counselor, consultant, director, specialist, manager, supervisor, and advisor. Specific jobs for evaluators in educational settings include – evaluator, teacher, the office of teaching effectiveness and innovation, instructional designer, training and support coordinator, evaluation and research assistant/associate/specialist, director of evaluation and assessment, curriculum specialist/director, program manager/coordinator, assessment/data analyst, and institutional researcher.

Internal and External Evaluators

We should also make a distinction between internal and external evaluators. Internal evaluators, those working within an organization as evaluators, work as full- or part-time employees. When evaluators work as consultants, completing as-needed contract work, they are referred to as external evaluators. There are benefits and disadvantages to both.

When an organization is committed to evaluation and the benefits of continuous improvement, and the organization is large enough to warrant hiring full-time evaluators, it can be cost-effective and efficient to have internal evaluators on staff. Internal evaluators can develop an in-depth understanding of the organization, its purpose, goals, politics, structure, and personnel. They have access to the information and informants they need to do their job and can work on several interrelated evaluation projects (of various sizes and scopes) within the organization. This can be extremely beneficial to an organization. However, internal evaluators can become biased or jaded. They may begin to advocate for specific solutions for political reasons or base findings on unimportant criteria. If internal evaluators do not have some degree of autonomy or do not develop and maintain solid evaluative thinking abilities, professional ethics, appropriate soft skills, and healthy relationships with those they serve, their evaluation efforts can be ineffective and impeded by others in the organization. Above all, evaluators need to be trusted.

External evaluators are sometimes needed for various reasons. At times the evaluation needs of an organization exceed the capacity of internal evaluators. Those in the organization may not have time or expertise to complete a required evaluation. It can be cost-effective and prudent to hire an external evaluator to provide professional services on an as-needed basis. Sometimes, for political reasons, an evaluation needs to be perceived as unbiased and objective. An external evaluator’s reputation as a competent ethical evaluator can provide the organization with results other stakeholders and the general public can trust. There are, however, challenges an external evaluator may face. An external evaluator needs to gain an understanding of the organization’s goals and structure. They (or the evaluation team) need to develop relationships, get access to information and informants, understand how an individual project fits into the overall picture and the reasons the evaluation is being commissioned (i.e., needed).

Working with Clients

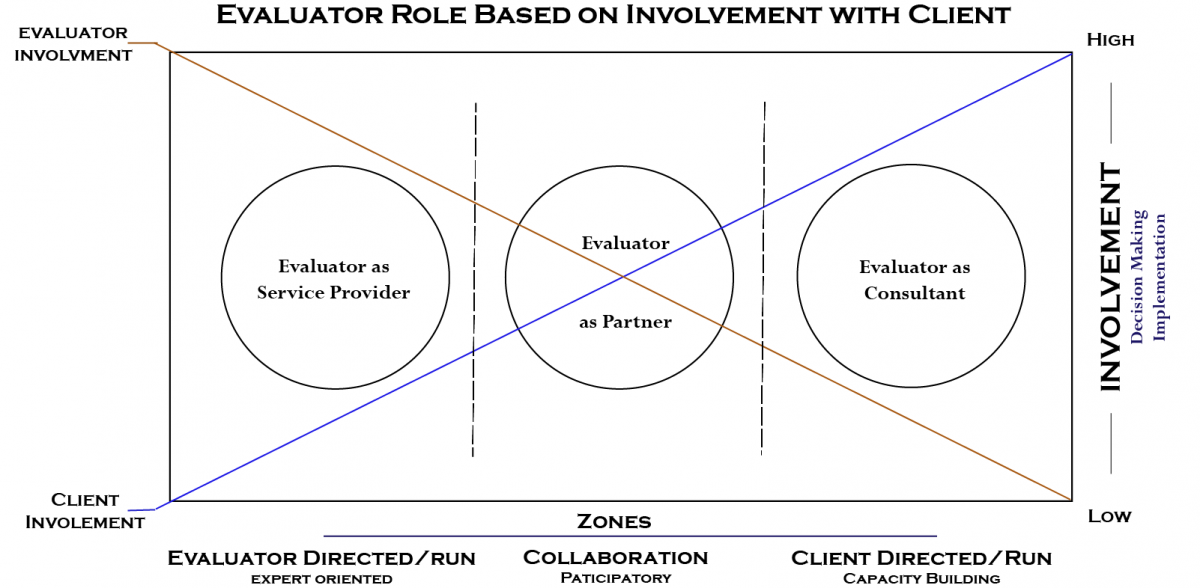

You will recall that one of the main differences between research and evaluation has to do with the role the principal investigator plays in terms of who is responsible for making final decisions regarding the inquiry’s design (i.e., purpose, questions, and methods). Researchers typically work for themselves (i.e., they are in charge) while evaluators work for clients. There are exceptions, for example when a researcher works on an institutional research team or when an evaluator is conducting evaluation research. Still, evaluators typically work for a client as a service provider, on an evaluation team, or as an independent consultant. We use the term client as a broad description referring to the person commissioning an evaluation project. The client may be a supervisor or manager who assigns the project to an internal evaluator or a team of evaluators. The client may also be an employer hiring an external evaluator to conduct a specific evaluation. In either case, the role of the evaluator can be characterized by the involvement they have in the decision-making process and their responsibilities in implementing the evaluation. The relationship between the evaluator’s involvement in the project and their role is depicted in Figure 1.

Service Providers. When the evaluator is hired as an external consultant or is the director of a department, and they have an extensive say in determining the purpose, goals, and questions for an evaluation, as well as, the methods utilized to complete the evaluation, they might best be described as a service provider. In these cases, the evaluator (or their team) is typically responsible for the implementation of the evaluation. They will then report back to the client once the evaluation is completed.

Evaluation Partner. An evaluator may work as a partner with a client. This is what Patton (2010) calls developmental evaluation. The evaluator may be working as an internal or external evaluator, but when the evaluator’s role is one of partner, the control and the implementation of the evaluation responsibilities are shared between the client and evaluator.

Evaluation Consultants. An evaluator may also be hired solely as a consultant. In these situations, the evaluator lends their expertise to recommend the best way for the client to complete the evaluation. The evaluator may supervise and train individuals as they complete various evaluation activities. The purpose of an evaluator serving in this role is to build capacity and put in place needed evaluation processes so the organization can conduct its own evaluations without the evaluator in the future. Stufflebean (2014) warns however that this type of evaluation may become a pseudo-evaluation if the evaluator is expected to simply sign off on the evaluation as if the evaluation was completed by the evaluator and not the client.

Figure 1: Evaluator Role by Involvement. |

| |

Evaluations should not be cast into a single mold [scientific].

For any evaluation, many good designs can be proposed, but no perfect ones.

Cronbach (1982)

Making Plans and Proposals

The main difference between a plan and a proposal is the amount of detail required. Depending on who the evaluator is working for, a proposal need not include a detailed evaluation plan. Suppose you are working as an internal evaluator. In that case, your proposal needs to be clear, concise, and detailed enough that your employer/supervisor (i.e., the client) would sign off on your vision for completing the evaluation. However, if the evaluator is competing for an evaluation through a requestion for proposals (RFP) process, the plan may need to be quite detailed as the proposal will form the basis for an evaluation contract. In cases like this, you must persuade the client that your proposal is the best one submitted, and the prospective client should hire you to complete the evaluation. Once a proposal has been accepted, a more detailed plan may be needed to manage the project properly. Project management plans will include specific details regarding the project tasks, data collection, and personnel assignments.

Pre-Planning Activities

Before producing a proposal or plan, it is essential to clarify the client's request. It can take some time to fully understand and clarify the context, conditions, and potential value of conducting an evaluation. You will need to consider several things before deciding to proceed with an evaluation. To properly conduct an evaluation, you will need to fully understand the situation. Asking specific questions can facilitate this process.

Context considerations.

- Who is requesting/funding the evaluation?

- What do they want to know? Why do they want to know?

- Who are the decision-makers? Other important stakeholders?

- Are there political considerations that may affect the evaluation?

Often the evaluation context can be complicated. Many educational initiatives and programs are sponsored (funded) by one entity, managed by someone else (often the client), implemented by several individuals (concerned stakeholders), and intended to benefit a diverse group of end-users. Likewise, the reasons for commissioning an evaluation can be varied. Politics is often involved. Sometimes the client has a hidden agenda; they may want the evaluation to justify or support a preferred decision or course of action. Various stakeholders may have different reasons for wanting the evaluation and may intend to use the evaluation results to inform a variety of decisions. To avoid problems, the evaluator must understand the context.

Understand the Evaluand.

Work with the client to fully understand what is to be evaluated. You might ask:

- What is its purpose?

- How does it work? How is it supposed to be used?

- Who are the intended users? Why is it needed? What are the intended outcomes?

- If the evaluand is a program, who is responsible for implementing the program?

- What is the evaluands current stage of production?

Evaluators need to gain a thorough understanding of the things they will be evaluating. Not only will they be required to describe the evaluand, but they will not be able to make valid recommendations without understanding the product and how the designer intended it to be used. Some evaluators use a logic model to accomplish this task. When evaluating an educational product, knowing where the product is currently in the design and development process can also inform the kinds of evaluation needed.

Constraints and Requirements.

- What is the timeframe for completing the evaluation?

- How much funding has been allocated for this project?

- Who will serve as your contact person? With whom will you be working?

- What resources will be available (personnel, equipment, supplies)?

- Will you have access to the information and informants you need?

- Are there any specific requirements and expectations?

It is likely that any evaluation you attempt can be conducted successfully to some extent. We say "likely" and "to some extent" because we do not live in a perfect world; we often lack sufficient resources, and sometimes we lack the desire or ability to complete requisite evaluation activities.

Consider the following common evaluation constraints and issues:

Desire. This can be a constraint when working for a client or with an evaluation research team. You may be willing and interested in completing a rigorous systematic evaluation, but the client (who has commissioned the evaluation), for legitimate reasons, may only be interested in paying for answers to a few specific evaluation questions.

Feasibility. In addition to desire, feasibility can be a constraint. For example, the preferred data collection method may not be possible. When this happens, compromise is required, and, in some cases, the activity may need to be abandoned.

Ability. People often describe evaluators as a generalist. While an evaluator may have many skills and abilities, they may not be an expert when it comes to specific competencies. Skills and abilities can be developed, but if an evaluator cannot competently complete a specific evaluation task, they will need to recruit (hire) someone to help or be satisfied with the possibility of getting a less than perfect outcome.

Time. This is a prominent issue in evaluation practice. Time is usually of the essence; however, a specific window of opportunity often constrains our ability to capture data. For example, you can only get student achievement data once learners have finished taking their course and the final exam. This means an evaluator may have to wait several months to get the required data needed to complete an evaluation. In addition, some data collection practices take time to complete and are more costly to accomplish (e.g., interviews and observations). An impact evaluation can take months, if not years, to track participants longitudinally. If an evaluation needs to be completed within a specific time frame, evaluators may need to prioritize what can and will be done within that time limit.

Money. This is a constraint because clients (employers) have limited funds. Some evaluators are willing to work for free, but others wish to be compensated for their services (soft costs). In addition, there are always some hard costs associated with conducting an evaluation. These include the cost of travel, facilities, equipment, and supplies. These costs are sometimes forgotten when the evaluator is an internal service provider, but they exist nonetheless.

Access. When you plan evaluations, you might proceed under the assumption that you will have unlimited access to the data sources needed to complete the evaluation properly; this would be a mistake. In practice, evaluators must deal with many restrictions associated with data access. Ethical constraints prohibit evaluators from coercing or forcing individuals to provide information. Not everyone is willing to be a study participant, or you may need to get permission to collect data from potential informants (e.g., vulnerable populations). Sometimes the data you wish to use exists, but those controlling access to the data are unwilling to give it to you because of the regulations they must follow or the cost of providing that information.

Additionally, there are times when the data you need does not exist and cannot be easily obtained. You may lack access to key informants, or it is difficult to obtain accurate measures of the data you need because you do not have access to existing instruments or no suitable measurement instruments exist. At other times, those providing the information may not provide accurate information. For example, early elementary-aged children may not have the meta-cognitive capacity to understand and communicate their motives, likes and dislikes, goals and aspirations. Other participants may be unwilling to answer honestly because they are suspicious of an evaluator's motives; they may also provide skewed information for personal reasons. For example, they may (unintentionally or otherwise) downplay flaws in a product they value. Gaining access to and obtaining valid, relevant data can be one of the most significant limitations of any evaluation.

Not all evaluations can or should be conducted

Evaluability Assessment.

Part of any evaluability assessment involves understanding the evaluand's current stage of development and circumstances surrounding the product's use. The other part involves determining if an evaluation is warranted. Not all evaluations are worth doing. There are several situations where careful consideration should be taken to decide whether conducting a formal evaluation is sensible.

- Nothing new to know. In some situations, the cost of completing a formal evaluation is not warranted because the probability of obtaining any new (i.e., useful) information is unlikely. This can happen when a product has been studied extensively, and its value has already been established. This can also happen when it is evident that research concerning the pedagogical theories and design principles underpinning the product does not support the product's development or its implementation. It may be hard to justify re-evaluating a product in such cases. There are exceptions as the results of many research studies cannot be replicated consistently. An evaluation of well-studied products may produce new information when circumstances and conditions change substantially over time. For example, a considerable amount of evaluation research was conducted to determine the potential efficacy and effectiveness of online learning. Much of this research concluded that online learning was less effective than in-person learning due to inadequate pedagogies and the lack of technology needed to successfully implement online learning. However, conditions and circumstances have changed considerably from when this research was initially conducted—improvements in online technologies and increased access to technologies by learners in many locations have made online learning a viable and effective alternative to in-person learning. In cases like this, changing circumstances may make conducting new evaluations reasonable.

- Trivial results are expected. The value of conducting an evaluation might be suspect if the purpose and scope of the evaluation are insufficient or limited in some significant way. For example, if a proposed effectiveness study to determine whether a product or program facilitated student achievement was needed, but the evidence to be collected was only to consider parents' perceptions of their student's learning. Results, in this case, represent a trivial facet of effectiveness and would likely be misleading. Without a more robust and systematic data collection process, an evaluation of this type might not be beneficial.

- The product is not needed. An evaluation may not be necessary if other similar popular products exist and there is no interest in the product being proposed as the evaluand. When few users adopt a product, it may be difficult to conduct some kinds of evaluation (e.g, effectiveness and impact). Not only that, depending on how similar the product is to other already tested products, results for a usability evaluation may be somewhat inconsequential. A marketing evaluation might benefit a designer to know why people choose other products, but an extensive evaluation of the product may be futile given the lack of interest in the product and its similarity to other existing products.

- The product cannot be used. In some situations, you may find that users do not use a product not because they don't want to but because they cannot. For example, in many places throughout the world, learners do not have adequate access to the internet. It would be unwise to evaluate a product that depends on internet access in these areas.

- Results are unlikely to be used. Many educational programs have a limited lifespan. For various reasons, stakeholders may decide to discontinue an initiative regardless of any results an evaluation might provide. Sometimes effective programs are discontinued because the person championing the program leaves, the cost of implementation becomes too great, or the funding for the program runs out. When there are no plans to continue an initiative for one of these reasons, conducting an evaluation may be unimportant. In addition, you may not be surprised to hear that some evaluations are commissioned for political reasons. At times a client commissions an evaluation to avoid making a decision or to make it look like something is being done while all along having no intention of using the evaluation results.

- There is nothing to evaluate. In some cases, certain kinds of evaluation cannot be conducted because the product is only a concept or is still in development. If the product is likely to undergo substantial changes during the design and development phases, effectiveness evaluation and impact testing may need to be postponed until the product is stable enough to be evaluated.

There are certainly many reasons why an evaluation might not be warranted; those presented here are but a few. However, once you determine that an evaluation is viable and needed, you can now start planning the evaluation and developing a proposal.

Creating an Evaluation Proposal

Description of the evaluand.

An evaluation proposal (or plan) often starts with a description of (or introduction to) the evaluand, the client, end-users, and important stakeholders (i.e., those directly associated with the implementation of the product or with a vested interest in the product's use). Information gathered from the pre-planning phase will be indispensable in accomplishing this task.

For evaluation in an educational setting, the evaluator needs to describe the purpose and function of the instructional product, how the designer intended it to be used and who the intended users are. It may include an explanation of the theory and principles supporting the product's design and any contextual aspects relevant to the product's use. If the product has not already been developed and implemented, the introduction section of the proposal should explain the product's current status in the design and development process. Often, evaluators are asked to serve as external evaluators for a funded development project. In these cases, the evaluator may propose various evaluation activities appropriate for each stage of the product's development. For example, it is typical for a developmental evaluation to focus on formative evaluation activities during the project's initial months (or years), then switch to summative evaluation activities once the product's development has been completed and the product has been implemented in its final form. This may include efforts to establish the effectiveness and impact of the product. It may also include a negative-case evaluation to determine which users benefit from the product and which do not.

Write a purpose statement.

A purpose statement describes the reason (or need) for the evaluation. This statement will explain the decisions a client needs to make and how evaluation results will be used to inform these decisions.

Sometimes the purpose for an evaluation is provided for you by the client. Other times, all the client knows is that they need or want an evaluation of a specific product. Some clients may be asking for the evaluator's expertise to help them determine a valid and viable purpose for the evaluation. Other times the evaluator needs to suggest utilizing various types of evaluations to answer questions they may not have considered. For example, it is not uncommon for clients or interested stakeholders to ask for a summative evaluation of the effectiveness and impact of an educational product. This may sound reasonable, but if the evaluand has not yet been developed or has yet to be implemented, these types of evaluation may not be possible. Likewise, it is often the case that an evaluator needs to suggest alternative or additional reasons and purposes for evaluating a product. For example, while an objectives-oriented evaluation of the product's effectiveness might be beneficial, an implementation evaluation may be needed as well. An implementation evaluation provides evidence that an educational product can be and is being used as intended or that a program is being implemented properly. Without this, clients, decision-makers, and other interested stakeholders will often misinterpret and possibly misuse the results of an effectiveness evaluation. Misunderstanding results can adversely affect the decisions people make.

When deciding on a purpose for an evaluation, you need to consider all the possibilities then establish an appropriate yet feasible reason for conducting the evaluation. The purpose you eventually decide on will be influenced by context, situation, and existing constraints. However, initially, you should ignore constraints and brainstorm ideas as if anything were possible (divergent thinking). Think about everything you would like to know about the product you plan to evaluate. Consider what you would need to do to answer these questions. After identifying all the possibilities, determine which are essential (need to know objectives) and which are less critical (nice to know objectives). Consider constraints to narrow the evaluation purposes and scope (convergent thinking). The purpose you ultimately decide on will often represent a compromise between what you would like to do and what is possible. The purpose of any evaluation should represent an important reason or need.

List Evaluation Questions and Specify Criteria

An evaluation proposal should list specific evaluation questions needed to inform the decisions proposed in the purpose statement. Your proposal should also include a description of the criteria you will use to judge the merit and worth of the evaluand. Sometimes all the questions and criteria are deemed essential but not always. In these cases, the evaluator should prioritize the questions and criteria by importance. For example, the primary evaluation question might ask how successfully a product facilitates students' achievement of specific expected learning objectives. A secondary question (i.e., an important but not essential question) might ask in what ways the product might be improved to increase its utility. The effectiveness criterion is primary, and the usability criterion is secondary.

Types of standards/criteria

You will recall that a standard is a generally accepted set of criteria used to make a judgment. In contrast, a criterion may represent a personal value held by individuals but not generally agreed on as essential or even necessary. Criteria can be classified as rules and requirements, a scoring structure, or specific principles and attributes individuals value. Criteria commonly used to judge educational products include utility, usability, feasibility (viability), availability, cost, effectiveness, efficiency, impact, satisfaction, preference, desirability, relevance, coherence, social acceptability, safety, and sustainability, to name a few. Evaluators may use some or all of these criteria to judge the merit and worth of an educational product or program. However, some of these will be more important than others to decision-makers. For example, decision-makers may value effectiveness and efficiency over user preference and product appeal. Indeed, a product that works is better than one that does not, even if it looks good. Still, individuals may not use a product they find unappealing even if it is more effective than other more attractive products. So while it may be unimportant to decision-makers that users like the look of a product, it still could be an important criterion for evaluating a product – or not.

Proposing Data Collection Methods

Once evaluation questions have been established, an evaluator must determine what data is needed to answer the evaluation questions. They must then propose sensible data collection procedures that could be used to capture the required data. Proposed methods will include identifying the sources (e.g., the people, existing data, documents) from which the data will be retrieved. It will also describe the procedures required to obtain the data and how the evaluator will analyze the data. Precise detail need not be included in a proposal. Still, enough specificity should be provided to convince the client that the data collection efforts will likely produce enough relevant information to answer each of the evaluation questions. For example, it would be insufficient for a proposal to only say that interviews and surveys will be used to collect data. The proposed methods should include some details regarding who will be interviewed and surveyed, what instruments will be used, how data collection instruments will be developed, and how the data obtained will be analyzed and used to answer the evaluation questions.

Determining a Budget

Developing a budget can be tricky, especially when the evaluator is an external evaluator responding to a request for proposals. Budgeting too little will mean you may be doing the evaluation for free, or worse, you may have to pay out of pocket to complete the evaluation you contracted to do. Asking too much may diminish your chances of obtaining work now or in the future. Understanding actual costs and how much you are willing to charge for your services is essential to the budgeting process. However, budgeting issues can be alleviated to some extent by asking clients upfront what they have budgeted for the evaluation. Knowing beforehand any budget restrictions can allow the evaluator to plan activities and limit the scope of the evaluation accordingly. Giving a client the option to include or exclude certain costly activities they are unwilling or unable to pay for can also help.

As mentioned previously, there are soft costs and hard costs that need to be considered. Soft costs represent the evaluator's time, and hard costs represent the cost of travel, facilities, equipment, and supplies. These costs are sometimes forgotten when the evaluator is an internal service provider, but they exist nonetheless. When working as an internal evaluator, budgeting usually entails specifying the personnel required and estimating the time needed to accomplish each task.

Getting Proposals Approved

Often external evaluators have to submit a proposal and hope for the best. However, the evaluator can sometimes negotiate terms and requirements with the client beforehand or after submitting a draft proposal. Working collaboratively with the client on the proposal's details can be a very productive way to develop an evaluation plan. Once a proposal is approved, a more detailed management plan will likely be needed.

Chapter Summary

- Evaluations are conducted within the context of a specific situation. The purpose and methods may vary as time, available resources, and politics constrain what can be done.

- Evaluation plans and proposals are similar, but a proposal can be less detailed. Once a proposal is accepted, a more detailed management plan will be needed.

- Plans are essential but often need to be adapted to account for changing circumstances and conditions.

- Pre-planning activities are necessary to properly understand the context, conditions, and potential value for conducting an evaluation.

- An evaluator needs to carefully consider whether an evaluation can or should be done.

- A proposal needs to include a description of the evaluand, a purpose statement, proposed methods, a timeline, and a budget.

- Establishing an evaluation's purpose requires divergent and convergent thinking to determine an achievable yet meaningful objective for the evaluation.

- A purpose statement describes the reason an evaluation was commissioned. It explains the decisions that need to be made and how evaluation results will be used to inform these decisions.

- Proposed methods should be viable and likely to produce sufficient data to answer the evaluation questions.

- Timelines and budgets are needed to ensure the planned activities can be accomplished within the timeframe specified for the evaluation and within any existing funding constraints.

- Pseudo-evaluations should be avoided as they are conducted to promote a specific predetermined solution. These include politically-inspired and advocacy-based evaluations.

- Quasi-evaluations provide good information, but the value of the findings is limited in some way. Evaluation classified as quasi-evaluations could be improved by expanding the scope of the evaluation and the criteria used to determine merit and worth.

Discussion Questions

- Provide an example of an evaluation you would likely choose to decline. Give reasons why you would be hesitant to take on such an evaluation.

- Suppose a client asks you to help them with an evaluation project. Describe the benefits and disadvantages of working as a service provider, evaluation partner, or consultant. Which would you prefer and why?

- Think of a specific educational product you have used or would like to use. For that specific product, describe any questions that need answering before you could develop an evaluation proposal for that product. Provide possible answers to these questions.

- Imagine a fictitious client asks you to help them evaluate a product they have developed. Using a divergent thinking process, list various types of evaluation the client might employ and the benefit of each in terms of decision-oriented questions that could be answered. Using a convergent thinking process, consider potential constraints that would limit the viability of each of these evaluation options.

References

Cronbach, L. J., & Shapiro, K. (1982). Designing evaluations of educational and social programs. Jossey-Bass,.

Patton, M. Q. (2010). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford press.

Stufflebeam, D. L., & Coryn, C. L. (2014). Evaluation theory, models, and applications (Vol. 50). John Wiley & Sons.