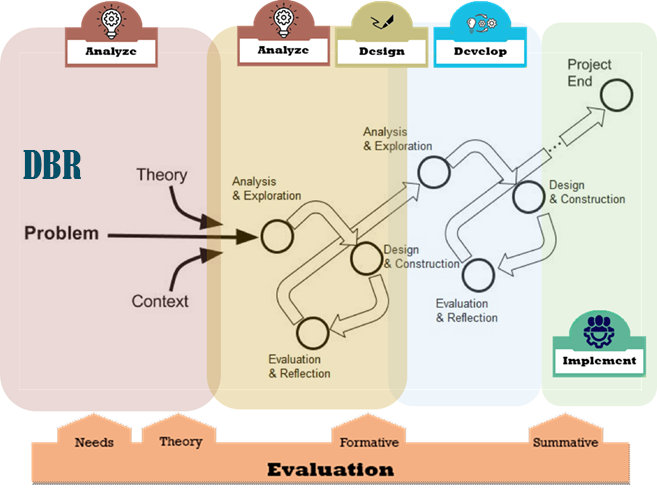

While instructional designers commonly conduct formative evaluations in the development phase, formative evaluations are also common in the other phases when creating instructional products. For example, in design-based research (DBR), formative evaluation is prominent in both the design and development phases but also can occur in the analysis phase (see figure 1). It can be part of prototype testing in the design phase or a beta testing process in the development phase. In practice, designers continually evaluate a design's effectiveness, efficiency, and appeal throughout these stages; it is good practice to begin user testing early in the design and development process.

Figure 1: Evaluation Integration within a Design Based Research Model. |

The evaluations carried out in the development phase are often short but numerous as hundreds of design decisions need to be made. The products we evaluate are typically beta versions; the final version may become something entirely different. Evaluation in this phase helps refine the product to the point that it is good enough to implement, even if it is not perfect. The implemented product needs to be an adequate solution to the instructional problem (i.e., gap or need), not a perfect solution. Although, even if a product works, it also needs to appeal to the user.

User Testing (formative evaluation)

User testing involves getting information from actual users (view video). We are not testing the users; we are testing the product's design and how users interact with the product. We want to know what they need and want the product to do. This is why many call this usability testing. The concept of user testing is based on human-centered design principles and the idea that products are designed for people to use. Human-centered design requires product developers to empathize with the end-user, understand their needs, and build products they want and enjoy using. To do this, designers need user input and formative evaluation.

We use many labels to describe the evaluation activities performed in this stage of production; all are related and often represent distinctions without a lot of difference. For example, user experience (UX) testing and usability testing both fall into a broad category of User Testing.

UX testing vs Usability testing

Often people use the terms usability and UX testing interchangeably. User testing was the original term, followed by usability testing. UX design testing is the more recent term and is debatably more widely used.

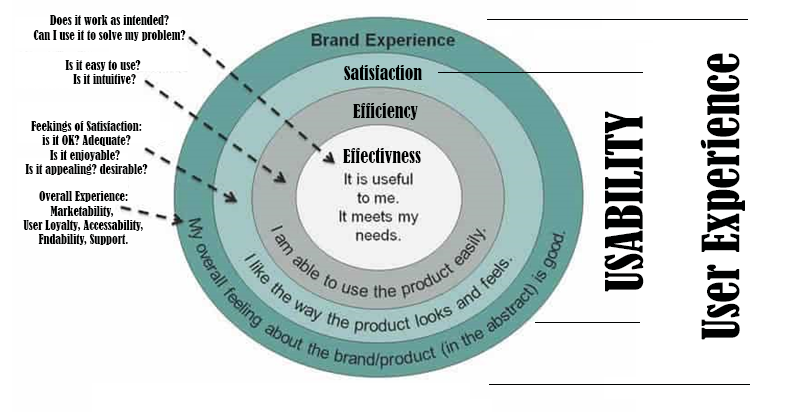

Some definitions suggest usability is concerned only with functionality, ease-of-use, and learnability (i.e., how intuitive the product is to use). They define UX design (and testing) more broadly to include usability, but also additional aspects of the end-users experience associated with marketing, branding, findability, support, accessibility, and overall appeal (see Figure 2, adapted from).

Figure 2: Usability and UX Design Testing. |

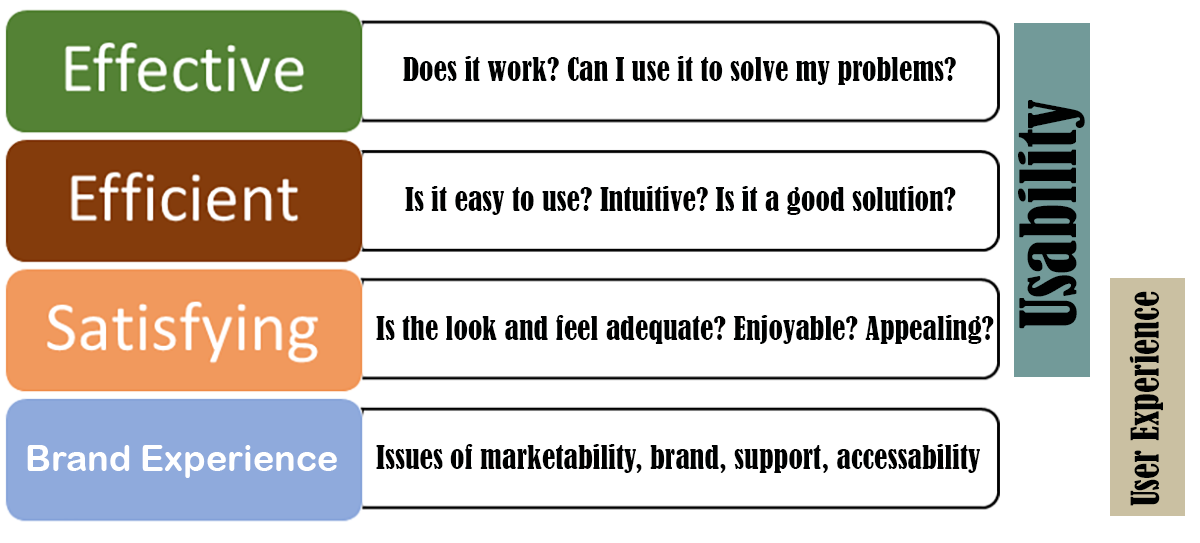

However, the International Standards Organization (ISO) defines usability in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction (ISO 9241-11, see video). Some suggest that a product can be desirable and not be useful or usable—making UX design a subset of usability or perhaps just overlapping constructs (see Figure 3). The difference is framed as a contrast between science (i.e., usability) and art (i.e, user experience). Those purporting that usability and user experience are different describe usability as analytical, while user experience is subjective; They suggest usability focuses on users' goals, but user experience focuses on how it makes the user feel.

So the main distinction seems to be how you interpret the term satisfaction. Satisfaction meaning "good enough" (i.e., it's functional, I am pleased with how it works), or satisfaction meaning "desirable and appealing" (it works well, AND I love how it looks and how it makes me feel).

Figure 3: Usability and UX Design Testing. |

You can decide for yourself the degree to which these terms are similar or different and what you want to call the evaluation activities you perform in this phase of a product’s development. In terms of how formative evaluation benefits the design and development process, we need to consider several issues.

Evaluation Criteria and Purpose

The purpose for usability and UX testing vary, but the evaluator’s goal usually is to:

- Identify problems in the design of the product or service,

- Improve the functionality or quality of the product to enhance the product’s performance and increase user satisfaction,

- Uncovering opportunities to add features or deal with users’ un-met needs,

- Learn about the target user’s behavior and preferences, or

- Determine how satisfied users are with the product.

UX experience and usability testing both use three general factors or criteria to judge the product's value, merit, or worth.

- Effectiveness – The primary criteria for determining effectiveness are utility and usefulness. Judging effectiveness requires that you answer questions like: Does the product work? Does it do what it was designed to do? Can I use it to solve my problem? Is it useful?

To capture this information, you will need to observe how well users utilize the product to solve a specific problem or complete a task.

- Efficiency – The primary criteria for determining efficiency are ease of use or usability. Can the product be used as intended? Is the design elegant? Intuitive? Fast?

To capture this information, you will need to observe how users interact with the product.

- Satisfaction – The essential criteria used to evaluate satisfaction are varied. Satisfaction is subjective and depends on one's values (i.e., what is most important to the individual). Basic satisfaction might be determined by the product's usefulness and utility; however, deeper levels of satisfaction might consider the product's safety, cost, support, presentation, and overall appeal. Evaluation efforts primarily focus on the users' experience. How do users feel about the product? Do they like using the product? Is it safe, cost-effective, and enjoyable?

To get this information, you listen to what users say (e.g., interviews) or document how willingly they use the product (i.e., frequency of use and reuse).

Much of the information you will find about user testing (both UX testing and usability testing) will be targeted at software development (e.g., websites and online courses) and how people interact with technology (e.g., Human Computer Interaction or HCI). However, UX and usability testing can be applied to any instructional product or service, not just technology or physical products. In addition, much of the information sources for this topic focus on guidelines for designing and developing technology-enabled resources rather than how these products are evaluated. Still, design guidelines and principles can be used as specific criteria by which products might be evaluated (for example, see rules1, rules2).

When Is it appropriate to conduct user testing?

As mentioned earlier, formative evaluation should be started as soon as possible. Gathering information from users can be part of a needs analysis, a consumer review, prototype testing in the design phase, effectiveness testing in the implementation phase, but it is essential during the development phase.

Test Subjects

UX stands for user experience; as such, UX testing cannot be done without users. Both usability and UX testing gather information from users to learn how they experience a product. However, some of the evaluation data obtained in a usability study can be acquired from experts (e.g., usability heuristics analysis).

While the designer and experts will need to make some evaluative judgments, formative evaluation of an instructional product needs to get data from those who will actually be using the product. This may include those hoping to benefit from the instructional product's use (i.e., the learner) and those providing or facilitating the expected learning (e.g., teachers, parents, instructors). Both groups are considered primary stakeholders as they will be directly involved with the product's delivery and use. Therefore, both should be asked to provide information about the product's utility, effectiveness, and appeal.

The Typical User

When testing a product, you need to recruit study participants that are representative of your target audience (see video). As your intended users will be diverse, so should the group of individuals you choose to test the product. And while it may be best to select novice users (i.e., those who have never used the product), you can also gain insights from proficient users as well (i.e., those who regularly use the product or have expert knowledge).

Personas and the Intended User

Personas are fictional characters that describe your intended user. Several publically available resources exist that explain the process of developing a persona (video, resource, resource1, resource2, resource3). You may need to develop several personas as there will likely be various groups of individuals who might benefit from using your product. Each persona represents a homogeneous group of potential users with similar characteristics, behaviors, needs, and goals. Creating personas helps the designer understand users' reasons for using a product and what they need the product to do. Identifying a persona can also help select an appropriate group of people to test the product.

Sample Size (and the Rule of 5)

With the exception of a consumer review of existing products, the goal of a user test is to improve a product's design, not just to document its weaknesses. In the development phase, when a product's design is revised based on user feedback, you will want to run additional tests of the product. In each iteration, your test group need not include large numbers of people. If you have a representative sample of key informants, each test iteration can use a small testing cohort (3-5 participants, see source. video). This is called qualatative sampling. Using a limited number of users, you can often identify the majority of issues you will need to address. However, in your initial testing iterations, you may only need a single user to uncover severe flaws in the design. If this happens, you may wish to suspend testing to fix these issues before resuming your analysis with additional testers. This will definitely be the case if the issue is a safety concern. However, you may need a larger group to conduct a summative assessment of effectiveness once the product is implemented and distributed in its final form (see Sampling Basics).

Test Session Basics

Before you start testing, a few decisions you need to make include:

Moderated vs. Unmoderated - Moderated sessions allow for a back and forth discussion between the participant and facilitator. Facilitators can ask questions for clarification or dive into issues during or after the user completes tasks. The participant completes unmoderated usability sessions with no interaction from a facilitator. They are asked to explore using the product independently and report back.

As a general rule of thumb, moderated testing is more costly (i.e., facilities, time, and setup) but allows the facilitator to get detailed responses and understand the reasoning behind user behavior. Unmoderated testing is less expensive and is more authentic. However, unmoderated user sessions can provide superficial or incomplete feedback. The facilitator may need to conduct a detailed interview or have the user complete a survey once they have finished testing the product.

Remote vs. In-person – Remote testing is typically unmoderated and, as the name suggests, is done outside a structured laboratory setting in the participant’s home or workplace. Remote unmoderated testing doesn’t go as deep into a participant’s reasoning, but it allows many people to be tested in different areas using fewer resources. In-person testing is usually done in a lab setting and is typically moderated. However, an unmoderated session can be conducted in a lab setting. The evaluator may record or observe the user interacting with the product in an unmoderated session, but they analyze body language, facial expression, behavior without interacting with the user.

Gorilla Testing – is testing in the wild. Instead of recruiting a specific targeted audience, participants are approached in public places and asked to perform a quick usability test. The sessions should last no more than 10 to 15 minutes and cover only a few tasks. It is best to do gorilla testing in the early stages of the product development—when you have a tangible design (wireframes or lo-fi prototypes) and what to know whether you’re moving in the right direction. This method is beneficial for gathering quick feedback to validate assumptions, identify core usability issues, and gauge interest in the product.

Lab testing – The term laboratory may be misunderstood when describing a setting in which products are tested. Indeed, participants may be invited to a location where specialized apparatus or materials will be used (e.g., eye tracking equipment), but whenever you invite someone to test a product in an environment of your choosing, it might be considered a laboratory test. A lab setting is testing done in unique environments under specific conditions and supervised by a moderator. In contrast, field studies are defined as observations of users in their own environment as they perform their own tasks. Any time you test in a controlled setting, you run the risk of getting skewed results to some extent. Lab testing is essential; however, you will also need to test in a more authentic setting once the product is ready to implement.

Testing in a Lab vs. Field Studies Example

When testing the design of a new asynchronous online course, designers conducted several remote unmoderated evaluations of the product with a diverse group of participants from the target population. Users testing the product were given access to the course and asked to work through the material and give their impressions. One aspect of the design included external links to supplemental information. Under laboratory conditions, those testing this feature of the course indicated they loved the opportunity to search and review these optional materials. Some of the reviewers reported spending hours working through the elective content. However, summative evaluation results conducted once the product was implemented revealed that students enrolled in the course never used this feature, not once. Students working in an uncontrolled authentic setting determined that accessing this information had no impact on their grades; as a result, they didn’t. So while user testing under laboratory conditions confirmed the potential benefits of external links, testing in the classroom exposed this as an unrealized potential (i.e., a theory-to-practice issue). You cannot always control for all the confounding variables that affect actual use. (source Davies, 1999)

A few testing methods you might consider include:

Expert Evaluation (usability heuristics analysis) - Expert Evaluation (or heuristic evaluation) is different from a typical usability study in that those providing data are not typical users. Experts evaluate a product’s interface against established criteria and judge its compliance with recognized usability principles (the heuristics). Heuristic analysis is a process where experts use rules of thumb to measure the usability of a product’s design. Expert evaluation helps design teams enhance product usability early in the design and development process. Depending on the instructional product, different design principles will apply. Identifying appropriate heuristic principles can be the focus of a theory-based evaluation. (video, steps, example of website heuristics)

A/B testing - A/B testing (or A/B split testing) refers to an experimental process where people are shown two or more versions of something and asked to decide which is best. A refers to the ‘control’ or the original design. And B refers to the ‘variation’ or a new version of the design. An A/B split test takes half of your participants and presents them with version A and presents version B to the other half. You then collect data to see which works best. A/B testing is often used to optimize website performance or improve how users experience the product. (see primer, steps)

Card Sorting - Card sorting is a technique that involves asking users to organize information into logical groups. Users are given a series of labeled cards and asked to sort them into groups that they think are appropriate. It is used to figure out the best way to organize information. Often the designer is has a biased view of the organization based on their experience. Card sorting exercises can help designers figure out an organization scheme that best matches users’ mental model of potential users rather than what the designer thinks is most logical. This can also be used to organize the scope and sequence of instructional content and is an excellent method for prioritizing content. Card sorting is great for optimizing a product’s information architecture before building a prototype, lo-fi mockup, or wireframe. (see examples)

Cognitive Think-aloud Interviews – this technique goes by different names (e.g., context inquiries), but the basic technique asks test participants to perform a number of tasks while explaining what they are doing and why. This is an unmoderated testing approach where the evaluator tries to capture what users think as they perform the task without intervention. The evaluator does not interact with the user; they record the user’s actions, their explanations, and note any problems. Several publically available resources exist that cover this topic (see Intro).

Cooperative evaluation is a moderated variant of a think-aloud interview. In addition to getting the user to think aloud, the evaluator can ask the user to elaborate or consider “What if ?” situations; likewise, the user is encouraged to provide suggestions and actively criticize the product’s design. Think-aloud interviews can provide useful insights into the issues a user might have with a product. However, the value of the information provided depends on the task chosen and how well the person conducts the interview.

Before you begin, you will also need to consider the following:

Creating Scenarios

A scenario is a very short story describing a user’s need for specific information or a desire to complete a specific task. There are various types of scenarios you might create, depending on the purpose of your test. You can also ask users for their own scenarios then watch and listen as they accomplish the task. A scenario should represent a realistic and typical task the product was designed to accomplish. The facilitator should encourage users to interact with the interface on their own without guidance. Scenarios should not include any information about how to accomplish a task or give away the answer. Several publically available resources describe this process. Several publically available resources exist that cover this topic (see video explanation, resource1, resource2).

Moderator guidelines

An essential aspect of any moderated user test is the person facilitating the evaluation. An inexperienced moderator may inadvertently thwart the interview process. This can be done by failing to establish rapport, asking leading questions, failing to probe sufficiently, and neglecting to observe carefully. Usability testing can yield valuable insights, but user testing requires carefully crafted task scenarios and questions.

A few basic rules for interacting with evaluation participants include:

- Given the purpose of the test, determine the best way to conduct the test and how to interact with the participant.

- Respect the test participants’ rights and time.

- Consider the test participants as experts but remain in charge.

- Focus on the goal of the evaluation. Use carefully crafted scenarios.

- Be professional but genuine and gracious. Be open, unbiased, not offended, surprised, or overly emotional.

- Listen, let the test participants do most of the talking!

- Don’t give away information inadvertently, explain how to do a task, or ask leading questions.

- Seek to fully understand. Use probing questions effectively.

An excellent resource on this topic is provided by Molich et al. (2020) [alt link]. Several additional free resources that describe this process are available online. ( see video explanation, common mistakes)

When User Testing Fails

When deciding on which educational psychology textbook to use in a course, the instructor decided to ask several students to give their opinion. He provided them with three options and asked which would be best. This was an unmoderated remote evaluation of the textbooks using a simple A/B testing option. The student tended to agree on one textbook. When asked why, students indicated they liked the design and colors on the front of the book. Aesthetics are important—but the unmoderated format and lack of a carefully created guiding scenario resulted in a failed evaluation. The usability of the textbook should have been determined using a set of scenarios devised to evaluate the usefulness and efficiency of the design and not just the appeal. A more thorough evaluation might also have included an expert review of the content (i.e., correctness) and the design principles used.

Session overview

A typical usability test session should not last too long (less than an hour) and might include the following:

- Introduction - Make the participant comfortable, explain what will happen, and ask a few questions about the person to understand their relevant experience.

- Present the scenario(s) - Then watch and listen as they attempt to complete the task proposed in the scenario. Prompt only to gain understanding or encourage the user to explain what they are thinking or feeling. If relevant, ask participants for their own scenarios. What would they like to accomplish with the product?

- Debriefing - At the end, you can ask questions about the experience and follow up on any information provided about the product that needs further explanation. You might ask the user for suggestions or a critique of the product. If appropriate, ask the user how satisfied they are with the product’s functionality, esthetics, appeal, and desirability.

Triangulation

One last thing to remember is to trust but verify. Not everything the user says will be accurate or reasonable, and opinions about how to proceed can be diverse. Use multiple sources and look at the problem from multiple points of view. Combine multiple types of data and obtain information using several methods. Recommendations should be reasonable, ethical, plausible, and for the most part, required. Remember, not all changes can or should be done (even if deemed necessary), and not all nonessential changes should be ignored if they improve the product and are reasonable.

Chapter Summary

- Formative evaluation is typically conducted in the design phase.

- User Testing is a fundamental aspect of formative evaluation.

- By User Testing, we mean having the intended end-users test the product’s design to determine how users interact with the product.

- Both UX testing and Usability testing focus on human-centered design principles and the idea that products are designed for people to use.

- The ISO defines usability in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction.

- Formative evaluation should begin early in the design and development process.

- Typical users and subject matter experts should be used to evaluate the product.

- Personas can be developed to describe the typical intended users of a product.

- Formative evaluation test groups need not be large (Rule of 5).

- Qualitative sampling should be used to identify key informants.

- User testing can be moderated or unmoderated, remote or in-person, conducted in a laboratory setting or as a field study.

- Various types of testing can be employed, including expert evaluations (heuristic analysis), A/B testing, card sorting, and cognitive interview (context inquiries).

- The value of the information obtained from a user test depends on the task scenario used and how well the moderator conducts the interview.

- Triangulation is needed to verify data and fully understand issues.

- Recommendation for modifying a product should be reasonable, ethical, plausible, and for the most part, required.

Discussion Questions

- Consider a product you would like to evaluate. Describe the best way to test the product’s usability in terms of conducting a moderated vs. unmoderated, remote vs. in-person, and laboratory vs. field study. What would you recommend and why?

- Consider an educational product you are familiar with. Describe a persona (a user group) that typically would use this product.

References

Davies, R. (1999). Evaluation Comparison of Online and Classroom Instruction. Higher Colleges of Technology Journal. 4(1), 33-46.

Molich, R., Wilson, C., Barnum, C. M., Cooley, D., Krug, S., LaRoche, C., ... & Traynor, B. (2020). How Professionals Moderate Usability Tests. Journal of Usability Studies, 15(4).