In this chapter, we learn to relate the reaction quotient (Q) to Gibb's free energy mathematically through the expression ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q. We also learn about the relationship between the equilibrium constant (K) and ΔG°, which can be expressed through the equation ΔG° = –RTlnKeq. A negative value for ΔG indicates a spontaneous process; a positive ΔG indicates a nonspontaneous process; and a ΔG of zero indicates that the system is at equilibrium.

19.1 Free Energy and Equilibrium

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Relate standard free energy changes to equilibrium constants

The free energy change for a process may be viewed as a measure of its driving force. A negative value for ΔG represents a driving force for the process in the forward direction, while a positive value represents a driving force for the process in the reverse direction. When ΔG is zero, the forward and reverse driving forces are equal, and the process occurs in both directions at the same rate (the system is at equilibrium).

In the section on equilibrium, the reaction quotient, Q, was introduced as a convenient measure of the status of an equilibrium system. Recall that Q is the numerical value of the mass action expression for the system, and that you may use its value to identify the direction in which a reaction will proceed in order to achieve equilibrium. When Q is lesser than the equilibrium constant, K, the reaction will proceed in the forward direction until equilibrium is reached and Q = K. Conversely, if Q > K, the process will proceed in the reverse direction until equilibrium is achieved.

The free energy change for a process taking place with reactants and products present under nonstandard conditions (pressures other than 1 bar; concentrations other than 1 M) is related to the standard free energy change, according to this equation:

R is the gas constant (8.314 J/K mol), T is the kelvin or absolute temperature, and Q is the reaction quotient. This equation may be used to predict the spontaneity for a process under any given set of conditions as illustrated in Example 19.1.

Calculating ΔG under Nonstandard Conditions

What is the free energy change for the process shown here under the specified conditions?

T = 25 °C, and

Solution

The equation relating free energy change to standard free energy change and reaction quotient may be used directly:

Since the computed value for ΔG is positive, the reaction is nonspontaneous under these conditions.

Check Your Learning

Calculate the free energy change for this same reaction at 875 °C in a 5.00 L mixture containing 0.100 mol of each gas. Is the reaction spontaneous under these conditions?

For a system at equilibrium, Q = K and ΔG = 0, and the previous equation may be written as

This form of the equation provides a useful link between these two essential thermodynamic properties, and it can be used to derive equilibrium constants from standard free energy changes and vice versa. The relations between standard free energy changes and equilibrium constants are summarized in Table 19.1.

Table 19.1

Relations between Standard Free Energy Changes and Equilibrium Constants

| K | ΔG° | Composition of an Equilibrium Mixture |

|---|

| > 1 | < 0 | Products are more abundant |

| < 1 | > 0 | Reactants are more abundant |

| = 1 | = 0 | Reactants and products are comparably abundant |

Calculating an Equilibrium Constant using Standard Free Energy Change

Given that the standard free energies of formation of Ag

+(

aq), Cl

−(

aq), and AgCl(

s) are 77.1 kJ/mol, −131.2 kJ/mol, and −109.8 kJ/mol, respectively, calculate the solubility product,

Ksp, for AgCl.

Solution

The reaction of interest is the following:

The standard free energy change for this reaction is first computed using standard free energies of formation for its reactants and products:

The equilibrium constant for the reaction may then be derived from its standard free energy change:

This result is in reasonable agreement with the value provided in Appendix J.

Check Your Learning

Use the thermodynamic data provided in

Appendix G to calculate the equilibrium constant for the dissociation of dinitrogen tetroxide at 25 °C.

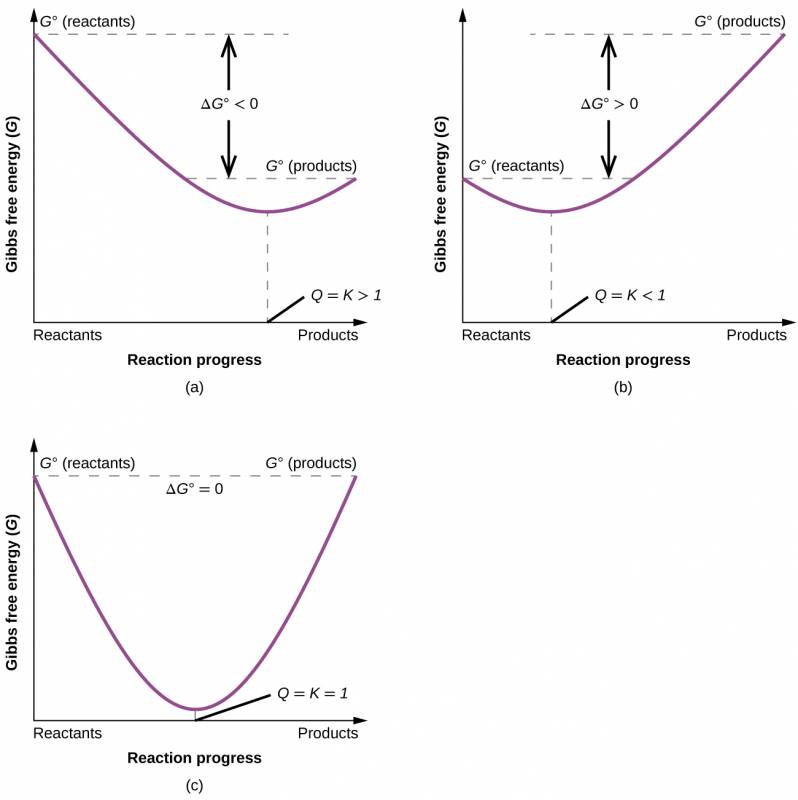

To further illustrate the relation between these two essential thermodynamic concepts, consider the observation that reactions spontaneously proceed in a direction that ultimately establishes equilibrium. As may be shown by plotting the free energy change versus the extent of the reaction (for example, as reflected in the value of Q), equilibrium is established when the system’s free energy is minimized (Figure 19.1). If a system consists of reactants and products in nonequilibrium amounts (Q ≠ K), the reaction will proceed spontaneously in the direction necessary to establish equilibrium.

Figure 19.2

These plots show the free energy versus reaction progress for systems whose standard free changes are (a) negative, (b) positive, and (c) zero. Nonequilibrium systems will proceed spontaneously in whatever direction is necessary to minimize free energy and establish equilibrium.