"Design is thinking made visual."

Saul Bass

Years ago I gave a lecture during a job interview. I chose a topic, either out of bravery or foolishness, that I had never talked about before—color theory—and I delivered it to a room of aspiring learning designers. They were courteous and engaged, but at the end, one listener raised his hand and asked the all-important question: "So what? What does any of this mean for learning designers?"

Like a poor designer, I had assumed that the answer was obvious and self-evident, but since that time I have come to realize more clearly just how rare it is for learning designers to think deeply about the visual aspects of their designs and what these decisions mean for learners. The result is that we train students, hire professionals, and lead teams in creating learning experiences without considering the choices we make with our visuals, such as layout, typography, color, etc., or if we do think about these issues as part of our design, we struggle to talk about our choices intelligently and rely instead on gut feelings of what seems good.

I have written this book for learning designers who find themselves in the position of creating visuals for learners, whether that be to help a student learn a concept, to guide an instructor in teaching a course, or to assist a website user in making a decision.

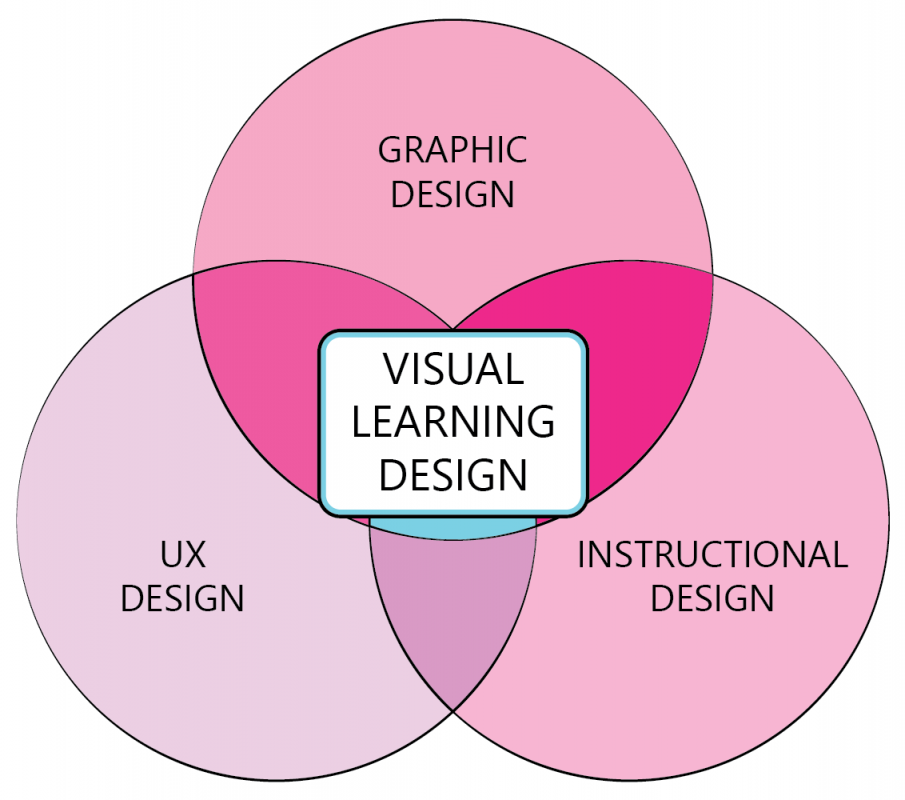

Many of us involved in learning design must draw upon various skillsets developed in different communities of professionals to do what is best for our learners. If I'm building a module in a learning management system, for instance, I'll need to know how to structure and deliver content in a manner that is pedagogically sound, while also using images and graphics in a manner supportive of my learning goals and also ensuring that each student's experience in the module is seamless from start to finish.

Figure 1

Venn Diagram of Visual Learning Design

Visual learning design draws from many fields, including graphic design, UX design, instructional design, and others

Visual learning design draws from many fields, including graphic design, UX design, instructional design, and othersThis means that to be an effective learning designer, we must straddle various professions, each with their own skills, knowledge, dispositions, and norms.

This also means that we are not only engineers or artists, but a combination of the two wherein we must mix programming, aesthetics, pedagogy, and evaluation together to form good learning experiences (Maina et al., 2015).

Thus, the good learning designer understands how people learn and how to teach them but also understands how to speak to them on a visual, emotional, technological, and behavioral level, guiding them toward learning experiences that are meaningful and rich.

In these endeavors, we are both analytic and synthetic—tearing our designs apart and creating new ones from the pieces—and the complexity of such work means that there is no comprehensive guidebook that can show us every step we should take or what works in every situation.

However, there are some overarching dispositions we should espouse, some general principles that we should follow, and some useful patterns of activity that will help us to be successful learning designers, and this book will attempt to draw your attention to some of these.

For instance, because we are focused on learning, and because learning occurs in the bodies and minds of our learners, this means that we care very deeply about our learners. We are empathetic to them, learner-centered in our approaches, and considerate of them as holistic beings (not just brains-in-vats or robots to be programmed). Because human learning is cognitive, social, and emotional, we employ design strategies and engage in practices that honor our learners as agentic and complex individuals that matter (see Anderson, 2003; Wilson, 2015). We also interact with them through our designs and data practices in ways that are ethical, inclusive, and charitable, eschewing approaches that are dehumanizing or reductionistic.

In short, we as learning designers should be obsessed with and passionate about our learners. We should love them, care about them, and want them to succeed—and we should design with their best interests at heart. This means that what we create pales in comparison to who we create it for and what their experiences with our creations will be.

Underlying principles of empathy (Tracey & Hutchinson, 2019), love (Isenbarger & Zembylas, 2006), and charity should shape our practices in important ways, such as designing to our diversity of learners (Gronseth et al., 2020, Perez, 2000), constantly evaluating our designs, responding humbly to critique, iteratively improving our designs, and so forth, and these core dispositions influence the visual aspects of our designs simply because how our learners interact with the world visually actually matters. Learner behaviors, attitudes, and emotions are shaped by what they see, and our visuals can inspire, encourage, and clarify or (alternatively) depress, frustrate, and obfuscate.

This book will attempt to highlight some of the core practices and dispositions of visual learning design while also providing resources for learners to dig more deeply into related topics. Chapters are organized into three sections: Principles, which will address theoretical issues related to visual design; Practices, which will provide concrete guidance on what to do; and Projects, which will walk the learner through scaffolded activities for improving design skills.

Chapters will also provide suggested learning activities, which may be used by students in formal classes to have meaningful learning experiences around each topic or may also be used in less-formal ways to help self-directed learners gain more from the text.

Throughout this work, my goal for you as the reader will be to grapple with what good learning design looks like—visually—and to make a plan for how you will move forward in your life and career, ever designing better and better experiences for your learners.

Learning Activity

After reading the additional readings, reflect on the following questions in a personal journal or class discussion forum:

- What does visual learning design mean to you?

- How will this shape what you create and how you create it?

Then, share your reflection with a peer and ask them to give you feedback on the following:

- What are some of the benefits of your proposed approach to visual learning design?

- What might be some problems, pitfalls, or limitations of such an approach?

Finally, respond to this feedback by reflecting on the following:

- How might you need to adjust or enact your approach to visual learning design in a way that addresses potential concerns?

References

Anderson, M. L. (2003). Embodied cognition: A field guide. Artificial Intelligence, 149(1), 91-130.

Gronseth, S. L., Michela, E., & Ugwu, L. O. (2020). Designing for diverse learners. In J. K. McDonald & R. E. West (Eds.), Design for Learning: Principles, Processes, and Praxis. EdTech Books. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/id/designing_for_diverse_learners

Isenbarger, L., & Zembylas, M. (2006). The emotional labour of caring in teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(1), 120-134.

Perez, S. A. (2000). An ethic of caring in teaching culturally diverse students. Education, 121(1).

Tracey, M. W., & Hutchinson, A. (2019). Empathic design: imagining the cognitive and emotional learner experience. Educational Technology Research and Development, 67(5), 1259-1272.

Wilson, R. A. (2015). Embodied cognition. In Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/embodied-cognition/