Student discussions are an important part of learning. Discussions allow students to be active participants in constructing knowledge and meaning of the material. In-person discussions can be energizing, with rapid exchanges where students can express both their knowledge of and feelings about a subject. These discussions can be memorable experiences that not only help students learn but also change how they relate to the course material. For instructors, it can be exciting to see students engage in meaningful discussions. However, instructors sometimes overestimate students' engagement in discussions, and whole-class discussions are often dominated by only a handful of students. In-person class discussions favor extroverts and frequently lack the voices of introverts, language learners, and others who require flexibility to reflect and form responses.

In contrast to in-person discussions, asynchronous online discussions allow for more equitable opportunities to participate. The flexibility inherent in online discussions also allows participants to be more reflective in their comments. However, most of these discussions occur using text. Text is helpful for critical thinking but can lack the communication cues that allow participants to connect with the material and other students. As a result, students can feel uninterested and isolated.

Discussions Using Asynchronous Video

In many ways asynchronous video communication can combine the best of in-person and text discussions. Similar to text-based communication, video messages are recorded and allow for high levels of flexibility and participation. Once video messages are shared, students can watch and/or respond to them immediately or when it is convenient. At the same time, they contain the fidelity and communication cues that help make in-person communication powerful.

Instructors should be aware, though, of video messaging's disadvantages. First, recording and posting messages can be uncomfortable for students initially. That said, in our research, students reported that the discomfort they felt tended to decrease significantly after just a few posts.Footnote1 Second, video messaging can be less convenient than text because you need to find a relatively quiet place to record videos and because skimming video is more difficult than skimming text. However, participants in our research tended to find that the benefits outweighed the potential drawbacks in most cases.

Using Asynchronous Video When It's the Best Option

Not all online interactions should take place using asynchronous video. The questions below will help you to determine when to use video and when to use text.

If you answer "yes" to any of these questions, then the use of asynchronous video would be beneficial:

- In part, are you assessing students' ability to speak or present on the topic?

- Are you hoping that this discussion will help establish a sense of community?

- Is it important for you to know how students feel about the topic?

- Do some students in your course have difficulty communicating in text?

If you answer "yes" to any of these questions, then the use of asynchronous text would be beneficial:

- In part, are you assessing students' ability to write on the topic?

- Are you primarily assessing students' critical thinking on the topic?

- Is a written record necessary for future review?

- Do some students in your course have difficulty communicating using video or viewing/hearing video?

It's likely that you responded "yes" to questions in both lists. When that's the case, you may want to create activities that combine text with video comments or provide students the choice of which modality they use to comment.

Types of Activities

In most cases, using a variety of discussion activities throughout a course is beneficial for students and instructors. Table 1 shows a partial list of asynchronous discussion activities.

Table 1. Asynchronous discussion activities

| Activity Type |

Description |

|

Reflections and Replies

|

A common activity in online courses is for students to read and/or view material, reflect on it, and then share their thoughts and related experiences. It's also common for instructors to require students to reply to a certain number of their peers' comments.

|

|

Round-Robin Reflections

|

Similar to reflections and replies, in round-robin reflections, students still read and/or view material, reflect on it, and then share their thoughts and related experiences. In addition, students ask a related question that they would like to know the answer to. The next person to post to the group then answers the previous person's question, shares their thoughts and related experiences, and asks a question. This continues until everyone has posted. The instructor might then choose to have the first person who posted return to and respond to the last person's question.

|

|

Debates

|

In many subject areas, debates are a common in-person classroom activity. With some preparation, these debates can also be done online with even more reflection and participation than is possible in person. Just as with in-person debates, the instructor should set the ground rules for communicating respectfully. The instructor can break down the online debate into the different phases and set deadlines for each phase. For instance, one day can be designated for opening statements. Other days could be designated for rebuttals. Lastly, students end the debate with closing statements on the last day.

|

|

Check-Ins and Updates

|

During longer projects or experiences such as practicums or internships, having students post regular updates helps instructors keep a pulse on students' progress. As a result, these updates hold students accountable for their activities even in the absence of a hard deadline. These check-ins also give students an opportunity to ask for assistance. Making these posts using video can help students maintain a sense of community.

|

|

Jigsaws

|

In a jigsaw activity, students are placed in a discussion group of about three to six students. Each student is tasked with learning a different aspect of the topic. As a result, in preparation for the discussion activity, each student is focusing on and exploring different materials. Each student then shares their learning with the rest of the group. This allows students to teach one another so that together everyone is able to form a full picture of the topic.

|

|

Peer Reviews

|

Instructors can use asynchronous video to provide feedback. Similarly, students can use video comments to provide their peers with feedback on projects. Students can share links to their project with a video comment describing their work. Students can then review the projects and provide feedback using either webcam or screencast recordings.

|

Focus on the Prompt

If a discussion you design for an in-person class flops, you can quickly adjust the activity on the fly. Although the same can be true for an online activity, making those changes mid-stream can be more difficult than in an in-person setting. As a result, instructors need to think more carefully about online discussion prompts. Although one can never be sure if a new discussion prompt will result in the desired learning outcomes, the guidelines below can help increase the likelihood of success. Many of these guidelines and the table 2 below are drawn from "Generating and Facilitating Engaging and Effective Online Discussions" (it's worth a read if you have time).

- Prompts should be open-ended and allow for multiple correct responses. Good discussion-board prompts also measure higher-order thinking skills. In many ways it's easier to write good discussion prompts that require divergent and evaluative thinking than it is to write good prompts that only require convergent thinking because you don't want the students to arrive at the same conclusion too quickly. See table 2 for examples.

- Have students discuss in small groups (four to eight students) rather than whole-class discussions.

- Set clear expectations on the length and number of posts that are required.

- Provide incentives for participation. Points should typically be given for participation. However, how those points are awarded can vary. At times you will want to use a rubric, which will allow you to assess the quality of comments. However, simply awarding points for participating is sufficient in some cases.

Table 2. Writing Good Discussion Questions (University of Oregon Teaching Effectiveness Program, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA)

|

As you prepare questions for a discussion, think about what is most important that students know and understand about the topic (the article you asked them to read, the last lecture on the topic, the chapter in the book, etc.). Shape your questions with that goal in mind. Avoid questions that prompt a yes or no answer. If you get that kind of answer, ask the student to go further and justify their response. Ask them to refer to the reading they were to do for support for their statements, ideas and opinions.

Here are some question types that stimulate different kinds of thinking:

|

| Convergent Thinking |

Divergent Thinking |

Evaluative Thinking |

|

Usually begin with:

|

Usually begin with:

- Imagine

- Suppose

- Predict...

- If..., then...

- How might...

- Can you create...

- What are some possible consequences...

|

Usually begin with these words or phrases:

- Defend

- Judge

- Justify...

- What do you think about...

- What is your opinion about...

|

|

Examples:

- How does gravity differ from electrostatic attraction?

- How was the invasion of Grenada a modern-day example of the Monroe Doctrine in action?

- Why was Richard III considered an evil king?

|

Examples:

- Suppose that Caesar never returned to Rome from Gaul. Would the Empire have existed?

- What predictions can you make regarding the voting process in Florida?

- How might life in the year 2100 differ from today?

|

Examples:

- What do you think are the advantages of solar power over coal-fired electric plants?

- Is it fair that Title IX requires colleges to fund sports for women as well as for men?

- How do you feel about raising the driving age to 18? Why?

|

Facilitating the Discussions

Something of a Goldilocks principle is at play in how much the instructor should participate in an online discussion. An instructor who participates too much can actually shut down the discussion by making the activity instructor-centered and not student-centered. However, students also require the instructor's content and pedagogical expertise. Instructor comments can motivate students to increase the quantity and quality of their comments. As a result, if the instructor participates too little, then students may not gain much from the discussion.

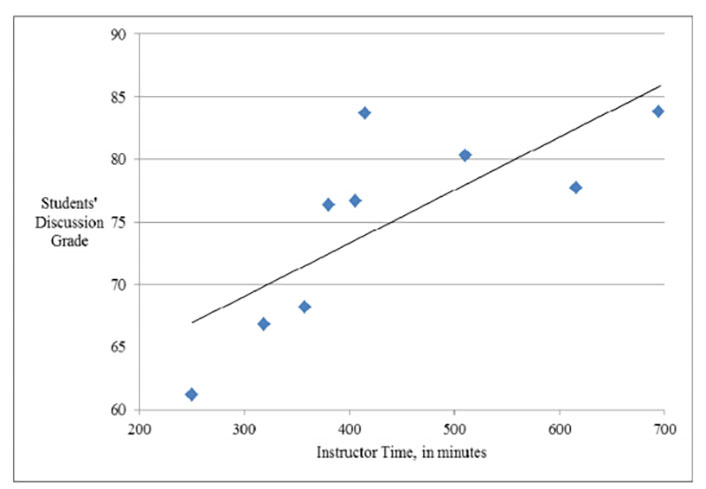

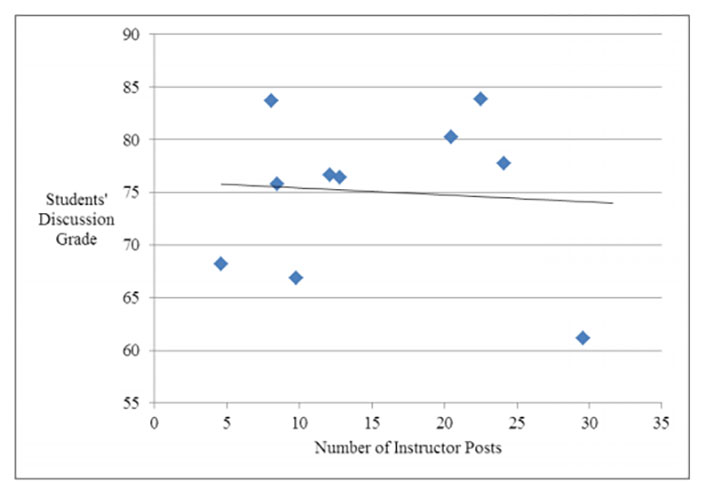

Cranney et al. conducted an interesting study examining this phenomenon by correlating student grades on discussion-based activities with the instructor's participation in those discussions.Footnote2 Specifically, two figures from their study help tell the story. Figure 1 shows a strong correlation between the amount of time that instructors spent in the online course discussion and students' grades on the discussion. However, as shown in figure 2, only a weak correlation emerged between the number of instructor posts to the discussion and student grades on the discussion activity. This indicates that it's important that instructors spend time monitoring student discussions, but they should focus more on the quality of their posts rather than on posting a lot of comments.

Figure 1. Amount of instructor time spent in online course in relation to students' overall discussion grade

Figure 1. Amount of instructor time spent in online course in relation to students' overall discussion grade

Figure 2. Number of instructor posts in the online discussion forum in relation to students' overall discussion grade

Figure 2. Number of instructor posts in the online discussion forum in relation to students' overall discussion grade

When instructors make comments they are actually fulfilling three important roles: policing, judging, and mentoring. This short video below explains each of these roles.

If you have just a few minutes, Cheryl Hayek has one of the best and most memorable answers to the question, "How many posts should the instructor make?"

Watch on YouTube

Managing Your Discussion Board

Watch on YouTube

Managing Your Discussion Board

Conclusion

Discussions are critical in helping students construct understanding. Text-based discussions can help students reflect and think critically but can lack the human touch and emotion that add meaning and interest to what's being discussed. By engaging in discussions using video recordings, students can communicate more personably while still maintaining time to reflect between exchanges. However, asynchronous video discussions still require a quality prompt and instructor facilitation.

Acknowledgment

This chapter was written with the support of EdConnect and previously published at https://edtechbooks.org/-BEc

Notes

- Jered Borup, Richard E. West, and Charles R. Graham, "Improving Online Social Presence through Asynchronous Video," The Internet and Higher Education 15, no. 3 (2012).

- Michelle Cranney, Lisa Wallace, Jeffrey L. Alexander, and Laura Alfano, "Instructor's Discussion Forum Effort: Is It Worth It?" MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching 7, no. 3 (September 2011).