INTRODUCTION

"To the young mind everything is individual, stands by itself. By and by, it finds how to join two things and see in them one nature; then three, then three thousand . . . discovering roots running underground whereby contrary and remote things cohere and flower from one stem (Emerson, 1906, n.p.)."

The concept of curriculum integration can be confusing for administrators and teachers as there are multiple definitions and models that vary from source to source. The words surrounding integration are sometimes used inconsistently and interchangeably depending on the source (Fogarty, 1991; Hall-Kenyon & Smith, 2013; Wall & Leckie, 2017). So, what is an integrated curriculum? The definition needs to remain broad because there are different types and models of integration. Drake and Burns (2004) stated that "in its simplest conception, it is about making connections" (n.p.) across disciplines. It helps learners discover the roots running between the disciplines. The depth of these connections depends on the educator's goals as they design an integrated curriculum to best meet the needs of their learners. Once a teacher identifies these goals, they can utilize the concepts behind the various models of integration to create engaging and authentic learning experiences.

MODELS OF INTEGRATION

Drake (2014) created categories for understanding the different levels of integration to help teachers make informed decisions when designing a curriculum. They include (a) multidisciplinary integration, (b) interdisciplinary integration, and (c) transdisciplinary integration. Each of these categories differs in its organizing center and is influenced by a different conception of how knowledge is best acquired. These conceptions of knowledge acquisition also impact the degree of integration (e.g., mild, moderate, intense) and the role of the discipline in the design.

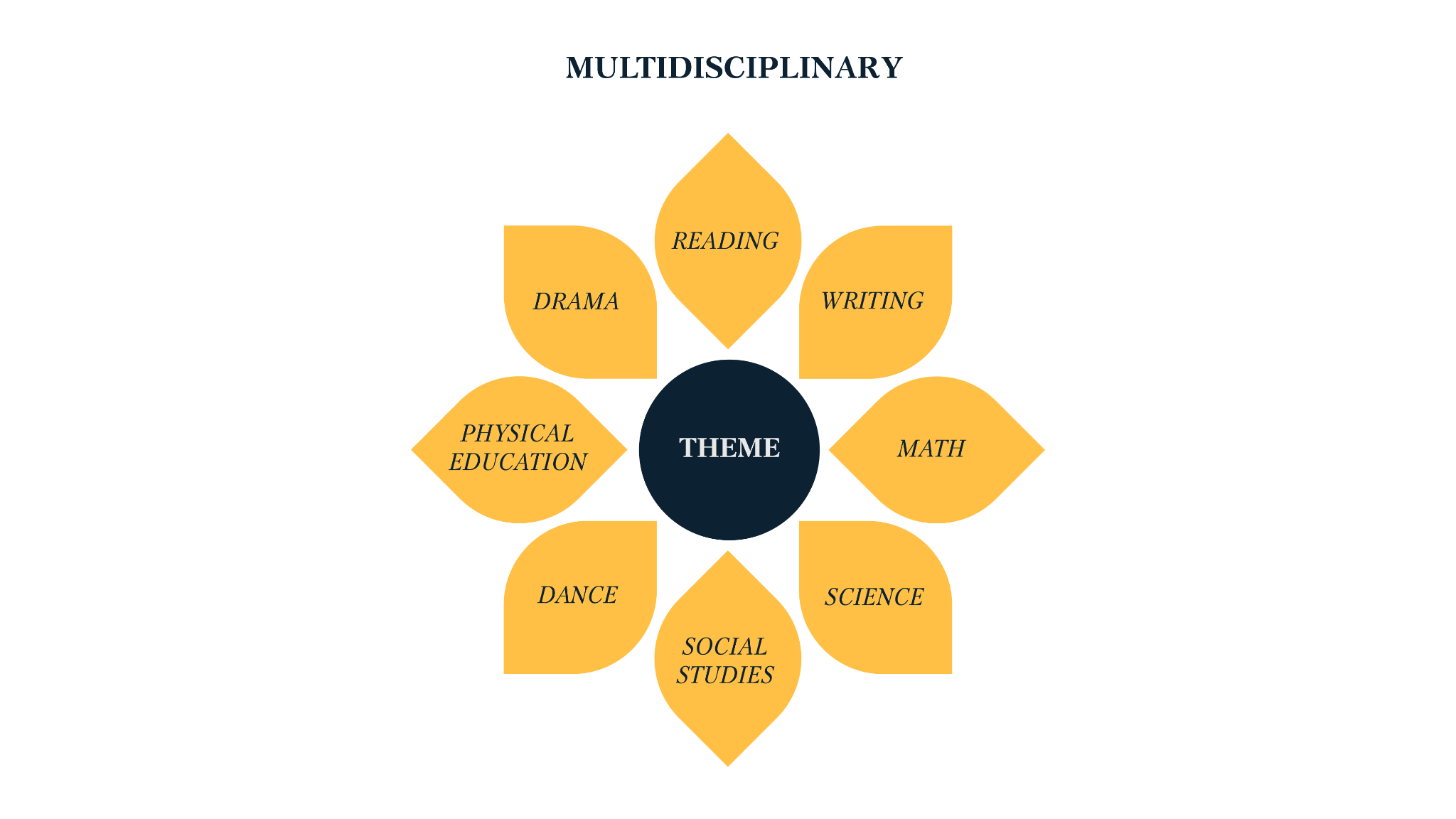

MULTIDISCIPLINARY

This mild category of integration connects with the idea that "knowledge [is] best learned through the structure of the [individual] disciplines" (Drake & Burns, n.p.) while making connections between them. In multidisciplinary integration the content areas are organized around a unifying theme but remain distinct (see Figure 1). In science, the children are engaged in scientific practices; in math, they are learning mathematical concepts; in music, they are creating, performing, or responding to compositions. However, a unifying "theme guides the selection of learning activities and texts in the multiple content areas" (Hall & Smith, 2013).

In elementary schools, this type of integration is sometimes seen when children visit different learning centers focusing on a common theme. Each learning center provides learning activities drawn from the standards of the disciplines. For example, one kindergarten teacher organized her multidisciplinary curriculum around the theme All About Me. At the math center, the students created graphs representing the number of people in their families; at the literacy center, they wrote opinion pieces about their favorite things; at the social studies center they made lists of their friends along with ways to be a good friend; and at the art center, they created self-portraits.

Multidisciplinary integration is sometimes seen in secondary schools. Students might study the universal law of gravitation in their science class, read an Isaac Newton biography in English class, and learn about the impact of the scientific revolution in history class.

Adapted from: Drake, S.M., & Burns, R.C. (2004)

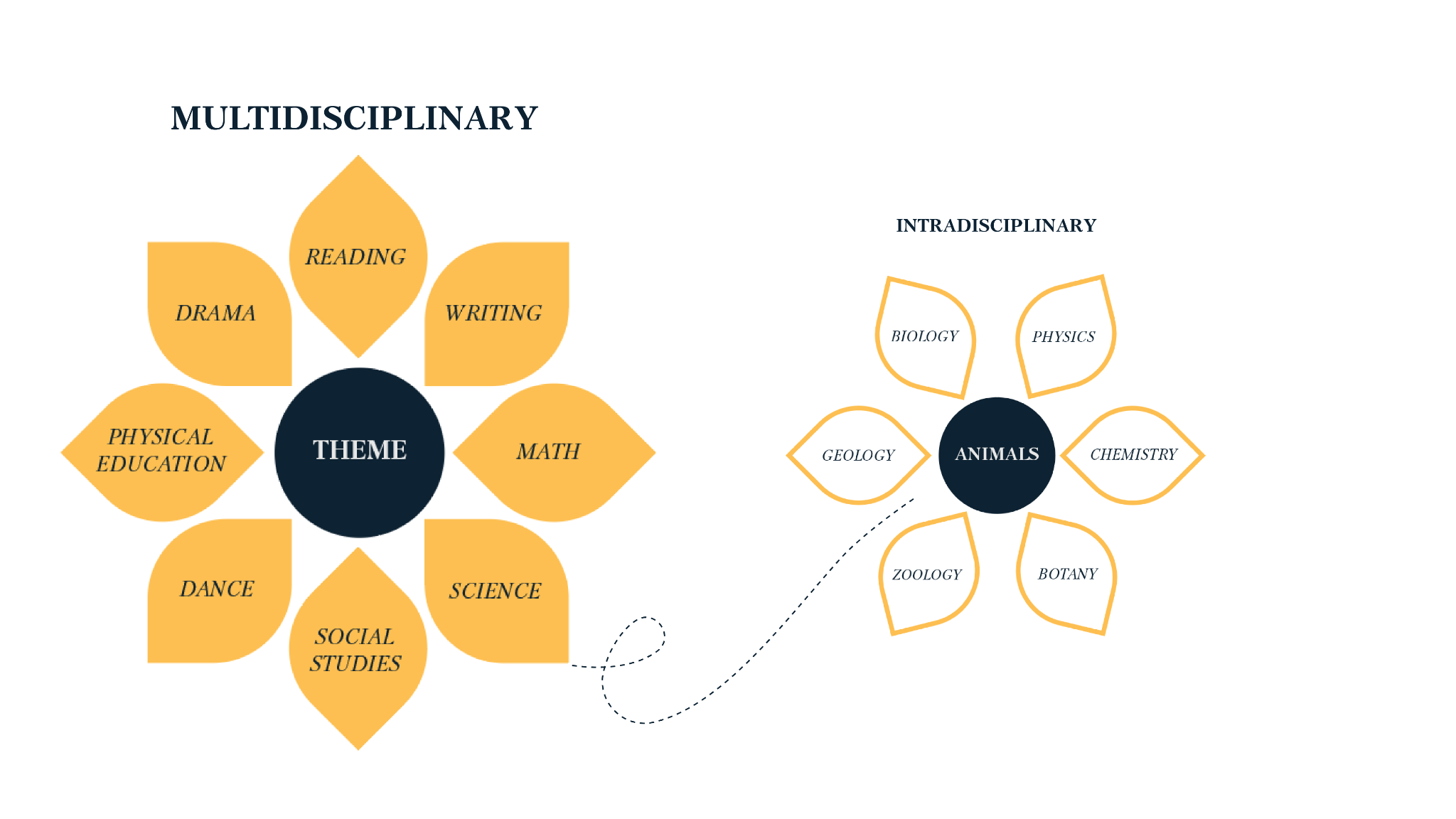

A sub-category of multidisciplinary integration is intradisciplinary integration, seen when a teacher integrates the subdisciplines of one content area around a unifying theme (see Figure 2). For example, using autumn as a theme, a teacher could create an intradisciplinary study focusing on the subdisciplines of the fine arts. In music, students could listen to Vivaldi's Autumn, identifying elements of the piece that create images of the season; in dance, they could explore movement inspired by the music. In visual arts, students could create art pieces for a fall-themed art exhibit and in drama, they could perform poems from Autumnblings (Florian, 2003) using voice to communicate meaning.

Adapted from: Drake, S.M., & Burns, R.C. (2004)

One challenge of multidisciplinary integration is maintaining the integrity of the disciplines. Themes should provide rich opportunities for authentic and rigorous learning experiences in various disciplines. Insignificant or "cute" themes should be avoided. Before creating the study, teachers should identify several core understandings surrounding the theme that will guide the development of the curriculum. For example, a study based on the theme Our Community might have the following core understandings: (a) We have responsibilities as members of a community, (b) People in our community have similarities and differences, and (c) All members of our community contribute to its success. Once the core understandings are identified, the teacher determines which disciplines best support them. If there is not an authentic connection with relevant learning standards, the content area should not be included in the study. In the above example, it may be difficult to find a relevant science connection. If that is the case, it should be omitted from the multidisciplinary model.

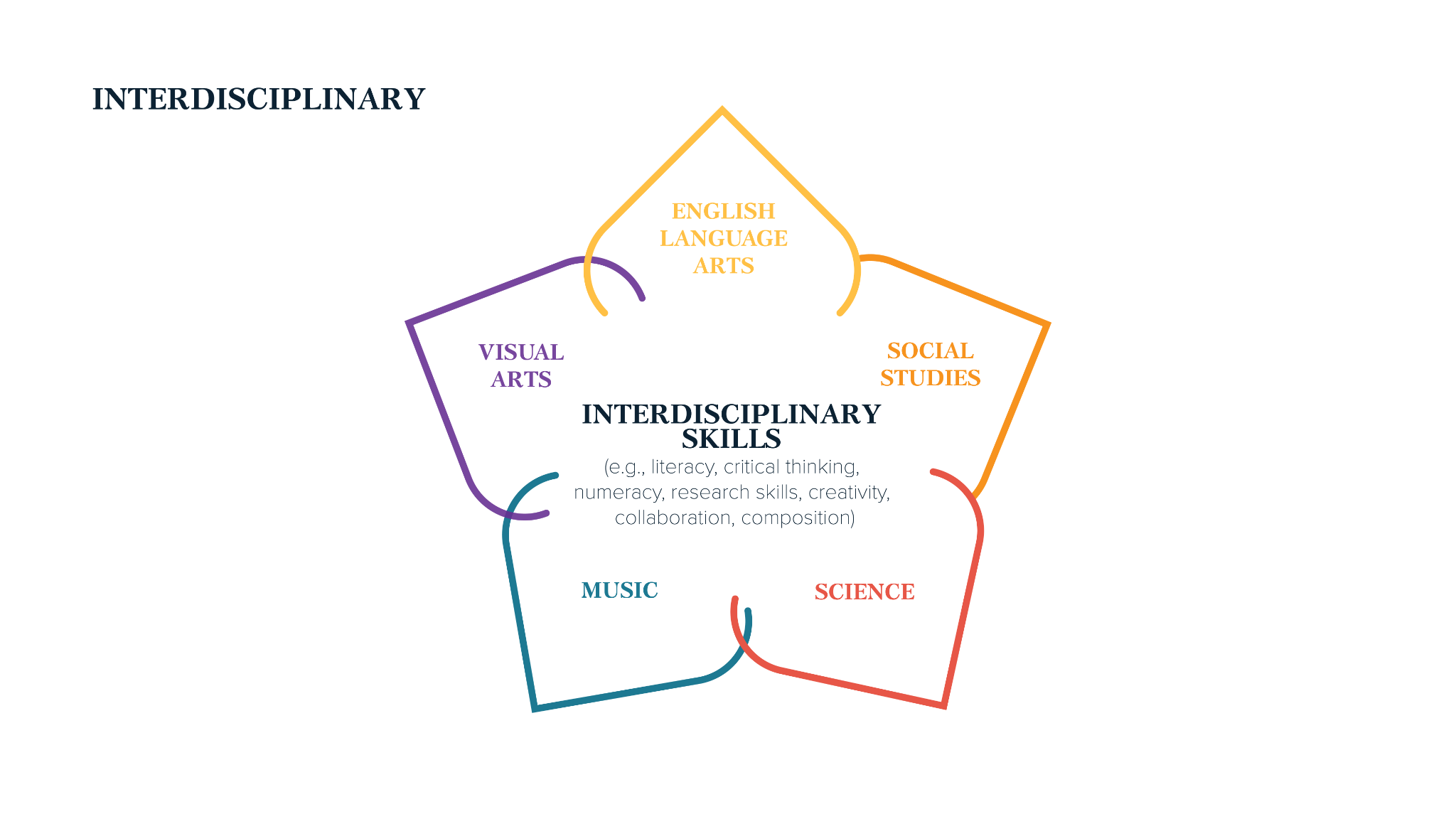

INTERDISCIPLINARY

This moderate category of integration supports the concept that "disciplines are connected by common concepts and skills" (Drake & Burns, n.p.). One of these concepts or skills becomes the organizing center of an interdisciplinary study (see Figure 3). For example, the skill of comparing and contrasting is utilized in multiple disciplines including literacy, science, social studies, mathematics, and the arts. Because it is common across disciplines, this skill might become the center of an interdisciplinary study. In literacy, students could learn the vocabulary used in compare/contrast texts (i.e., similar, different, alike, in comparison, in common, in contrast); in science, they could use the vocabulary to record their scientific observations; in drama, they could describe the similarities and differences between two versions of the same scene. The skill is intentionally taught, reinforced, and assessed within the context of each discipline (Hall & Smith, 2013). Again, teachers should only make authentic curriculum connections. If a skill or concept is not an element of a discipline, that content area should not be included in an interdisciplinary integration model.

Adapted from: Drake, S.M., & Burns, R.C. (2004)

TRANSDISCIPLINARY

This intense category of integration is based on the concept that "all knowledge is interconnected and interdependent" (Drake & Burns, 2013, n.p.). The organizing center is a real-life problem or context and/or student questions (see Figure 4) that emerge from students rather than the teacher. The disciplines utilized may be identified, but the focus is on solving the problem and/or answering the questions. In transdisciplinary integration, the teacher plays the role of co-learner and co-planner. These studies can be long- or short-term as the length is dedicated by interest of the students and almost always include on-site research work outside of the classroom.

One way a teacher could implement a transdisciplinary study is by using project- or problem-based learning where students seek to find solutions to a relevant issue. Projects can be long-term or short-term depending on the problem or questions. Katz (2014) and Drake and Burns (2004) suggest using the following three phases for project-based learning:

- Phase 1 - "Teachers and students select a topic of study based on student interests, curriculum standards, and local resources" (Drake & Burn, 2004, n.p.).

- Phase 2 - Teachers access students' prior knowledge and experience and assist them in generating questions that will lead to exploration and new understandings.

- Phase 3 - "[S]tudents share their work with others in a culminating activity . . . [and] display the results of their exploration" (Drake & Burns, 2004, n.p.), review the learning experience, and assess their new understandings.

After her students found a wasp's nest under the slide on the playground, one kindergarten teacher designed a project based on her students' questions about animals that build nests. The students drew pictures of animal nests they previously experienced in their local environment and generated a list of questions to guide their explorations. The teacher invited an entomologist to visit the classroom to explain how wasps build their nests, provided books and websites with information about animal nests, and arranged a field visit to a local museum with a large collection of nests. While at the museum, the students made observational drawings of the animals and their nests, used string to measure the size of the nests, and interviewed museum docents. For their culminating activity, the students each created an animal nest using natural and synthetic materials. They also drew a picture of their animal accompanied by a short informational text. Using their nests, pictures, and texts as exhibits, they created a classroom museum inviting peers and families to visit. The teacher documented their learning journey using photographs, artifacts, and narratives displayed on a classroom wall. Though the focus of this project was answering their questions about nest-building animals, students did meet standards in multiple disciplines including science, literacy, mathematics, and visual arts.

Adapted from: Drake, S.M., & Burns, R.C. (2004)

CONCLUSION

Though significant differences exist between the different types of integration, they should share the following common characteristics (California Connect, n.d.):

- Academic rigor - Design studies to address identified learning standards.

- Authenticity - Use real-world contexts (i.e., home, school, community).

- Active Exploration - Include learning activities that promote active construction of knowledge.

As teachers attend to each of these characteristics as they design integrated studies, children's engagement and learning will increase as they discover "roots running underground whereby contrary and remote things cohere and flower from one stem" (Emerson, 1904, n.p).

REFERENCES

Connect California (n.d.). What is multidisciplinary integrated curriculum? Retrieved from: https://connectednational.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/LL_What_is_Multidisciplinary_Integrated_Curriculum_v2.pdf.

Drake, S. M. (2012). Creating standards-based integrated curriculum. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Drake, S.M., & Burns, R.C. (2004). Meeting standards through integrated curriculum. Retrieved from: http://www.ascd.org/Publications/Books/Overview/Meeting-Standards-Through-Integrated-Curriculum.aspx.

Emerson, R.W. (1906). The American scholar. In W. J. Bryan and F. W. Halsey’s (Eds.) The World’s Famous Orations (1781-1837). Retrieved from: https://www.age-of-the-sage.org/transcendentalism/emerson/american_scholar.html.

Florian, D. (2003). Autumnblings. New York, NY: Greenwillow.

Fogarty, R. (1991). Ten ways to integrate curriculum. Educational Leadership, 49(2), 61-65.

Hall-Kenyon, K., & Smith, L.K. 2013). Negotiating a shared definition of curriculum integration: A self-study of two teacher educators from different disciplines, Teacher Education Quarterly, (40)2, 89-108.

Wall, A., & Leckie, A. (2017). Curriculum integration: An overview, Current Issues in Middle Level Education 22(1), 36-40.