Learner agency plays a key role in self-determined learning (heutagogy) since, in heutagogy, the learner becomes fully responsible for the whole learning experience. Learner agency is further increased in online learning environments because learners require a great deal of self-regulation. Self-regulation and self-directedness are crucial aspects of learner agency and heutagogy: learner agency is perceived as learners’ lurking potential for self-directed engagement. Learner agency emerges from the interaction of several factors such as self-concept, beliefs, motivation, affect, self-regulation and self-efficacy. Learner agency in general, and in the literature of heutagogy as well, is often studied within a qualitative framework, and research carried out with quantitative measures on attributes that contribute to learner agency is scarce. Our study’s focus was to understand which attributes among self-efficacy, self-reflection and insight, and internet skills were statistically significant contributors to self-directed learning readiness of Language MOOC learners. Our findings highlighted that insight and self-efficacy were the most important predictors of learners’ readiness for self-directed learning. As a result of this study, we propose a framework based on the empirical findings and the theory of heutagogy to help educational designers and course owners enhance learners’ self-directed and self-determined learning attributes.

Introduction: MOOCs as heutagogical in essence

In an era when it is explicitly assumed that learning is no longer limited to the years of formal schooling but is envisaged as a lifelong process, massive open online courses (MOOCs) promised to fulfil (at least part of) the educational need of our postmodern society. Indeed, MOOCs are offering unrestrictive and unselective educational opportunities to learners worldwide. Online education has existed for many years globally as education institutions and private providers have tried to find ways to expand their markets. However, MOOCs brought in high-quality content from many prestigious institutions of higher education and structured the content into a course format through third-party providers such as Coursera, edX, Udacity, and FutureLearn, among others (Baggaley, 2013; Pappano, 2012).

Despite MOOCs claiming to be “democratisers of education”, they seem to have failed to achieve that role so far (Reich & Ruipérez-Valiente 2019). The identification of the source of that failure remains a crucial issue, though researchers have argued that one of the reasons can be lack of skills (Beaven et al., 2014; Khalil & Ebner, 2014). MOOCs are different from other e-learning resources because of their massive and open nature (Terras & Ramsay, 2015). The learning situations based on MOOCs make more apparent the mediation role (in Vygotskian terms) (Vygotsky, 1986) of the resources used by learners. In the absence of the trainer/teacher, the learner’s locus of control clearly shifts from the provider (the trainer/teacher) to themselves, thereby creating the need for their awareness of power and control over their learning so they become fully responsible for their own learning. If learners do not possess the relevant skills and do not become active agents of the learning experience to face such a shift that MOOCs represent, MOOCs will not be “open” to them (Terras & Ramsay, 2015).

According to Glassner and Back (2020), heutagogy is introduced when the intention is to empower people to become autonomous agents as learners, to motivate and stimulate learners to learn in a meaningful way and to help to bridge the gap between the hyperconnected social world and formal education. The fundamental and crucial idea is that, provided the proper environment, people could learn and be self-determined (Hase & Kenyon, 2007). Interestingly, most of the literature focusing on independent and autonomous learning in MOOCs employs the concepts of self-directed and/or self-regulated learning. Although, Terras and Ramsay (2015) have a different perspective, and they advocate that a heutagogical perspective is necessary to understand MOOC learners’ psychological characteristics and that 'a heutagogical approach is well suited to MOOCs as it supports learners-generated content and self-direction in terms of learning path and information discovery' (p.480).

The MOOC structure is intentionally pre-defined, putting the responsibility on the learner as an adaptive organism. Therefore, an active role for the learner is highly relevant for learning in MOOCs. Pegrum (2009) calls for the development of participatory literacy, which is closely linked to the creation and sharing of user-generated content: although, the concept of participation per se entails more than creating and sharing. One must note that skill or competent action is not grounded in individual accumulation of knowledge. Instead, agency is defined in the context of action, and it is generated in the web of social relations and human artefacts that define the context of action. At the same time, engagement affords the power (and provides conditions) to shape the context in which the learner can construct and experience an identity of competence. Competence is a necessary ability for a learner to act effectively and efficiently to cope with tasks and problems. Connecting competence to the idea of an ’ability to act’ echoes the structuring concept of capability and implies that the learner has legitimacy to act. Research suggests that, “a major problem with MOOCs is the lack of sustained engagement” (Terras & Ramsay, 2015, p. 477) and, therefore, claims that the burden of regulating and structuring learning is carried mostly by the student rather than by the instructor. This again calls for increased responsibility of the learner for engagement and participation, bringing in the associated need for certain competencies or skills.

Two fundamental ideas constitute the rationale to claim a heutagogical perspective when addressing MOOC-based learning. Firstly, the variability of learning profiles of MOOC attendants makes it impossible to accommodate the format, content, and rhythm to a one-size-fits-all model, then transposing a large part of responsibility of adaptation to the learner. Secondly, the flexibility affordances of a heutagogical approach faces the issue of conquering the learner and creating conditions for their very personal and individual engagement in action. This learner-driven approach seems particularly applicable to MOOCs, knowing that the variability of learners’ profiles is perhaps the widest, which is the most complex challenge faced by MOOC designers. A heutagogical approach affords the necessary expansive flexibility required to support a student body whose motivations for engagement are largely uncharted. Moreover, Terras and Ramsay (2015) argue that the heutagogical approach 'supports the detailed consideration of individual learners’ psychological attributes, skills and preferences and thereby highlights the importance of considering the psychological constructs that explain learner behaviour' (p.483), which is essential to effective MOOC design.

In this chapter, we focus on the implications of applying a heutagogical perspective on a Language MOOC (LMOOC) learning environment and gaining insight into the psychological profile of LMOOC learners from a heutagogical perspective.

Implications of heutagogy for foreign language acquisition and teaching

The literature on foreign language learning and teaching using a heutagogical approach is extremely scarce. We found no studies, neither theoretical nor empirical, that employed heutagogy in a foreign language learning environment. This scarcity can be understood and explained through some interesting facts about the status of the two research fields.

On the one hand, heutagogy has been strongly and recently linked to distance education and online learning, as well as to the online environment and digital technologies. On the other hand, the role and application of information and communication technologies in language learning – the so-called computer assisted language learning (CALL) – is a relatively new area for language learners, teachers and scholars (Tafazoli & Golshan, 2014; Zhou, 2018). However, CALL research has been rapidly evolving. Soon after the rise of MOOCs, a separate subfield of research has emerged, namely Language MOOCs (LMOOCs) (Bárcena & Martín-Monje, 2014), which increases the need and interest to understand better the potential and implications of heutagogy in foreign language learning in online environments.

Heutagogy has potential for foreign language learning, especially in the globalized 21st-century social world where communicating in a foreign language permeates most economic and work contexts. In the current globalized world, where low-cost airline companies make travelling more affordable and the world wide web makes international connections easier, speaking foreign languages is already a prerequisite for success. Acquiring a foreign language is no longer a luxury: it has long become a necessity. Although the need for acquiring foreign languages has increased, the time available for learning has been continuously diminishing. Language learners need to acquire language skills faster and often work through autonomous learning approaches. They unwittingly become responsible for acquiring the language due to social (and often professional) pressure and hence they become very active agents of their learning experiences. Moreover, existing language learning applications, LMOOCs and direct exposure to authentic materials[1] through the web not only contribute but also induce learners to have more agency in the foreign language acquisition process. The importance of learner agency in language learning has been recognised by sociocultural theorists (Xiao, 2014), that is, learners indeed are actively seeking linguistic competence and non-linguistic outcomes instead of waiting passively to be taught.

Today’s language learners’ needs point mainly to communication skills, which is also accompanied by today’s trend of communicative language teaching (CLT) and by the existing frameworks for language acquisition, for example, the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). The collective aim is to be able to communicate efficiently as soon as possible. Being exposed to and exposing learners to authentic materials and contexts highly contribute to (communicative) language skill acquisition.

Noted language theorists have proposed that there are two separate actions while learning a language: spontaneous and studied (Krashen, 1985; Nation, 2001; Palmer, 1921). According to Palmer (1921), spontaneous language abilities are those that are acquired subconsciously and lead to more natural spoken language. Krashen (1985) claims that the subconsciously acquired language skills are easily used in conversation. Oppositely, studied and learned language skills that are acquired in academic settings where the emphasis usually is on structured grammar and vocabulary are more difficult to access and recall in spontaneous conversations (Pagnotta, 2016). For this reason, spontaneous language use and learning are essential for today’s language learners who seek to successfully communicate in every situation. But how does the spontaneity of language learning relate to heutagogy, and how and why can a heutagogical approach to language learning be beneficial?

One of heutagogy’s central principles is capability. Capability is one's ability to use the acquired skills and competencies in both new and familiar situations (Hase & Tay, 2004). In an online or technology-mediated language learning context, capability development can only occur in authentic environments. Learners acquire certain language skills mostly in a (semi) formal environment such as an online course or application, which becomes the well-known context of language use for them. To develop capability, learners need to apply the acquired skills in novel situations, which, in this case, emerge mainly in an authentic environment. Using the language outside of the formal learning environment contributes to spontaneous language learning, which as we have argued above, will then contribute to a more natural spoken language (communication). Learners subconsciously and informally acquire new knowledge in the authentic environment, which potentially leads to a more fluid spontaneous conversation.

Self-determined learning (heutagogy) can boost online language learning, because when adult learners have the opportunity to self-reflect and create their own study plan, the experience has a positive impact on their motivation and performance in the target language (Fengning, 2012; Christophersen, Elstad and Turmo, 2011). Heutagogy gives enough freedom to online learners to plan their own learning trajectories and prepare their own, personal study plans. Double- and triple-loop learning (metacognition) allow the learner to have a deeper insight into their learning needs and to create adequate study plans to achieve their learning objectives.

As we have seen, applying a heutagogical approach can be beneficial in both contexts: MOOCs and foreign language learning. Intending to dig deeper in this topic, we conducted a study in an LMOOC environment. We aimed to map the psychosocial and cognitive profile of learners by applying heutagogical attributes to discover which attributes are the most influential to learners’ self-directed learning readiness. We also wanted to understand LMOOC learners’ linguistic competencies, their language learning preferences, and gain insight into their capability development. The final output of the research was a framework for designing LMOOCs that considered both learners’ psychosocial and cognitive profile as well as their language learning preferences.

LMOOC learners psychosocial and cognitive profile and their language learning preferences: A mixed methods correlational study

We conducted a mixed methods study where five heutagogical attributes – namely self-directed learning readiness, self-efficacy, self-reflection and insight, and five internet skills – were measured and the most influential skills were determined through statistical analysis. Qualitative data was collected on learners’ preferred language activity types and their capability development (i.e., on their language use outside of the course context). The study was carried out between September 2018 and April 2019 in two separate Italian language MOOCs provided by Wellesley College on the edX platform (www.edx.org). Quantitative and qualitative questionnaires were administered separately. The quantitative survey resulted in 1140 valid answers from a total of 1849 administered questionnaires. For the open-ended questions, we obtained 147 answers to one question and 138 for a second. The detailed description of the research and results are published elsewhere for the interested reader (Agonács et al., 2019, 2020). Here, we present a summary of our main findings.

Our first observation was that, based on measures of a combined skill set, most of the participants fell into the moderate and low self-determined learners’ groups. Only a tiny portion (a little more than 4% of the valid sample) was found to be highly self-determined. Moreover, our results confirmed that “self-efficacy is the very foundation of human agency” (Xiao, 2014, p. 5) since it was found to be the most influential variable of self-directed learning readiness.

We also understood that insight is a strong influencing variable and consistent through the three groups. Self-directedness, indeed, implicates metacognition. When learners are aware of their progress in language learning, they become confident and develop a strong sense of self-efficacy (Xiao, 2014). Both confidence and self-efficacy are the pillars of capability development. For learners to become aware of their own progress, there is a need for metacognition. However, surprisingly, according to our results, the clarity of one's knowledge about him or herself (i.e. insight) is more important than the process of or engagement in self-reflecting. The proactive approach to learning (monitoring, reflecting, acting) is important, and learners do need to reflect on the learning experience continuously. However, if they do not clearly understand the progress they make and which areas are needed strengthening, the reflective process itself does not seem to have a very significant impact on their readiness for self-directed learning.

As for the qualitative string of the study, we understood that learners prefer and engage more in receptive activities than productive or interactive activities. We observed this tendency also in cases when the learner’s learning objective was to be able to produce the language. Moreover, for learners, activities directly related to linguistic (grammatical and lexical) competencies have great importance in language acquisition. Therefore, we observed a dissonance – clearly outlined in learners’ reflections – between their need for communicative competences (speaking) and their preference for receptive activity types.

Based on our main findings, we outlined some important suggestions that can help MOOC designers and providers in how to help learners go through a learning journey in an LMOOC successfully; how to enhance their skill set and help them become self-determined learners and to prepare them for a more communicative language learning approach.

Framework for LMOOCs based on heutagogical principles and our empirical results

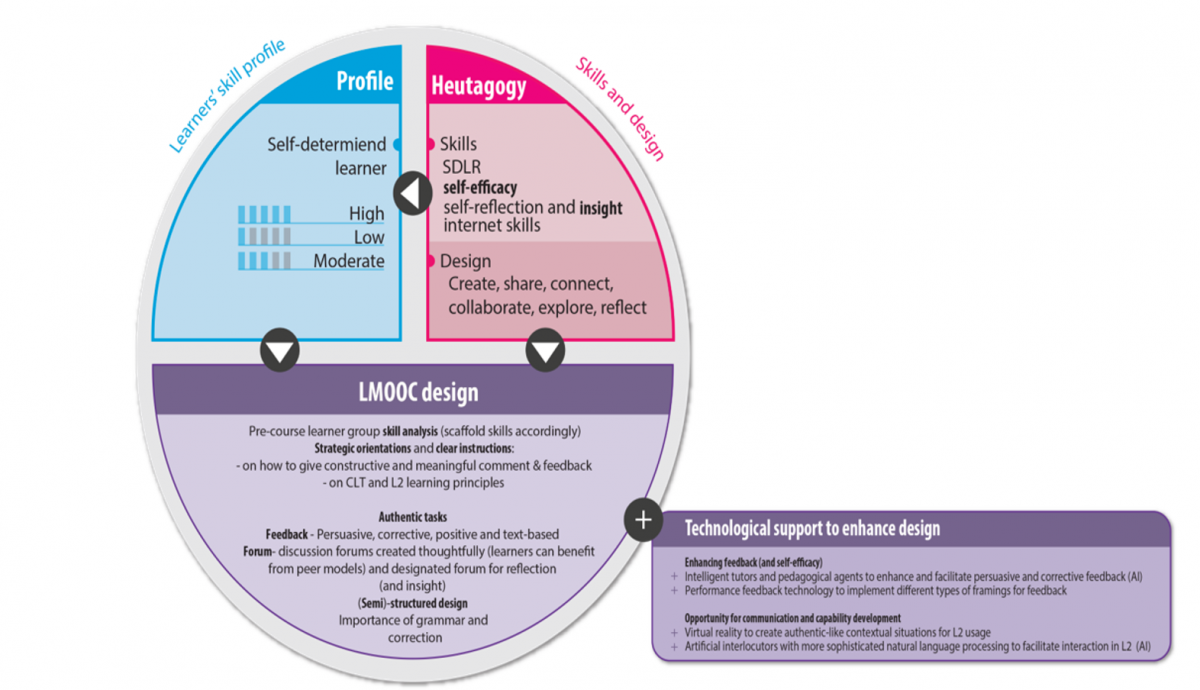

The main findings of our study revealed that most LMOOC learners not only lack self-determined skills but also have a preference for a more structured and more traditional way of learning a foreign language. As outlined above, most of the currently existing (L)MOOCs focus mainly on the delivery of content and are not designed to enhance learners’ skill profile. Because MOOCs are heutagogical in their nature, the LMOOC design should be driven by the design elements of heutagogy (create, share, connect, explore, collaborate, reflect) and learners’ psychosocial and cognitive profile should also be considered. From the other hand, learners’ language learning preference for a more traditional and structured model should not be ignored either, when designing LMOOCs (see Figure 1). Enhancing learners’ skills profile will likely contribute to stronger heutagogical (self-determined) learning, which could possibly have a significant impact on retention and engagement in MOOCs. (The conceptual framework and design suggestions are summarized in Figure 1.)

How to enhance self-efficacy

In order to help learners engage more in communicative language activities, clear orientations should be given on CLT, and instructors may have to help students understand some empirically proven principles of L2 (as suggested by Brown, 2009). Clear instructions should also be given on how to interact (e.g., types of comments and feedback that are beneficial in the forum activity or peer-to-peer review). The question of strategic orientation of learners should be taken seriously because clear orientation can improve learners’ self-efficacy (as hinted by Hodges, 2016).

Figure 1

Conceptual framework and design suggestions

Moreover, for learners, feedback does have importance. Feedback options in a massive environment are currently quite limited to simple automatic (frequently yes and no) answers. Corrective feedback is essential not only because learners can gain confidence (which is necessary for capability development), but also because persuasive feedback can enhance positive self-efficacy (Hodges, 2016).

How to enhance insight

It is interesting, though is understandable from a theoretical point of view, that insight (but not engagement in or motivation for self-reflection) is an influencing factor for self-directed and self-determined learning. Insight means that learners have a clear understanding of their thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. Roberts and Stark (2008) have already called attention to the fact that the self-reflection process itself does not necessarily lead to insight. Therefore, even if learners are motivated to reflect, and they do engage in a reflective process, may not gain insight. For that reason, it is crucial to guide and help learners how to reflect efficiently. Developing insight of learners in a MOOC can be challenging, though can be viable through providing a designated space where they can share their strategies, difficulties, and successes that encounter during the learning and reflecting process and get persuasive and constructive feedback from a specialised tutor.

How to alleviate the dissonance between learner's preferences for a more traditional approach and their actual needs pointing to communicative language competencies

Learners' learning preferences need to be understood, and design should be developed accordingly. It is important to enhance LMOOC learners’ engagement in productive and interactive activities (such as forums, speaking or writing activities); however, during design it has to be kept in mind that learners still have a preference for activities that teach the formal structure of the language. For that reason, a coherent and consistent structure is an important design aspect for LMOOCs. Though “language is about communication, and there is nothing more motivating than being able to use one's newly acquired language skills in an authentic environment” (Perifanou, 2014, para. 23). As mentioned above, authentic environments are good for spontaneous language learning and use. For that reason, the opportunity for language use in authentic environments should be provided, and language use should be encouraged to further enhance learners’ communicative language skills. Foreign language use in authentic environments is extremely important not only for enhancing communicative language competencies but also because it contributes to capability development.

What the future holds for online education

The landscape of online education is rapidly changing. In many cultures, the pressure of everyday life has made it clear that the two variables, space and time, have taken priority in learners’ decisions regarding training and education.

From the learner’s point of view, space and time for training started to be questioned, as learners realised the benefits of their time flexibility when taking courses online and became aware of the fact that online social presence brings new dimensions to the traditional face-to-face training format. The current confinement rules in place in most countries, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, shows how people are able to adapt and organise their time to run online activities (both in work practices as well as for leisure), escaping the need for displacement and therefore dealing with the frozen variable of space in rather creative forms. People have recently become more interested in online learning. Christof Rindlisbacher (2020) affirms that Google queries for “online classes” increased a whopping 204% from March 7 to March 21 in 2020 according to Google Trends, while queries for “online education” increased 90%. Dhawal Shah (2020) (CEO of Class Central) also called attention to the fact that EdX climbed into the top 1000 websites in the world, thereby joining Coursera.

From the point of view of the trainer/teacher, a learner-centred approach is transformative regarding the aims of training/teaching ,as the focus is no longer on transmitting information but rather on promoting learning how to learn. This makes the task of teachers much more difficult as it goes into just “let the learner learn” and the task of designers to offer learning experiences that address the needs of a great variety of learners.

The question is whether this is a temporary effect, which will decrease after the pandemic, or if it is something that will definitively and irreversibly change the educational landscape. It is still early to have an answer to that question, and only statistically calculated previsions could be given right now. But one thing is certain: now more than ever, people need refined self-determined learning skills to upskill and reskill and prepare themselves for the upcoming changes – on personal, professional, economic and political levels – that this pandemic will and has already brought to the world. Only the future will tell us if we – educators, MOOC designers, and researchers – have are up to the task of helping large masses of learners acquire the necessary skills for successful autonomous online learning.

References

Agonács, N., Matos, J. F., Bartalesi-Graf, D., & O’Steen, D. N. (2019). On the path to self-determined learning: a mixed methods study of learners’ attributes and strategies to learn in language MOOCs. International Journal of Learning Technology, 14(4), 304–330. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLT.2019.106553

Agonács, N., Matos, J. F., Bartalesi-Graf, D., & O’Steen, D. N. (2020). Are you ready? Self-determined learning readiness of language MOOC learners. Education and Information Technologies, 25(2), 1161–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10017-1

Baggaley, J. (2013). MOOC rampant. Distance Education, 34(3), 368–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835768

Bárcena, E., & Martín-Monje, E. (2014). Introduction. Language MOOCs: An emerging field. In E. Bárcena & E. Martín-Monje (Eds.), Language MOOCs: Providing Learning, Transcending Boundaries (pp. 1–15). De Gruyter Open Ltd.

Beaven, T., Hauck, M., Comas-Quinn, A., Lewis, T., & de los Arcos, B. (2014). MOOCs: Striking the right balance between facilitation and self-determination. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 31–43. http://jolt.merlot.org/vol10no1/beaven_0314.pdf

Brown, A. V. (2009). Students’ and teachers’ perceptions of effective foreign language teaching: A comparison of ideals. Modern Language Journal, 93(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00827.x

Christophersen, K., Elstad, E., & Turmo, A. (2011). Contextual determinants of school teaching intensity in the teaching of adult immigrant students. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education, 17(1), 3–22. https://doi:10.7227/jace.17.1.3

Fengning, D. (2012). Using study plans to develop self-directed learning skills: Implications from a pilot project. College Student Journal, 1(46), 223–232.

Glassner, A., & Back, S. (2020). Exploring heutagogy in higher education. Academia meets the Zeitgeist. Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

Hase, S., & Hou Tay, B. (2004). Capability for complex systems: beyond competence. Proceedings of Systems Engineering / Test and Evaluation Conference, SETE 2004, Focusing on Project Success.

Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2007). Heutagogy: A child of complexity theory. Complicity: An International Journal of Complexity and Education, 4(1), 111–118. https://doi:10.29173/cmplct8766

Hodges, C. B. (2016). The development of learner self-efficacy in MOOCs. Proceedings of the 2016 GlobalLearn Conference.

Khalil, H., & Ebner, M. (2014). MOOCs completion rates and possible methods to improve retention - A literature review. Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2014, 1236–1244.

Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. Longman.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

Pagnotta, J. (2016). An examination of how adult English Second Language learners learn pronunciation skills [Doctorate dissertation]. George Fox University.

Palmer, H. E. (1921). The principles of language study. World Book Company.

Pappano, L. (2012, November 2). The year of the MOOC. The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html

Pegrum, M. (2009). From blogs to bombs. The future of digital technologies in education. UWA Publishing. http://uwap.uwa.edu.au/static/files/assets/d7e7fbb8/From_Blogs_to_Bombs_Extract.pdf

Perifanou, M. A. (2014). PLEs & MOOCs in language learning context: A challenging connection. 5th International Conference on Personal Learning Environments, 16th-18th July, Tallina.

Reich, J., & Ruipérez-Valiente, J. A. (2019). The MOOC pivot. Science Education, 363(6423), 130–131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav7958.

Rindlisbacher, C. (2020, March 24). Surging interest in online education [Blog post]. https://www.classcentral.com/report/surging-interest-in-online-education/

Roberts, C., & Stark, P. (2008). Readiness for self-directed change in professional behaviours: Factorial validation of the Self-Reflection and Insight Scale. Medical Education, 42(11), 1054–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03156.x

Shah, D. (2020, April 6). EdX Breaks Into World’s Top-1000 Websites [Blog post]. Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://www.classcentral.com/report/edx-top-1000-website/

Tafazoli, D., & Golshan, N. (2014). Review of computer-assisted language learning: History, merits & barriers. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 2(5–1), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijll.s.2014020501.15

Terras, M. M., & Ramsay, J. (2015). Massive open online courses (MOOCs): Insights and challenges from a psychological perspective. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 472–487. https://edtechbooks.org/-ecNK

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. Alex Kozulin (ed.), The MIT Press

Xiao, J. (2014). Learner agency in language learning: The story of a distance learner of EFL in China. Distance Education, 35(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2014.891429

Zhou, Z. (2018). Second language learning in the technology-mediated environments. Asian Education Studies, 3(1), 18-28. https://edtechbooks.org/-ToZh

[1] In foreign language teaching, learning materials are considered authentic if they were not artificially created and for intentional pedagogical use in a language course but are taken out from authentic contexts (e.g.: a piece of a newspaper article or film).