In this S-STEP study, we analyze how our lived experience intersects with our ability to authentically work towards reconciliation and decolonization in both our personal life and professional practice as a teacher educator. The purpose of this study is to look back to look forward, forging a new path towards personal reconciliation and decolonization. Loughran (2002) reminds that context is everything in S-STEP research. The political, social, and cultural context for this study is Canadian reconciliation as per the Truth and Reconciliation Report (TRC), released in 2015 which revealed the true history of Indigenous cultural genocide through the Indian Residential School System (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015).

Within the TRC Calls to Action are specific recommendations for educators. This study is a response to this call, as a commitment for personal and professional reconciliation and decolonization of teacher educator practice. The setting for this study is complex, as we examine some of our life’s memories of Indigenous peoples through images and narratives. The settings move across Canada, following our own complex path from naïve consciousness to critical consciousness.

S-STEP provides the theoretical and methodological framework for this study as an approach to look at self through both a personal lens and the lens of a critical friend. The research literature informing this study is within settler identity research (Battell & Barker, 2015) and Indigenization plus decolonization of educational practices (Pidgeon, 2016; Hare, 2016).

Aim of the Study

The research question for this study is: What are our historical understandings of Indigenous Peoples and their histories, cultures, and contemporary realities and how do these understandings influence our personal and professional process of reconciliation and decolonization? Georgann was prompted to begin this process while participating in a Massive Open Online Course created and presented by Jan Hare (2016, University of British Columbia): “Reconciliation Through Indigenous Education”. In the introduction to the course, Hare suggests that students go beyond the present and look back at the ways in which perspectives, attitudes, and actions in Indigenous/settler relationships intersect with personal history. Subsequent conversations with Georgann prompted Edward (Ted) to reflect back on his childhood memories and lived experiences connecting to truth and reconciliation.

Following Clift and Clift’s (2017) framework for self-study memory work, which recognizes the relevant and significant links between personal and professional constructions of self-as-teacher, and Hare’s (2016) strategies to decolonize my thinking about Indigenous-settler relationships, we engaged in this S-STEP research to investigate our own complicated history concerning Indigenous-settler relations at personal, familial, and collective levels. This study looks back to look forward, situating our personal reflections of Indigenous-settler relationships in context, and as such, informs reconciliation and decolonization of teacher educator practice.

Methods

Memory work is an approach to self-study that encourages teachers to examine their own lived experiences (Clift & Clift, 2017; Pithouse-Morgan, et al., 2012). Memory work frameworks guide this study as we work through a journey of remembering my social and cultural experiences with Indigenous peoples, our historical knowledge of colonization, and our understanding of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015).

Narrative metissage is an arts-based method of inquiry that interweaves personal stories and serves as a process of uncovering and co-constructing knowledge about self, about others, and about the world (Etmanski et. al., 2013; Lowan-Trudeau, 2018). It is “a way of merging and blurring genres, texts, and identities; an active literary stance, political strategy and pedagogical praxis: (Chambers, et al., 2001, para 1). Donald (2009; 2012) further refines metissage as the critical juxtaposition of Western and Indigenous narratives of place. Narrative metissage provides a way to systematically explore my lived experiences in the context of my professional practice as a teacher educator.

The analysis of the narratives reveals a significant shift in critical consciousness about ourselves as teacher-educators. In this study, we grouped the narratives and images into three themes: naïve levels of consciousness, a non- questioning and accepting relationship with Indigenous Peoples (It is the way it is), interpretive levels of consciousness, a questioning of socio-cultural contexts of my relationship with Indigenous Peoples, (Why is it this way?) and critical levels of consciousness, an analysis of historical and social contexts of colonization (How can we change our ways?).

We shared our narratives and images with each other as critical friends and we regularly engaged in critical discussions for clarity and perspective. Loughran and Northfield (1998) emphasized the need for S-STEP researchers to collaborate by checking data and the interpretations of that data with others in order to allow for perspectives to be challenged. Additionally, they proposed that self-study researchers work with colleagues to broaden validity of their work and push a reframing of teaching practice.

The following narratives represent some of our memories. The memories inform our critical consciousness, and in turn, inform a transition in personal and professional teacher- educator practice.

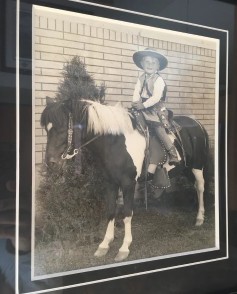

Georgann: Real Injun

Real Injun (2009, National Film Board of Canada) is a documentary that examines the portrayal of North American Indigenous Peoples through the beginning of the film industry to the present. This documentary accurately captures my earliest childhood memories of the relationships between cowboys and Indians. As I child, I was obsessed with horses, and by extension with cowboys and cowgirls. I viewed them as the heroes of the stories I read, the TV shows I watched, and the films I went to see at the cinema. Indians were either sidekicks (The Lone Ranger and Tonto) or savages (Chief Sitting Bull). These were the assumptions I held in my early memories. I always had a toy horse, and my costumes and outfits were connected to being a Cowgirl, never being an Indian. In my early memories, I never questioned the takeover of the land, the displacement of people, or the violence of the battles. I simply assumed that Cowboys were better than Indians and that Indians were to be conquered and captured. I assumed that this was the only way to make Indians into Cowboys.

Figure 1

Girl on pony. (Cope Watson, 1961)

Ted: A Childhood Anthropologist’s Story

As recounted in a previous narrative paper (Howe & Xu, 2013), in recent years I have reflected on my own connections to First Nations Peoples and the implications of decolonization, truth, and reconciliation.

In the 1970s, growing up in Victoria, British Columbia (BC), in a middle- class, predominantly White neighbourhood, I experienced first-hand the growing pains of a nation in transition and in search of a multicultural identity. While I learned about other cultures, they were rarefied, foreign, exotic, and distant. Even our study of West Coast Indians seemed far removed from every day — as if it were an ancient civilization. I recall visiting the Royal BC Museum in grade four to view Indian artifacts and to experience a potlatch feast and celebration. I ate smoked salmon and tried dried seaweed for the first time. But this was merely a perfunctory gesture. Why didn’t our teacher invite local elders to our classroom to learn about people living within our own community? In fact, one of the star players on my soccer team was of First Nations background. We could have asked him to invite his parents or grandparents to teach us about their culture. Instead, we made fun of this boy making racist comments like, “let’s shmoke shome shamon”. Not surprisingly, he was ashamed of his cultural heritage. Thus, we studied First Nations traditions, but we didn’t critically question pervasive racist attitudes and the assimilation policies of the government nor did we learn about the Indian Residential Schools and systematic stripping of culture.

Figure 2

Royal BC Museum. (Howe, n.d)

Georgann: A Tent in the Woods

I am not an Indigenous person, and I do not necessarily feel a strong sense of place or a strong connection to the land. I struggle to make a connection to this concept. When I reach back into my memories of place, I experience a kaleidoscope of living and being in many places, but, of always feeling like a visitor. Except in one place. “When I am in this place, I can feel my roots stretch right through my body into the ground”.

These are the words I shared with a cousin when we were in our thirties at a family gathering. We grew up together on our collective familial land: a tract of waterfront land with 7 sites: each site occupied by relatives of my family. It is called Cope Lane. It is my home. In this place, amongst my parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, I feel an authentic sense of place and a deep connection to the land. I know everything about this place, and I feel connected to the animals, the lake, the beaches, the jetties, the gardens, and the woods... Especially the woods.

When I was 7 years old, I pitched a tent between my family’s home and my grandparent’s home in the little plot we called ‘The Woods’. I set up a bed, I had a flashlight system for light, and I had snacks and drinks. I also brought along my dog, Susie. Susie and I lived in that tent for the summer. I was never afraid, as I felt I was home, and that there was nothing to fear in the woods. I was happy there. Cope Lane is the only place I have ever felt that I had a clear sense of place and where I knew exactly who I am and where I come from.

Figure 3

A tent in the woods. (Cope Watson, 1964)

Having been born and raised just a stone’s throw from the Pacific Ocean, I have always felt a close connection to the sea. During the time I’ve lived in land-locked regions, I have felt disconnected, as I long for the serenity of waves lapping on the shore. I believe there is an island mentality or way of being that relates well to Indigenous ways of knowing and the importance of learning from the land (and sea). A special place for me is the family cabin on North Pender Island near Victoria, BC. My family discovered this unique spot during our boating and exploring of the Gulf Islands in the mid-1970s. When we outgrew our sailboat, my parents bought recreational property there, where we tented for years before building a cottage in the early 1990s. There is a common expression among Penderites, “Relax... I’m on Pender Time” and that saying reflects the slow pace of life on Pender. So, Pender life is not for everyone, as we have no Internet at our cottage and some folks might be prone to “cabin fever” as there is no one around for miles. But I like it that way. It is the one place I can be truly off the grid, digitally disconnect and regain a sense of connection to the land. Days can go by without seeing a soul. But on the other hand, there is a strong sense of community amongst Penderites and I have learned a great deal during the times I have retreated there for respite. For example, there is no garbage collection on Pender. Residents must think carefully before throwing out anything. Each bag of garbage costs $5 to dispose of and you must drive your garbage to a private contractor to have it taken care of. There is a recycling coop where residents sort their own plastics, papers, metals and so on. Previously, I had no knowledge of the vast array of recycling materials and how someone must go through these by hand in order to ensure that they are indeed recycled. Many people on Pender find effective ways to re-use materials. For instance, my children helped build a sustainable house out of pop cans! I used our weekly garbage and Pender recycling as a “teachable moment”. I subsequently developed a lesson on classification and sustainability. My family has learned the importance of recycling and we have a deep appreciation for the fragility of our earth. It reminds me of a local Kamloops elder that often tells us that he used to be able to drink the water from our local rivers but those days have long gone as we continue to pollute our environment.

Figure 4

Pender Island. (Howe, 1970s)

Georgann: Colonizing Practices

For many years, I taught a parenting program called Nobody’s Perfect, a federally sponsored program with a target group of young, single, socially or geographically isolated parents, or parents who have low income or limited formal education (Nobody’s Perfect, n.d.). Nobody’s Perfect was always co-facilitated by one community worker and one public health nurse.

Once, and only once, we facilitated a course for Indigenous parents living on reserve. I was excited about this opportunity since I had also worked on other community services committees and initiatives in the area and I knew this particular band was impoverished. I prepared for the first class exactly the way I prepared for all of the classes, I organized the venue with the help of the band office, I made childcare arrangements for the children of the participants, I organized the course material and I purchased the food for the common meal. I was all set to go.

It was a disaster! First, parents wanted to be with their children, and they did not want them in a separate space. The books and the course materials went unopened, and the food remained untouched. We sat in a circle, which was common practice for this group, but since there was no talking circle process, the parents remained silent. The agenda, which was normally co-composed between facilitators and parents, was never developed. We eventually made it through the 6-week program, but it was rough going, and I left that program with many questions. This was a turning point, a point where I had to begin to question how culture, history, and knowledge were contextualized.

Figure 5

Nobody’s Perfect Parenting Program at Kamloops Residential School. (Nobody’s Perfect, 2020)

In the late 1990s, we moved to another ski resort near Kamloops. There is a point when driving in that area where you exit the TransCanada Highway to head north on the Yellowhead Highway. As you move around the exit, a large red brick building comes into view. It is one of the last standing Indian Residential School buildings in the country: The Kamloops Residential School. The image, for me, is haunting, particularly in the dark when it is lit up. It is impossible to ignore the building, and it is a symbol of my changing consciousness. Only in the late 1990s did I begin to question the Indian Residential School system, and to think about the children that attended there. I was still very naïve, and I did not make any connection to colonization, I did not know about the treaties, the Indian Act, or the land disputes. I began to think about the children and to learn about the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse they endured at the schools. But there was no way to access the Internet for me then, and I could only begin to educate myself through common knowledge and stories. Ironically, the stories came mostly from outside the Indigenous community and were only partial truths.

Figure 6

Kamloops Residential School. (Kamloops Residential School, 2020)

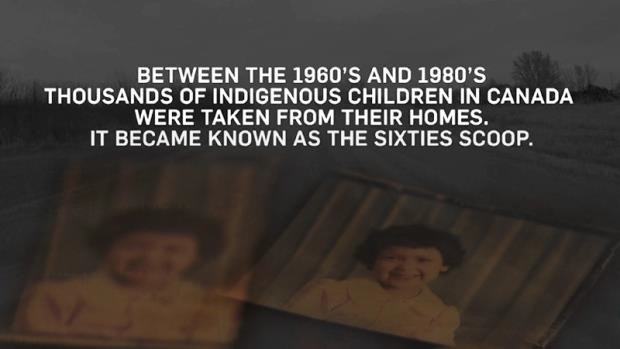

Ted: The Sixties Scoop

I invited an Aboriginal Education worker from our local school district to be a guest speaker in the second to last lesson of my class. I asked her to share with us Indigenous pedagogies including oral traditions. I was thrilled when she indicated that she wished to embed her personal story and chose to share her own lived experience. This tied-in nicely with my previous lesson on narrative inquiry and would provide a bridge to the final lesson on Indigenous ways of knowing, with another guest speaker and with our artifact sharing circle. But I was completely unprepared for what transpired during her riveting 90-minute lesson. It moved me greatly and caused me to reflect deeply on my own personal practical knowledge (and more importantly, on my lack of knowledge in this area).

Our Indigenous guest speaker gave a heartfelt and thought-provoking presentation on the 60s Scoop (2020). She tied this shameful piece of modern Canadian history to other stories of lived experiences and to her own very personal story. It is astounding to think that between 1955 and 1985, more than 20,000 children were taken from their Indigenous mothers and put up for adoption to White families as assimilation. It is shocking that most Canadians do not know the truth. Until this presentation, while I had knowledge of the Residential Schools, I had never heard of the 60s Scoop. She asked us to reflect (Think, Pair, Share) and to share with the class how her story changed our way of thinking. In a moment of profound epiphany, in the middle of this activity, I was struck by the possibility that my own second cousin could also be a 60s Scoop baby!

In a subsequent conversation with my second cousin, I have learned that she was adopted into our White settler family in 1966 at the tender age of 9 weeks. More than 30 years later, she learned of her Indigenous heritage and re-connected with her Cree birth mother. Much of their shared history until then had been kept secret. Her adopted mother’s meta-narrative was that her birth mother was French-Canadian. She grew up thinking that she was part French-Canadian as being an Indian was not something to be proud of back then. As a young adult, my second cousin found all this difficult to process but with counseling she has been able to deal with her identity issues and her mixed feelings. But it is too late to embrace this part of her family heritage. It is lost forever.

Georgann: That Didn’t Happen!

My first real experience with the null curriculum came when I was a teaching assistant in a year one Women’s Studies course. Colonization and the Indian Residential School System, as well as the lesser-known 60s Scoop were part of the curriculum (60s Scoop, 2020). I had access to scholarly work and to research on Canada’s true history with Indigenous Peoples. My critical consciousness increased, and I began to make sense of some of my assumptions about, and experiences with, Indigenous Peoples. I was able to share this knowledge and understanding with many students, friends and family members. The null curriculum of Canada’s social and historical relationships with Indigenous people was finally being addressed in some educational contexts.

Not all students, friends, or family members were willing to look beyond the naïve to the critical. I often heard comments during lectures that “Oh, that didn’t really happen, this just can’t be true”. Or: It wasn’t that bad, the children had a roof over their heads, a bed, and food to eat. And they were getting a good education”. These forms of resistance were major obstacles, as the voices of the Indigenous community were absent from the conversation. I tried to share knowledge with everyone I knew, not as a way of disdaining or proselytizing, but as a way to confront the null curriculum. But often, they just didn’t want to know. Pushing back against the narrative that Canadians are not racist but welcoming of all people is a pervasive and perpetual challenge.

Image 7

60s Scoop Image. (60s Scoop, 2020)

Ted: Witnessing History, Truth and Reconciliation

When I moved to Thompson Rivers University, in 2014 one of the first courses I was asked to teach was EDEF 3100 History of Education. This core educational foundations course is not a popular one because many of our Bachelor of Education students often don’t see the relevance of history in classroom teaching. It is challenging to teach educational foundation courses, but I was keen to make this course relevant and to introduce students to teaching for social justice, decolonization, and reconciliation. Perhaps, as a new faculty member, it is not surprising that I was given this difficult course that few people want to teach. While First Nations history was embedded in this course, it was buried in a textbook that was written many years prior to the TRC. So, I attempted to find ways to update the curriculum and to Indigenize my teaching by reaching out to Indigenous faculty and the community. One of the most memorable lessons was a field trip to our local Secwepmec museum situated next to the Kamloops Residential School, which to my surprise was still in operation until 1996. My teacher candidates watched a documentary and were given a presentation as well as a guided tour of the school. We ended the lesson with a talking circle facilitated by an Elder who was a residential school survivor. This was a very moving experience for me. Some students were brought to tears. It was particularly difficult for those of us who had grown up in a Christian home to see what had transpired at the hands of the Catholic church and the Anglican church (my own faith). But it was when I was asked to develop the online version of History of Education that I really came to understand the lived experience of this Elder survivor. I interviewed her on a cold winter’s day beside the Thompson River where she recounted her story. I will never forget the look in her eyes as she told me of the abuse she endured as a little girl, removed from her parents. I was shocked by the harsh words she used to describe Sir John A. MacDonald, our first Prime Minister, and a man that I had been taught to admire. In June of 2015, I witnessed history in the making when Justice Murray Sinclair presented the TRC Report and addressed Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in the House of Commons. It was especially meaningful to me in light of this critical incident. This was a turning point for me on my reconciliation journey.

Image 8

Student Trip to Kamloops Residential School. (Howe, 1970s)

I had never considered an exploration of my own identity as a settler. My consciousness began to change as I moved to communities with higher Indigenous populations. As I interacted more frequently with Indigenous Peoples, I became more curious about their cultural and social patterns and behaviours. This curiosity led to a focused study of my own historical relationships with Indigenous people, leading to changes in personal and professional behavior and practices. My personal process of reconciliation and decolonization is emerging, as evidence in both professional practice and personal life. It is humbling to learn about colonization and the intergenerational trauma of Indigenous Peoples resulting from the Indian Residential School. The First Peoples Principles of Learning (FPPL) now guide my personal and professional practice.

Promising Pedagogies of Practice and Final Thoughts on Truth, Reconciliation, and Decolonization

The campuses of Thompson Rivers University are located on the traditional and un-ceded territory of the Secwepemc Nation within Secwepemcul'ecw. As we share knowledge, teaching, learning, and research within this university, we recognize that this territory has always been a place of teaching, learning, and research. We respectfully acknowledge the Secwepemc—the peoples who have lived here for thousands of years, and who today are a Nation of 17 Bands.

We acknowledge Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc. We acknowledge T'exelcemc and Xat'súll. We acknowledge the many Indigenous peoples from across this land. Across Canada, universities are leading the way in our response to calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (2015). But we have a lot more work to do. At formal gatherings, we begin by a territorial acknowledgment, such as the one above. But we must go beyond superficial gestures and merely reciting a highly scripted text. As Chair of the School of Education within my university, and as a result of conversations such as the one shared here, I have initiated a new oral tradition whereby we start our meetings with a story of experience, tied to the land. That is one way to go beyond reciting the territorial acknowledgment. In this way, each of us can reflect deeply on our own personal and professional response to the TRC. This study has prompted me to reach out to faculty to make deeper connections to the TRC and to honour the Indigenous Peoples who have inhabited these lands for thousands of years. Our narrative metissage and other narrative methodologies as well as S-STEP and reflexive turns, could provide all educators across Canada and elsewhere with a path forward, as we struggle with the challenges posed by truth, reconciliation and decolonization.

References

Battell Lowman, E. & Barker, A. J. (2015). Settler: Identity and colonialism in 21st century Canada. Winnipeg: Fernwood Publishing.

Chambers, C., Donald, D., & Hasebe-Ludt, E. (2002). Creating a curriculum of metissage. Educational Insights, 7(2).

Clift, B. C. & Clift, R. T. (2017). Toward a pedagogy of reinvention: Memory work, collective biography, self-study and family. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(8), 605-617.

Cope Watson, G. (1961). Girl on pony [Photograph]

Cope Watson, G. (1964). Tent in woods [Photograph]

Donald, D. (2009). Forts, curriculum and Indigenous metissage: Imagining decolonization of Aboriginal-Canadian relations in educational contexts. First Nations Perspectives, 2(1), 1-24.

Donald, D. (2012). Indigenous metissage: A decolonizing research sensibility. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 25(5), 533-523.

Etmanski, C., Wiegler, W. & Wong Sneddon, G. (2013). Weaving tales of hope and challenge: Exploring diversity through narrative metissage. In D. E. Clover & K. Sanford (Eds.), Arts-based education, research and community cultural development in the contemporary university: International perspectives (pp. 123-134). Manchester University Press.

First Peoples Principles of Learning. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/kindergarten-to-grade-12/teach/teaching- tools/aboriginal-education/principles_of_learning.pdf

Hare, J. (2016). Reconciliation through Indigenous education. EdX, MOOC. Howe, E. R. & Xu, S. J. (2013). Transcultural teacher development to foster dialogue among civilizations: Bridging gaps between east and west. Teachers and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 36, 43-53.

Howe, E. R. (n.d). Royal B.C. Museum [Photograph]

Howe, E. R. (1970s). Pender Island [Photograph]

Howe, E. R. (1970s). Student trip to Kamloops Residential School [Photograph]

Howe, E. R. & Xu, S. J. (2013). “Transcultural Teacher Development to Foster Dialogue Among Civilizations: Bridging Gaps between East and West” Teachers and Teacher Education: An International Journal of Research and Studies, 36, 43–53.

Kamloops Residential School. (2020). Kamloops Residential School [Photograph] https://tkemlups.ca/files/2014/02/tkemlups.jpg

Loughran, J. J. (2002). Understanding self-study of teacher education practices. In J. Loughran & T. Russell (Eds.), Improving teacher education practices through self-study (pp. 239-248). Falmer.

Loughran, J. J., & Northfield, J. (1998). A framework for the development of self-study practice. In M. L. Hamilton (Ed.), Reconceptualizing teaching practice: Self-study in teacher education (pp. 7–18). Falmer Press.

Lowan-Trudeau, G. (2018). Narrating a critical Indigenous pedagogy of place: A literary mettisage. Educational Theory, 67(4). 509-525.

Nobody’s Perfect (2020). BC https://www.bccf.ca/program/1/

Nobody’s Perfect (2020). Parents in group meeting [image]. British Columbia Council for Families. https://keltymentalhealth.ca/sites/default/files/resources/training- entrainement.jpg

Pidgeon, M. (2016). More than a checklist: Meaningful Indigenous inclusion in higher education. Social Inclusion, 4(1), 77-91.

Pithouse-Morgan, K., Mitchell, C., & Pillay, D. (2012). Editorial: Memory and pedagogy special issue. Journal of Education, 54, 1-6. 60s Scoop (2020). https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/sixties_scoop/

60s Scoop (2020). Image. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/polopoly_fs/1.3826866.1520033777!/httpImage/image.jpg_gen /derivatives/landscape_620/image.jpg

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume One: Summary. Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future. Lorimer.