In this chapter, I explore the potential for mixed methods action research critically evaluated from a feminist orientation to expand feminist knowledge building in online higher education programs, curriculum and instruction, in particular online grading and feedback processes. My approach is simultaneously reflective and forward focused. I also explore how digital tools might be used as part of this broader research approach to both promote and support feminist pedagogy and thinking. A recent mixed methods action research study that explored the impact of a web-based comment bank intervention on online pedagogy serves as a site of critical inquiry.

In a recent mixed methods action research study (Schneider, 2020), I explored the impact of a collaborative, web-based comment bank on online pedagogy. In this chapter, I critically evaluate that research study through a feminist lens. This study originated out of my own experiences both teaching in online learning environments and simultaneously serving as a peer coach and mentor in the same spaces. In this role, I worked with online instructors who consistently shared their frustrations with unexpectedly high (and increasing) time demands associated with increasing class sizes and an associated limited ability to provide individualized and student-specific feedback on written assignments. I, too, would often experience similar challenges and frustrations in my own teaching and learning. At the same time, I was often asked to review student complaints and disputes associated with perceptions of a lack of timely, specific, and/or personalized feedback on assessments and written submissions. Instructors and students both experienced and shared persistent challenges that impacted self-efficacy and confidence in online teaching. While the literature includes a variety of strategies to adopt a feminist digital pedagogy in course design and teaching, there are fewer examples that offer insights on how to do so in connection with grading and feedback processes. I undertook this action research study and associated digital tool development work with the hopes of impacting positive change in this area.

In this chapter, I reflect on the action research process and explore the potential for mixed methods action research to expand feminist knowledge building in the context of online higher education programs, curriculum, instruction, and, in particular, grading and feedback processes. I use feminist pedagogical and methodological frameworks to critically examine the research. My approach is simultaneously reflective and forward focused. As a part of this action research and reflective inquiry, I also examine how digital tools might be developed and incorporated as part of this broader action research approach to further promote and support feminist pedagogy and thinking and, relatedly, how I and others might “achieve feminist ends using digital tools” in this context (Golden, 2018, para. 2). Using feminism as a lens to critically examine my practice necessitates ongoing critical reflection and inquiry of the study itself, as well. This chapter, and the reflections contained herein, are part of this process of critical analysis and ongoing exploration.

I begin my discussion with background information on the web-based comment bank I co-designed with input and feedback from university instructors, followed by an overview of the research questions and methods developed and applied in an illustrative mixed methods action research study context. I conclude with a reflection on the value of mixed methods action research (Endnotes 1 and 2) from a feminist lens as well as its complexity, including related issues of bias, reflexivity, assumptions, and voice.

The Feedback Project: A Web-Based Comment Bank

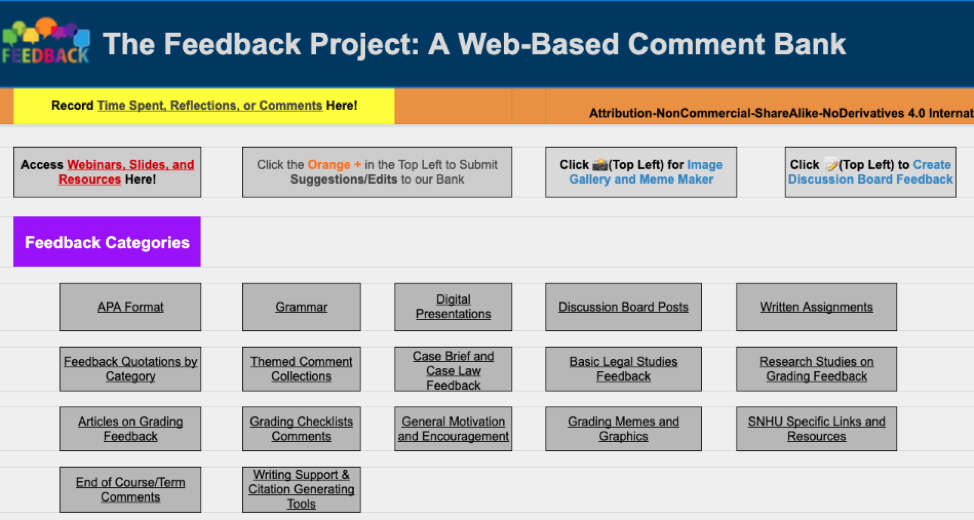

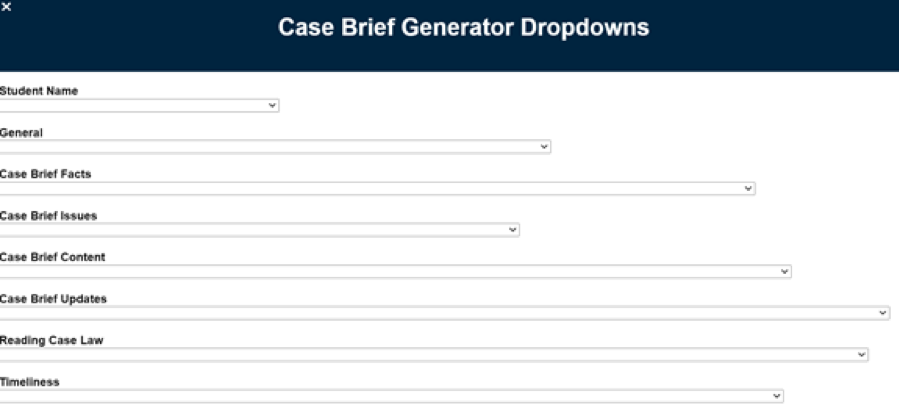

In general, a comment bank is a library of customizable and personalizable feedback comments (or statements) and resources that are organized by category and address a range of student work. The comment bank used in this study (Image 1) was designed with intentionality and express acknowledgment of the struggles that have long accompanied the grading and feedback processes. Challenges such as instructor fatigue, stress, and ambiguity (Hattie & Clarke, 2019; Tierney, 2013) as well as bias and equity (Schinske & Tanner, 2014; van Ewijk, 2011) have long been noted. In this study, these challenges were intentionally confronted—as encouraged by feminist pedagogy—and collaboration was used to explore potential solutions to the above-noted challenges.

Image 1

Home-page of the open-access web-based comment bank created for this study (https://www.thefeedbackbank.com/).

The site design welcomes contributions from readers. Contributions can be shared and submitted here as well as via links embedded on the comment bank. New comments and comment categories are regularly added to the site. Existing comments can be copied, pasted, and customized to suit individual assignments and student needs (for an example, see Sample Comments to Promote Dialogue below). Users can adapt, share, and submit requests for new comment types and categories.

Sample Comments to Promote Dialogue

- I enjoyed reading your work! After you've had time to review my reflections, please reach out with questions or simply to continue our dialogue on your work.

- Thank you for your hard work! I've shared some initial thoughts on your paper. Keep in mind that I am only one reader and these are only recommendations. I hope you find my feedback helpful. Please reach out via email to explore these points and my suggestions further!

- Let's chat! My suggestions are just that - a suggestion! I hold weekly office hours and would be happy to dig deeper. Hope to hear from you!

Feminist digital pedagogy informed and influenced this action research inquiry as well as the related development of the study’s intervention, a web-based comment bank. Golden (2018) describes a feminist digital pedagogy as one that “engages goals, topics, and projects that demonstrate equality – fairly addressing students and texts, including formerly overlooked voices – using digital tools” (p. 42). Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007) write of feminist researchers as “an integral force” (p. 251) with powerful implications that include—and even extend beyond—concerns of sexism, oppression, patriarchal structures, and associated subjugation such as those described by hooks (2015). hooks (1989) explains that,

Feminist education— the feminist classroom—is and should be a place where there is a sense of struggle, where there is visible acknowledgment of the union of theory and practice, where we work together as teachers and students to overcome the estrangement and alienation that have become so much the norm in the contemporary university. (p. 51)

In reality, the forces attributed to and acknowledged within feminist researchers shape all research topics and methods, including, as discussed in this chapter, the referenced action research on issues associated with higher education, online learning, and grading feedback. Moreover, feminist inquiry might further efforts to help all individuals both identify their unique voice (amidst a world with innumerable voices seeking to be heard) and belief in the inherent value of that voice (Gay, 2014).

Research Questions and Methods

My research questions were designed to generate feedback and data on issues of instructor online teaching efficacy, collective teaching efficacy, and perceptions and attitudes surrounding the online grading and feedback processes. The impact of interventions on efficacy are typically measured using quantitative approaches such as pre- and post- surveys (Deller, 2019). Surveys are often chosen due to factors such as cost, time, simplicity, and ease of use (Ebel, 1980). In this study, however, and in a manner that embraces feminist pedagogy as “a pedagogy that is at-once reflective and realistic in its relationship to empowerment” (Bond, 2019, para. 1), I deliberately chose a mixed-methods action research design as it recognizes that “[a]ttending to the naturalistic conditions and multiple layers of classroom life demands a subjective, holistic, and flexible approach” (Klehr, 2012, p. 123).

Mixed methods action research affords researchers both flexibility and reflection-based analysis. These attributes are both especially valuable for researchers interested in the potential for intentionally designed digital tools to break down existing structures and associated—often deeply embedded—processes in digital spaces and reflective of tenets "core to the feminist learning experience: breakdown of hierarchy, participatory learning, and social construction of knowledge" (Milanés & Denoyelles, 2014, para. 8).

Research participants included 18 instructors at a private, U.S.-based university that serves a global student population. I collected quantitative data via pre- and post-intervention surveys. Qualitative data was collected via open-ended survey questions as well as through informal interviews, conversations with participants, and document analysis.

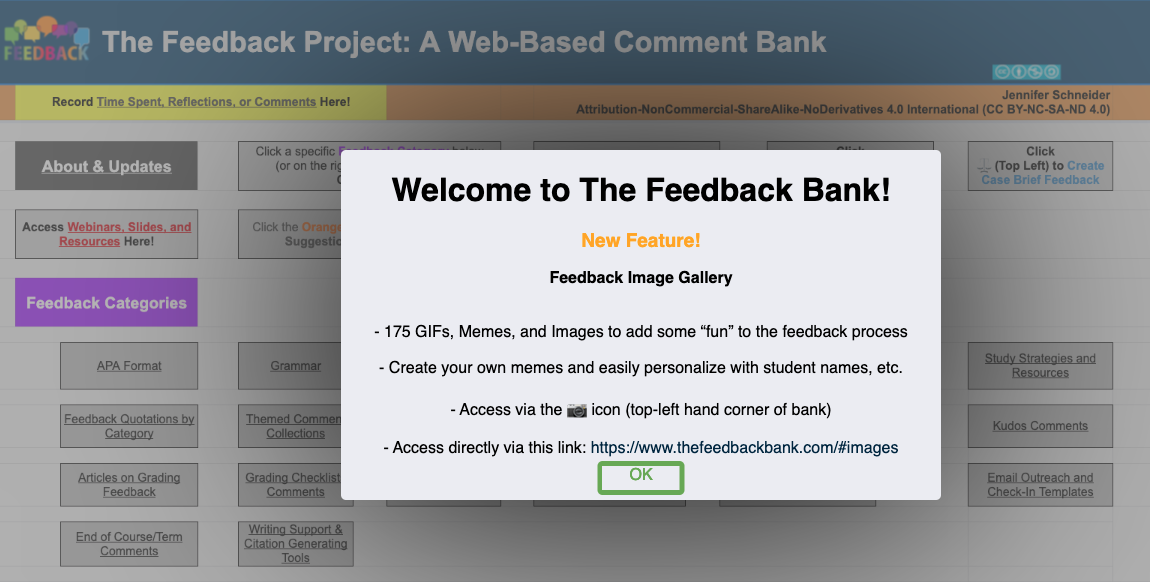

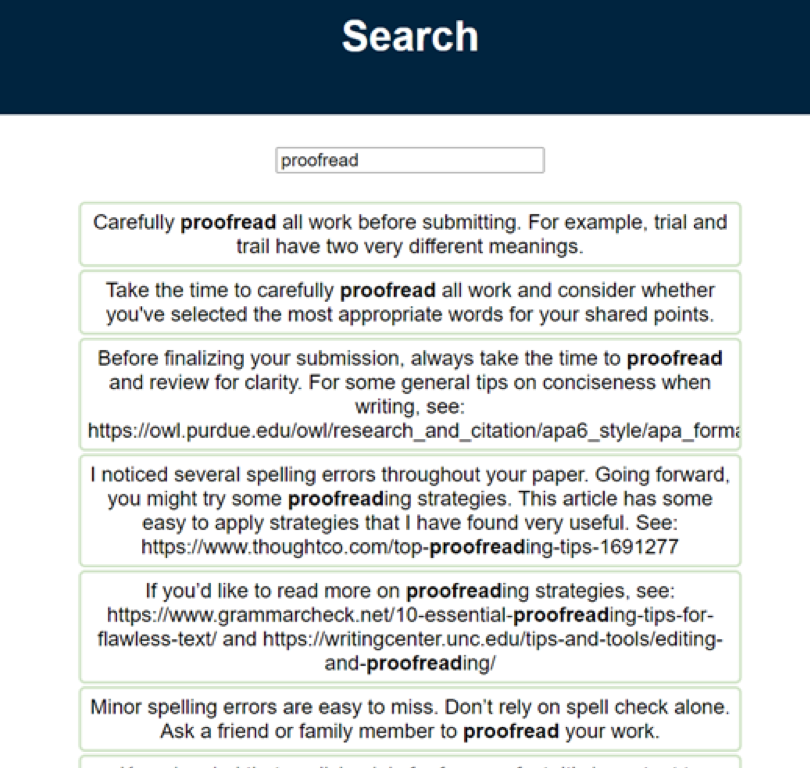

All participants were actively engaged in the comment creation (and associated knowledge construction) process, including through the submission of new comments for inclusion in the comment bank as well as through the customization and personalization of comments copied from the bank. The feedback process (and development of both the comment bank and associated features and tools) was ongoing, iterative and looped, in that participants would access the bank, review, personalize, and apply comments, and then share new comments on an ongoing basis. Updates were highlighted via rotating carousel messaging (Image 2).

Image 2

Updates highlighted via rotating carousel messaging.

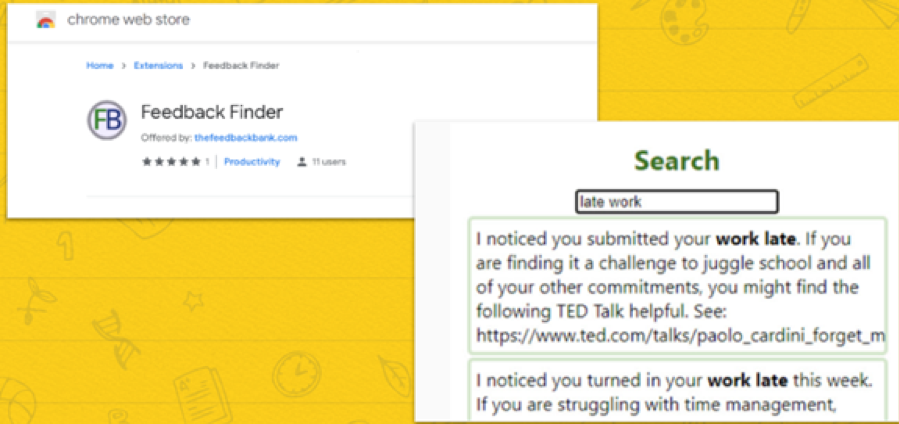

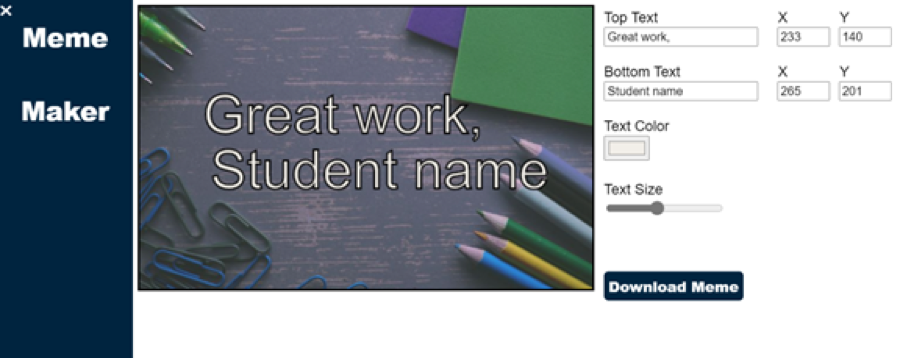

Many features designed and added during the course of the action research study were direct responses to participant requests. For example, a section with “Kudos” comments (see below for examples) was created in response to a participant request. The Feedback Finder Chrome Extension (see Image 3 for an example) was also created as a result of a participant’s desire for a more streamlined copy and paste functionality. The comment bank’s image gallery and meme generator (Image 4), the case brief feedback generator (Image 5), and global search functionality (Image 6) were also inspired by, and created in response to, feedback shared by participants throughout the course of the action research study. Ongoing communications provided opportunities for peer sharing as well as the social construction of knowledge. Development was iterative and dynamic. Anonymous surveys embedded throughout the feedback bank also promoted the free and honest sharing of feedback and improvement requests in an ongoing and simultaneously reflective and forward-focused manner.

Kudos comments created in response to a participant request

- Kudos! I’m so impressed by your improvement from last week to this week. Your writing is much stronger and your associated support is much more developed. For example, ___. I appreciate your excellent efforts! Please keep up the good work!

- Kudos! Really nice work on your APA format! You’ve improved significantly from the beginning of the term. Well done!

- Kudos! Really nice work with your writing. I’ve noticed significant improvements in the development of your arguments. For example, ____.

Image 3

A “Feedback Finder” Chrome extension developed in response to a participant request.

Image 4

A personalizable image gallery and meme generator developed in response to a participant request.

Image 5

Case Brief Narrative Feedback Generator created in response to a participant request.

Image 6

Global Search Functionality created in response to a participant request.

Given the ongoing interactions between myself (as both researcher and practitioner) and participants, ongoing reflections on positionality were imperative. Positionality was considered with intentionality at all points and junctures of the action research study process. By way of example, in connection with this action research study, I might be characterized, at least in part, as an insider in collaboration with other insiders. My associated positionality remained a critical and visible (as encouraged by feminist education) component of all aspects of the action research study and my interactions and collaborations with study participants. For example, throughout the entirety of the study I held a role as a researcher and, in my capacities as an online course instructor, mentor to colleagues, and peer coach, as well as a practitioner. My online instructional work as well as my work involving virtual peer mentorship and coaching occurred in parallel with my associated action research. I used ongoing reflection and journaling as tools to ensure I maintained, to the greatest degree possible, both a critical perspective and associated awareness of my positionality throughout the entirety of my study. Both reflection and journaling provided valuable opportunities to pause and focus on the action research experience. The time afforded both consistently yielded original insights including patterns and trends in experiences and related reactions and desires, all associated with the grading and feedback processes.

I share the foregoing out of a belief that these are areas I think everyone conducting mixed methods action research should consider at all steps of the action research process. In this particular action research study, there were times I struggled with my multiple roles (researcher, online instructor, peer reviewer, and mentor, for example). Those struggles consistently yielded valuable insights as well as original features (for example, a rubric-aligned discussion board feedback generator) that were ultimately developed and added to the comment bank. However, the mixed methods action research process not only offered opportunities to gain rich insights into the impact of the intervention (the web-based based comment bank), but also offered ongoing opportunities to reflect on and learn from these struggles (including, for example, the immense benefits of peer communication and safe spaces to voice challenges with grading), most if not all of which mirror the realities of our work and practice in online teaching modalities.

In the following sections I elaborate further on issues of reflexivity, choice of methods, bias, and positionality in mixed methods action research through a feminist lens and also highlight some additional areas for consideration.

Reflexivity

The breadth and potential power of feminist theory and feminist digital pedagogy, in particular, in this context and others, are not unlike that associated with reflexivity in other aspects of one’s work and practice. Reinharz (2011) writes of reflexivity as both a theory and a process, where one’s work incorporates intentional and conscious efforts to reflect on, consider, and account for the broad impact of one’s thinking, actions, and perceptions on others. In my own practice (including and extending beyond research applications), reflexivity plays an important role in online course design, pedagogy, teaching, and educational research design. I am not alone. For example, Crawley (2008) writes that educators “must be reflexive about our pedagogical goals and techniques” (p. 13). Similarly, Altman and Leeman (2020) write of the importance of reflexivity and related issues of authenticity and compassion for “addressing the whole human being in … learning experience design” (p. 5).

Altman and Leeman encourage others (educators and researchers included) to “continually evaluate [their] own mental models of what it means to learn” because

this kind of attunement to self and those with whom we work serves to create richer relationships between faculty and their students in distance education settings, and in a profound way, connects the LXD [learning experience designer] to the very personal and emotional nature of adult learning as well in a way that impacts course design. (p. 5)

These points and reflections also relate well, I believe, to action research study design. After all, teaching, not unlike feminism, is a complex activity. Reflexivity is an important component of both practices. For example, Beunen, van Assche, and Duineveld (2013) argue for “greater reflexivity in planning and design education” (p. 2) and write that

Reflexivity is understood as a sustained reflection on the positionality of knowledge and presented as an opportunity to strengthen the academic dimension of planning and design curricula. The planning and design curricula, we argue, cannot tackle these issues without a deeper and more systematic self-reflection, a reflection on the disciplines, their teaching, on the role of planners and designers in society. (p. 2)

Feminist theorists and research also adopt a reflexive approach to research, as conveyed (in part) through Jorgenson’s (2011) exploration of reflexivity in feminist fieldwork and “the importance of acknowledging personal viewpoints on issues including gender, professional status, and race and their impact on social science research” (p. 115). Whereas feminism and reflexivity are both ways of thinking and processes by which one engages in a conscious effort to reflect on the impact of one’s perceptions and actions on others (Reinharz, 2011), mixed-methods in my research emerges as a tool, and a powerful one at that, to act with intentionality and to actively “question language…the repository of our prejudices, our beliefs, our assumptions” in the manner Adichie (2018, p. 16) urges, in order to better understand the world (Leckenby & Hesse-Biber, 2007).

As Merriam and Tisdell (2016) make clear, “[n]o classroom teacher...will want to experiment with a new way of teaching...without some confidence in its probable success” (p. 237). The study (and related research design and study interventions) described in this chapter were no exception. As such, the described methods of data collection and subsequent analysis were all designed to increase and maintain both study trustworthiness and rigor. Ethical issues, including but not limited to “reciprocity to participants for their willingness to provide data, the handling of sensitive information, and disclosing the purposes of the research” were considered in detail and in an ongoing manner (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018, p. 181). I also remained acutely mindful of the fact that answers are inevitably heavily shaped by the questions that are asked (Taylor, 2016). While collecting and analyzing data, for example, I remained hyper aware of, and attentive to, the many different types of influences that might impact the “ordinary” voices of others during data collection. In this way, I employed ongoing reflection and consideration of not only the language used, but also my positionality, reflexivity, and bias (further explained below) at all points and stages of the action research study.

Using Mixed Methods

Mixed methods research considered through the lens of feminist theory and pedagogy offers powerful opportunities to both acknowledge and actively support the union of theory and practice with the goal of positive change. Just as Pabón-Colón (n.d.) argues for the importance of understanding and appreciating “feminism as a verb, as an action” (Zipp, 2018, para. 3), Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007) and Merriam & Tisdell (2016) make powerful arguments for the value of mixed-methods research for all researchers interested in positively impacting human life, whether through applied social science, education, human-centered, and/or feminist research, lenses, and perspectives (or otherwise).

In Feminist Approaches to Mixed-Methods Research, Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007) explore how feminist researchers are using mixed methods and the relationship between mixed methods research and feminist knowledge building. They write,

Feminist researchers have long been discussing women’s multiple ways of knowing and the multiple sites of vision on which women come to know the world at large. Reasons to break down and avoid the false dichotomy between qualitative and quantitative methods include feminist disciplinary goals that aim to avoid hierarchies and unearned privileging of quantitative methodologies. (p. 276)

Furthermore, elaborating upon the benefits of and possibilities associated with qualitative research for feminist researchers, Leckenby and Hesse-Biber note,

The types of questions asked that fit into a survey framework simply do not capture the issues that you want to understand. Due to some of these limitations found within quantitative methods, feminist researchers have been an integral force in exploring new qualitative methods that avoid the pitfalls of survey research. (p. 251)

Leckenby and Hesse-Biber focus on applications for feminist knowledge building. However, I believe the forces described in their writing have value far beyond research conducted on (or by) feminist researchers (and others actively engaged in movements to end sexist exploitation and oppression and reverse long-standing patriarchies), to include anyone with an interest in “the construction of new knowledge and the production of social change” in “interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary” ways (Brayton, Ollivier, & Robbins, n.d., para. 3) as well as anyone with an interest in better understanding and impacting in positive ways people’s everyday lives and concerns (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016, p. 1) and in higher education, in particular.

When conducting mixed methods action research, it is critical to reflect on important questions associated with the quantitative components of the research and its relationship with feminist digital pedagogy. For example, Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007) highlight, for research with and without a feminist focus or lens, important cautions. Noted cautions include, in part, concerns for “tightly knit boxes of moral judgment” (p. 253) offered in connection with survey research on premarital sexual behavior, and which might, as an example, mirror in some ways the “good/bad dichotomy” mirrored in survey questions on instructor efficacy and implications that how one answers is reflective of whether they are a good or a bad teacher. These concerns are compounded when considered in the context of contingent workers and adjuncts who are oppressed within the system of Higher Education.

As Efron and Ravid (2013) explain, a variety of strategies yield a variety of information types. Moreover, a variety of data sources and types strengthen the ability of a researcher to compare, contrast, and analyze collected data. Additionally, associated triangulation is important as a way to further ensure research validity (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). However, issues of survey selection and quantitative data collection are often replete with choices and alternatives (Choi & Pak, 2005). Adichie (2018) writes eloquently on the importance of choice in feminist theory, and the implications of choice more broadly (especially when a selected survey instrument can ultimately impact policy decisions that impact day to day lives) cannot be understated. Researchers of all kinds and backgrounds can benefit from being mindful of the range of potential biases, both explicit and implicit, that might be fed and fueled in connection with any particular study design. Applying and adopting a feminist orientation to mixed-methods action research promotes intentional and ongoing reflection and related emphasis on choices least (or less) likely to embody “tightly knit boxes of moral judgment” in the ways Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007, p. 253) describe.

As noted, in the referenced action research study, I collected quantitative data in the form of numerical data from self-administered survey questionnaires. This data (collected from adopted self-efficacy survey instruments, all of which had been tested for both validity and reliability with the associated goal of study quality) was used to examine possible cause-and-effect relationships as a result of the study intervention. Collectively, through both quantitative and qualitative methods, I tested the effect of the planned intervention (a web-based collaborative comment bank) on online teaching self-efficacy, collective efficacy, perceptions, and attitudes of a group of participating online instructors.

The adopted data collection methods and associated data analysis demonstrated phenomenological qualities through a process of “ferreting out the essence or basic structure of” an experience, which in this case involved what can be described as the essence of the grading and feedback processes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016, p. 227). Adopted data collection and related data analysis methods also illustrated heuristic inquiry qualities where the “researcher includes an analysis of his or her own experience as part of the data” (p. 227). Finally, adopted data collection and related data analysis methods also exhibited qualities of imaginative variation through intentional and sustained efforts to assess the study’s focus from a variety of perspectives.

Bias, Mistaken Assumptions, and Silenced Voices

“When we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard or welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.” – Audre Lorde (Baker, 2020)

In Intent and Ordinary Bias: Unintended Thought and Social Motivation Create Casual Prejudice, Fiske (2004) notes that “[u]ethical behavior, bias in particular, depends on both motivation and cognition” (p. 118). In all actuality, everyone is capable of behaving badly and making poor judgments. As Fiske (2004) writes, despite “this comfortable account that isolates the problem in a few bad individuals, the accumulated evidence suggests that most of us are perfectly capable of behaving badly, in the relevant context” (p. 119). Judgment is everywhere, including within the survey tools we often use, promote, and distribute in the interest of conducting research to help a surveyed population. Choi and Pak (2005) note that “[b]ias is a pervasive problem in the design of questionnaires” (para. 2). Sadly (yet realistically), the types of bias are many. For example, Choi and Pak identify and describe 48 common types of bias in questionnaires.

So, while feminist researchers are most typically “epistemologically and methodologically attuned to issues of power, difference, voice, silence, and the complexities of the knowable world” (p. 253), all researchers – whether or not they identity with feminist perspectives or lens – can benefit from a deeper focus on these same issues. In preparation for the referenced action research study, I reviewed a variety of efficacy survey tools. It is important to note that there are many such tools and even for survey instruments that present with supporting attestations regarding validity and reliability, interpretations can vary. For example, questions on excellent jobs, meaningful learning, important work, and/or doing well or succeeding in school, as examples, remain subject to interpretation. This possible ambiguity is not unlike that voiced by Adichie (2015) when noting “I often make the mistake of thinking that something that is obvious to me is just as obvious to everyone else” (p. 14). Similar, as well, to Leckenby and Hesse-Biber’s reminder that “[a]s a feminist, you are interested in what is left out when the question is framed as such” (p. 251).

Persistent wonderings and questions regarding the possibility that quantitative survey instruments have the potential to leave some voices silenced finds voice and comfort in the work of Leckenby and Hesse-Biber (2007) and in mixed methods action research more generally. Related concerns for bias, mistaken assumptions, and silenced voices in quantitative survey instruments are another value of mixed-methods action research. Importantly, “mixed methods can access subjugated knowledges and silenced voices” (p. 276) and Leckenby and Hesse-Biber’s work not only makes the case for doing so in connection with feminist research but also in connection with any research, including action research, involving possibly oppressed groups.

Given this reality, ongoing reflection was used to maintain a critical perspective and also to sustain awareness of positionality and possible bias throughout the entirety of the described research study. An intentional process of active and ongoing reflection was relied upon to reduce bias (both explicit and implicit) as much as possible. As one example, the survey instruments I adopted for the study’s quantitative data analysis were modified in ways that were inclusive of all gender identities.

Throughout the entirety of the study, I was simultaneously both a teacher and a learner, and as a teacher/learner I was also simultaneously a researcher. For example, I taught online courses similar in both instructional design and curricular content to courses taught by participating faculty. In this role, I needed to remain aware of the many types of implicit biases that could impact and influence any comparisons or evaluations of instructor feedback across similar courses. Similarly, I actively monitored my own beliefs regarding what qualifies as “quality”, “meaningful,” and/or “personalized” feedback, for example, based on my own experiences (past and present) as a learner. Analogous efforts were applied and sustained in connection with my interpretations of existing research and literature. My positionality also evolved overtime, as my familiarity with participating instructors and the assessments adopted in their individual courses increased over time.

Herr and Anderson (2015) describe a variety of positionality types and categories which to include insider, insider in collaboration with other insiders, insider(s) in collaboration with outsiders, reciprocal collaboration, outsider(s) in collaboration with insider(s), and outsider(s) studying insider(s). Additionally, and importantly, there are a variety of useful ways to consider positionality (Herr & Anderson, 2015). For example, Collins (1990) describes an outsider within to capture the unique experience her race and gender permit. While I identify as female, study participants included fourteen males and four females. In many of the informal conversations and virtual meetings that took place at various points throughout the study, I was the only female. In these contexts, I might also be considered an outsider within as described above.

At all points in a research study, a researcher must both actively reflect upon positionality as a continuum and also intentionally consider where they might fall on such a continuum (Herr & Anderson, 2015). Relatedly, a researcher must also remain aware of the possibility that positionality can change throughout the course of the research process (Herr & Anderson, 2015). Importantly, not only is positionality not static, there are related risks associated if one views positionality in a static way.

My experience presented no exception to this rule and, as my study and its associated term and schedule progressed, my relationship with study participants changed, as well. For example, professional development webinars and informal conversations that occurred at various points throughout the study led to a variety of changes in relationships and interactions with study participants. Given the extended period of time during which the study took place, my relationships with study participants whom I did not know personally before the study commenced evolved and grew as the study’s timeline continued. These changes inevitably impacted, in a myriad of ways, the nature and extent of what participants shared and related positionality, as well. Reflection and journaling provided opportunities to deepen my own understanding of these sometimes subtle changes, and simultaneously heightened my ability to remain aware of their potential impact.

Journaling was especially effective as a tool to both preserve and memorialize insights and detailed experiences conveyed through unique descriptions and language and, ultimately, led to deeper appreciation of the noted changes. The changes themselves were also revealing and suggestive of the benefits of extended time frames when conducting research of this nature. For example, as the study progressed my journals reflected a stronger voice on the part of participant input as well as much richer descriptive detail in participant conversations and reflections. Description and reflection on the part of participants also demonstrated and revealed increased momentum as the study progressed and my journals were helpful in terms of both identifying and documenting these trends and changes.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I explored the potential for mixed methods actions research from a feminist lens to expand feminist knowledge building in the context of online higher education programs, curriculum, and instruction, in particular grading and feedback processes. In doing so, I also examined how an intentionally designed digital tool (a open-access, web-based comment bank) might be incorporated into a broader feminist-based research inquiry to both further promote and support feminist pedagogy and thinking. I reflected on the complexity of feminist oriented mixed methods action research, focusing on issues of choice of methods, bias, reflexivity, assumptions, and voice based on a study I conducted on the web-based comment bank. Study results were both highly positive and promising and yielded positive insights and feedback from participants and related data analysis. I hope these findings as well as the related critical reflection incorporated throughout this chapter lead to more work and collaboration in this area (and in open education and pedagogy more generally), continued growth and use of the open-access comment bank, as well as more interest in mixed methods action research from (and for the benefit of) a feminist lens going forward.

Going forward, the comment bank can further be developed with students too. My hope is that students, with encouragement, will “intervene in the creation of meaning and distribution of power” (Golden, 2018, p. 43). This demonstrates how feminist digital pedagogy can simultaneously have both a “public function” and support work toward decentralization of power and authority structures (p. 42).

The lessons of feminist approaches and feminist oriented critical analysis to mixed-methods action research are powerful and applicable to educational research and arguably all social science research so as to simultaneously access and explore spaces, including educator experiences, that quantitative research alone cannot. That is, while mixed methods action research is not, in and of itself, feminist in nature, this chapter’s work to explore and reflect upon ways feminist researchers might critically evaluate, incorporate and apply mixed methods is broadly relevant and valuable, including in connection with research on online teaching, online grading, online feedback processes, and related instructor efficacy (both self and collective). I hope that these discussions continue and also that the points shared in this chapter help further (and further elevate) related conversations and awareness on behalf of more individuals.

This action research also serves as a reminder of the power of critical reflection on the far-reaching benefits of feminist approaches to mixed methods action research and feminist digital pedagogy, in particular. A related reminder to look ahead points, broadly, towards more supportive and more widely embraced feminist thinking for the benefit of everyone (hooks, 2015), including and perhaps especially for digital tools and instructional interventions and within online learning spaces. Just as “[f]eminists are made, not born” (hooks, 2015, p. 7), so are, I believe, researchers and feminist digital pedagogies. Research and critical reflection on feminist digital pedagogies in practice, and in its many forms, offer guidance for the further growth and development of both.

Endnotes

1. Note that while action research and design-based research share many similarities in their work to both identify real-world challenges and then take action to address and improve those identified challenges, there are also important differences between the two approaches. In particular, unlike action research, a primary goal of design-based research is the generation of theory to solve real-world problems. Additionally, whereas practitioners typically initiate research in action research, it is researchers who typically initiate the design-based research process (Peer Group, 2006).

2. Mixed method research: where a study’s research questions are examined using a combination of both quantitative and qualitative data.

References

Adichie, C. N. (2015). We should all be feminists. London: Fourth Estate.

Adichie, C. N. (2018). Dear Ijeawele: A feminist manifesto in fifteen suggestions. Fourth Estate.

Altman, J. & Leeman, D. (2020). Soul, authenticity and compassion: Essential ingredients in designing meaningful learning experiences. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Baker, B. (2020). 50 Audre Lorde quotes on intersectionality and redefining ourselves. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-NIy

Beunen, R., van Assche, K., & Duineveld, M. (2013). The Importance of Reflexivity in Planning and Design Education. Working Papers in Evolutionary Governance Theory. Wageningen: Wageningen University. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-RrBv

Bond, (2019). Reflections on forming a virtually feminist pedagogy, Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-RJxc

Brayton, J., Ollivier, M., & Robbins, W. (n.d.). Introduction to feminist research. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-pMiL

Choi, B. C. K., & Pak, A. W. P. (2005). A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Preventing Chronic Disease, 2(1), A13.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Crawley, S. L. (2008). Full-contact pedagogy: Lecturing with questions and student-centered assignments as methods for inciting self-reflexivity for faculty and students. Feminist Teacher: A Journal of the Practices, Theories, and Scholarship of Feminist Teaching, 19(1), 13-30.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Deller, J. (2019). How to Evaluate Training Effectiveness in 4 Simple Steps. Kodo Survey. Retrieved from https://kodosurvey.com/blog/how-evaluate-training-effectiveness-4-simple-steps

Ebel. R. L. (1980). Survey research in education: The need and the value. Peabody Journal of Education, 57(2), 126-134.

Efron, S. E., & Ravid, R. (2013). Action research in education: A practical guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Fiske, S. T. (2004). Intent and ordinary bias: Unintended thought and social motivation create casual prejudice. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 117-127.

Gay, R. (2014). Bad feminist: Essays. Harper Perennial.

Golden, A. (2018). Feminist Digital Pedagogy. Virginia Woolf Miscellany, 93, 42–43.

Hattie, J., & Clarke, S. (2019). Visible learning feedback. New York, NY: Routledge.

Herr, K., & Anderson, G. L. (2015). The action research dissertation: A guide for students and faculty. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

hooks, b. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Cambridge, Mass.: South End Press.

hooks, b. (2015). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jorgenson, J. (2011). Reflexivity in Feminist Research Practice: Hearing the Unsaid. Women & Language, 34(2), 115–119.

Klehr. M. (2012). Qualitative Teacher Research and the Complexity of Classroom Contexts. Theory into Practice, 51(2), 122–128.

Leckenby, D., & Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2007). Feminist approaches to mixed-methods research. In S. N. Hesse-Biber & P. L. Leavy (Eds). Feminist research practice: A primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Milanés, C.R. and Denoyelles, A. (2014). Designing Critically: Feminist Pedagogy for Digital / Real Life. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-AvGY

Pabón-Colón (n.d.). Feminism is a verb. Retrieved from https://jessicapabon.com/

Peer Group (2006). A PEER tutorial for design-based research. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-AWDc

Reinharz, S. (2011). Observing the observer: Understanding ourselves in field research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching more by grading less (or differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159–166. doi:10.1187/cbe.cbe-14-03-0054

Schneider, J. (2020). On matters of feedback: Supporting the online grading feedback process with web-based, collaborative comment banks (Order No. 28151360). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (2503663917).

Taylor, S. (2016). The evidence of “ordinary” people? [Youtube]. National Centre for Research Methods. https://edtechbooks.org/-UnW

Tierney, J. (2013). Why teachers secretly hate grading papers. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-Pbb

van Ewijk, R. (2011). Same work, lower grade? Student ethnicity and teachers’ subjective assessments. Economics of Education Review, 30(5), 1045–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.05.008

Zipp, M. (2018). Feminism, Graffiti, Gender Fluidity: An Interview With Jessica Pabón-Colón, author of Graffiti Grrlz. Retrieved from https://edtechbooks.org/-dyPk