As you put together your initial reference base, plan your inquiry processes, carry out your research or project, and begin analyzing and verbalizing what you have learned. You are continually moving across research territory that others have already claimed. You need to navigate and negotiate very carefully. You must appropriately acknowledge the contributions of others (and do so in proper format), but you must allow and credit the contributions of your own mind. As you gain ideas of your own, you need to compare, contrast, and develop them in the context of the work of others in order to develop maximum strength and effectiveness. And while you are doing all this, additional hurdles keep coming up, as you must handle a good number of new conventions and formats.

This chapter focuses on the tricky business of managing that trail consisting of the articles, books, papers, presentations, and additional work of other researchers, a.k.a using and citing references correctly, accurately, and ethically. It begins with a discussion of why referencing the works of others is such an important aspect of professional participation. If you understand why, then when, where and how will probably fit into place fairly easily, and these are discussed as well.

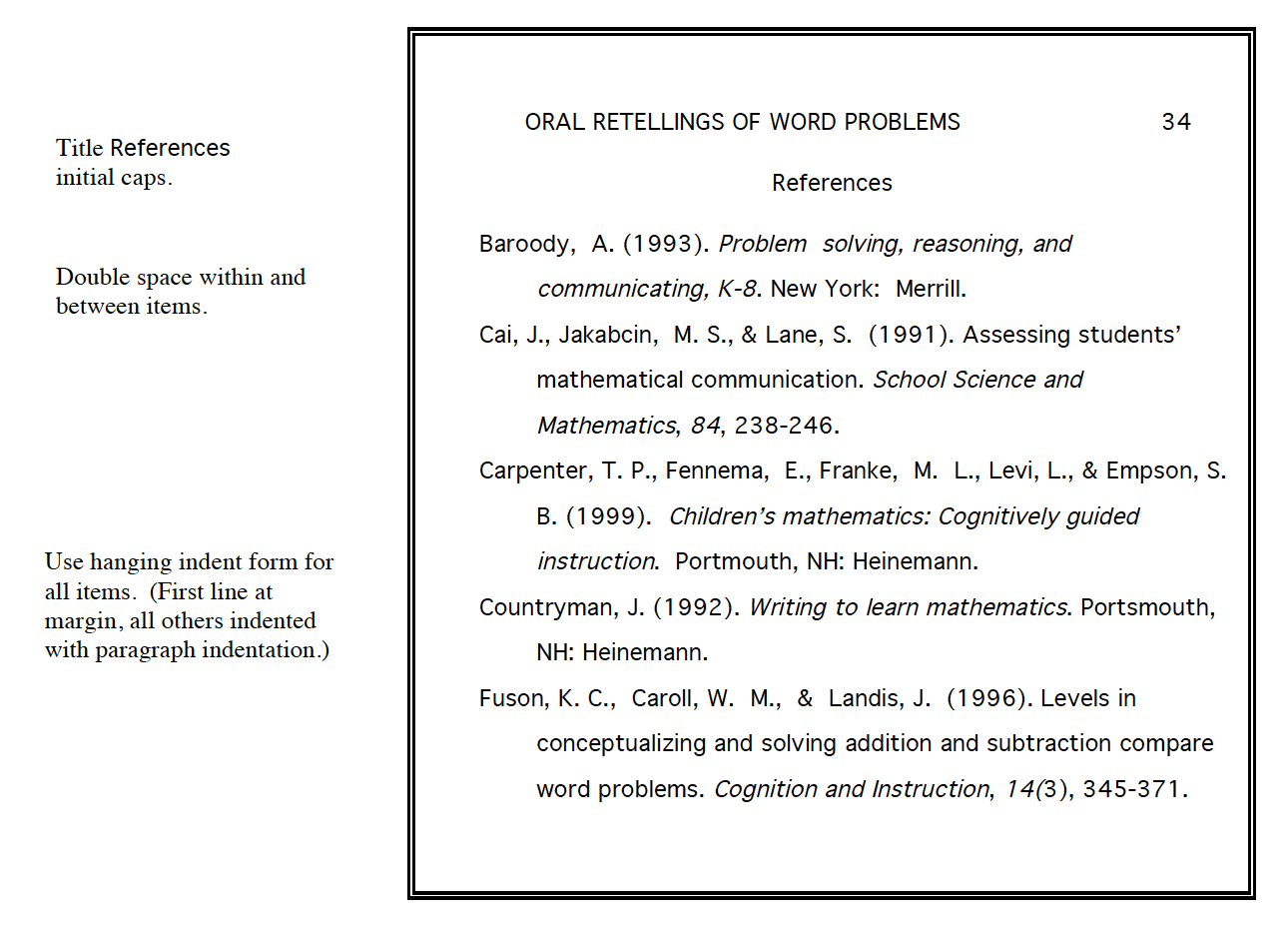

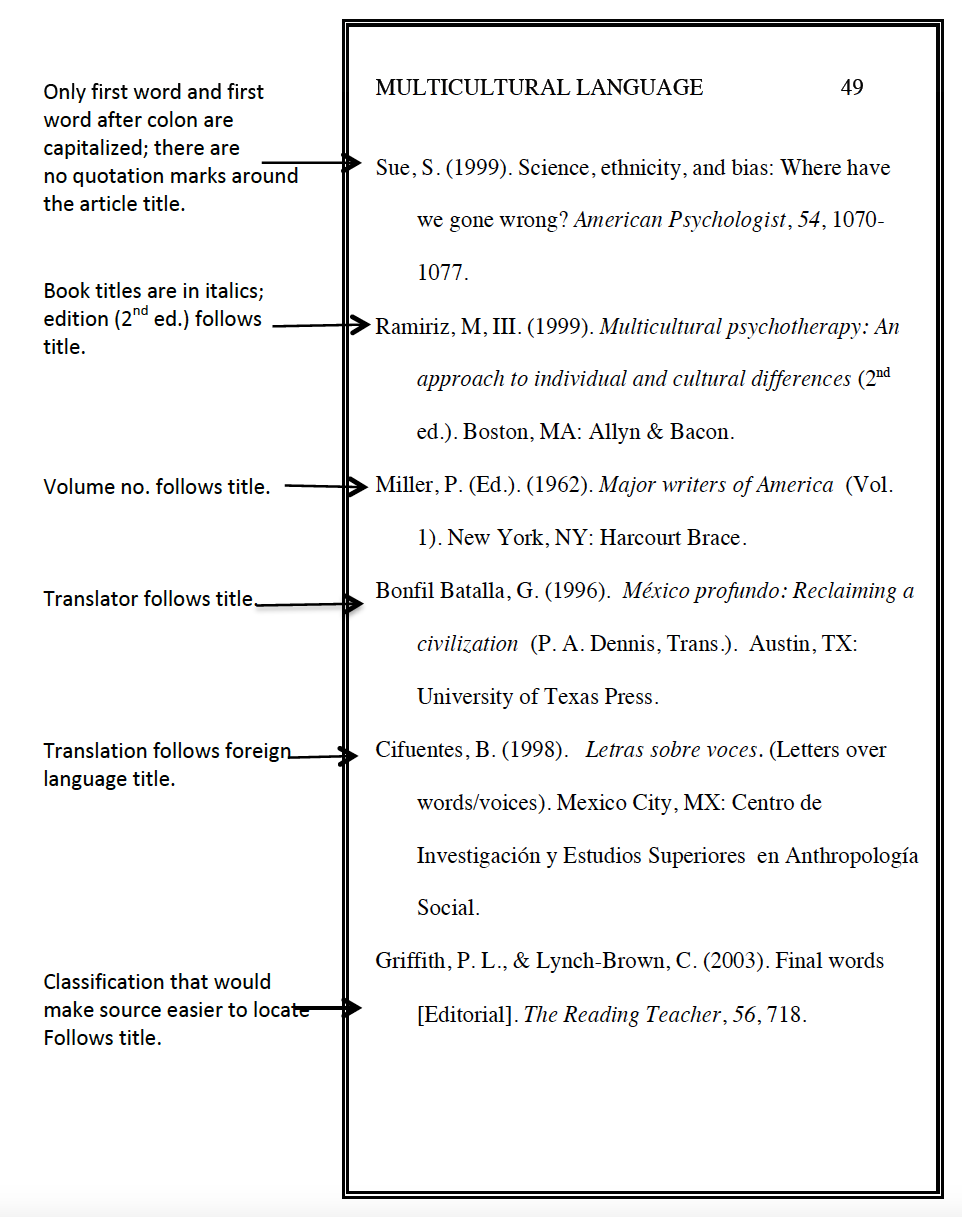

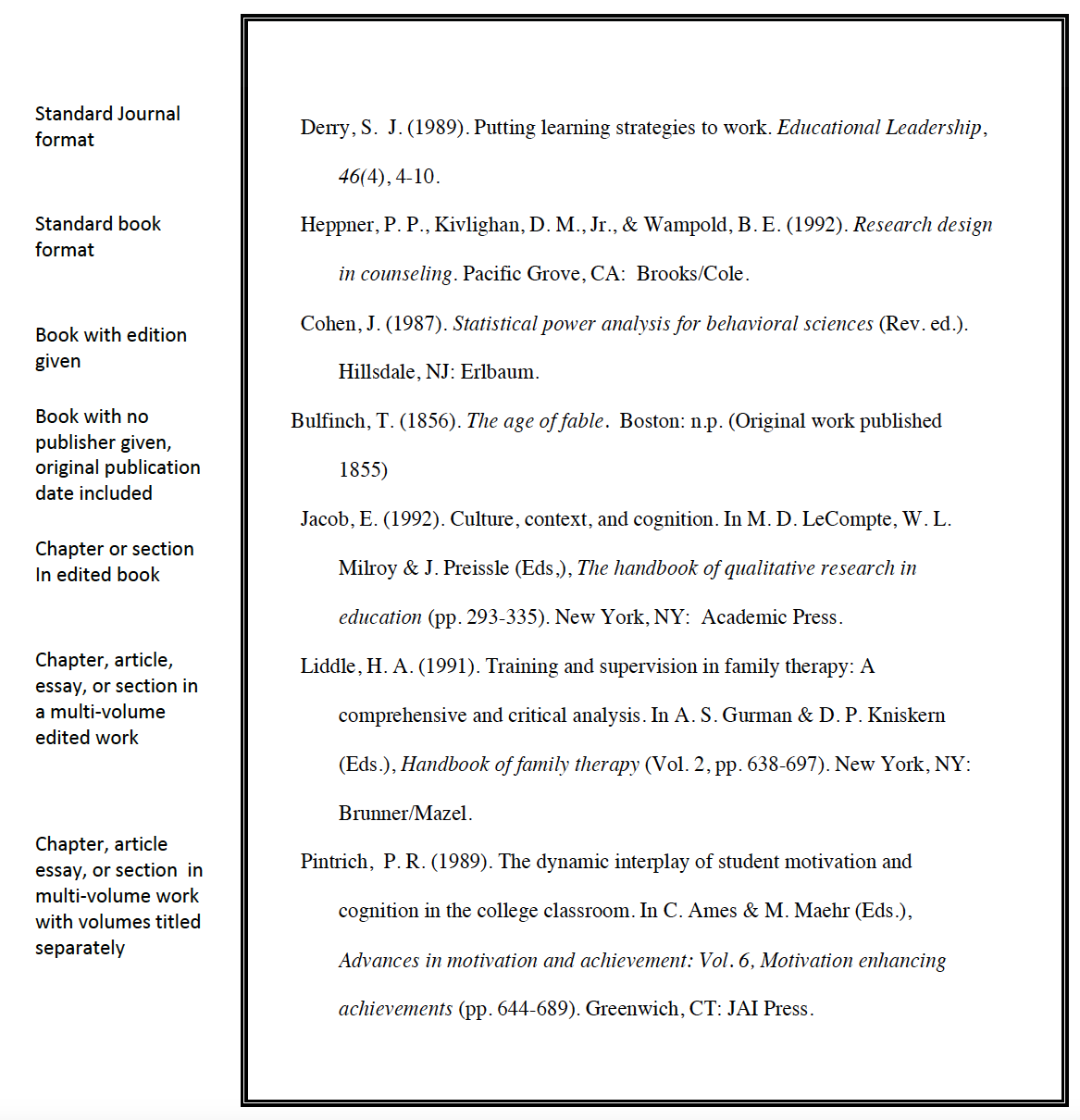

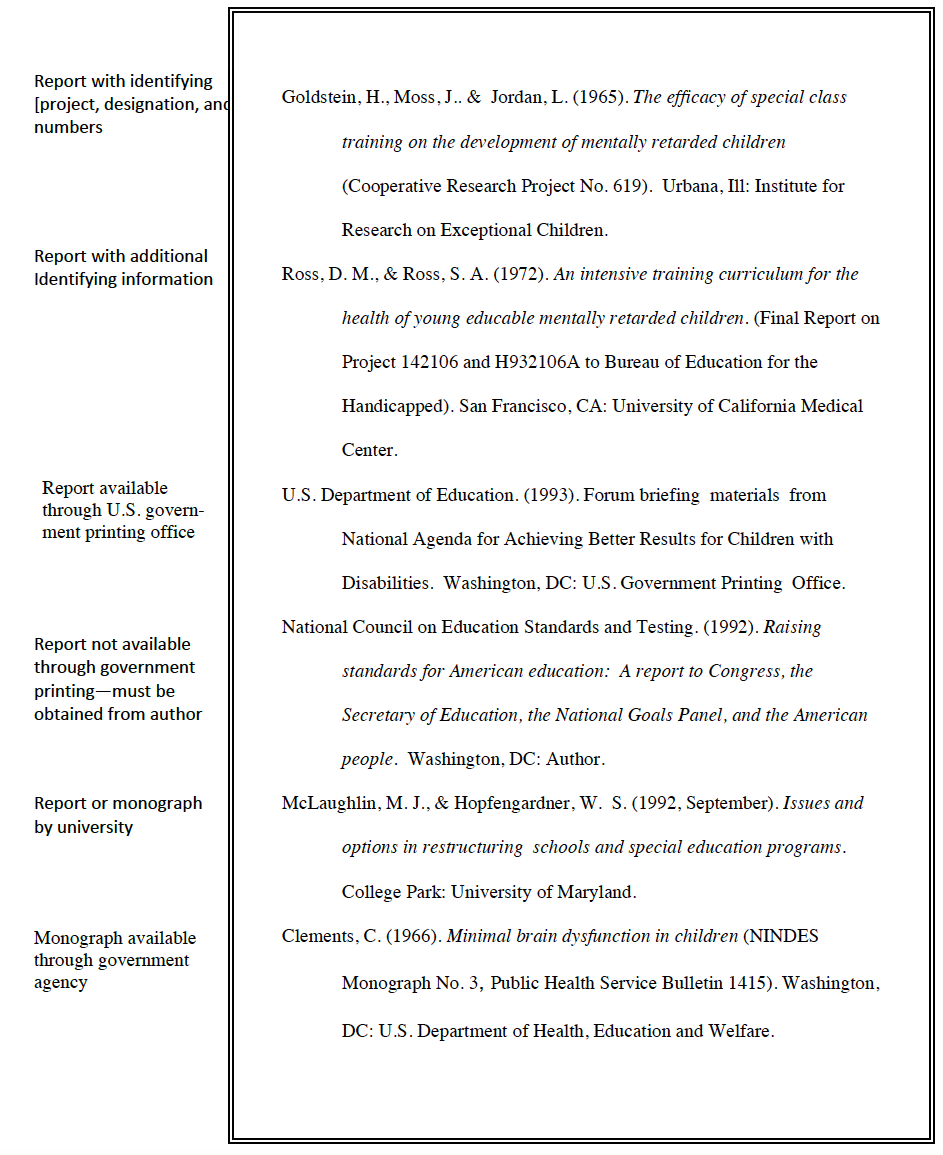

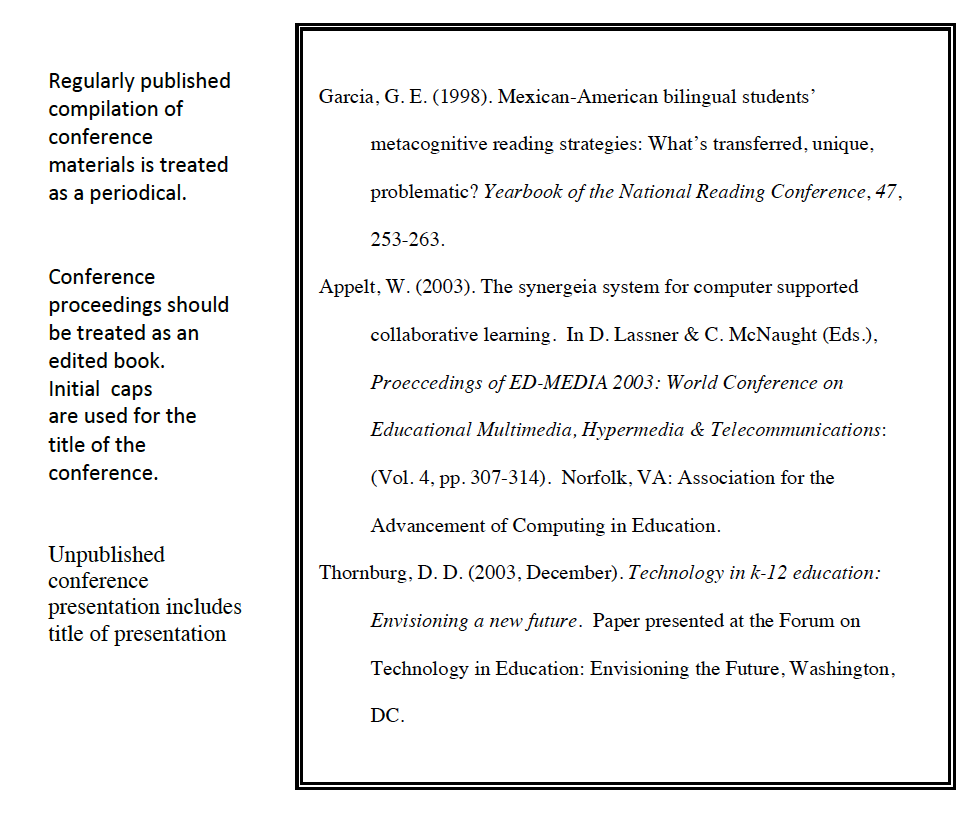

The many components, contexts, and details of reference list format can seem a little overwhelming. Nobody I know has the entire lot memorized. However, the process of putting the reference list together can become a little easier if you get some general patterns down and only have to look up the exceptions. This handbook will not include all the rare exceptions, but you can easily find them in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2010) or on one of several web sites, including Purdue’s OWL (Online Writing Lab).

Why Cite?

If you were presenting a musical program for which you had written some of the pieces, you wouldn’t merely perform piece after piece as if you had written them all. Similarly, if you were displaying the works of other visual artists along with your own at an exhibition, you would carefully indicate the borrowed works with full credit for their creators. To imply that you had produced artistic works created by others would be blatantly unethical and dishonest. And you would deprive your audience of the benefit of becoming acquainted with other artists who might be of interest to them. In developing your paper, article, thesis, or dissertation, you are in a sense giving a recital or a show. All contributors must be acknowledged, and the audience should learn to appreciate their work as you do.

Reason 1: You Need to Give Credit Where Credit Is Due

Ideas, opinions, observations, research, and data analysis and interpretation are as much the products of creative minds as songs or paintings. Although you may not have picked up your research sources with as much eagerness and fascination as you would a best-selling novel, the author has put a lot of work into that book or article, report, presentation, etc.; a lot of time, and a lot of critical, creative, and—believe it or not—actually imaginative thinking. The researcher has put in as much stress and deserves the same credit for his or her creation as does the composer, sculptor or playwright.

In deciding whether to make a citation to give credit, ask yourself these questions:

- Is this a unique creative work by an individual or group of individuals?

- If all the authors whose works I have consulted were to read my paper, article or dissertation, would they feel that they had received appropriate credit for their ideas and research?

The following types of materials and resources are referenced under the ethical consideration of giving due credit:

- Direct experiences

- Experimental studies

- Case studies

- Observations

- Methodologies or strategies worked out by individuals or groups

- Seminal work on theories or approaches

- Specific applications of theories or approaches

- New directions on theories or approaches

- Conclusions based on research or observations

- Opinions

- A specific list or selection of materials compiled by the author(s), even though items within that selection may be common knowledge

- A metaphor, simile or other image or figure of speech worked out by the author(s), even if the point being illustrated is common knowledge

- Any visual or graphic presentation

- Analysis, discussion, or criticism by the author(s) of the work or research of someone else

- An individual or team’s unique definition of a term

Reason 2: You Need to Let a Reader Know Where to Learn More

Often a patron attending a concert will enjoy a new sound or new style enough to want to hear more of it. A quick glance at the program will provide the composer’s name so that recordings of the specific piece or of others by the same composer can be easily located.

Similarly, a reader encountering unfamiliar information may want to find more concerning that particular idea, approach, theory, line of research, etc. By learning where you found the discussion of these points, the reader will know where to go to learn more.

In every field there is widely known information that can be found in almost any authoritative work on the topic: for example, the observation that illiteracy is a common cause of juvenile crime or the fact that giving stimulant drugs is the most common treatment for children with ADHD. These points may not be well known to the individual on the street, but someone doing research would have no problem locating further information on them. We refer to these points as common knowledge. Something can be considered common knowledge if it could be found in at least five different sources. A reader would not have to go to the source where you found common knowledge points in order to see them validated and discussed. So you do not have to give your source, unless there is another reason for doing so.

In deciding whether to cite a source so that a reader can learn more about the topic, you may want to ask these questions:

- Could a reader find this information easily in at least five different sources?

- Is the treatment you found so complete, authentic, or in depth that a reader would benefit more from reading about it in your source than in others?

- Is the point so new or so innovative that a reader might have difficulty locating information, although technically five sources would include it?

The following types of materials are generally cited so that a reader can use your references in locating further information:

- First-person accounts and other primary sources

- Archival sources: records, logs, journals, files, legislative hearings, legal documents, special collections, etc.

- Very current research

- New theories or approaches

- Particularly in-depth topic examination

- New perspectives or applications

- Literature critiques, reviews, or meta-analyses

Reason 3: You May Need to Give Sources in Order to Fix Responsibility

If concert goers hear a new “sound” and aren’t sure whether they like it, they may glance quickly at the program to see who composed the piece. The credibility of the person who created the new style may well determine how seriously the audience considers it and how favorably they receive it. The same is true of information. If something is new, innovative, or unusual, a reader wants to know right away who takes responsibility for it.

In considering whether a source needs to be cited to place responsibility, you may want to consider these questions:

- Is the topic controversial enough that I need the author’s name to validate the information?

- Is the research innovative enough that the audience needs to have a name they trust in order to give it the consideration it deserves?

- Although the information could be found easily in five sources, do I need to attach a name to it as a way of signaling to the reader that it is not something I necessarily advocate?

The following types of materials are generally cited to place responsibility:

- Personal opinions (although they may be popularly endorsed and thus widely available)

- Conclusions based on personal experiences

- Political ideas, positions, opinions

- Religious ideas, applications and interpretations

- Value judgments stated or implied

- Moral or ethical positions stated or implied

- Controversial topics

- Emotional topics or positions

Reason 4: You May Cite Some Sources to Put Your Ideas in Context and/or to Build Credibility

On most topics there are particular authors whom most researchers working in the area respect and expect. You need to show that you have consulted these widely acknowledged experts, and you need to show how your thinking relates to and is influenced by theirs.

In deciding whether you need to make a citation to build this credible reference base, you may want to consider these questions:

- Will my readers consider this author and/or this work essential to a strong presentation on this topic?

- Does my work provide an extension of or contrast to this work that the readers need to understand? Was this work a basis for my hypothesis or a context for my research?

- Will reference to the work or the author(s) contribute to a framework that will make my work more meaningful or easier to understand?

The following types of resources may be cited to build context and credibility:

- Researchers whose work established an area of inquiry, for example, Bandura, Glasser, Friere, Dewey, Kohlberg, etc.

- Researchers and authors whose work contributed substantially to the development of an area

- Researchers whose development of a topic is so widely known that citing their names may save you a good deal of background explanation

- Researchers currently recognized as prominent and productive

- Researchers whose positions or affiliations lend prestige to a topic

How Do I Cite? How Do I Handle the Citation?

By considering the reasons for documenting your sources, you can understand the importance of working carefully into and out of the information you borrow from them and of being sure that such aspects as authorship and publication availability are handled correctly.

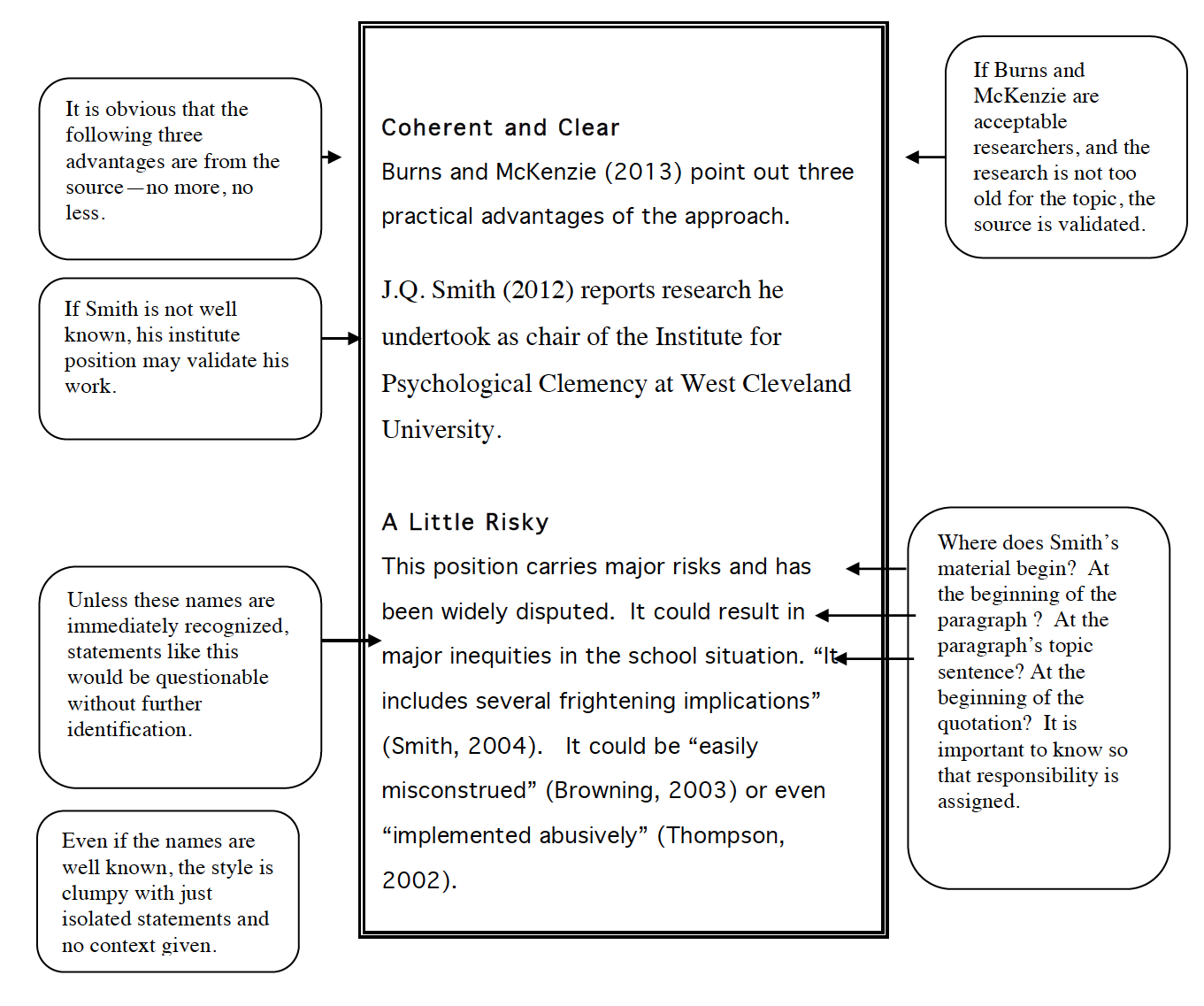

Precaution 1: Handle the Citation so that a Reader can Easily Tell Where Information Taken From a Source Begins and Ends

There are several advantages to introducing the source by author and date as you begin taking information from it:

- You make the beginning of the “borrowing” easy to identify, making clear to the reader what is taken from the source and what is your own comment, analysis, or enhancement.

- The reader knows the author(s) and the date of the research from the beginning and can interpret and assign credibility accordingly.

- For authors who are not well known, you can easily identify their positions or accomplishments to give additional clarity or validity to what you cite.

- Introducing the source leads smoothly and coherently into the borrowing. You avoid the common problem of seeming to plunk in quotations or other points that may not be clearly relevant.

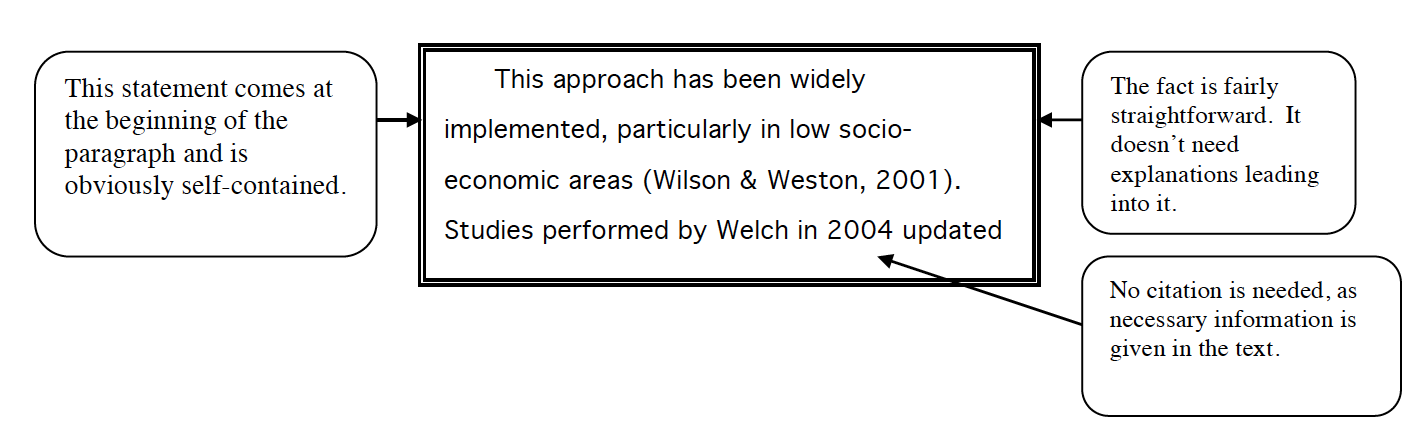

If the context of the cited material makes the parameters easy to discern, citation of both name(s) and date can simply be placed at the end of the borrowing.

Obviously a summary of a study is self-contained, and many opinions and analyses are obviously uninterrupted. In such cases, if the author is well known then acknowledgement at the end may accomplish what your readers need. Using this form of citing when you can may help to avoid the “he said, she said” monotony that characterizes some academic writing.

If both name(s) and date are given in the text, no citation is necessary.

Precaution 2: Be Sure that Everyone Gets Due Credit and Takes Due Responsibility, Not Just the First or the Loudest

If your thesis or dissertation is turned into articles, you’ll want credit, even if you are not actually listed as first author. Be careful to give the same courtesy to other (perhaps fledgling) subsequent authors.

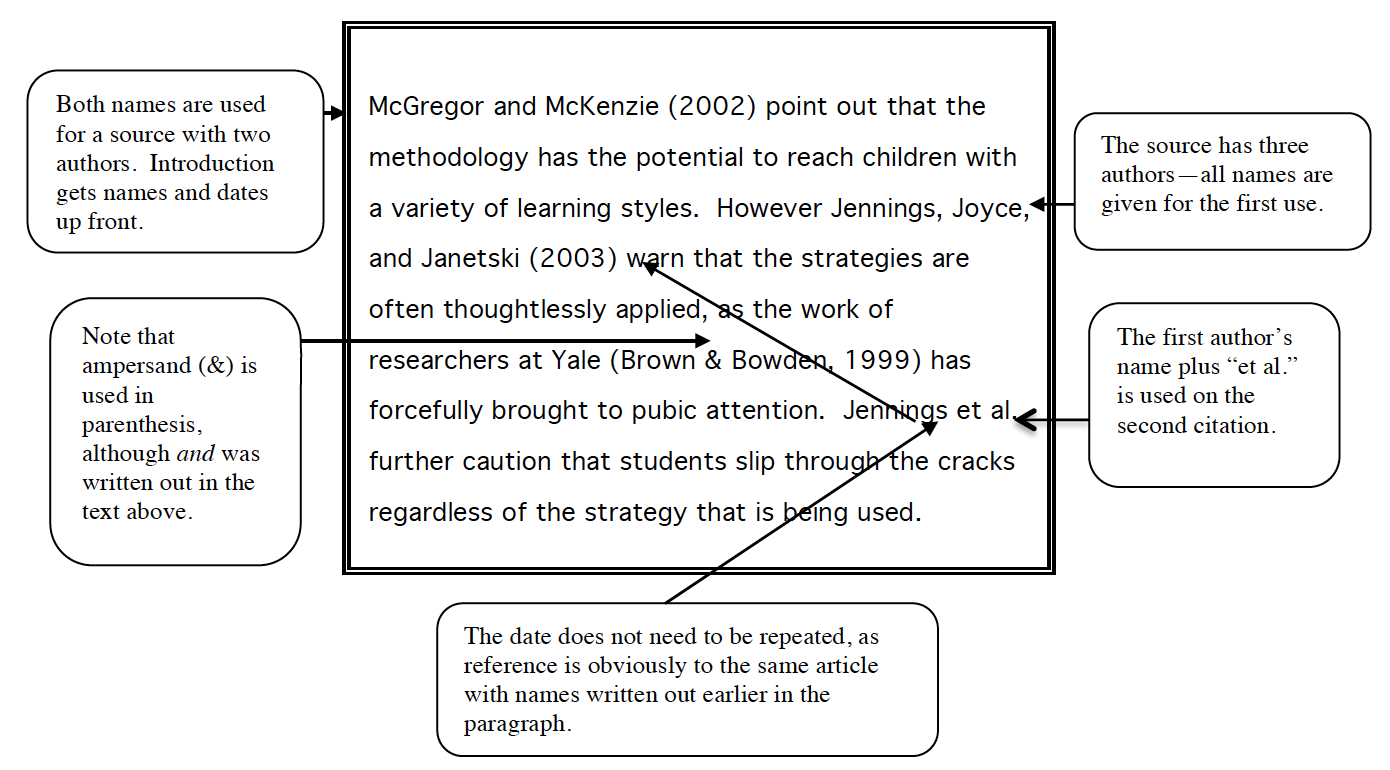

Follow APA conventions for listing multiple authors in the citation.

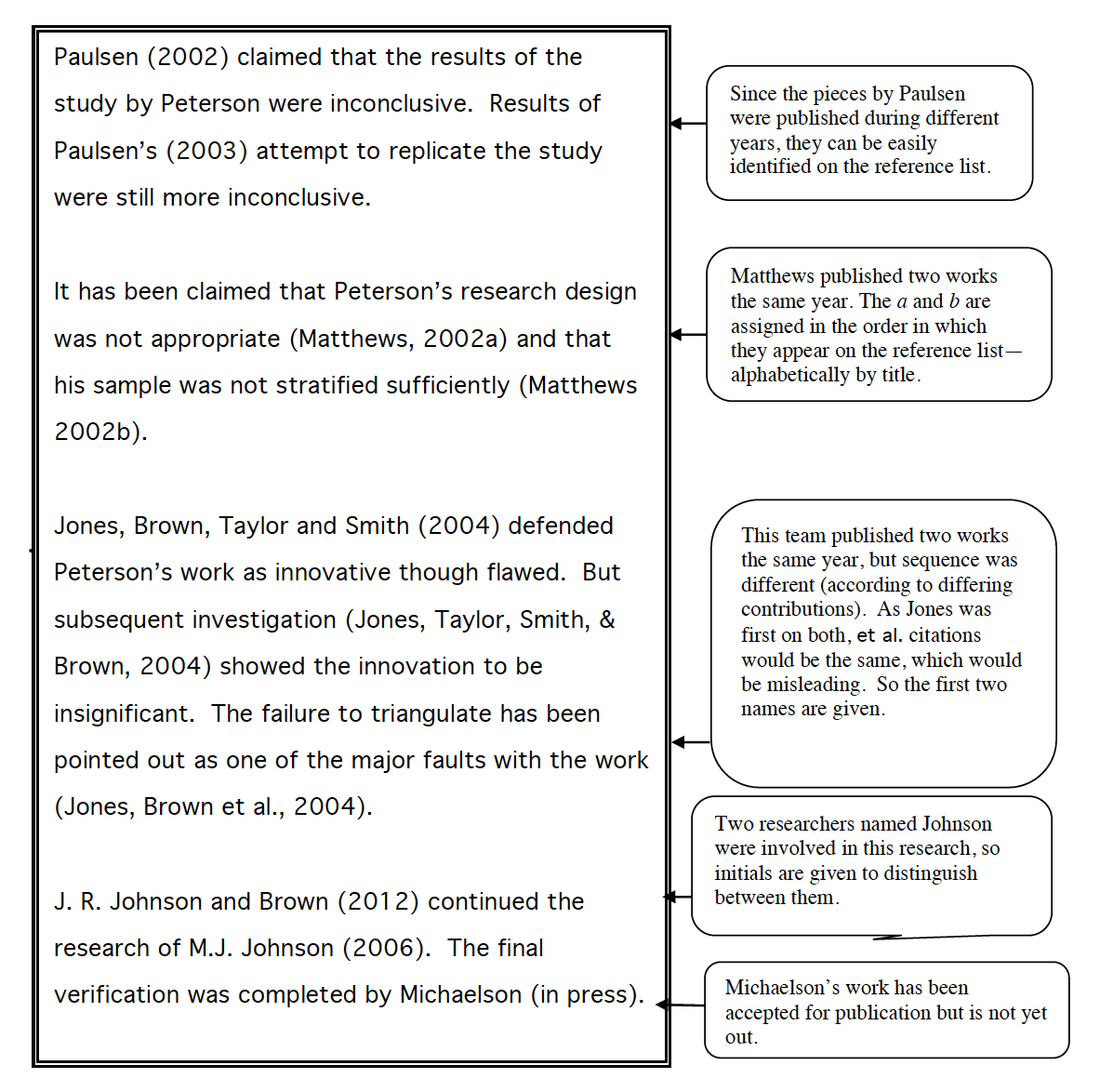

For a source with two authors, give both names every time.

- For a source with three, four, or five authors, give all names for the first use and the name of the first author followed by et al. for subsequent uses (Do not italicize et al. Use period after al.)

For a source with six or more authors, give only the name of the first author plus et al.

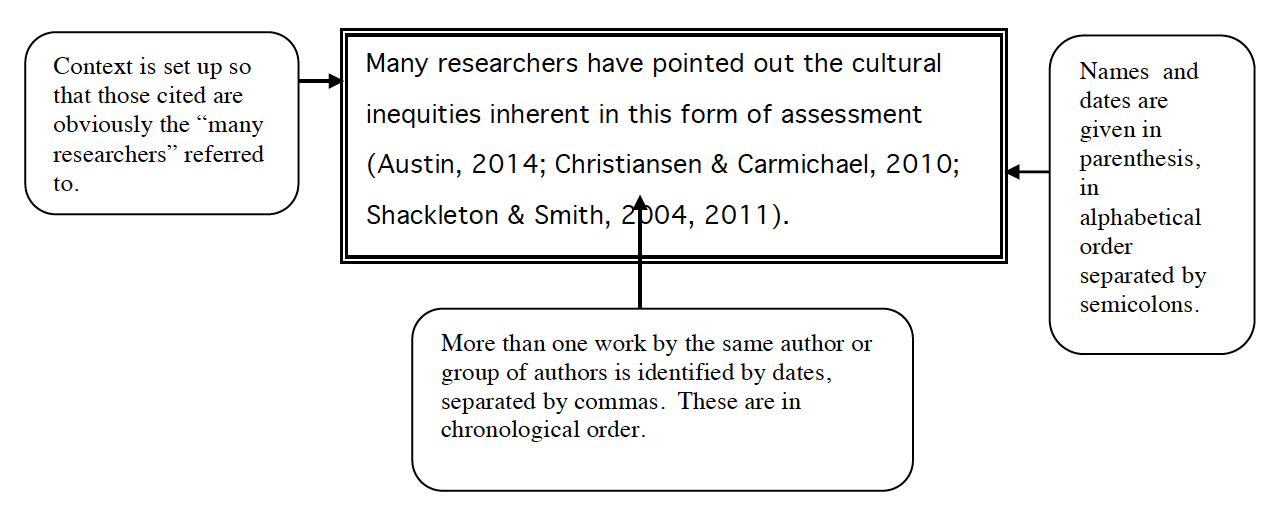

If more than one author or group of authors treats a point that needs to be cited, group the sources in the same parenthesis in alphabetical order.

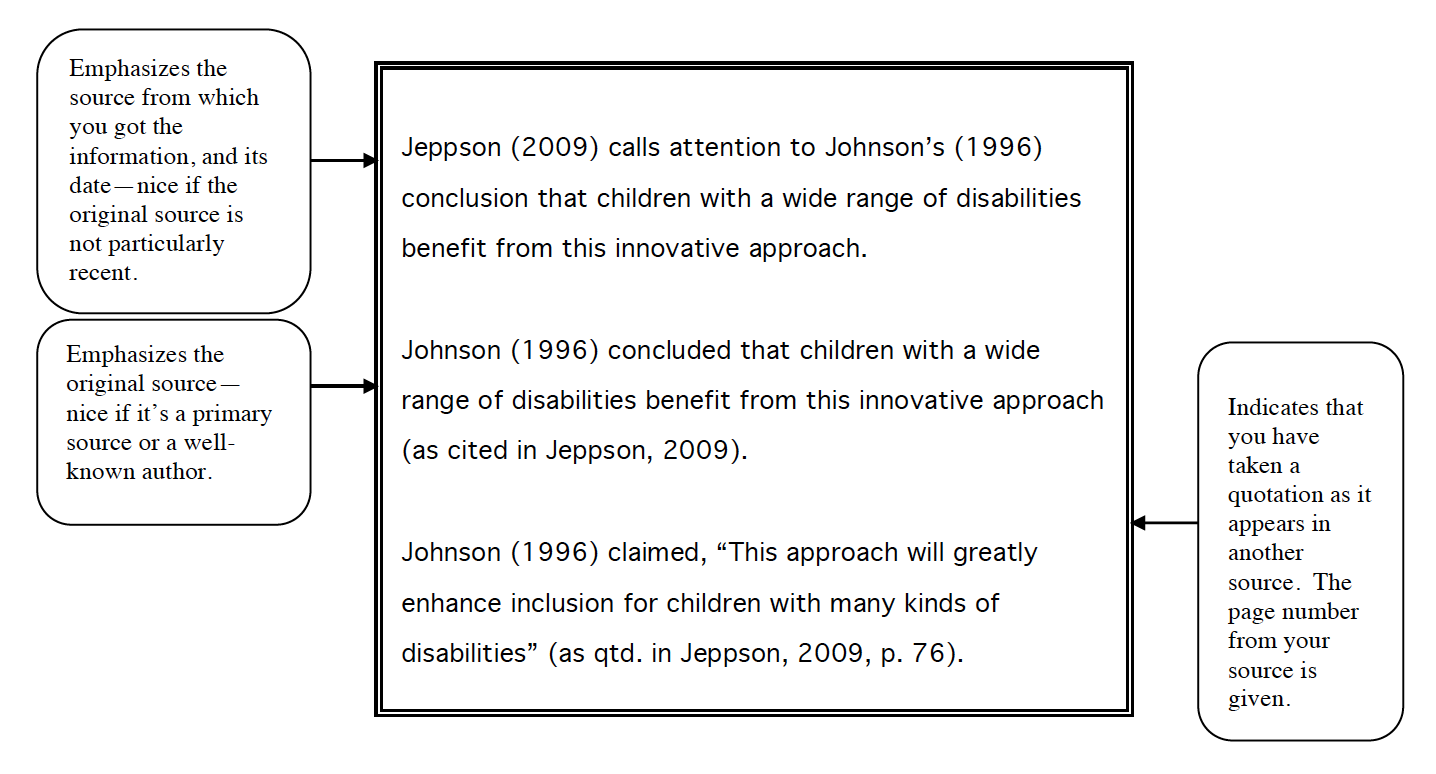

If you are using something cited or quoted by another author and you have not consulted the original source, be sure that you make this clear—for your own protection.

If the author of the article from which you got the information has distorted or misrepresented, he or she is responsible, and you will not get angry calls from the original author berating you for missing the point. Yes, indignant calls have been received when authors have pretended that they have gone to the original when they have not actually done so.

Precaution 3: Recognizing the Nature of Professional Expectations, Be Alert to Multiples and Overlaps

When an author becomes either very knowledgeable or very desperate for tenure or promotion, he or she may produce many book chapters, articles, presentations, etc. very quickly. You need to be sure that your readers can easily find the particular piece that you are citing.

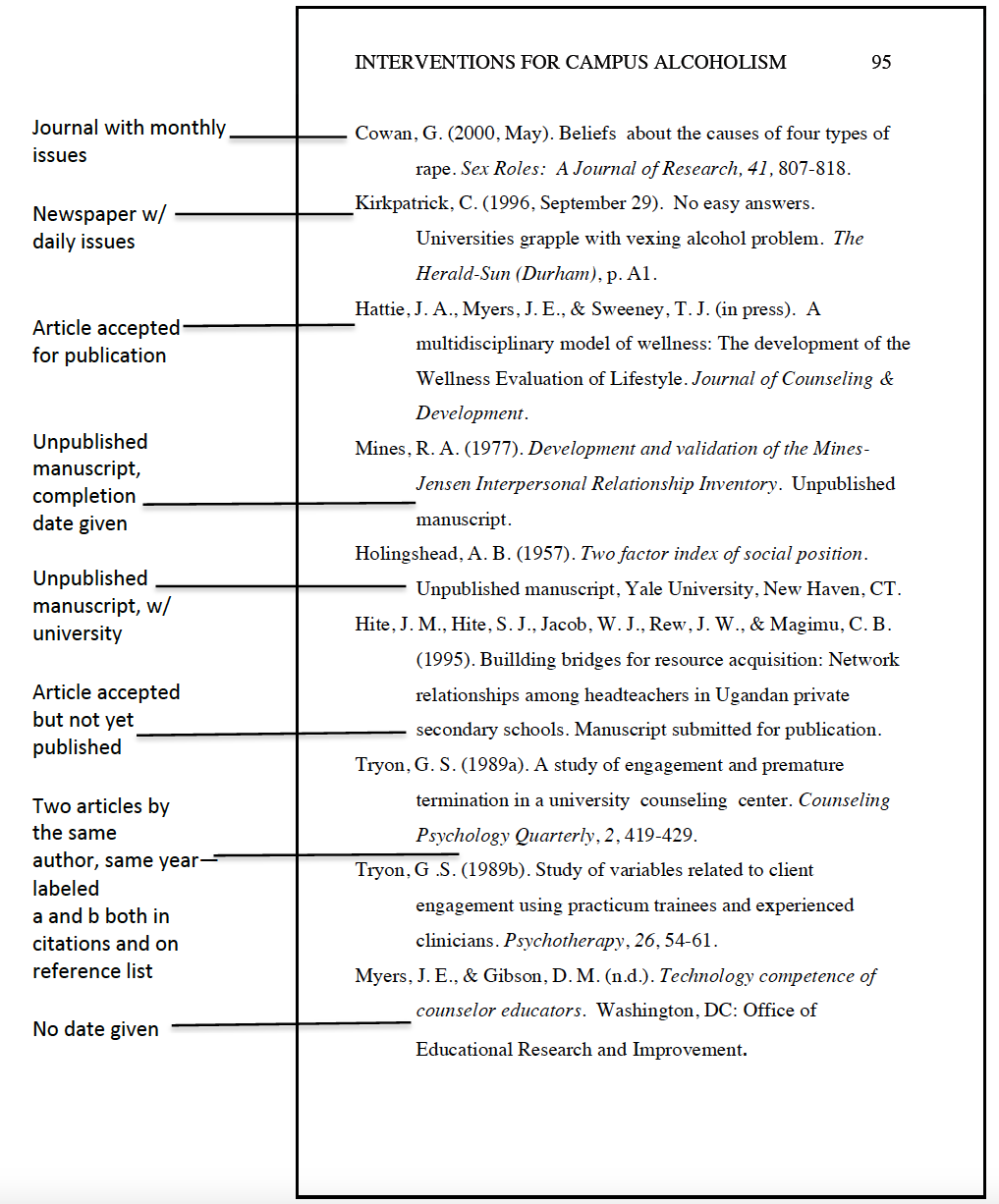

Distinguish carefully between works by the same author or group of authors.

- Multiple works by the same author(s) with different dates will be distinguished by the date.

- Multiple works by the same author(s) the same year are distinguished by adding a, b, c etc. following the date. The letters will distinguish the works on the reference list as well, so they are assigned in the order the works will appear on the reference list—alphabetically by title.

- Always list multiple authors in the sequence the names appear on the title page or byline. If the same group keeps switching positions, be sure you keep the switches straight. If you cite them in a different sequence, then you may be citing a different work.

- If a particular first author heads more than one group publishing works the same year so that two et al. citations come out the same, use the first two (or three if necessary) authors’ names—set off by commas—before et al.

- Jones, Brown, et al. (2002)

- Jones, Smith, et al. (2002)

Differentiate authors with the same surname by using their initials in all citations, even if works were published during different years.

Even (perhaps especially) with well known husband/wife teams, you need to be sure that both names with accompanying sets of initials are given when appropriate.

If something has been accepted for publication but has not yet actually been published, put in press in parenthesis in the date position. If something is in process but has not been accepted, you can use in review, or being revised in the same position. Do not include the date until the work has actually come out.

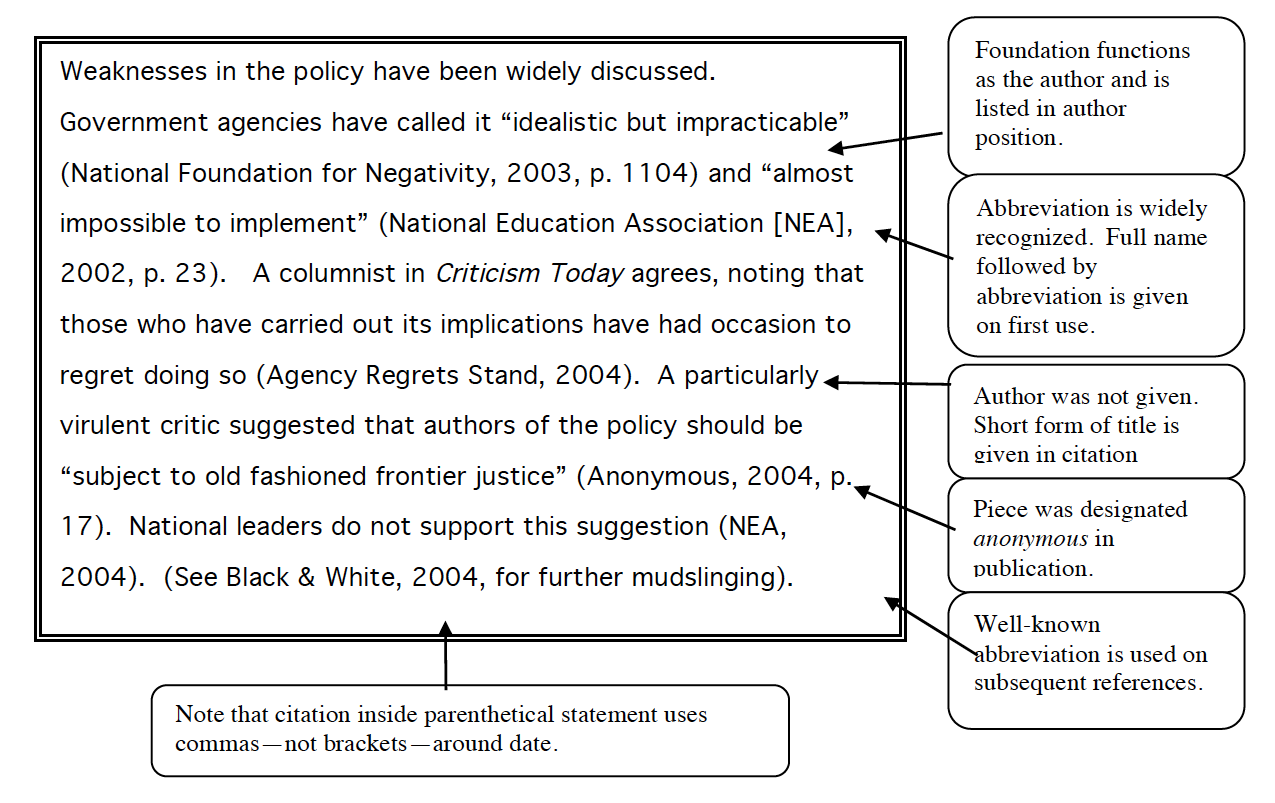

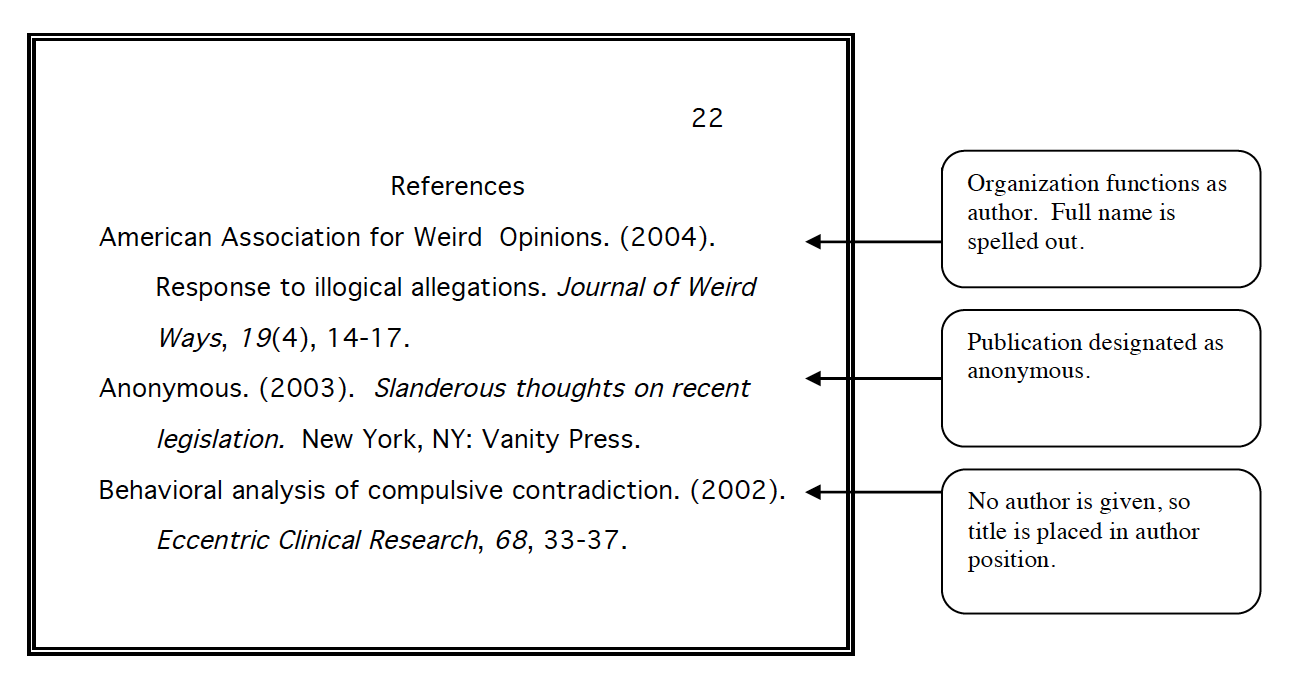

Precaution 4: Remember that Anonymity and Eccentricity are Part of the Profession Too

When an organization is given as the author, put the name of the organization in the author

position.

Spell out the name each time it is used unless the abbreviation is well known and easy to recognize.

For well-known abbreviations, give the full name followed by the abbreviation the first time, then the abbreviation in later citations.

When no author is given, cite by giving a short version of the title—just a few words.

The full title will be used in the author position on the reference list.

When the byline says “anonymous,” then cite “anonymous” in the author space both in the parenthetical reference and on the reference list.

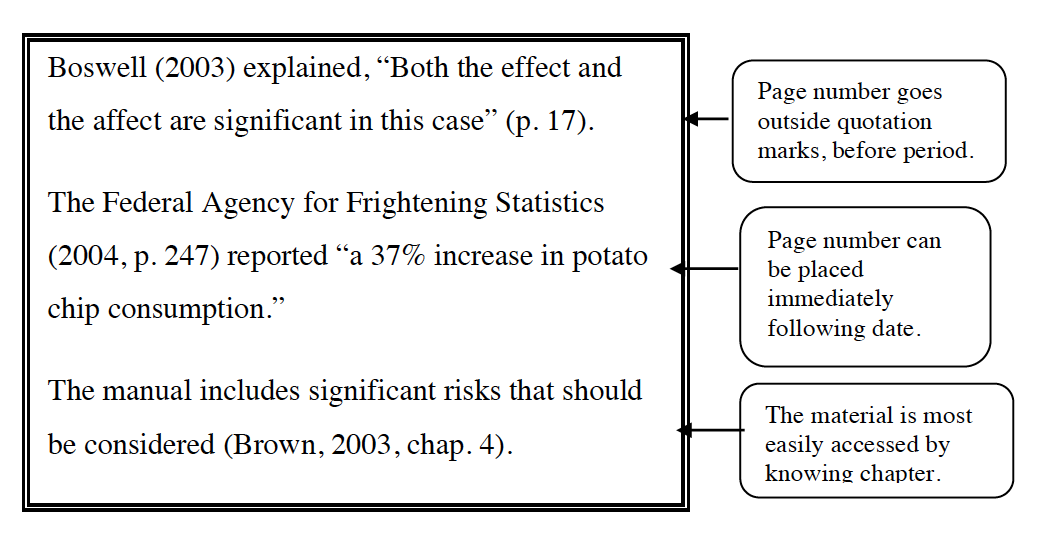

Precaution 5: Give Page or CHapter Numbers for Direct Quotations

Precaution 6: Designate Personal Communications as Such; The Reader Will Just Have to Trust You

Not everything that informs a study or piece of writing comes from a published source. Much is learned from direct personal communication. These materials cannot be retrieved by your readers for close examination or verification, but they still need to be credited if they take you beyond common knowledge. The following may be included in this category:

- interviews

- telephone conversations

- letters or memos

- email

- non-archived electronic discussion groups

Precaution 7. Avoid Leaving Blanks that May Seem Like Something Has Been Forgotten

If you don’t want your professor, graduate committee, or journal editor telling you to go back to the library and track something that cannot be tracked, you need to pass the buck to where it really belongs.

Electronic sources may not give page numbers.

- If paragraph numbers are available, give them—preceded by ¶ or para (Leavitt & Leggett, 2003, ¶ 22).

- If paragraph numbers are not given, give the heading and count the paragraphs from that heading yourself (Zigler, 2004, Discussion, para. 4).

Classical works are in a class by themselves. Often dates and occasionally authors are not known, and other aspects are assumed known or easily accessible.

- For very old works, cite the date of translation, preceded by trans: (Plato, trans. 1942).

- If you know the original publication date as well as the date of the publication you used, give both dates in the citation: (Freud, 1919/1952).

- Major classics (Greek, Roman, Biblical) do not need formal citations or page numbers. Numbers of cantos, verses, and lines of ancient works or of books, chapters, and verses of the Bible are consistant in all editions, so the numbers make text easier to locate than page numbers. Give the edition you are using the first time that you use it: Romans 15:13 (King James Version).

Occasionally publication date is not given. To place the buck where it belongs, give the author with n.d. to indicate “no date” provided (Willliams & Willis, n.d.).

Precaution 8: When a Citation Ends a Sentence, Be Careful to Get it on the Right Side of the Period

With all the questions of ethics and accuracy that are involved with citations, one would think that whether a period comes before or after a citation should be rather insignificant. Unfortunately, it isn’t. Like the number of words in the abstract or the capitalization of words in various levels of headings, it’s a matter of professionalism. You do a thing a certain way because the profession expects it.

With APA format, when the material cited is embedded in a paragraph, the citation comes before the period. The period is considered to be your sentence-ending period, and the citation is part of the sentence.

The study furnished “empirical support for the proposition” (Rosenberg et al., 2004, p. 17).

When a quotation is blocked, the citation follows the period. The period is considered to be part of the blocked quotation (the author’s period, not yours), so the citation is not part of the quoted sentence.

How Do I Handle the Reference List?

Preparing a reference list may feel like navigating an obstacle course, particularly if one has carelessly jotted down information with the idea of dealing with requirements and formats later. Often that “later” is right against the submission deadline, when patience is short and a trip to the library to locate an elusive page number in a returned book can be a major disruption.

Anticipate Needs and Provide for Them

Sometimes forethought can save you from later hassles, particularly if you are not a natural perfectionist and hate having to be a deadline-harassed unnatural one.

You may prepare your reference list as you go along rather than after you finish a chapter (or worse still, after you finish the entire project).

- If you write out each reference as you draft the citation into the text, then you won’t risk leaving one off the reference list.

- You won’t put something into the reference list that is not cited in the text if you only add to the list as you draft in the citation.

- You are less likely to have an inconsistency in the spelling of a name (Peterson/Petersen) or the digits of a date (1989/1998), and you avoid the embarrassing error of citing a page that doesn’t exist (p. 87 in an article that goes pp. 64 to p. 84) if you are dealing with the textual citation and the reference list side by side.

- If you don’t have a program that formats your references for you, it is easier to focus on the format technicalities as you draft rather than later when you’re too tired to think straight.

If advance preparation is not the way your mind works, check these things VERY carefully afterward.

- Items should not be included in the reference list that are not cited in the text.

- The reference list must include everything that a reader could retrieve (personal communications are not listed, even thought they are cited in the text, because a reader would not be able to access them).

- Spellings and numbers must be very carefully checked.

Format the Reference List According to APA Conventions

- Start the reference list on a new page

- Double space both within and between entries

Alphabetize Items on Reference List According to the Surname of the First Author; If Something is Unsigned, Begin with the Title and Alphabetize the Item inot the List by its First Significant Word

In capitalization conflicts, the trend is to simplify.

- Short before extended: Williams before Williamson

- Mc and M’ as they are actually spelled, not assuming they should really be spelled “Mac.”

- Prefixes such as de, du, le, or von as part of the name if they are commonly used as part of the name: DeBry, LeBaron (lesser known prefixes at the end: Beethoven, L. von)

- Numerals as if they were spelled out

When dealing with prolific authors, remember that first comes first.

- More than one solo article—first come, first entered:

- McDonald, R. (2000).

- McDonald, R. (2002).

- Same for combos if names are in the same sequence:

- McBride, J. Q., & McDougall, W. R. (1999).

- McBride, J. Q., & McDougall, W. R. (2003).

- Author(s) up for tenure who publish many the same year and you happen to cite two or more of them—alphabetically by title, designating a, b, c etc. so you can identify which is which in the text:

- MacKenzie, B. B. (2002a). Classroom . . .

- MacKenzie, B. B. (2002b). Writing . . .

- MacKenzie, B. B., & McLean, U. J. (2012a). Inclusion . . .

- Mackenzie, B. B., & McLean, U. J. (2012b). Reading . . .

- First author alone before first author plus friend(s):

- MacKenzie, B. B. (2009).

- MacKenzie, B. B., & MacArthur, W. J. (2007).

- First author followed by different line-ups—first different author determines sequence:

- McDonald, R. N., & LaMont, C. K. (2010)

- McDonald, R. N., McBride, J. Q., & Baird, W. R. (2008).

- McDonald, R. N., McBride, J. Q., & Foster, M. B. (2009)

- Same surname—initials determine sequence:

- McBride, J. Q. (1999).

- McBride, W. T. (2002).

When you don’t have the author(s)’ name(s), use what you do have.

- When an organization or institution is given in the byline, alphabetize by the organization’s name: first significant word, full name.

- If no person or group claims the piece, alphabetize by its title: first significant word.

- If the piece is officially designated “anonymous,” accept that as a “statement,” and use anonymous in the author place.

How Do I Remember All the Format Pieces?

There are so many little bits and pieces to remember in formatting that trying to memorize them all would probably put most of us in a padded cell. Thus textbooks and publication manuals sell their products, APA web sites get visited, and professors feel warm and knowledgeable because they know more of the little pieces than most of their students.

This is a not a guide for perfectionists who enjoy memorizing things they can easily look up. All of the little nittty-gritties of entering different types of government reports and off-beat web sites are not included; you won’t use them often, and you can easily find them in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2010) or one of the various APA-guidance web sites. What will be covered here are the basic patterns that will help you remember enough that (a) you won’t have to look up everything, and (b) you will have a basis through relationships to understand, locate, and eventually place what you do have to look up.

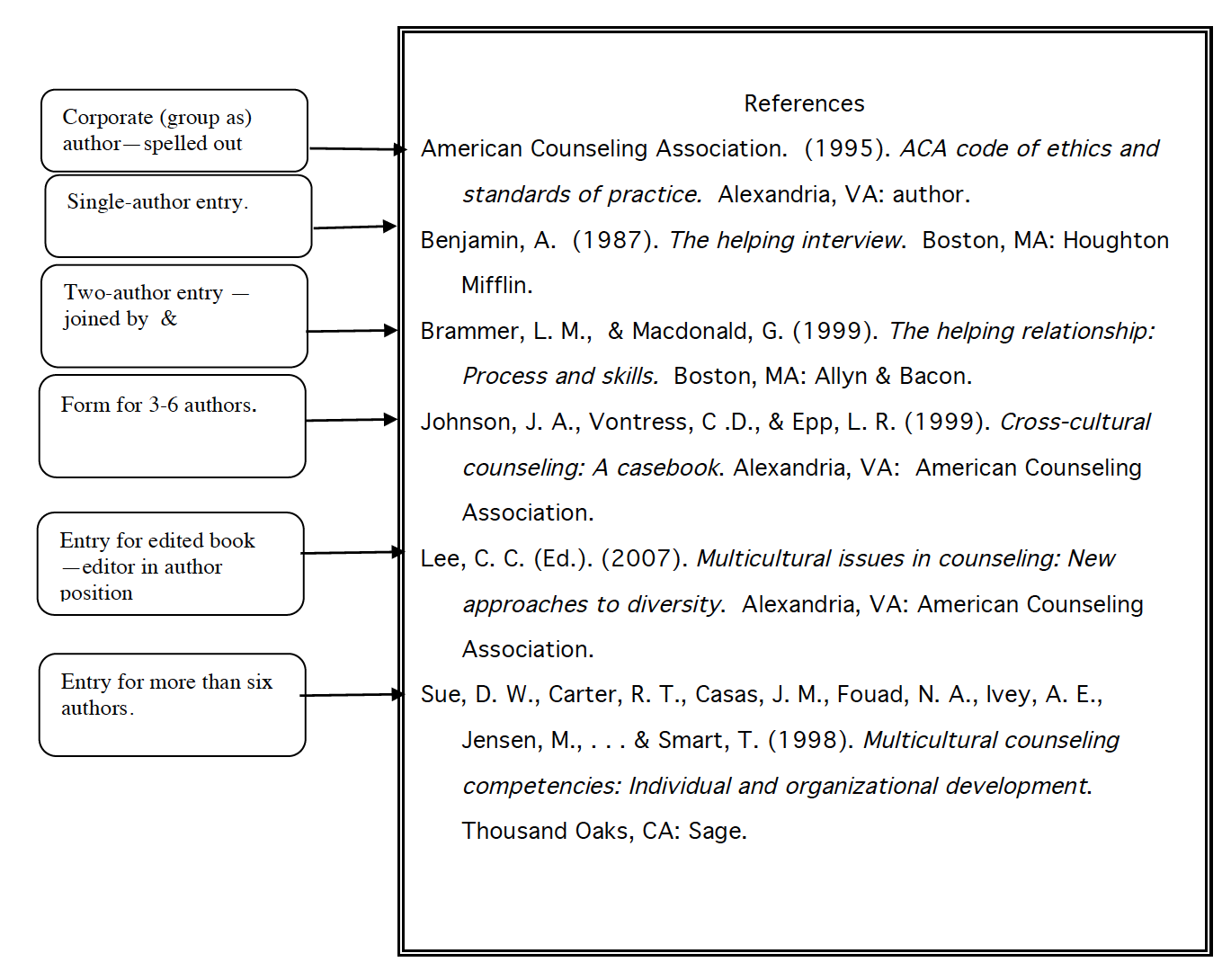

Position 1: Author (SUrnames, Initials, and Lots of Commas and Periods)

- Give the author(s) surname(s), followed by initials.

- If there are more than seven authors, give the first six, followed by ellipsis, followed by the last.

- If a with assistant is included on the title page, include this on the reference list in parenthesis: Brown, M. (with Green, C. Q.).

- If the book is an edited collection and is being cited as the collection, name the editor(s) in the author position followed by ed. or eds.: Davidson, R. M. (Ed.).

- If you are citing a chapter or essay in an edited book, give the author and title of the individual section. Follow this with In and the name(s) of the editor(s) and the title of the book.

- Write out the names of corporate authors rather than using abbreviations.

- Use commas between as well as within all names (including those joined by ampersand); separate name variations (such as Jr. or III) by a comma as well: Wilson, G.W., Jr. (2004). End the author entry, like all major units, with a period.

Position 2: Publication Year in Parenthesis

- Give year of publication—year of production if work is unpublished.

- Give month for things that come out monthly, including meetings (which, we hope, are not more frequent).

- Give day for things that come out daily or weekly.

- If something is not published, give date of preparation and indicate publication status as follows:

- If something has been accepted for publication, use (in press) in the year position. Do not give the year until it comes out.

- If something has not been submitted for publication, write unpublished manuscript at the end of the reference list entry. If a university is involved, add the name of the university (Unpublished manuscript, University of Utah).

- If something has been submitted but not accepted, add Manuscript submitted for publication to the entry. Do not tell which publication or publisher.

- If something is still in draft mode, use Manuscript in preparation. The date should be the date of the draft you read (in the citation also).

- Use a, b, c, etc. after date to indicate more than one work written the same year by the same author (consistent with citations).

- Use n.d. for items for which dates are not given.

- As with the other sections, close with a period.

Position 3: Title - "Simplify, Simplify, Simplify" (Thoreau, 1854/1980)

- Capitalize only the first word of the title; if the title is split by a colon, then capitalize the first word following the colon.

- Do not use quotation marks around article or chapter titles; italicize book and journal titles.

- If an edition or volume number is given, place it immediately after the title, in parenthesis (2nd ed.), (Rev. ed.), (Vol. 3) (Vols. 1-5).

- If you are using a translation of something written in another language, indicate the translator in parenthesis immediately following the title. If you worked from the original foreign language text, use the original title and place a translation of it in brackets next to the title.

- If additional information would be helpful for easy retrieval of the work, include it in brackets:

- [Letter to the editor]

- [Abstract]

- If you are citing an article or chapter in an edited book, include the page numbers of that segment in parenthesis following the book title.

- End the element, as usual, with a period.

Position 4: Publication Information - Or Lack of It (Who, Which, and Where)

For periodical materials, give all information necessary to locate the article.

Journals and other periodicals connect professionals from throughout the world. The good ones are current and reliable.

- Full periodical title, italicized, all significant words in caps.

- Volume number, italicized, followed by comma

- Issue number (if each issue begins with page 1), in parenthesis, not italicized, followed by comma. If pagination is continuous from issue to issue, only the volume number is necessary

- Inclusive page numbers

For books, include place of publication and publisher.

If the publisher is strong and the author/editor reputable, books are solid sources.

- If either the place or the publisher is not given, put n.p. in the place where that information should go (so your professor won’t think you accidentally left it out or forgot to record it).

- Give the city and the two-letter postal abbreviation for the state or the city and name of the country. For books published by universities that include the name of the state, the state should not be repeated: for example, Logan: Utah State University Press.

- Use a colon between place and publisher.

- Give publisher’s name in its simplest form: Omit extra words (Publishers, Co., or Inc.), but retain Books or Press.

- If the book was originally published at an earlier date, then indicate this at the end of the publication information.

- For chapters, essays, or articles within an edited book, give book editor(s) (initials first), title, and inclusive pages of the part being cited (including volume and volume title if necessary). Then give city and state (or country) as above.

For reports, follow the title with any labels or numbers given by the organization of issue that would help a reader in locating the piece, followed by place and source of publication.

Reports provide rich data and important, innovative findings, particularly reports from entities or institutions with strong credibility.

- Give whatever office, institute, or agency produced the report.

- If the specific office is not well known, give the agency as well, larger agency first: David O. McKay School of Education, CITES Research Group.

- If the report is distributed through the Government Printing Office, place this in the publisher’s place: Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- If the report is available through a service such as Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) or National Technical Information Service (NTIS), indicate the service and access number in parenthesis at the end of the entry, with no period following the retrieval number: (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. Ed 454069), (NTIS No. PB 87-146 388/AR).

If a doi number is given, include it at the end of the reference list entry.

An international publishing group has developed an identification system for digital network materials, known as digital object identifier (DOI). Every article is given “a unique identifier and underlying routing system” (APA, 2010), which links readers to information on desired topics, with embedded linking in the reference lists of articles published electronically. When a source with a DOI number is referenced, this identifier must be included at the end of the reference item. It is not followed by a period so that a period will not be misinterpreted as part of the number. The following example is quoted directly from the sixth edition of the APA manual.

Books and Articles

Reports

Presentations

For a conference or symposium presentation, give the title of the conference and the city and state where it was held.

- If the presentation is published in the proceedings, treat it as you would an item in an edited book.

- If it is included in a regularly published proceedings, treat it as you would an article in a periodical.

- If the presentation is unpublished, give the type of presentation (symposium, paper, poster session) “presented at the” and title of the meeting, followed by the location (city and state).

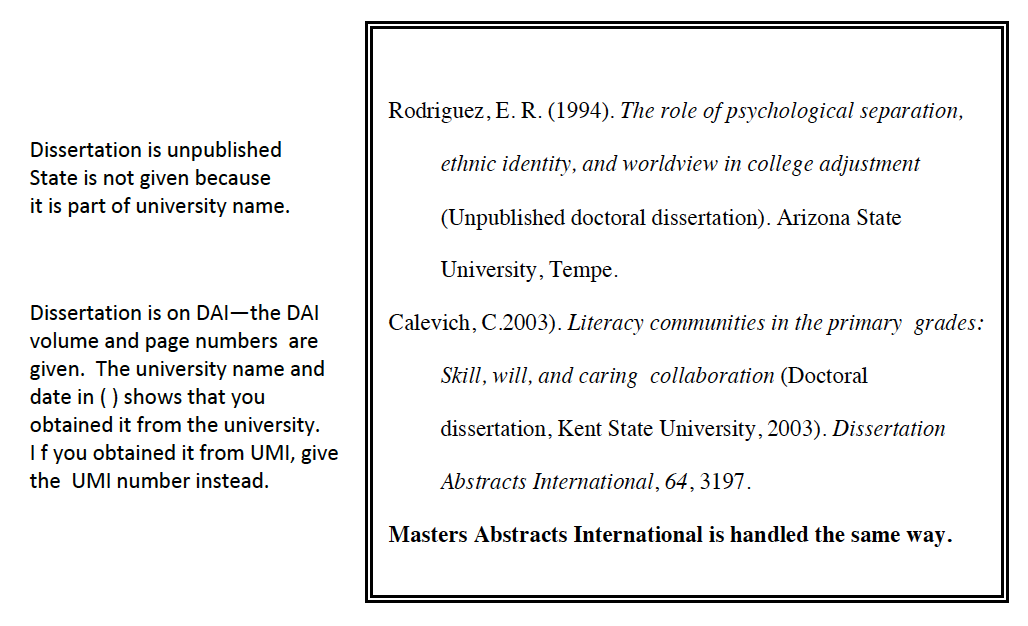

Theses and Dissertations

For theses and dissertations, give author, title, document type, university, and any information that will help the reader in accessing it.

- If the dissertation is abstracted on Dissertation Abstracts International (DAI), follow with the volume and page number of DAI. If you obtained it from UMI, give the UMI number as well.

- If a master’s thesis is abstracted on Masters Abstracts International (MAI), give the MAI volume and page number.

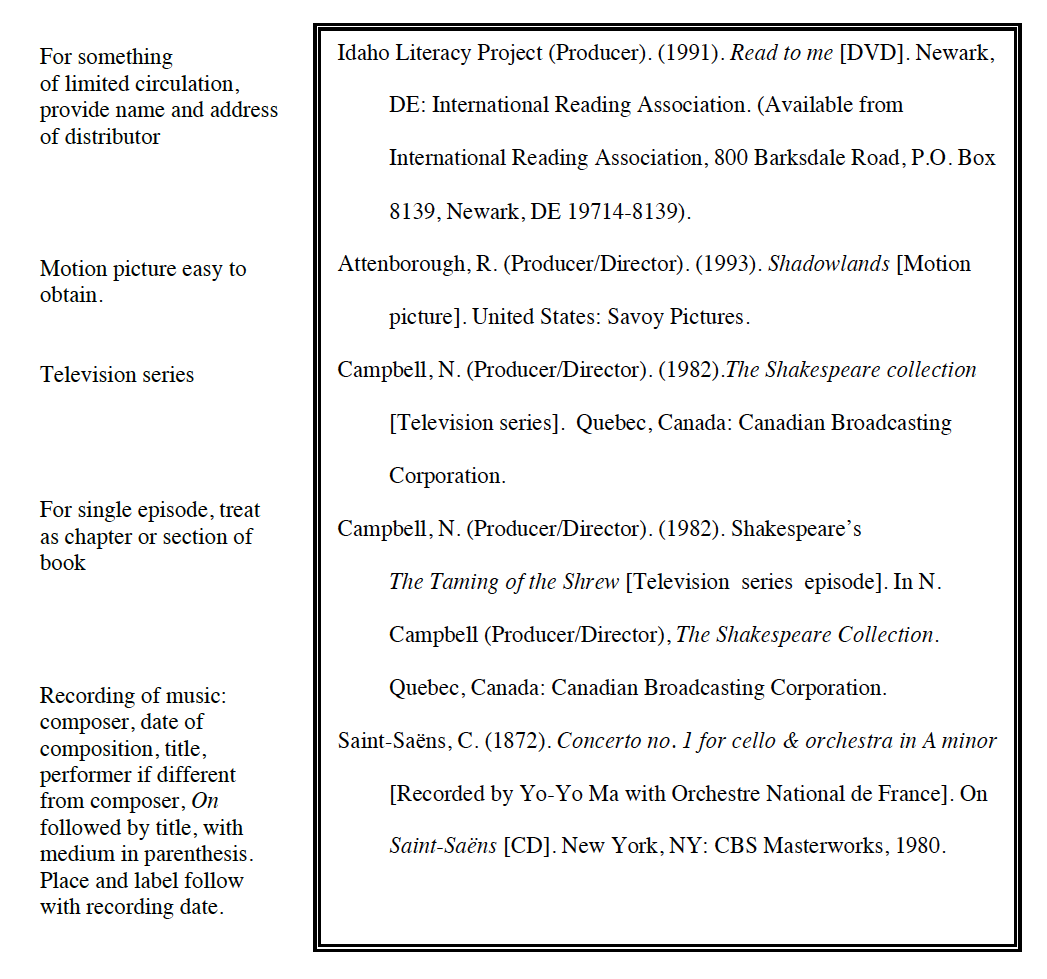

Other Media

For other forms of dissemination give the same kinds of information you would give in any citation, but adapt.

- Indicate principal creators (producer, directer, writer, executive producer) in author position. In most cases, producer, director or both will be given.

- Give date and title, as you would in any citation.

- Indicate the medium (motion picture, television broadcast, television series, DVD etc.) in square brackets following the title.

- End with place and agency/company of dissemination. If the piece is of limited circulation, then give the complete address of the distributor.

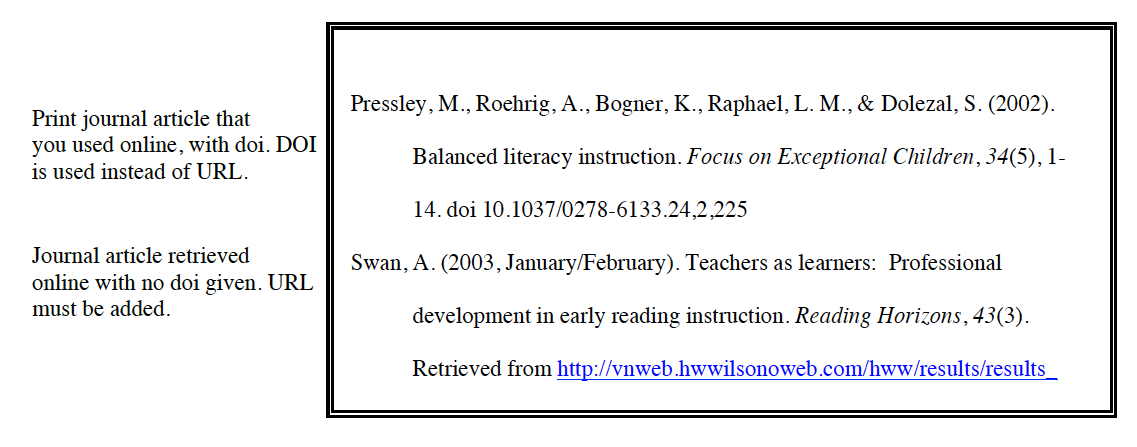

Position 5: Retrieval Information (and Other Electronic Media Considerations)

You no longer need to give retrieval date!

Be sure the readers can easily retrieve your sources and locate any information they might want to verify or use to expand their thinking.

For a journal available in print that you used online, create a regular journal entry but add the URL if a doi is not available.

For a journal or other periodical published only electronically, use the regular article format (including volume, issue, and page numbers if available), followed by the URL.

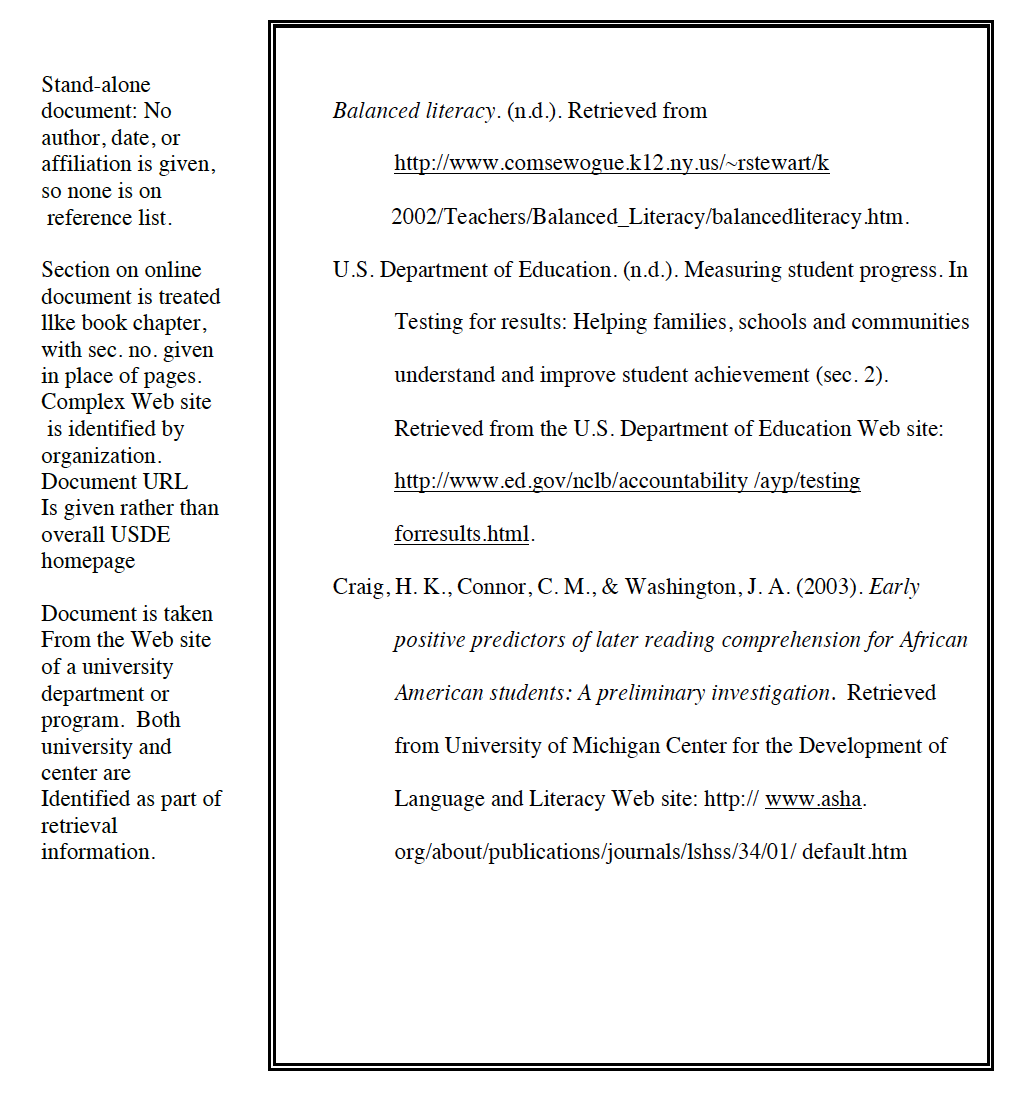

For a non-periodical Internet document, give all information that is available, making it as obvious as you can what information is not available.

- If no date is given, then put n.d. in the date position.

- If page numbers are not given, then substitute the identifier for chapter and section. If neither is available, then use n.p.

- Give the URL that will be the most efficient for a reader who is trying to obtain the document: (1) for a document with multiple pages but not multiple sections, the URL for the home page; (2) for a chapter or section, the URL that links directly to that chapter or section.

- For a Web site that is large or complex, such as a university or a major government or foundation site, include organization and division or department preceding the URL, followed by a colon.

For non-periodical Internet items, the less information available, the more suspicious you need to be. Beware of sites that are not monitored or affiliated.

Yes, there are a lot of technicalities involved with documentation. You have to remember when to cite, how to set up a citation, how to organize and format the reference list, and—worse still—how to get the format right for all those little bits and pieces that readers need to know in order to locate your references quickly and efficiently—if indeed they want to locate the references at all. How can you possibly remember all of this?

Most of us can’t—or won’t. As with so many things in and out of academia, we remember what we use most and learn where to look up the rest. After you have done enough citations and reference list entries, you’ll remember the items that your particular project forces you to use often; you’ll be able to do them smoothly as part of the spontaneous drafting process. The more obscure things you can look up.

The sixth edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2010) includes many more reference categories than the fifth edition. As the number of possible information sources has increased, ways that sources can be categorized and retrieved have increased as well. Since people use game reviews and blog posts to retrieve information for publications, and as a variety of archival systems have developed, the APA has chosen ways to have these matters documented consistently. You need to have the Publication Manual so that you can look up the formats for the less common types of sources when you need them. In addition to the areas treated in this book, you will find formats for the following:

- Reviews and peer commentary (including reviews of videos and video games)

- Audiovisual media (including online maps and podcasts)

- Data sets, software, measurement instruments, and apparatus

- Unpublished and informally published works

- Archival documents and collections (including letters, personal collections, and photographs)

- Internet message boards, electronic mailing lists, and other online communities (including newsgroups, discussion groups, electronic mailing list posts and blog posts)

You can include just as much variety and sophistication in your sources as you want. Just remember—you have to document the stuff.