Learning Outcomes

In this chapter, you'll learn the steps to creating a literature review including

Note: Because this chapter involves the steps for writing your Literature Review, the discussion questions in each section will be more involved than in other chapters, so give yourself extra time. But never fear! They will all lead to writing a better paper.

11.1 Take Notes Like a Boss

Good notes will make your life much easier! Photo by Elijah Hail on Unsplash

Good notes will make your life much easier! Photo by Elijah Hail on UnsplashRemember back in Chapter 3: Writing Processes where we introduced you to the steps of the writing process? And do you remember that the first step is to Plan? I hope so. Because for a big paper like a Literature Review, the more you prepare and plan, the better your paper will turn out. Trust me; you don't want to jump into this one the night before it's due. Or even the week before it's due. The key to a good Literature Review is finding the patterns and connections between sources and synthesizing those sources rather than just talking about them individually. Therefore, before you begin writing or even planning what to write, you need be sure you've done your homework and have good notes to work with. For the purposes of this section, I'm going to assume that you've already done the steps in Chapter 8: Finding and Evaluating Sources: you've created a research question, gathered many relevant and reliable sources, annotated your sources, taken good notes, and hopefully even written an Annotated Bibliography.

Recall from Chapter 1 that any publication is written as part of an ongoing conversation. So it helps to view all the sources you've found as contributions to the larger conversation in your field. Your job is to figure out the most important threads of that conversation. For this reason, a good Literature Reviewer synthesizes the sources—compares them and shows them in a larger context—rather than just talking about them individually. Like Marty McFly, your readers need the big picture.

“A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.”

—The Writing Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

I know in Chapter 10 we talked mostly about looking at what's been done before. But the truth is, even though the past is your focus in a literature review, like in the movie Back to the Future, you'll also want to keep in mind the present and future.

Map out the past, present, and future of research. Feel free to use a time-traveling Delorean. Photo by Jason Leung on Unsplash

Map out the past, present, and future of research. Feel free to use a time-traveling Delorean. Photo by Jason Leung on UnsplashImagine you're getting into your time-traveling Delorean so you can figure out

- the past—how far research has come

- the present—where researchers are currently focusing their research, and

- the future—where gaps in knowledge appear that can be filled by tomorrow's researchers.

What is Synthesis?

Throughout the rest of this section you'll be going through a tutorial created by superstar research librarian Emily Swensen Darowski and illustrious associate professors Nikole D. Patson and Elizabeth Helder Babcock to take you through the process of synthesizing sources. Have your notes from your sources ready and follow the instructions after each video.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) Step 1: Color-Code Your Notes

Color-Code Your Notes. Photo by Sara Torda on Unsplash

Color-Code Your Notes. Photo by Sara Torda on UnsplashThis is where your notes will come in handy. If you've already color-coded your summaries from your sources, then you're one step ahead. If not, don't worry. Just watch this video and follow the steps. Remember, you can use paper cards or electronic note-taking software like Trello.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/Zcp0bov2svo

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/Zcp0bov2svoStep 2: Look for Patterns

Can you see patterns? Photo by James McDonald on Unsplash

Can you see patterns? Photo by James McDonald on UnsplashNow you're going to take your note-taking to the next level as opposed to just writing general summaries like you did for an Annotated Bibliography. This time as you read through your notes and sources, you'll be looking for patterns and themes that emerge.

If you're writing a stand-alone literature review, then you don't need to look for all the items listed in the video. (A stand-alone literature review means the kind that's published on its own and is not the introduction to a bigger empirical research project report or IMRAD format paper. Most students will be writing a stand-alone literature review). In that case, you just need to look for things that help you see what's happening in the field, what researchers are doing. So you can ignore the items in the video such as "Methodology that you might 'borrow' for your proposed materials or procedures" because you won't be conducting any experiments or primary research in this class. Your teacher might eventually ask you to propose research in a grant proposal, but that's the most you'll have time for. So for now, just focus on the items relevant to a literature review as you organize your notes.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/7bDVx3iicbE

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/7bDVx3iicbEI tell my students to ask four questions as they look through their sources and notes:

- What do researchers agree and disagree about?

- How are researchers narrowing or changing their focus to create new information?

- What are each study’s limitations and strengths?

- What’s the next step in research—what should be studied in the future? (The research gap)

Revisit your sources from your Annotated Bibliography. Look through them again looking for these patterns:

- Similarities/Differences

- Relationships

- Areas of inquiry

- Areas of controversy

- Gaps

Another way to think of these groups is to think heat: Where are the hottest areas of research? What are the most heated debates? Which studies are the hottest—most cited? Which are only lukewarm because they have major limitations/weaknesses? Where does the research go cold (where are there gaps that need to be filled)?

Step 3: Organize and Group

Group your notes into themes or umbrellas. Photo by Alex Blajan on Unsplash

Group your notes into themes or umbrellas. Photo by Alex Blajan on UnsplashNow you can group your notes into themes or umbrellas based on the four questions you've been asking yourself. Or if you notice similarities or connections between sources, feel free to make an umbrella based on that. This process doesn't have to be perfect, so don't get caught up in making things match perfectly. The point is that you're starting to organize your notes based on your own agenda.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA)

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA)

https://youtu.be/TJNoymVkqlI Here's what you can consider about each of the four questions from above:

1. What do researchers agree and disagree about?

Many students are tempted to simply report on what's been established and agreed upon in their field, but the problem with this is that if everyone in your field agrees about something, then it becomes common knowledge and no longer counts as a gap in knowledge. So if you only report on what is commonly agreed upon, you're actually writing a descriptive report rather than a synthesized literature review. Students in fields like Public Health where reports are common need to pay extra attention to avoiding this tendency. Reports are great when explaining something like the difference between symptoms of the common cold versus the coronavirus—you want to focus on the most agreed-upon information in that case. But a literature review has a different purpose: to unearth the gaps and disagreements where the most fruitful areas for future research are.

If most researchers seem to agree, all is not lost; that information can become background information for your literature review. So take note of common knowledge in your field, but focus your search on areas of disagreement.

2. How are researchers narrowing or changing their focus to create new information?

Remember as well that researchers are constantly trying to create new information. They do this in two ways:

- by narrowing or shifting their focus or

- by taking something that's been done before and doing it in a new way as a type of re-vision.

It's your job to point out how researchers in the field are currently creating new information and where you think the field is going next (aka the gaps in research). If you notice, for instance, that researchers have started to look at specific geographic areas but they haven't yet looked at different age groups, then this could be an area for further research. It's valuable to show a trajectory of how variables are being narrowed because that helps us know where things are bound to go in the future as well.

3. What are each study's limitations and strengths?

When I have a student who's struggling with synthesis, I often tell them to go through each source and simply write out the strengths and weaknesses. It's a great way to start because it gets their analysis juices flowing. Perhaps a limitation is in methodology—is the study reporting on a small number of participants? That usually allows for richer data (a strength) but at the cost of being able to generalize to a bigger population (a weakness). Is the study only quantitative in nature? That allows for easily measurable results about larger populations (a strength), but perhaps they are missing the richer data interviews or qualitative surveys could produce (a weakness). Does someone's interpretation of results seem to miss what another research group published? Ta da! You've found a gap that can be filled with future research.

One more way to take note of limitations and strengths is to pay attention to which sources are cited the most and have had the most influence in your field. You can generally assume that the more a source is cited, the "stronger" the research.

4. What’s the next step—what should be studied in the future? (The research gap)

All of this is leading to the ultimate goal of a literature review, which is to show where researchers should go next. As you analyze your sources and find places where further research would add knowledge to your field, take note. You can organize these "gaps" into themes or umbrellas as well and include them in your literature review. In terms of hoverboards, the point of a literature review is to figure out what's been done—and more importantly, what hasn't—so you can pinpoint where the best place is to take the next step and remain on that cutting edge.

Make a Map

Make a map of your sources. Photo by oxana v on Unsplash

Make a map of your sources. Photo by oxana v on UnsplashAs you compare sources and group your notes, you'll be able to figure out the main paths that the conversation is taking. This is why Literature Reviews are generally organized around themes rather than simply a list of information about each source separately. In fact, most Literature Reviews are organized in one of these four structures:

- Similar concepts or themes

- Similar methods

- Chronological development

- Controversies

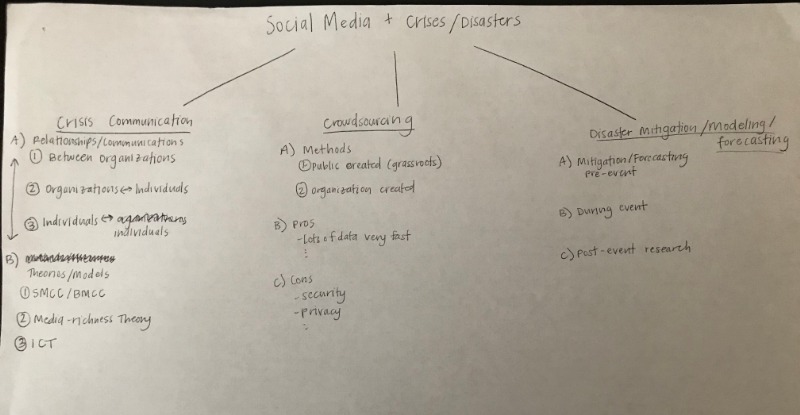

My students often find it helpful to literally make a map of their sources to show where themes are emerging. This is similar to the creative mindmapping we talked about in the brainstorming section earlier. As with brainstorming, it often helps to physically draw the connections because it encourages your creativity and your ability to see relationships. Here's an example of my awesome geography student Carly's paper on the uses of Social Media during Crises and Disasters. Making a map of her topic and what she found in her sources allowed her to visually see where the areas of inquiry are in her field. This map could easily be used to create themes for her notes or even to structure her outline for her literature review.

A student's mindmap for her paper showing areas of inquiry around the topic of social media use during disasters. (Used with permission)

A student's mindmap for her paper showing areas of inquiry around the topic of social media use during disasters. (Used with permission)Step 4: Assess Groupings

It's time to look through the way you've grouped your notes and see where your sources are landing. Make sure you have multiple sources under each theme/umbrella so you'll be able to synthesize once you get to the drafting stage. If you don't have enough sources under a theme/umbrella, this is a good time to either look for more sources or decide that this particular theme is not important enough to include. Once you feel like you have enough sources under each group, you can probably see how your paper's outline will emerge from this organization. (We'll talk all about outlines in the next section.)

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/E0AsfD4ih2I

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/E0AsfD4ih2IStep 5: Write a Paragraph

Now you can try writing a paragraph that synthesizes the sources under one of your groups of notes. If you can include synthesized paragraphs like this throughout your paper, your literature review will be much more sophisticated than a simple annotated bibliography or descriptive report—you will show that you understand the areas of inquiry in your field and how researchers are approaching your topic.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/1E_ZlVsrBNQ

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/1E_ZlVsrBNQStep 6: Check Out an Example

As a final step, watch this video to review the steps and check out an example.

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/zjzm99oNf5E

Watch on YouTubeBy Emily Swensen Darowski, Nikole D. Patson, and Elizabeth Helder Babcock. (CC-BY-NC-SA) https://youtu.be/zjzm99oNf5ENow that you've started organizing your notes into themes, patterns, and idea umbrellas, you're ready to start thinking about the structure of your paper. So we'll take a break from working with notes and think through the structure of a literature review.

11.2 Structure Your Paper

A Literature Review follows a general structure. As you start organizing your ideas and formulating what you want to say, think about how and where your ideas will fall into this basic structure:

- Title Page

- Abstract

- Introduction (with Thesis Statement)

- Body Paragraphs (with Headings)

- Discussion/Conclusion

- References

In addition, your teacher might ask you to include other elements like a Table of Contents, List of Tables and Figures, or an Appendix.

I'm going to cover each of the main elements of Literature Review structure, but instead of talking about them in the order they go in your paper, I'm going to talk about them in the order you should tackle them. Trust me, it'll make your life easier.

Thesis Statement

Now that you've grouped your notes and seen patterns emerge, you're ready to create the crux of your literature review: the thesis statement. But don't be fooled into thinking that you're writing a typical research paper with an argumentative thesis statement where you take a position on an issue. In contrast, your position in a literature review is simply what you believe to be the state of the field on an issue. Some people call it an expository thesis statement because it exposes or announces your topic rather than taking a position or arguing your opinion. So any claim you make will be determined by the sources that you've been organizing and grouping and the trends or patterns you found. One way to think of a literature review thesis statement is in two parts:

Thesis = Main Areas of Inquiry + Future Research Directions

Areas of Inquiry

In other words, you will describe what you think the main areas of inquiry are concerning your topic. This is the new knowledge you're personally bringing to the table and that justifies writing a literature review—now that you've read and analyzed your sources, you can tell us your findings. And your findings consist of the fact that researchers in your field are congregating in certain arenas—also known as areas of inquiry. Your job is to point out where those areas are.

Go back to your notes from the Synthesis activities in the last section and also do some mind mapping until you have decided on 3-5 main areas of inquiry you want to talk about in your paper. If you're organizing your Literature Review chronologically or by methodology instead of by theme/area of inquiry, then you can divide your ideas in to 3-5 sections based on those perspectives. Either way, you can even write out the headings you would use for each section.

Future Research Directions

And because there are still limitations or gaps in knowledge, you're also in a position to explain where you think future research should go. These are your main findings or "results" in a Literature Review. So your thesis statement—or main point—is a combination of your main sections and your findings. You'll eventually put this statement at the end of your Introduction.

Length

Another difference between a typical research paper and a literature review is that in the former, a thesis statement is short—one or two sentences—and makes a claim; in contrast, a literature review thesis statement can be as long as a paragraph. In fact, the thesis statement can serve two purposes: it can explain your main point and it can indicate the organization of your paper. (Be sure to list everything in the same order you'll talk about them in your paper.)

For example, my student Justin's thesis statement is actually a paragraph long and sets up the organization of his paper. (This came at the end of his Introduction.)

In this paper, I will give an overview regarding the history of Africa’s relationships with their traditional investors and then compare that to China’s relationship with Africa now. I will then cover the three main ways that China is involved with Africa which are FDI, trade, and aid and discuss what researchers have found both China and Africa have to offer in all of these interactions. Then I will synthesize how current researchers agree and disagree regarding both the positive and negative effects of China’s interaction on Africa from a macroeconomic and microeconomic level. I will then end this review by offering what researchers say is the future of Africa based on their relationship with China.

As you can see, this is very different than a typical thesis statement. It's long and doesn't take a stand on an issue. But it still serves the purpose of delineating the main points of his paper—areas of inquiry and research gaps—and setting a direction for where he'll go.

Write a Thesis Statement

Now it's your turn to try creating a preliminary thesis statement to go at the end of your Introduction. List the 3-5 main Areas of Inquiry that you've found based on your topic. Then list the main gaps you've found in the research and where you think further research should go. Now write these things out into a few sentences that could go at the end of your Introduction. You might have to revise this later, but it will be a good start.

Outlining

Outlines are like topiaries. Photo by Dean Moriarty from Pixabay.

Outlines are like topiaries. Photo by Dean Moriarty from Pixabay.Once you have a basic thesis statement—or even as you're trying to create one—you can start organizing your ideas into an outline. Your notes should already be grouped under umbrellas, so it shouldn't be too hard now to make a general outline of the rest of your paper. There are two types of outlining you can choose for setting up your paper: the formal outline (aka the structured outline) or the organic outline (aka the unstructured outline). Dr. Matt Baker (2019), a BYU Linguistics professor, has studied the way students create outlines and likes to compare the two types of outlining to making a topiary—you know, those shaped trees or bushes that often look like animals (they're especially prevalent at Disney resorts).

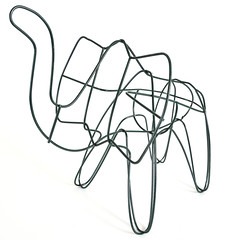

Organization-Only Outlines are like the topiary wire frames that a bush will grow into. Photo by Mike Atkinson on Flickr.

Organization-Only Outlines are like the topiary wire frames that a bush will grow into. Photo by Mike Atkinson on Flickr.Baker calls the formal/structured type of outline an Organization-Only Outline and says this is similar to the formal way gardeners create topiary bushes. The formal way is to create a metal wire frame first and then grow the bush into the frame until it's shaped beautifully. This is like the types of formal outlines you're probably most familiar with that use Roman numerals:

- Introduction

- Main Point #1

- Sub-topic A

- Sub-sub-topic i

- Sub-sub-topic ii

- Sub-topic B

- Main Point #2

- Sub-topic A

- Sub-topic B, etc.

If you already have a good sense of where you're going with your literature review, then this can be a great way to start filling in the details. You can make your major umbrellas/areas of inquiry your main sections—the first level of Roman numerals (I, II, III, etc.)—and start adding subsections underneath. Your notes should help you a lot with this.

The second type of outlining is more organic. Baker calls this type a Content-Exploration Outline. This involves many of the idea-generating activities we've done like brainstorming, mind mapping, and grouping as well as just plain writing sentences and paragraphs. This is like the type of topiary where a gardener sees a full-grown bush and starts trimming it from the outside-in to create a shape. You can group ideas and work on one area and then another as your paper takes shape. You can write the sentences and paragraphs that feel the most fruitful and then work on another preferred section next.

Organic Content-Exploration Outlines take shape as you develop your ideas and even start writing. (Public Domain)

Organic Content-Exploration Outlines take shape as you develop your ideas and even start writing. (Public Domain)You can even write a whole rough draft and then create an outline in reverse to see the bigger picture of how you organized your ideas and revise from there. Many students don't recognize these activities as types of outlining, but they are because they help organize your ideas, which is the whole point of a formal outline as well.

“Over the course of my 17-year writing career, I began to give up on outlining — that is, before I write. I’ve come to prefer a more organic approach to creation, first laying out my raw material on the page, then searching for possible patterns that might emerge.”

—Writer Aaron Hamburger (2013) in NY Times article “Outlining in Reverse”

Of course, you can also have a combination of both types of outlines, which is what most students do. As you may have noticed, the activities we've done earlier in this chapter have had the purpose of helping you to organize your ideas into the shape of a paper. You might be tempted to skip this stage of the writing process, but research shows that if you take the time to organize your ideas, your writing will be

- more efficient (Kellogg, 1988),

- higher quality (de Smet, Broekkamp, Brand-Gruwel, & Kirschner, 2011; Kellogg, 1987),

- and more satisfying in the end (Torrance, Thomas, & Robinson, 2000).

Those are pretty good benefits!

Here is an example of a Literature Review outline for one of my student's papers. Pay attention to the content but more importantly, notice the structure of her paper.

Home-Based Therapy for Children with Autism

-

- Introduction

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Definition

- Occurance

- Autistic children

- Current research/study methods

- Current treatments

- In-home or in-school?

- How the environment affects autistic children

- Sensory enrichment therapy

- Definition

- Useful for autistic children?

- How the studies were administered

- Positive/negative results

- Limitations

- Parent-involvement in therapy

- Home-Based Therapy

- PLAY Project Home Consultation program

- Purpose

- Results

- Quantitative measurement

- Caregivers biased?

- Qualitative measurement

- Specific autism symptoms tests used

- Results of home-based therapies

- Effect of home-based therapy on family

- Positive

- Easier to do things in familiar environments

- Negative

- Strain on parental relationships

- Strain on sibling relationships

- Future Research

- Long-term goals

- Have a long-term follow-up to current home-based therapies

- Positive/negative results of following-up long-term (use specific study)

- More test subjects

- Family-centered approach only done on 1 family

- Not enough subjects = can’t be statistically significant

- Conclusion

- Children with autism

- Effect of the environment

- Effect of the home

- Home-Based therapy

- Effect on family

- How effective it is for the child

- Maybe quickly reiterate the future research needed?

**I honestly could use any suggestions on how to organize this better. I've spent hours trying to organize my sources/info better but could use any thoughts y'all have on how to make it better!

My favorite part about this outline is the comment at the end that this student invites any suggestions for improvement. That shows exactly the right attitude when writing—be open to feedback. The beauty of creating some type of outline now is that you can get feedback on your ideas and organization before you go through the work of writing out all your beautiful sentences and paragraphs.

Create an Outline

Now start creating a rough outline of your paper. You can do this by making a detailed formal outline with Roman numerals or you can do the more organic approach and start writing out ideas, sentences, and paragraphs. But if you choose the second option, you also need to show that you're starting to organize those ideas into a structure. You can read Chapter 12 if you want more details about the specific parts of a literature review. Ask for feedback on your outline before you do more writing work.

Now that you have a sense of the structure for your own Literature Review, you're ready to start drafting your paper. Luckily, Chapter 12 is all about drafting.

References

Baker, M. J. (2019). Pain or gain? How business communication students perceive the outlining process. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 82(3), 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490619831277

de Smet, M. J. R., Broekkamp, H., Brand-Gruwel, S., Kirschner, P. A. (2011). Effects of electronic outlining on students’ argumentative writing performance. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27, 557-574. https://open.byu.edu/-pPk

Kellogg, R. T. (1987). Writing performance: Effects of cognitive strategies. Written Communication, 4, 269-298. https://open.byu.edu/-MCb

Kellogg, R. T. (1988). Attentional overload and writing performance: Effects of rough draft and outline strategies. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 14, 355-365. https://open.byu.edu/-ejdu

Torrance, M., Thomas, G. V., Robinson, E. J. (2000). Individual differences in undergraduate essay-writing strategies: A longitudinal study. Higher Education, 39, 181-200. https://open.byu.edu/-PJo