Many of us enjoy a good mystery. Someone has done something dastardly (or at least interesting), and the detectives must figure out who did it and how. Why, when, and where usually emerge as well. But the basic beginning is the perpetrator and the deed.

Putting information together in a sentence works the same way. We begin by asking who and how, then select words to express it and punctuation to enhance it. We assemble the rest of the relevant information and place it in clear logical positions to build and develop our ideas.

Sentence structure is based on communicating meaning, and punctuation is based on sentence structure. It’s that simple. Grammar is a little more rule bound, but understanding structure is important to handling grammar as well.

This chapter will help you in exploring the mystery of sentencing. Since the style, stance and conventions of academic writing may not be those you are most familiar with, a brief discussion of appropriate style will lead off the chapter. Some processes and hints for putting together the sentence (aligning the who, what and how) will follow. Since punctuation is based on the alignment of sentence elements, common uses and misuses of commas, semicolons, colons, and dashes will be discussed in the context of the sentence (other punctuation challenges will be treated in following chapters). Once the basics are in order, it’s time to trim off the excesses that sometimes make social science writing difficult for a reader to process. So this chapter ends with a quick guide for getting rid of wordiness and making your sentences efficient and clear.

Representing Yourself

Many of us find great consolation in Henry David Thoreau’s (1854/1980) oft-quoted statement that if a man is out of step with his fellows, perhaps “it is because he hears a different drummer” (p. 216). There are endeavors in which listening to a different drummer is just fine (and a lot of fun), but writing an academic paper, thesis, dissertation, or article isn’t one of them. Certain expectations have to be met—among them, basic academic style.

Don't Present a Formal Case in Your Casual Clothes

Style in writing is like style in clothing. It will vary according to situation, purpose, and audience. To violate what is appropriate may feel exhilarating, but it is risky. You can be comfortable, casual, and “yourself” when you’re jogging or picnicking, but when you’re presenting yourself as a scholar, you’re expected to adopt a scholar’s style.

Present Yourself as a Competent Professional

Yes, this book is written in a blue denim tone and style. It was intended for an audience of students (graduate and undergraduate) who have been feeling intimidated by the thee-piece business suit style of the regular publication manual. Its purpose is to downshift style to make conventions easier to understand. If the author wore sophisticated verbal attire, you’d close it immediately.

But your academic paper, thesis, dissertation, or article is intended for academic professionals, whose ranks you are attempting to join. You need to come across as a professional addressing professionals. You don’t have to use the verbal equivalent of a three-piece business suit or 3-inch high heels, but you do need at least a tucked in shirt and a tie (if you’re male) or an appropriate feminine equivalent (if you’re not). Be conservative—most of your committee is probably over 30.

- Use a tone that is objective, not personal; avoid words that reflect subjective feelings and emotions. Words like feel and think are not appropriate, even when discussing what others have written (Szuchman, 2002).

- Avoid slang or other popular conversational usage—even words like awesome or terrific mark you as being too informal or frivolous.

- Avoid contractions or shortened word forms. Use only those abbreviations that are accepted in the professional literature of the field (used in top-tier professional journals).

- Use conservative grammar. For example, avoid leaving out relative pronouns such as “the hypothesis that the researcher hoped to prove.” You can get by with ignoring the who/whom distinction in a personal essay, but don’t try it on the dissertation.

- Use professional terminology when needed and appropriate, but don’t use “big words” just to be using them. Avoid buzz words, particularly those with very imprecise meanings.

- Use clear, direct sentences. Vary sentence length. As with paragraphs, too many short sentences in sequence can be choppy, but too many long ones in sequence can be asphyxiating. Sentences do not have to be messy in order to convey complex meaning.

Making Your Case and Nailing It with a Sentence

Conversational sentences are sloppily put together. We speak as we compose (or someone will interrupt us and attempt to finish the sentence—and probably get it wrong). We don’t have time to clarify ideas and put important elements in strategic positions. And the listener (who is focusing more on his or her own response than on what we are saying) doesn’t have the time or the concentration to be sensitive to our elements and positions anyway.

But writing is different. We do have time to put things together carefully and purposefully, and the reader can (or should) be sensitive to the way things are expressed. Since we do not have the instant feedback or the face-to-face clarification opportunities that we have in conversation, deliberate writing and careful reading become very important, particularly when we are dealing with important or complex information.

In order to construct a clear and purposeful English sentence, you need to know what you’re constructing. Both sentence economy and punctuation are based on sentence structure. Once the structure is in place, you are ready to cut out excess words that interfere with your meaning and then punctuate accurately. This section will deal with the structuring part.

Look First at What the Sentence Should Do

Think of the sentence as a verbal investigation. As you structure it, you need to decide what is important and place important materials in strategic locations. You need to present your thinking to the jury of your readers in as clear and efficient a manner as possible.

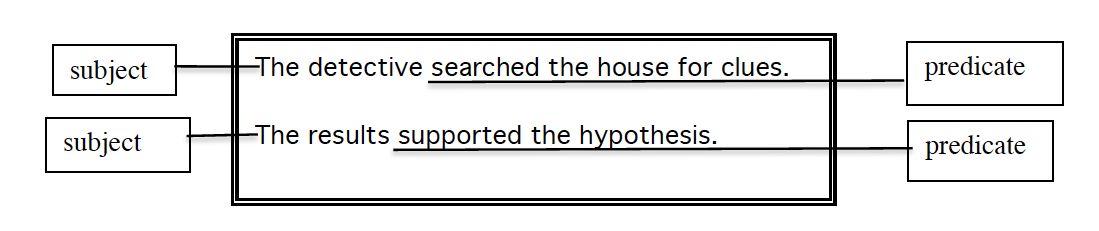

The core of a sentence, like the core of the case, consists of a perpetrator and an occurrence. You probably learned to call these things a subject and a predicate.

- The subject is what the sentence is about.

- The predicate makes a complete statement about the subject.

Whether you’re dealing with criminal investigations or academic ones, the basic elements are the same.

Learn what the core elements are so you can line them up accurately.

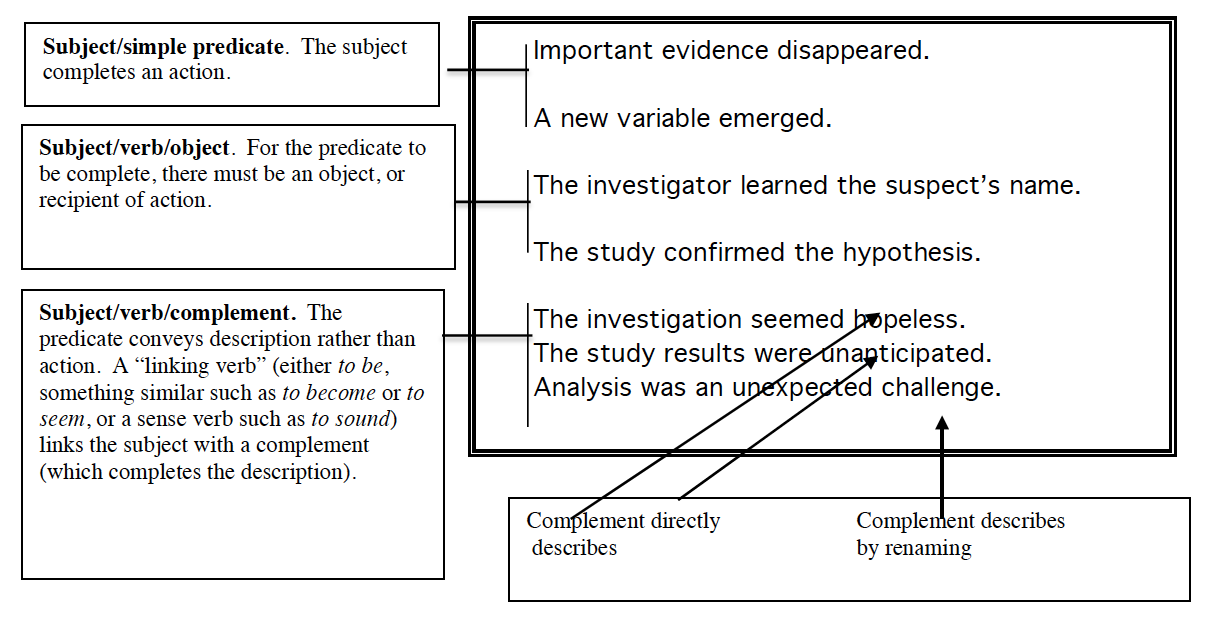

In order to structure and punctuate correctly, you need to recognize three kinds of subject/predicate structures.

For Clarity, Efficiency, and Reader Accessibility, Put the Most Important Sentence Information in the Core

The reader shouldn’t have to search through muck to find meaning.

Even When Cores are Long or Complex, the Strategy Remains the Same

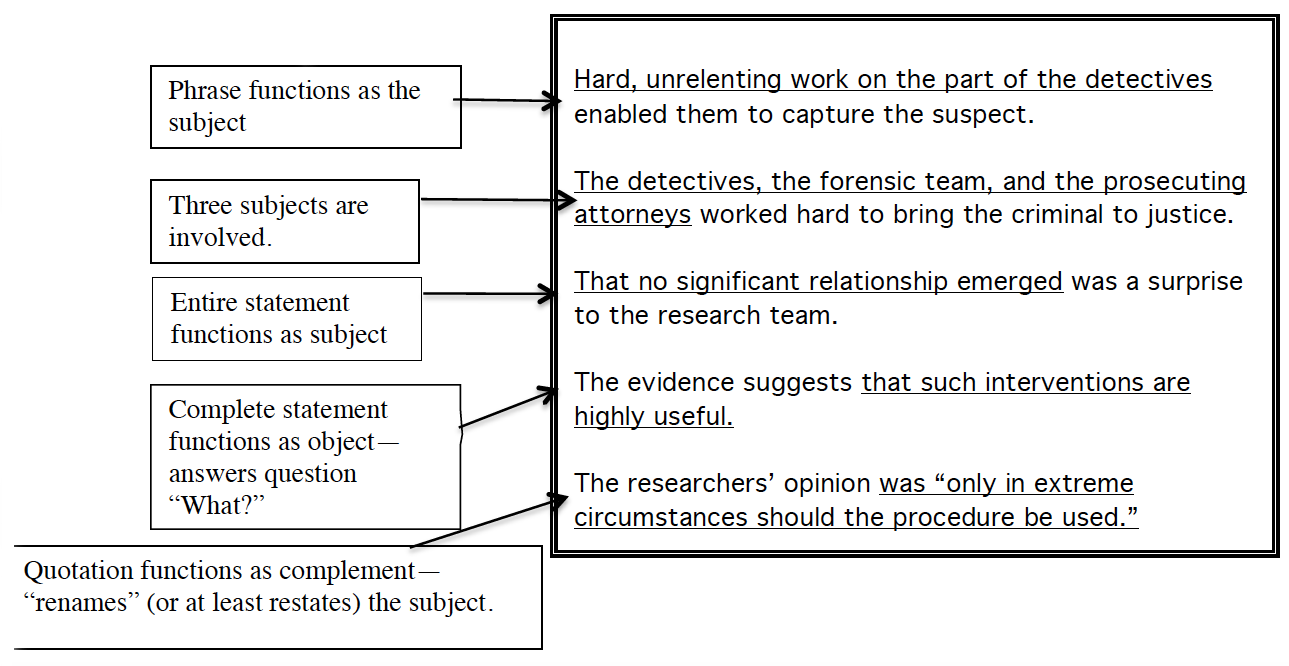

Sometimes a basic element (subject, verb, object, complement) will consist of a phrase (two or more words) or a clause (an entire statement).

Sometimes one of the elements will consist of multiples (more than one subject, more than one action etc.).

But the elements still have the same function.

Even though the basic elements in these sentences are more complex, they are still in the sentence core. The sentences are thus direct and efficient.

Be Sure that the Core Elements Actually Have a Logical Subject-Predicate Relationship

When a writer is tired or in hurry, it’s easy to express general relationships in the first wording that comes to mind, even though the choice may not be entirely accurate. Avoid subject-predicate mismatches such as the following:

|

Illogcal

|

Reason

|

More logical relationship

|

|

The study said [or concluded explained, clarified etc.]

|

A study is not alive; it doesn’t talk, write, or draw conclusions from its evidence

(see Szuchman, 2002).

|

After conducting the study, the researchers said [proposed, explained, suggested recommended etc.]

|

|

Study results conclude

|

Results consist of data that can demonstrate, but concluding and applying are human actions.

|

The results of the study show, confirm, support or fail to support, demonstrate, illustrate, or provide evidence.

|

|

The article (or book) talks about

|

Articles and books don’t talk. Really strict constructionists also discourage “the article says” (see Szuchman, 2002).

|

The article describes, explains, recounts. (An explanation or a description is published in a book or article.)

|

Punctuating to Promote Clarity

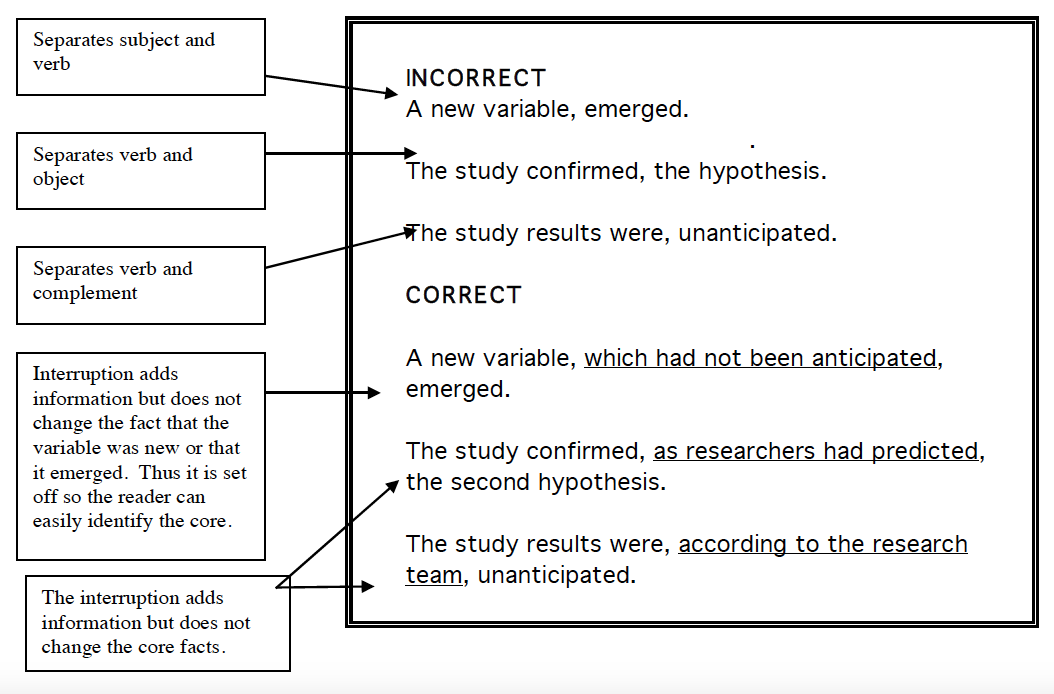

There are two main points that you need to remember in order to use punctuation correctly. All the individual punctuation rules go back to these guidelines:

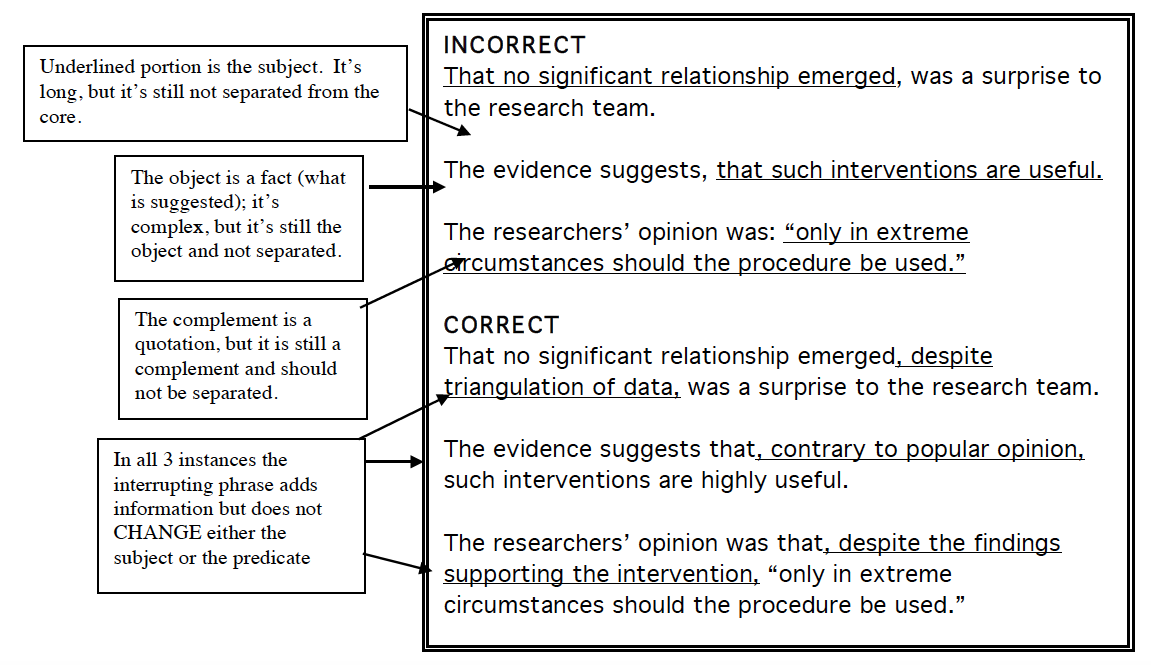

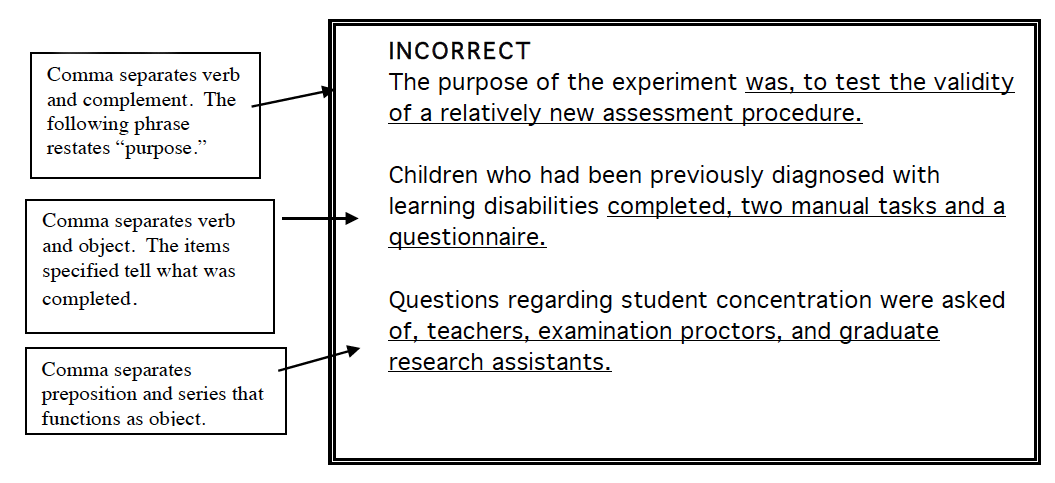

- Do not use punctuation that would interrupt the sentence core: comma, colon, or anything else.

- Use a pair of punctuation marks (commas or dashes) to set off elements that interrupt the core. By doing so you make it easier for the reader to discern and relate the core elements.

The same principles are true no matter how long or complex the sentence elements get.

Applying Specific Punctuation Rules

Keeping in mind that the purpose of punctuation is to clarify and emphasize the sentence core, you can remember the various punctuation marks and their uses by extending the analogy of signs and signals from Step 3.

Just as traffic signals control the flow of traffic, punctuation signals control the flow of ideas.

This is just a memory device—but memory devices are sometimes easier to apply than intellectual rules. Don’t try to take everything too literally—just use the analogy as a system for recall and basic application.

The Comma is a Blinking Yellow Light

As a blinking yellow light, a comma indicates a minor intersection of ideas. It tells you that you don’t have to come to a complete mental stop; you just have to exercise caution to void running things together.

You might have had a high school textbook with 30 comma rules. No wonder you decided to just put a comma where you felt like breathing. There are two common fallacies you need to get rid of.

- You don’t need to learn 30 comma rules. If you can remember four uses and two misuses, most of the others are really only applications of them.

- The only time commas have anything to do with breathing is when something is going to be sung. Unless you are planning for someone to sing your academic paper or dissertation, then base your comma usage on sentence structure, not on projections of when a hypothetical reader needs to breathe.

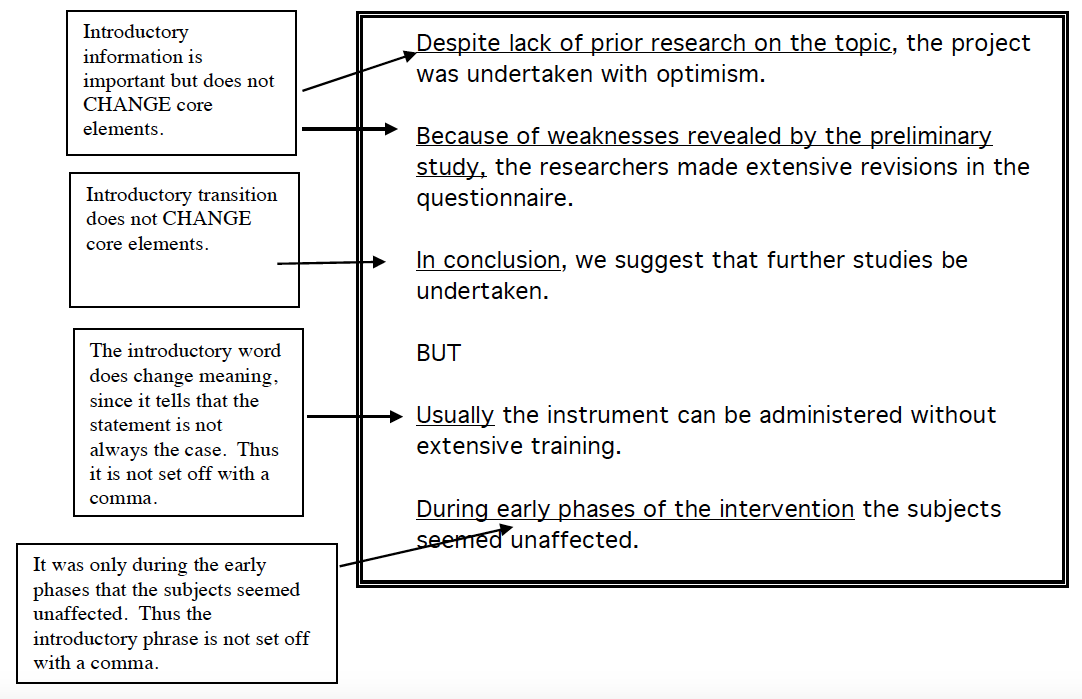

Use 1: Use a comma to set off an introductory element. This usage relates to the principle of setting off elements that distract from the sentence core. The comma after an introductory element tells the reader that you are finished with the introduction, and the core is coming up.

Use 2: Use comma(s) to set off nonrestrictive elements. This rule simply puts terminology on a principle already established and emphasized.

- Nonrestrictive means that something does restrict or change. A nonrestrictive element, though it may convey important information, doesn’t actually change the core elements.

- Restrictive means that something does restrict or change. Information that interrupts in the middle or tags on at the end and does not change or restrict the core elements is set off by comma(s). Information that actually changes elements in the core is considered to be bound into the core and therefore is not set off by commas.

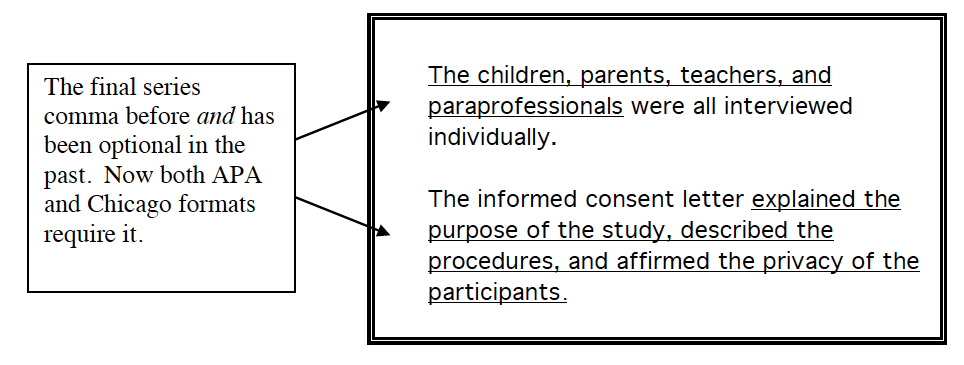

Use 3: Use commas between items in a simple series of three or more. Ah, a rule that’s fairly easy. A simple series is one that does not contain commas within the series items

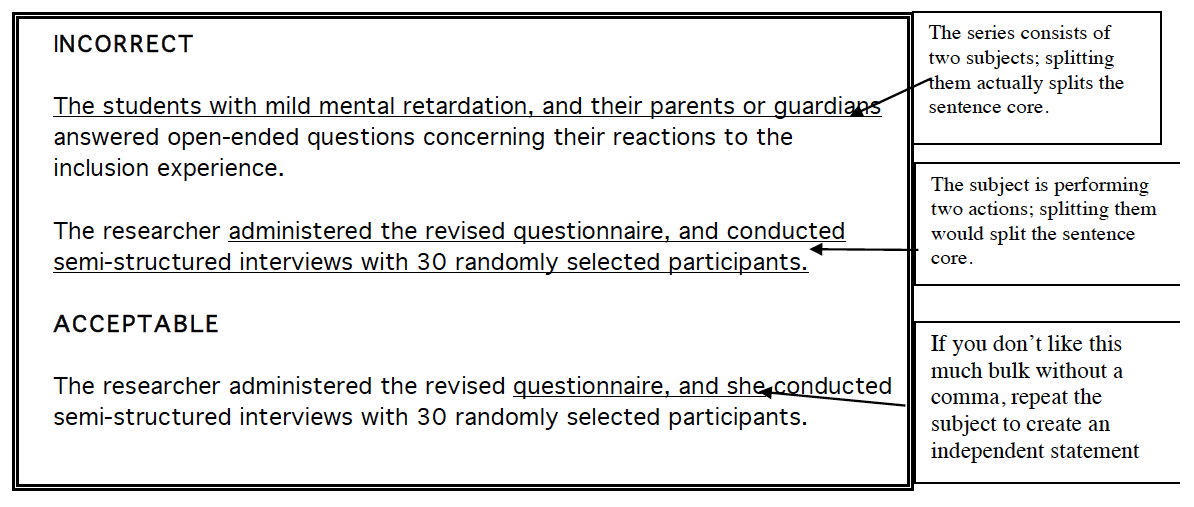

Misuse 1: Do not use a comma when it would separate core elements (subject and verb, verb and object, or verb and complement). Add to this preposition and object.

Misuse 2: Do not use a comma between items in a series of two. The pair of items functions as a unit, so they should not be split. In effect, splitting them creates a false intersection.

A Comma Plus a Coordinating Conjunction Changes the Blinking Yellow Light to a Blinking Red Light

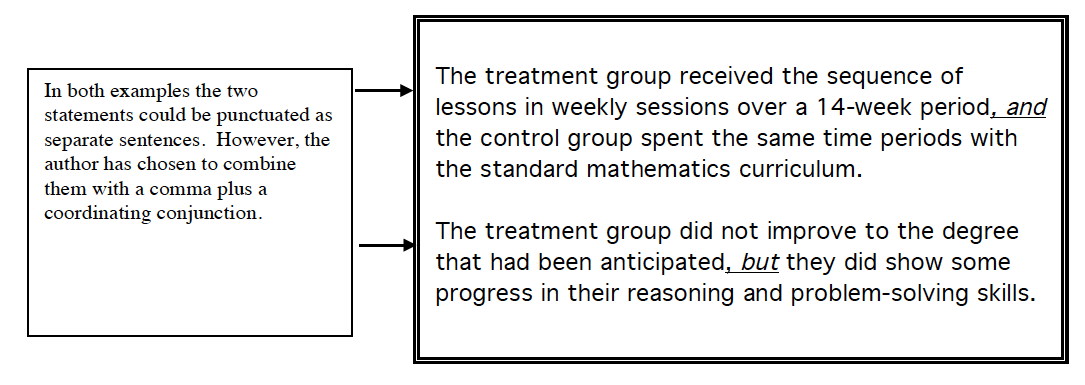

When traffic becomes heavier and a complete stop is necessary before proceeding into the intersection, the blinking yellow light may be changed to blink red. This signals a brief complete stop. A comma combined with a coordinating conjunction (and, but, for, or, nor, yet, or so) is like changing the blinking yellow light to blinking red. It signals a brief but complete mental stop.

The comma plus coordinating conjunction is used to join independent statements (clauses) into one sentence. The stop needs to be complete because a whole new core is coming up.

- A comma alone is not enough to join independent statements. The error of using the comma alone between independent statements is called a comma splice. It is considered a serious error.

- A coordinating conjunction alone is not enough to join independent statements. An and, but or other coordinating junction (for, or, nor, yet, so) without a comma signals a continuation of the last statement, not a new one.

A Semicolon is a Stop Sign

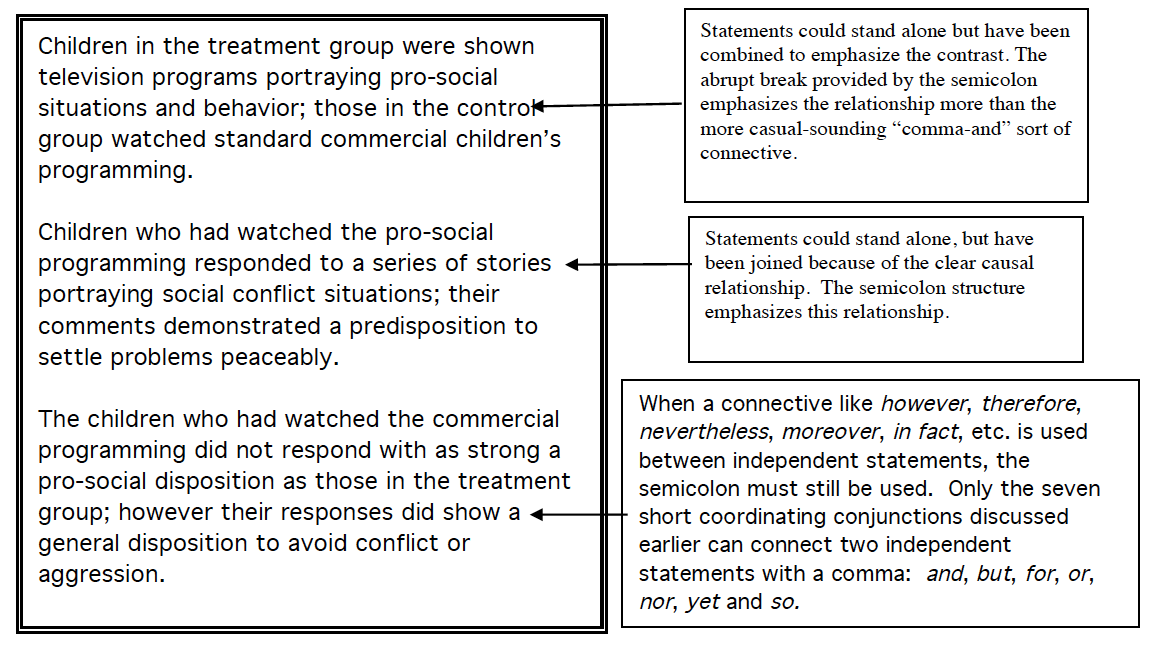

A semicolon is the stop sign of punctuation: It signals a brief but complete stop. Its most common use is between independent statements when there is no coordinating conjunction. Yes, the semicolon is equivalent to the comma plus coordinating conjunction, just as a stop sign is equivalent to a blinking red light in what it signals the driver to do.

Use 1: Use a semicolon between independent statements (clauses) when there is no coordinating conjunction.

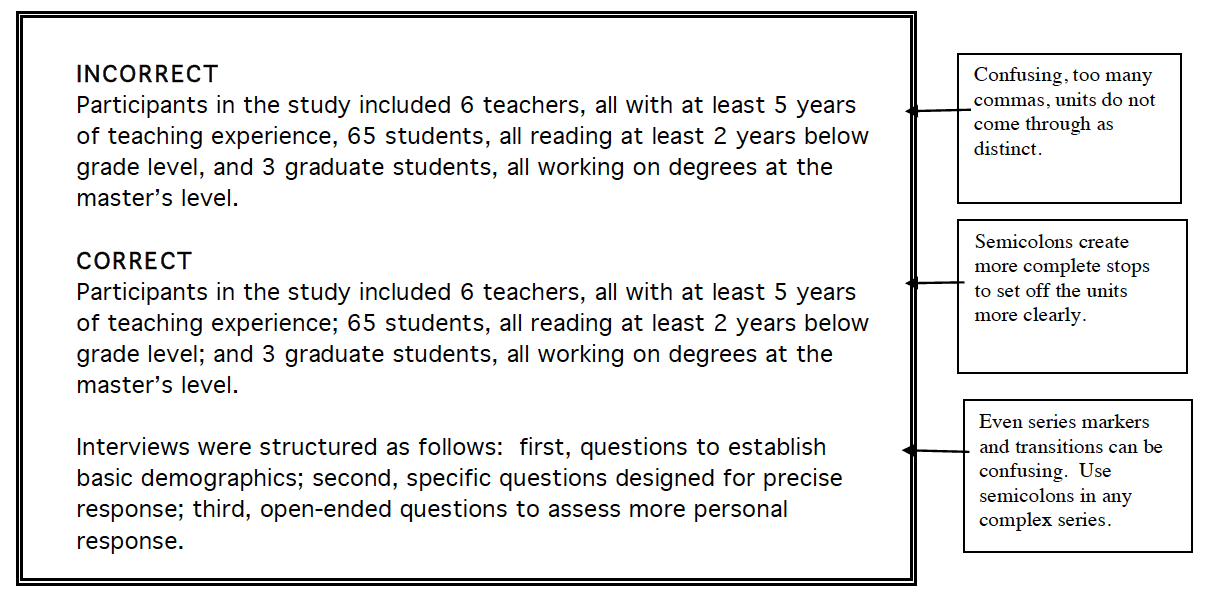

Use 2: Use semicolon to separate items in a complex series. A complex series is one that contains items that have commas within them. A stop signal is needed to keep these items from running together.

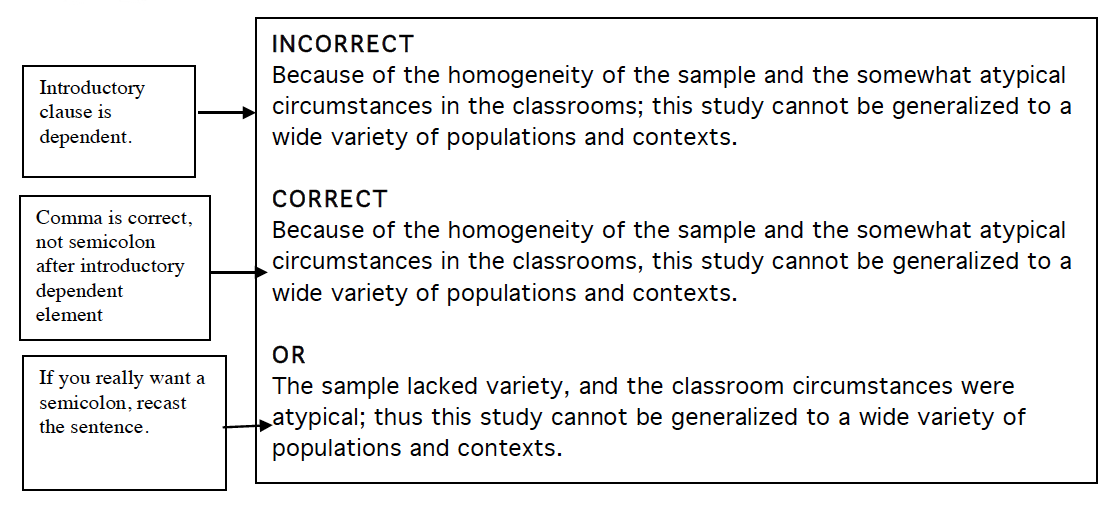

Misuse: Never use a semicolon between dependent and independent elements.

The Colon is a Green Light

The colon is punctuation’s green light. It signals an important intersection, but it tells you to keep going rather than stop. Although the basic sentence core is completed, there is something ahead that you need in order to understand it accurately.

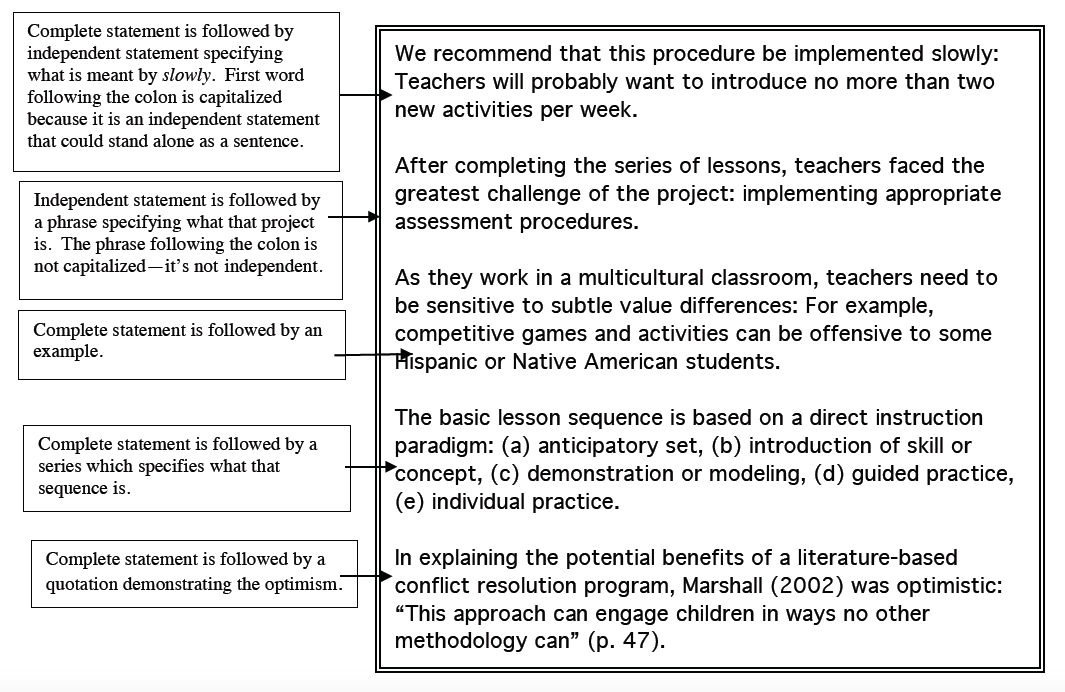

Use a colon to connect explanatory information to a completed sentence core.

Two conditions are necessary in order for a colon to be correct.

- It must be preceded by a complete statement (sentence core).

- It must be followed by a sentence element that explains, expands, exemplifies, or specifies the preceding statement. You should be able to mentally insert one of the following:

- namely

- specifically

- as follows

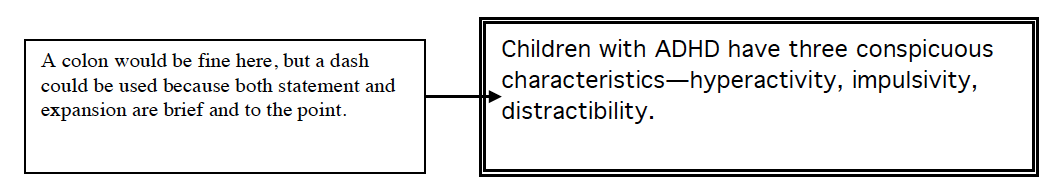

A Dash is a Construction Flare

A dash can be compared to a construction flare. A dash or pair of dashes warns the reader that something is broken up or diverted. Dashes can call special attention or give a casual tone to what you say (but not in your dissertation, of course).

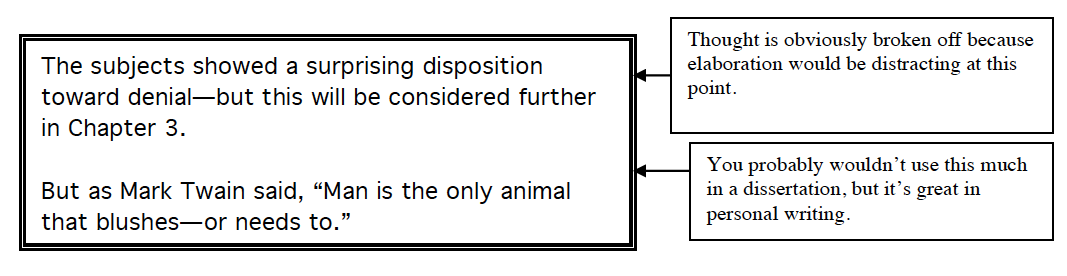

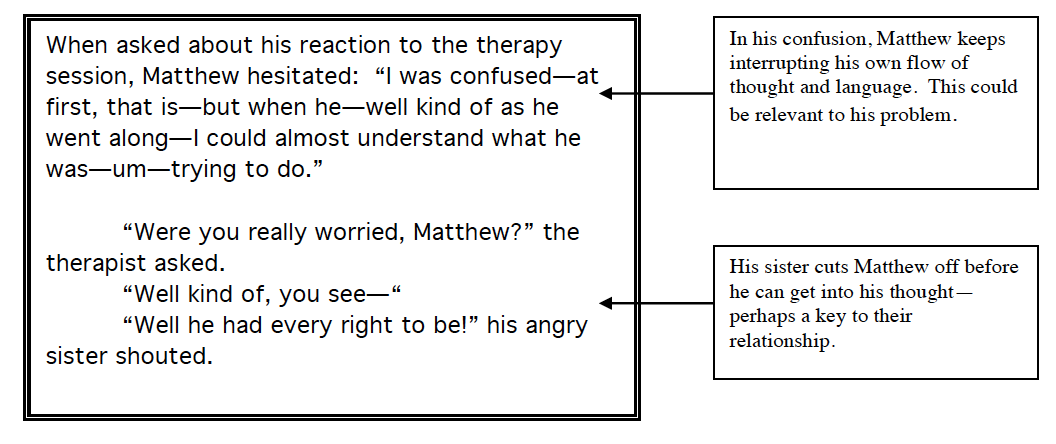

Use 1: Use a dash to indicate an abrupt shift in meaning or tone.

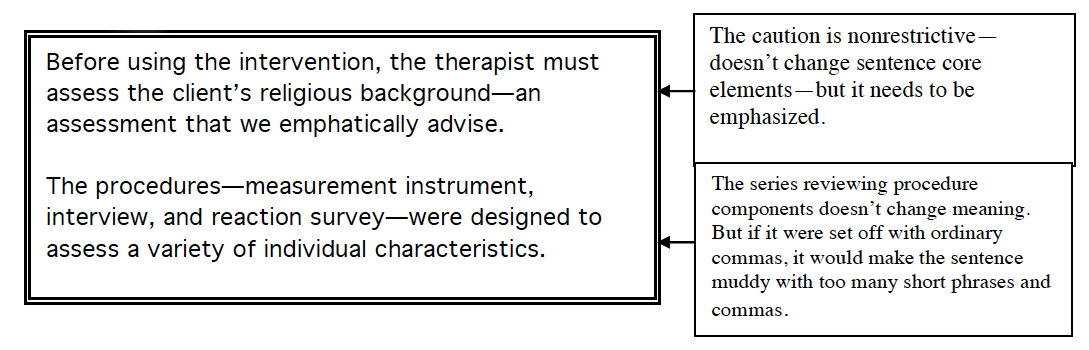

Use 2: Use a dash or pair of dashes to set off a nonrestrictive element that needs special emphasis or clarity.

Use 3: You may use a dash in place of a colon if the elements are short or the tone is informal.

Use 4: Use a dash in dialogue or other forms of transcribed oral communication to indicate interruption—of oneself or of someone else.

Misuse: The main misuse of dashes is overuse. The dash can be a very important mark of punctuation if you do not compromise its potential for emphasis by overusing it.

Step 5: Trimming

Steps for Trimming Fat

First, determine who did what and how, aligning the most important information with the sentence core. More words are required to edge information in around the core than to use it correctly. Like inexperienced bakers who may fill the sagging middle of a cake with extra icing, when you don’t get the basics in place, you usually end up loading on too much.

OBESE

It was the stated opinion of the therapist that the state of depression experienced by the young women could be attributed to the fact that they did not receive adequate encouragement from their parents.

- Who is acting here? The parents actually seem to be the ones at fault, even though they are buried at the end of the sentence.

- What are they doing? Failing to encourage their daughters?

- What resulted? Depression, according to the therapist.

More Trim

The parents were failing to give their daughters adequate encouragement, resulting in the young women’s depression, explained the therapist.

- Occasionally you need to emphasize outcome rather than agent, thus you could make depression the subject of the sentence (ex. 1 below).

- You could put the therapist in an introductory rather than a concluding element if you want to draw more attention to the source of the opinion (ex. 2 below).

Alternatives

1. The young women’s depression seemed to be caused by inadequate parental encouragement, noted the therapist.

2. According to the therapist, the young women suffered depression due to inadequate parental encouragement.

Second, get rid of redundancy. We all tend to bloat our sections and even our paragraphs by saying things more than once to be sure they are said. Unfortunately, we tend to do this to our sentences as well. We just don’t realize that we do it. Once you get your basic structure in place, you don’t need extra layers and flourishes. Generally they just confuse things. In writing, simple and palatable is better.

OBESE

It was evident that the symptoms that they showed included that they were discouraged in their outlook, self-centered in their behavior, and unmotivated in their undertakings, resulting in signs of classic depression which they experienced.

- If it weren’t evident, the researchers wouldn’t be reporting it.

- Discouragement is an aspect of outlook, self-obsession is a form of behavior, and motivation requires something to be unmotivated about. So these are redundancies (like “small is size” and “red in color”).

- Symptoms are things that are shown.

- The fact that they are experiencing symptoms doesn’t need to be expressed twice.

REDUCED

It was evident that their symptoms that they showed included that they were being discouraged in their outlook, self-obsessed in their behavior, and unmotivated in their undertakings, resulting in signs of classic depression which they experienced.

REDUCED FURTHER

Their symptoms of classic depression included discouragement, self-obsession, and lack of motivation.

Third, avoid twisting words out of their natural usage so that you need extra words to get them to function. Identify what is really functional and how it needs to function. Twisting or elaborating things to be fancy generally (usually) just confuses them. Also avoid stretching words into phrases.

OBESE

The implementation of the strategic procedure was operationalized through the instrumentality of collaborative groupings of cooperative nature representing unification of diverse entities.

- Begin by letting the air out of some of these overblown words and phrases.

- Let verbs be verbs and nouns be nouns etc. Avoid distortions like operationalized, instrumentality, and unification: operate and unify are verbs; instrument is a noun.

REDUCTION PROCESS

The implementation of implemented the strategic procedure strategy was operationalized was operated through the instrumentality of by or though unified collaborative groupings groups of cooperative nature representing unification of diverse entities.

REDUCED

The strategy was implemented by unified collaborative groups.

Common Sources of Sentence Calories

Avoid piling on sugary fluff in the form of unnecessary adjectives and adverbs. Many of us damage our positions by overstating them with descriptive words. A simple, clear statement will have more impact on a critical reader than an inflated one.

- Concerning adjectives, Mark Twain advised, “When in doubt strike it out” (as qtd. by Trimble, 2000, p. 77).

- As far as adverbs are concerned, writing guru John Trimble (2000) remarked, “Minimize your adverbs . . . especially trite intensifiers like very, extremely, really, and terribly, which show a 90% failure rate” (p. 77).

OBESE

It is extremely important to recognize the very significant and costly weaknesses of the study, which really show terribly inconsistent procedures on the part of the research team.

REDUCED

Scholars must recognize inconsistency in the procedures, which weakens the study.

Avoid fattening phrases that provide less nutrition than their simpler alternatives.

|

Problem

|

Category

|

Typical Examples

|

|

Words used as wrong part of speech

|

verb to noun

|

to implement/implementation

to contain/containment of

to assign/assignation of

to characterize

/characterization of

|

| |

noun to verb

|

operation/operationalize

context/contextualize

margin/marginalize

strategy/strategize

institution/institutionalize

|

| |

adjective to noun

|

minimum/ minimalization

better/betterment

|

|

Superfluous phrases

|

false core

|

It is a fact that

It can be discerned that

There has been an observation

that

|

| |

redundant classification

|

small in size, red in color

tedious in nature, despondent in mood, behaviorist in orientation, period of time

|

|

Extra words

|

immediate restatement

|

necessary essentials, basic foundation, honest truth, unique individuality

|

| |

phrase instead of word

|

“due to the fact that”/because

“at the time that” or “during the period that” /when

“in a manner similar to”/like

|

The most important aspects of writing your paper, thesis, dissertation, or article are understanding your information and dealing with it thoughtfully, accurately, and creatively. Your chair and your committee will guide you with these aspects. Your sentences are just your medium for conveying the content. But the medium can betray your efforts if you are not able to use it competently.

As with the organizational and paragraph strategies discussed in the previous chapter, the techniques, strategies, practices and rules discussed here may seem like a lot to apply. Actually they are. But they become more natural and later semi-automatic as you get used to them. Refer to this set of instructions when you need to.

Crafting effective sentences doesn’t have to be a mysterious process. Just remember the basic steps, and you should be able to solve and present your cases effectively:

- Get in step

- Make your case

- Punctuate for clarity

- Apply specific (punctuation) rules

- Trim down

Keep professors, editors, deans, and other such critics off your case!