This chapter was first published as an EDUCAUSE blog article on September 10, 2020, under a Creative Commons license (BY-NC 4.0), with the title Dear Professors: Don't Let Student Webcams Trick You. It is reprinted here with the permission of the authors.

During the spring 2020 semester, when higher education quickly shifted to remote online teaching in response to the coronavirus pandemic,1 faculty and leadership didn't have much time to think carefully about the many details of teaching online. Now that the spring and summer semesters are behind us and we are facing remote teaching during the fall semester and possibly beyond, some faculty members may question whether to require all students in live online classes to be on webcam all the time. As experienced online educators, our answer is no for four reasons.

First is the issue of equity. Online classes with heavy webcam use require faster internet connections and newer computer equipment, and not every student is on equal footing in this regard. For example, some students report tech access problems such as "slow, rural internet." One student said, "[My] internet connection isn't strong enough to support me using my video. When I do, I am often kicked out of the Zoom classroom and have to reenter." Another student described the following untenable situation: "If I need video, I have to set up my decade-old personal computer, which is old and slow and acts like it is going to die any day now." In addition, requiring students to broadcast their homes to their classmates can bring socioeconomic differences to light, including details that students may prefer to keep private.2

Second, constantly being on webcam can detract from student learning. Having all students on webcam invites many distractions that can split students' attention, including a preoccupation with looking at themselves on screen, feeling pressure to perform for the instructor, watching other students' behavior, and looking at other students' home environments. It's difficult to focus on the instructor when classmates are doing things like eating messy meals, constantly shifting and moving, managing children, picking their noses, using the restroom, or sitting in a glorious sunny backyard. There's a reason many of us are tired of Zoom. According to an article published in The New York Times, "the distortions and delays inherent in video communication can end up making you feel isolated, anxious, and disconnected."3 In addition, if students don't want to be on webcam and are forced to do so, they may feel resentment, and if students are required to be on webcam while experiencing illness or grief, they may feel dehumanized. One student noted that the instructor "often tells us to turn on cameras without citing [a] reason. I don't think it's necessary because there are things that may occur in my remote experience at home that may be distracting to me, and I want to limit that to myself (for example, parents and pets often barge in, there's decoration in my childhood home that is rather embarrassing and unprofessional, and there is no option to go to a library or other setting, etc.)." Feelings of resentment and embarrassment can distract from learning. Conversely, allowing students to choose whether or not to be on webcam is an example of trauma-informed teaching—"an approach to college curriculum delivery that involves adopting a set of trauma-informed principles to inform educational policies and procedures."4

Third, requiring students to be on their webcams during class poses risks to good teaching. Instructors risk cognitive overload if they try to pay attention to all of their students' webcams while simultaneously focusing on teaching the class. If the instructor incorrectly perceives passive student webcam presence as interaction, they may focus less on incorporating meaningful interactive learning activities because they think that there is no need to do so. This is not exclusive to remote learning. Carl Wieman—a Stanford University professor who is a leader in the use of experimental techniques to evaluate the effectiveness of various teaching strategies for physics and other sciences—said that approximately one thousand research studies confirm that active learning strategies consistently result in greater learning and lower failure and dropout rates than lecture-based teaching.5

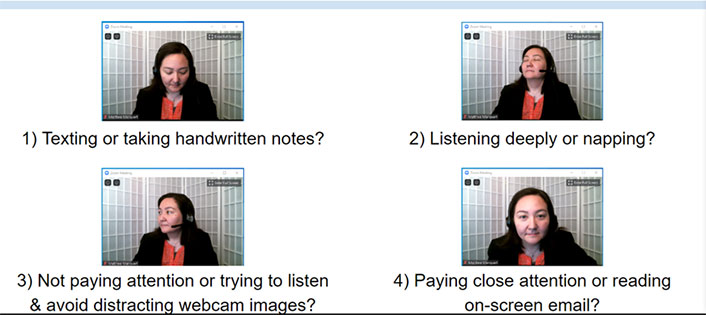

Fourth, requiring all students to constantly be on webcam does not provide the benefits that proponents imagine it would, as human instructors cannot monitor twenty or more webcam images at once. Students as young as ten years old know how to fake their webcam presence, making it unreliable for enforcing attendance.6 Requiring students to be on webcam is not a reliable way to make sure that they are paying attention, as not everyone looks the same when they are learning, and instructors may have paradigmatic, prescriptive, and causal biases regarding what counts as learning behavior.7 For example, each image in figure 1 could be interpreted differently.

Figure 1. These examples show why interpreting a student's body language (as seen through a webcam) can be difficult.

Figure 1 Alt-Text. This figure includes four images of one of the authors on webcam; they demonstrate the difficulty of interpreting body language on webcam. The first image is the author looking down, with the text "Texting or taking handwritten notes?" The second is the author looking up with eyes shut, with the text "Listening deeply or napping?" The third is the author looking to the side, with the text "Not paying attention or trying to listen & avoid distracting webcam images?" The fourth is the author staring closely at their their computer screen, with the text "Paying close attention or reading on-screen email?"

The Benefits of Using a Webcam

For those who would point out that there are many benefits to using a webcam, we agree. Students in online programs feel like they are part of a community when they are able to see each other face-to-face, and pet appearances on webcams are what carried many of us through our spring web conferences.

Furthermore, students who are attending remote online classes from locations all over the world can bring their disparate locations into the classroom every day. This new experience of place can energize the curriculum. A pedagogy of place can be used to build on the critical work we must do to counter structural racism and exclusion. But cameras are not the only way to bring student presence into the online classroom.8 One student suggested that educators "encourage people to put on cameras during the group breakout sessions and facilitate discussions so that all members participate. Otherwise, it ends up being the TA and one other student with their camera on working on what is supposed to be a group project while everyone else is silent."

We recommend that instructors stay on their webcams throughout the class and plan selective use of students' webcams for activities such as group discussions, role-play activities, debates, panel discussions, student presentations, and any other interactive activity that would be enhanced by seeing the students who are speaking. Even in those cases, if a student cannot be on webcam, participation via microphone or typed chat can suffice. Allowing these less bandwidth-intensive forms of participation is essential for equity. For example, the Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice surveyed 38,000 students this spring and found that 11 percent of white students and 17 percent of Black students do not have sufficient internet access.9

Tips for Optimizing Webcam Use

To get the most out of webcam use, instructors should be thoughtful about their webcam setup and optimize their lighting. Good lighting is just one of the tools instructors can use to enhance their online presence and make their classes more engaging.10 Instructors should ask students to be ready to activate their webcams as needed. We also recommend incorporating a variety of interactive elements—such as typed chat, formal and informal polling, on-screen drawing, live note-taking pods, and breakout rooms—to help ensure that live online classes are so engaging that instructors don't need to see students on webcam to know that they are present and learning.11

Instructors who are planning to use student webcams in live online classes should consider the following questions:

- Is there a student-centered reason for the use of webcams in this activity?

- Are there other ways to actively engage students in meaningful learning throughout the class?

- How will I accommodate students who cannot be on webcam?

- Have I considered equity and inclusion in designing my activities?

These types of questions should also be applied to decision-making about presence for in-person classrooms. Good teaching is good teaching, regardless of how instruction is delivered. For example, passive student presence in any context may detract from teaching and learning, as described above. As educators who are beginning a fall semester that requires the flexibility of remote teaching, we should all reflect on the underlying rationale for what may be ingrained teaching habits rather than sound pedagogical practice.

Notes

- The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic during a media briefing on March 11. See Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, "WHO Director-General's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19," March 11, 2020.

- Nicholas Casey, "College Made Them Feel Equal. The Virus Exposed How Unequal Their Lives Are," The New York Times, April 4, 2020.

- Kate Murphy, "Why Zoom Is Terrible," The New York Times, April 29, 2020.

- Matthea Marquart, Janice Carello, and Johanna Creswell Báez, "Trauma-Informed Online Teaching: Essential for the Coming Academic Year," The New Social Worker Magazine, July 6, 2020.

- Carl Wieman, "Taking a Scientific Approach to Teaching," (keynote address Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning 2019 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium, New York, NY, March 12, 2019).

- Angie Maxwell, "Found the kid playing with her dog instead of Zooming with her teacher. She told me not to worry. She took a screenshot of herself 'paying attention,' then cut her video & replaced it with the picture. 'It's a gallery view of 20 kids, mom. They can't tell.' She is 10. #COVID19," Twitter, April 14, 2020; Samantha Cole, "People Are Looping Videos to Fake Paying Attention in Zoom Meetings," Vice, March 23, 2020.

- Stephen Brookfield, "The Getting of Wisdom: What Critically Reflective Teaching Is and Why It's Important," in Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

- David A Greenwald, "The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place," Educational Researcher 32, no. 4 (2003): 3–12.

- #RealCollege During the Pandemic, research report, (Philadelphia, PA: The Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, June 2020).

- Kristin Garay, Matthea Marquart, Rebecca Y. Chung, and Johanna Creswell Báez, "Lighting and Webcam Setup for Teaching Online Classes," Columbia University Libraries (website), May 13, 2020. See also Agata Dera, "The Power of Lighting in a Virtual Classroom: Tips on Improving Webcam Lighting for Online Educators," Teaching and Learning in Social Work (blog), March 16, 2020.

- Matthea Marquart, "Strategies for Successfully Engaging All Students in Live Synchronous Online Classes," (poster presented at the Columbia University Center for Teaching and Learning 2017 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium, New York, NY, March 6, 2017); Matthea Marquart, Michael Fleming, Sam Rosenthal, and Melanie Hibbert, "Instructional Strategies for Synchronous Components of Online Courses," in Steven D'Agustino, ed., Creating Teacher Immediacy in Online Learning Environments (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2016), 188–211; The Columbia School of Social Work has developed a free recorded webinar series and an associated Google doc to help instructors prepare to use web conferencing tools such as polling and chat to engage students.