This report presents a review of study abroad research conducted from an ecological perspective (Kramsch, 2003; Leather & van Dam, 2003; van Lier, 2004) and identifies areas of inquiry that are lacking compared to second language acquisition and other fields (i.e., linguistics, psychology). It

identifies value-based views as a high-priority area of interest and draws on frameworks in other fields to outline how language learning research could effectively describe the moral ecology of study abroad for language learning.

Language learning research over the last two decades has increasingly turned to an ecological perspective to make sense of the wide variety of learner experiences across different contexts. Several edited books laid a foundation for ecological research in second language acquisition (Kramsch, 2003; Leather & van Dam, 2003; van Lier, 2004), and literature reviews since then have provided updates on the recent undertakings of the ecological movement (Kramsch & Steffensen, 2008; Steffensen & Kramsch, 2017). An ecological perspective of language learning is distinguished by its focus on complex relationships that exist between learners and their environments, as opposed to the isolated, internal workings of individuals’ minds or the simple cause-effect relationships of external forces. Researchers have taken up this approach to provide holistic descriptions that generate new understandings of the learner experience. The result has been the deconstruction of prior assumptions about the process of language acquisition and socialization, agency, and other key concepts commonly considered in second language acquisition research. Language practitioners use the results of ecological research to design experiences that address the complexity of “whole people” learning a language within their “whole lives” (Coleman, 2013).

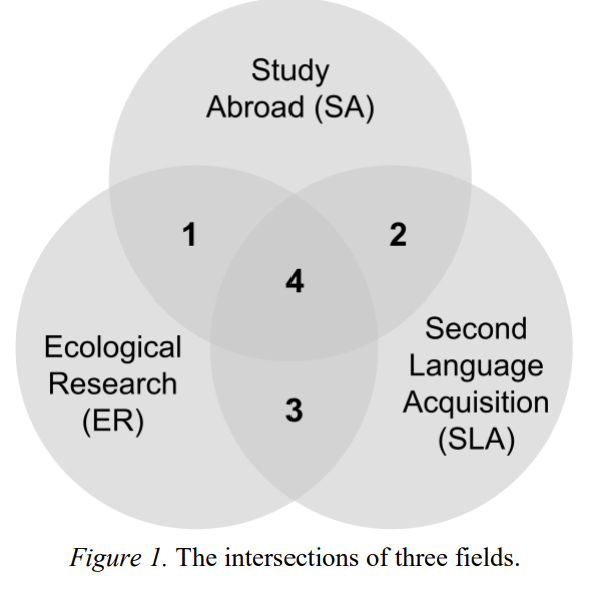

Ecological perspectives have started to affect language research specific to study abroad. At a time when “there is little consensus still on how to best define studying abroad and how to best study its effects” (McKeown, 2009, p. 106), framing study abroad in ecological terms has helped reframe concepts such as the study abroad context, participants, and the goals of study abroad. This has resulted in numerous field studies describing the relationships between diverse learners and diverse foreign contexts. However, while ecological research in the field of second language acquisition has been repeatedly reviewed (Area 3 in Figure 1), ecological research specific to study abroad for language learning (Area 4 in Figure 1) has yet to be reviewed and summarized, which could provide field-specific insights and reveal areas for further inquiry.

Additionally, ecological study abroad research stands to benefit from other fields of inquiry. So far it has drawn heavily on language research in non-study abroad contexts (e.g., SLA, sociolinguistics), but an ecological perspective also demands the consideration of other fields, since learners’ environments do not consist only of social and linguistic forces. Steffensen and Kramsch (2017) suggest that practitioners should “supplement their linguistic and sociocultural expertise with input from psychology, cognitive science, and the life sciences” (p. 23). Other disciplines can provide ideas and frameworks for answering questions about study abroad that have already started to be addressed in other fields.

In light of these needs, this paper (a) summarizes recent applied research that has taken an ecological approach to study abroad, (b) proposes future directions for ecological study abroad research in light of recent trends in SLA, and (c) presents a value-based approach to ecological research using insights from other fields.

Defining Ecology

An ecology of language learning draws on the image of a biological ecology: an expansive consideration of the organisms and aspects of an environment, with a focus on the relations of organisms to one another and to other aspects of the environment. Here each part of the ecology of study abroad for language learning is briefly defined: the environments, the people studying abroad in those environments, and the variety of relationships they have with aspects of the environment.

First, environment denotes the broad collection of physical and social resources that people live around. Study abroad research has often referred to “the study abroad context,” but this paper will use “environment” to emphasize the ecological metaphor. The most obvious resources in an environment are often physical and close in proximity (e.g., a café down the street), but resources can also be social (e.g., discussing politics with a friend at said café) or physically distant (e.g., reading a message from a friend living far away).

Second, different terms have been used to describe people studying abroad. Referring to them as language learners, students, or participants is applicable in many cases, but from an ecological perspective these names focus too narrowly on an individual aspect of the whole person who studies abroad. For this reason, this report will refer to the protagonist of the reviewed research as the “sojourner,” a broader term denoting someone who resides temporarily in a foreign place.

Lastly, the relations that sojourners have within their environments are referred to as “affordances.” Resources in an environment are not affordances in themselves, but they afford certain opportunities for action to sojourners. They are the ways that things, people, symbols, and ideas show up to sojourners. In his 2004 work, van Lier adds that “what becomes an affordance depends on what the organism does, what it wants, and what is useful for it” (p. 252). Affordances are just as much about the sojourners as they are about the resources.

REVIEW OF ECOLOGICAL STUDY ABROAD RESEARCH

The first step in summarizing ecological research is defining what qualifies as ecological enough for consideration. In a similar review of study abroad (SA) research related to language socialization, Kinginger (2017) found that many qualitative studies reported results that contributed to a socialization perspective, but few studies took on socialization as their primary framework. The same can be said of ecological perspectives in study abroad; a number of qualitative studies have characteristics of ecological research, but few discuss their questions or present their results in an ecological perspective outright. To identify which reports qualified as ecological research, this review uses the characteristics of ecological research

identified by Steffensen and Kramsch (2017) as criteria for inclusion:

(1) the emergent nature of languaging and learning; (2) the crucial role of affordances in the environment; (3) the mediating function of language in the educational enterprise; and (4) the historicity and subjectivity of the language learning experience, as well as its inherent conflictuality. (p. 28)

For the sake of space, readers who are unfamiliar with these terms should see Steffensen and Kramsch (2017) for an in-depth definition of each of these criteria.

After identifying these criteria, database searches for English, peer-reviewed publications within Google Scholar, EBSCO, ERIC, and individual journals created a pool of 92 publications, including articles, books, and chapters from edited volumes. These were found using search terms that included variations of the criteria (e.g., subjectivity, subjective, learner perspective) and “study abroad.” Reverse searches of highly cited articles were also conducted using the same strategy. Finally, each publication was reviewed to see if it was theoretically consistent with all four criteria, regardless of whether keywords were included or not. This resulted in 54 publications for inclusion in the summary. After summarizing each publication individually with regard to the criteria, insights were combined across publications and organized temporally as they might apply to a sojourner. The themes that emerged (see Figure 2) describe sojourner experiences from an ecological perspective: (1) the interaction of sojourner and prior environments, (2) the interaction of sojourner and foreign environments, (3) perceiving affordances of the foreign environment, (4) acting on affordances, and (5) the negotiation of difference.

The Interaction of Sojourner and Prior Environments

In order to make sense of what happens during study abroad, ecological research has considered how sojourners have interacted with their environments before going abroad. These interactions were as diverse as the sojourners, since sojourners’ personal characteristics (e.g., gender, nationality, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, spirituality, religion) interacted with all the unique aspects of prior environments. Research so far has focused on macro-level discourses in which sojourners are embedded before going abroad (e.g., globalization, American exceptionalism, Confucianism, Buddhism, feminism, nationalism). These discourses are composed and communicated to sojourners (often implicitly) by many actors, including governments, businesses (Jang, 2015), and professional organizations that influence or prescribe standards for language learning; educational institutions that influence and implement policy through curriculum; families and peers who interact most often and closely with would-be sojourners; and a myriad of other groups and individuals who interact with the would-be sojourner through service encounters or informally by being nearby.

While it is probably accurate to say that sojourners are more familiar with prior environments than the foreign environments in which they study, they may not be comfortable with or conform to the norms of prior environments, even if they have spent their whole life in a “home” environment with a monolithic cultural view. The discourses that permeate prior environments do not determine sojourners’ perspectives and values, but sojourners do act in relation to them, whether in favor, against, or in some other way. As sojourners travel from one environment to another, the ways that they interacted with aspects of prior environments go with them, so to speak, and inform their interactions within new environments.

For example, Diao and Trentman (2016) saw that some Americans who sojourned in China and Egypt struggled to think of themselves and their studies in ways that did not propagate American political and economic influence. Even those who might have been openly critical of American hegemony “failed to see the connection between the macro discourses they drew upon and the West’s continued power and dominance over the nonWest” (p. 47). Even if they can identify some of them, sojourners still may not understand that aspects of their prior environments (e.g., the macro discourse of American exceptionalism) color what they see, do, and become in another environment.

The Interaction of Sojourner and the Study Abroad Environment

Ecological study abroad research reveals that the epicenter of potential cultural, linguistic, and personal growth on study abroad lies at the interaction of the sojourner and aspects of the study abroad environment. Upon arrival the sojourners’ personal characteristics and histories interact with the macro-level discourses and ideologies of the foreign environment. For example, in Jin’s (2012) case study of Chinese compliment response strategies, having a Chinese mother seemed to motivate one sojourner to adopt Chinese strategies instead of Western ones (for similar examples, see Kinginger, 2004; McGregor, 2016; Patron, 2007; Pipitone & Raghavan, 2017). These interactions are often similar to those in prior

environments since they are influenced and communicated by similar actors, but substantial differences between old environments and the new can make it difficult for sojourners to act with the same competence and confidence as before (Jackson, 2011).

Not only can new discourses cause discomfort, but discourses from prior environments might become unfamiliar again in the foreign environment. For example, sojourners might go abroad with the intent to become global citizens, transcending one nation or culture. However, sojourners sometimes find that globalization requires more than they are willing to give, as they experience feelings of uprootedness, and rethink taking on a new identity. For example, Bae and Park (2016) described Korean families living abroad who were committed to helping their children develop international competencies, but who also became deeply concerned that their children were losing their Korean identity in the process. Globalization and other ideas can be comfortable in one environment, but become problematic once sojourners become more familiar with how they play out in real life.

Perceiving Affordances of the Study Abroad Environment

At the moment of interaction in a foreign environment, affordances emerge that guide sojourners’ actions. The most widely discussed affordances of study abroad are associated with interactive contact with L2 speakers (Allen, 2010a; Brown, 2014; Liu, 2013; Siegal, 1995; Shively, 2010, 2016; Trentman, 2013; Umino & Benson, 2016). Researchers reported various kinds of interactive contact, including with host families or roommates, professional and educational socializing, service encounters, informal conversations with strangers, interest group activities, individual friendships and social circles, and even romantic relationships.

It is commonly thought that interactive contact is ideal for developing cultural and linguistic competence, and as such, study abroad programs have sought to expand opportunities for sojourners to have more of it. However, Allen (2010a), Benson (2012), Kinginger (2010), and Trentman (2013) take an ecological perspective and refute the assumption that useful affordances emerge simply when some level of access is provided to new resources. They argue that affordances emerge for sojourners acc ording to how resources align with their abilities, interests, and the stories they tell to make sense of events. For example, host families or roommates can be physically present yet practically invisible to the sojourner as a linguistic resource. A university campus nearby with thousands of potential speaking partners might only draw the attention of the most outgoing sojourners. Proximity does not, by itself, lead to engaging interactions with L2 speakers, but requires an alignment of interests (Trentman, 2013; see also Peirce, 1995) and other qualities between L2 speakers, sojourners, and the environment where they interact.

Aligning resources in a SA environment with sojourners can be difficult if study abroad programs oversimplify sojourners’ characteristics. For example, even in programs in which the primary focus is on language learning, not all sojourners position themselves as “language learners” (Kinginger, 2008). Researchers have described sojourners with many different orientations to language learning while abroad. In a general way, sojourners sense whether learning the L2 has imminent value for them or not (Allen, 2010c). Upon deeper reflection, they may realize that the value of learning the L2 comes through professional qualification (Jang, 2015), fulfilment of academic requirements, cultural curiosity (Bird, 2021), or societal advancement. In other words, it is an oversimplification to classify sojourners as merely language learners. They bring other motives with them that are primary to language learning. The L2 is often instrumental to other goals, and if resources are not properly aligned, sojourners may despair or find other ways to reach their goals than through linguistic or cultural advancement.

Another affordance sometimes taken for granted but often discussed in ecological research is the relationship between sojourners and language itself. Language is a necessary but imperfect tool for creating bridges of understanding (Kinginger, 2015; Tan & Kinginger, 2013), entering into social activities (Kinginger & Belz, 2005; Kinginger et al., 2014; Kobayashi, 2016), and mediating the creation of new sojourner identities (Benson et al., 2012; Diao, 2017); Language is value-laden (van Lier, 2004), meaning that those who use it have to deal with the social norms, value systems, and history related to the language. The act of choosing to use (or not use) language can be full of meaning beyond what is said or written. Even when sojourners interact with others without apparent linguistic difficulty, their acts might carry relevance or values that they did not expect. In Brown (2014), Julie thought that she was only being compassionate and helpful when she decided to sit by and interact with an isolated male student in her class. However, a misunderstanding with a different male outside of class made her change where she sat, as she feared that the isolated student might understand her compassion as romantic interest.

Instances like these are symbolic misunderstandings, pragmatic failures to communicate one’s intentions and meaning. These misunderstandings may come about because of a lack of familiarity with the values involved in certain actions in a foreign environment. The more familiar sojourners become with these values generally and how people act on them, the easier it may be for them to see how L2 native speakers signal their positions within those systems and see how they can position themselves as well. As they become more familiar with the implicit values that language conveys and the discourses that frame those values, sojourners develop symbolic competence and can present themselves more intentionally and accurately in the foreign environment. Sojourners in Shively (2018) found ways to portray themselves as they wanted to be seen after they became more familiar with humor in the foreign environment. Jared, for example, used teasing to portray himself in a masculine way to his peers. He and others increased “their ability to accomplish communicative goals such as being funny and enhancing solidarity through humor” (p. 241).

Acting on Affordances

The language, interactive contact, and many other aspects of the study abroad environment present unique affordances to individual sojourners that enable action. Sojourners’ growth depends on how they act on these affordances, but what actions they may take is difficult to foresee, even for sojourners themselves.

Much of the research has described various approaches to study abroad that seem to dispose sojourners towards certain actions. These approaches might be described as basic strategies for interacting with aspects of the study abroad environment. For example, some sojourners have actively avoided the discomfort of foreign cultures by seeking out familiarity abroad through compatriot socializing or communications with friends and family at home (i.e., an avoidance strategy; Wilkinson, 1998, p. 30). Some have approached their environments with white gloves on, so to speak, seeking to learn and understand with limited personal investment and risk (i.e., an observational strategy; Papatsiba, 2006, p. 111). Still others have engaged the foreign environment head-on, actively seeking to both understand and invest in relationships with L2 speakers (i.e., an integrative strategy; Isabelli-García, 2006, p. 242). Naturally, these strategies can all be seen in one sojourner over time and are not static labels of how sojourners can act on affordances.

Research has also explored how sojourners’ personal characteristics and histories might relate to their use of one strategy or another. For example, a sojourner’s reasons for learning a language (e.g., academic, professional, linguistic, cultural, social) could make one strategy more obvious or sensible than others (Allen, 2010b). As already discussed, discourses in which sojourners have already participated (e.g., orientalism, globalization, educational strategies) can also frame their approach to study abroad even if they do not agree with them.

The strategies that sojourners draw upon may be persistent, but they are not static. On the contrary, sojourners draw on many different strategies depending on how their characteristics fit the situation in which they find themselves (Allen, 2013). Sojourners can also have conflicting desires within themselves that ebb and flow, manifesting in contradictory behaviors in a short period of time (Allen, 2010b; Quan, 2019; Wolcott, 2013). A sojourner might begin one day with a somewhat distanced, anthropological perspective, but become emotionally engaged in new relationships by the afternoon because of interactions with L2 speakers on a personally relevant topic. A sojourner might begin their study abroad with the intent to make close friends with L2 speakers, but retreat to compatriots and class work because they became uncomfortable with the perceived values of the foreign society. These changes in motivation and approach can happen within a day or across months. Participants may drift between approaches from week to week, or they may have month-long spurts of investment in one strategy broken up by a single experience.

The Negotiation of Difference

Deciding how to act or which strategy to follow involves a continuous process of negotiation, where the subject of negotiation is the meaning of action, and the intention of negotiation is for a sojourner’s actions to adequately express preferences and goals that are valid to sojourners and others in their environments (Tan & Kinginger, 2013). To make this possible, sojourners also negotiate differences among their own personal values, preferences, and emotions, especially as they see them in the unfamiliar light of a study abroad environment (Bae & Park, 2016; McGregor, 2014, 2016; Seo & Koro-Ljungberg, 2005). The research has identified several features of negotiation to describe how sojourners become familiar with new environments and start to act confidently and intuitively.

First, negotiation involves sojourners articulating their own preferences, values, desires, investments, expectations, and goals (Allen, 2010b; Bird, 2021; McGregor, 2014; Wolcott, 2013; Wolcott & Motyka, 2013; Yang & Kim, 2011). Research has most commonly seen this articulation when sojourners reflect on the tensions between their own preferences and those of others (Jackson, 2013; McGregor, 2014).

Second, negotiation involves sojourners experimenting with new ways of expressing themselves that may empower them to move forward toward their goals in the foreign environment. They do this by taking what they know about the foreign environment and trying to find common ground. They act within the foreign environment, observe the result, act again, and so on. This is apparent in short-term, repeated tasks (Kobayashi & Kobayashi, 2018), and in sojourners’ long-term efforts to learn a language (Bird, 2021).

Third and finally, researchers describe sojourners carving out a Third Space that makes sense of the home environment and the foreign environment (Kinginger, 2008; Smolcic, 2013). This can involve making creative arrangements in the foreign environment to satisfy sojourners’ goals and desires (Benson, 2012; Bird, 2021), and it can also mean that sojourners adjust or recreate their own identity to fit into existing arrangements (Jackson, 2011). The impetus, perhaps, for the sojourner inhabiting this place between places is the impossibility of expressing themselves in the foreign environment in the exact way as they had done in prior environments. As they are prevented from engaging in the foreign environment as they might have imagined, they are constrained to reimagine themselves with an identity that is compatible with the foreign environment (Barkhuizen, 2017). Finding this Third Place may reinforce sojourners’ deepest desires on which they are not willing to compromise, while also aligning with aspects of the foreign environment (Bird, 2021; Seo & Koro-Ljungberg, 2005; Trentman, 2013; Wolcott & Motyka, 2013, Yang & Kim, 2011). In Bird (2021), Chris struggled to square his introverted tendencies with an informal program expectation that he should be making friends with people in order to have better speaking experiences. Looking at the experiences of his American peers, it seemed that the best way to get good speaking practice was by becoming friends and doing a lot of hanging out, something with which he was not comfortable. Chris found, after some experimentation, that he could turn service interactions (i.e., with taxi drivers, shopkeepers, etc.) into engaging and challenging conversations. He was able to limit his social commitments and make progress toward his and the program’s linguistic goals.

It is not hard to imagine that Chris’s solution would be a poor fit for other sojourners or in a different context. A Third Space may be unique to the sojourner and difficult to imagine beforehand. The results of negotiation will vary for sojourners because those negotiations are mediated by the unique interaction of their personal characteristics and history with properties of the foreign environment (see Jin, 2012; Trentman, 2013). Sojourners differ in their possibilities to act because what looks like one and the same environment will present different affordances to each sojourner (Jackson, 2008).

Summary of Ecological Study Abroad Research

Ecological study abroad research reveals the complex interaction of sojourners with foreign environments, foregrounded by interaction with prior environments and mediated by perceived affordances and negotiations of difference. Regardless of whether sojourners retreat from or engage with the foreign environment, study abroad can act as a catalyst for change in sojourners’ future paths. Study abroad challenges sojourners to seriously consider and, for a period of time, live out the personal implications of learning a new language, and engage meaningfully with a foreign culture. What learners in their home countries might think of fondly as a kind of academic vacation or an on-ramp to global expertise can become an unexpectedly uncomfortable reconfiguration of sojourners’ identities in an unfamiliar foreign environment. Those who retreat when confronted with this reconfiguration settle for a lesser personal change (but not no change), while those who avail themselves of the unique affordances of a study abroad environment might experience deeper personal change. This change comes about as sojourners make sense of values from prior environments, the foreign environment, and within themselves.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR ECOLOGICAL STUDY ABROAD RESEARCH

Having summarized existing ecological research for language learning on study abroad, our insights can be compared to other fields. The field of closest interest is that of second language acquisition (SLA), on which many of the reviewed publications have drawn for conceptual support (Kramsch, 2003; Leather & Van Dam, 2003; van Lier, 2004). Reviews of SLA research from an ecological perspective have identified some relevant trends that are worth considering here. For example, Kramsch and Steffensen (2017) categorized ecological insights from SLA into different “views,” or lenses, that researchers used in their efforts to better understand learner experiences (see Figure 3). These include (a) an agent-environment systems view, (b) materiality-based and virtualitybased views, (c) identity-based views, and (d) value-based views. Here these views are briefly described, their contributions to the reviewed literature is discussed, and gaps are identified that can be filled through future research.

An Agent-Environment Systems View

Ecological SLA research has pushed back on the historical focus on the “language learner” as a bounded unit with mostly static characteristics and clearly defined paths for linguistic or cultural development. The research attempts to view people holistically, including their past history, their present relationships with the environment, and how these present possible ways to act going forward. Similarly, ecological study abroad research challenges static definitions of study abroad environments and participants, and describes the interaction of sojourner and environment in all their variety. Both SLA and study abroad research have drawn on ecological approaches (especially sociocultural ones) developed in other fields that consider the complexity and variety of experiences of learning a language. Research from this view provides detailed descriptions of sojourner experiences and highlights conflicts or affordances that would otherwise remain hidden. Overall, this view has encouraged the stakeholders of study abroad to consider sojourners on an individual basis rather than providing one-size-fits-all interventions.

Materiality-based and Virtuality-based Views

Some ecological research in SLA has begun investigations into the affordances of particular learning environments, such as online social interactions and augmented reality. They highlight Figure 3. Considering trends from ecological research in the field of second language acquisition. the constraints of different environments and the agent-environment systems that emerge when people use a second language within those environments. Augmented reality, virtual reality, and online social platforms merit ecological investigation as much as physical environments.

Given the recentness of SLA research into virtuality-based views, it may come as no surprise that ecological study abroad research has not yet provided many publications along these lines. Shively’s (2010) model for pragmatic instruction identifies possible affordances of digital tools at different points of a study abroad experience, but research so far has not taken on the task of deeply describing the material and virtual environments sojourners inhabit. Research along these lines might benefit sojourners by changing their relationship to technological resources while abroad. It may be that those who would use social media tools to virtually retreat from the foreign environment to more familiar relationships and interactions could learn to use those same tools to approach the foreign environment on safe ground. Virtual environments

might be repurposed as a tool to engage rather than distract.

Identity-based Views

Recent scholarship in SLA regarding identity was deeply affected by Norton (2013), who challenged the assumption that learner identities are made up of largely static characteristics that interact predictably with other factors. Ecological research in SLA has built on her work and describes learners with multiple identities that emerge from the interaction of micro-level events and macro-level ideologies and discourses (Diao & Trentman, 2016; McGregor, 2016; Shively, 2016).

Ecological study abroad research has made significant contributions to the study of identity along these lines. Sojourners and those supporting their sojourn anticipate that studying abroad will provide numerous, consistent, and intensive interactions. However, the research shows that they sometimes do not anticipate that these interactions will significantly challenge their identities. Study abroad research provides many case studies of sojourners that affirm the findings of general SLA research that identity is context-dependent and highly dynamic. The negotiation of difference (Block, 2007) has gained traction and been further developed for study abroad environments, where differences are consistently present that require sojourners to take action and potentially adjust their self-perceptions. Given the risks taken and the investments made by those studying abroad, it behooves the field to continue developing a firm understanding of the identity changes that sojourners might undergo while abroad.

Value-based Views

Finally, recent SLA research has started to explore how the value-laden nature of language weighs on learners as they struggle to balance different expectations and social norms. Within study abroad research many reports have touched on this balance by describing sojourners’ experiences with conflicting ideologies and norms (Bird 2021; Brown, 2014; Diao, 2017; Kinginger, 2004; Kinginger et al., 2014; Pellegrino, 1998; Seo & Koro-Ljundberg, 2005), but research in the field has primarily focused on identity as the unit of analysis (i.e., identity-based views) and has not clearly addressed the moral dimension of sojourners’ experiences (i.e., value-based views). Future research could deeply explore the tensions and balances that sojourners maintain while abroad, providing insights relating to the negotiation of difference and sojourner identity.

Next Steps

Existing ecological study abroad research has kept pace with SLA research in some areas but less so in others. It has made meaningful contributions regarding agency and the relationship between sojourner and environment, and many authors have contributed to developing a more holistic view of sojourner identity. On the other hand, research focusing on the affordances of material and virtual environments is largely absent, and research has rarely addressed values in more than a cursory manner. While further research is probably warranted in both of these areas, some immediate progress can be made regarding value-based views.

As already described, current publications hint at a complex world of values that sojourners must navigate (e.g., ideologies, cultural norms, personal values), but analysis of these issues so far is loosely connected and lacks a clear framework for making sense of what matters to sojourners and what they have to deal with. While this paper does not report findings from a value-based view, a critical task to be completed before conducting such research is defining what values are and how to properly investigate them in an ecological way. In other words, how can language researchers understand the morality of study abroad as a whole, not just for the narrowly defined “language learner,” but for everyone and everything in the environment in which study abroad for language learning occurs? Fortunately, other fields dealing with similar questions have created theories that conceptualize language and learning from a value-based, ecological perspective.

THE MORAL DIMENSION OF STUDY ABROAD

To facilitate research from a value-based perspective, this paper will briefly present common insights from two value-based accounts in different fields: Hodges’ (2015) values-realizing theory from ecolinguistics and Yanchar’s (2016) moral ecology of learning from psychology. The words “value,” “moral,” and other terms coined in these approaches (e.g., goods) do not draw on the notions of universal moral imperatives, classical ethics, or current economic, religious, or political connotations. Rather, they refer to the inherent meaningfulness of human experience and the concern involved in all human action. The following sections outline a conceptual framework by synthesizing principles presented in values-realizing theory and the

moral ecology of learning. The three primary claims are that (a) values are inherent in human practices, (b) participation in practice requires the balancing of values, and (c) balancing is a kind of moral stand-taking. For a more thorough discussion of hermeneutic moral realism, see Brinkman (2010) and Slife and Yanchar (2019).

Values are Inherent in Human Practices

A value-based approach to language learning holds that values exist in practices, as opposed to existing in people’s minds as psychological constructs or between people as social constructs (see MacIntyre, 1985). Humans participate in practices alongside others and using necessary equipment, and values make up the “boundary conditions” (Hodges, 2015, p. 715) that give practices form and enable interaction between a participant, other participants, and equipment. Two types of values can be identified that help define any practice.

First, there are “moral goods” (Yanchar & Slife, 2017, p. 4) that are the intrinsic ends or outcomes of participation in a practice—what the practice intrinsically yields up and, indeed, what functions as a major source of that practice’s purpose and meaning. For example, the practice of studying has the intrinsic good of learning, which could be described more specifically depending on the instance (e.g., memorizing vocabulary, refining a formal presentation, understanding grammar rules). To be clear, doing well on an exam, making friends in a study group, or finding employment are not intrinsic goods of studying, but rather are extrinsic, as they are not constitutive of the practice per se, but may occur as a kind of incidental byproduct. Moreover, they could be the goods of related practices and commonly realized alongside the goods of studying.

Second, there are “moral reference points” (Yanchar & Slife, 2017, p. 3) that guide participants in their pursuit of the intrinsic goods of a practice. Some reference points are constitutive of practices, and others might guide people to participate more effectively. For example, one cannot engage in studying without acting in relation to standards that define that practice. A constitutive reference point of studying could be honesty; to the extent that someone plagiarizes, they are not realizing the intrinsic good of studying. Non-constitutive reference points might include being well-rested and alert; these are criteria for excellent studying, but people can still study when they are tired, even if it is less effective.

These two types of values, the intrinsic moral goods and reference points that are inherent in practices, are “grounds for judgment that people encounter and must deal with in some way as they make sense of, and find direction in, the practical contexts of their lives” (Yanchar & Slife, 2017, p. 4). Without these values, practices would not exist, and people would have no bearings by which to make sense of practices and how to participate in them. Just as physical borders and landmarks demarcate countries and territories, values give shape and form to practices.

Participation in Practice Requires the Balancing of Values

A value-based approach to language learning recognizes that people commonly deal with multiple practices and values, normally without realizing or reflecting on it. Action requires not just dealing with one reference point at a time, but all reference points that are pertinent to the present practice(s) in which one is engaged. To use another physical comparison, walking through a forest entails moving in relation to not one, but many trees, and successfully navigating the forest requires orienting oneself to them. In the same way, a sojourner participating in a direct enrollment class at a foreign university might participate in group discussion, a practice with a unique landscape of moral reference points. Social reciprocity and time management might be relevant reference points that guide good group discussions, and as such, the sojourner might limit the number of comments he makes in order to respect the invested time of native-speaker students who are taking the class. The right balance of these reference points with others (e.g., speak in the target language often) would lead to realizing the moral goods of group discussion.

In familiar environments and practices, the task of balancing different values may often be smooth and not require participants to actively reflect on the values involved and how to balance them. Unfamiliar environments (or complications in an otherwise familiar environment) usually require some deliberate consideration of the values involved in a practice. For example, a sojourner may initially act at ease and could even be bored while purchasing groceries in a foreign language environment but resolving a minor complication could require unusual concentration from those involved, including an explicit consideration of the values involved in the practice of grocery shopping. For instance, if there were not enough change in the cash register, a sojourner might become consciously concerned with how to be a good customer by (a) paying a fair price, (b) acting politely to the cashier, (c) completing the transaction in a reasonable amount of time, and (d) doing all of these things within the limits of their language ability. The cashier, on the hand, might become consciously concerned with being a good cashier by (a) making a profit, (b) appeasing a customer, (c) completing the transaction in a reasonable amount of time, and (d) doing all of these things with someone who has limited language ability. Resolving the situation requires moving forward with a particular configuration of these values, with some of them taking more priority than others. Being a “good customer” or a “good cashier” in this situation requires more than linguistic expertise on the part of the sojourner and the cashier, but also familiarity with acceptable ways to balance these (and probably other) values in the moment.

This example highlights the balancing of values that might occur within a given practice, but similar balancing acts occur between practices whose goods and reference points may or may not fit together well. The customer in this example may waive the need for change, even if the price is unfair, because generosity is an important part of good citizenship, a separate practice with its own goods and reference points.

Balancing as a Kind of Moral Stand-Taking

A value-based approach also recognizes that actions constitute taking a kind of moral stand in a larger landscape of possible actions; “they are one’s judgments, whether tacit or deliberate, regarding practices worth pursuing” (Yanchar, 2016, p. 507). This is especially evident in language use:

When humans speak and listen, or write and read [...] these actions irreversibly place us. [...] To postulate a question, a statement, or even to give a grunt or a groan is to locate oneself, to take a stance with respect to oneself, to others [...] and to the geographies and tasks within which those selves are located. Actions, including those of ordinary conversations [...] cannot be done without pointing to oneself and to the responsibility entailed in speaking or listening. (Hodges & Fowler, 2010, p. 240)

Sojourners constantly situate themselves in relation to the actions of other sojourners, the programs they participate in, and the people who inhabit both prior and foreign environments. At one level, sojourners already distinguish themselves from many other language learners by engaging in the practice of study abroad. Traveling to and living in a foreign environment requires turning down other opportunities (educational or otherwise), which is a statement about the value of study abroad for sojourners and the kind of person they value becoming. At a more detailed level, sojourners within a specific study abroad experience may align with the program and other participants in some ways, and not in others. A study abroad program might provide general direction regarding how sojourners should go about best achieving the intrinsic goods of study abroad (whatever those goods are), but each sojourner will take a unique moral stand by virtue of how they manage or balance relevant values to best achieve the good of practice in a given context.

Participating in a practice and how well one performs in it is loaded with value in a larger world of practices and within a person’s life story; they say something about what is worth doing. Situating oneself in a larger moral ecology can be complicated or controversial, but it is also inescapable and potentially beneficial. “We need to disagree and agree with others in a way that moves us to enrich the physical, social, and moral possibilities of our environment” (Hodges, 2015, p. 731).

IMPLICATIONS FOR STUDY ABROAD RESEARCH

The previous section outlines what a moral ecology is made of: practices, goods, reference points, and the stances that sojourners take as they balance competing values. The final questions regarding a value-based approach to study abroad are: how does one go about conducting research from this perspective, and what could this research contribute to the field?

Researching Study Abroad from a Value-based View

To look at study abroad from a value-based perspective is to see the moral landscape that sojourners inhabit. Different research frameworks could conceivably take on this perspective and reveal the moral ecology of study abroad in insightful ways. Yanchar and Slife (2017) proposed one such framework for exploring the fit of a phenomenon (e.g., attending a direct enrollment course) in the moral space of a practice (e.g., studying abroad). In this framework they outline four general questions related to (1) the moral significance of practices, (2) the moral demands of practice, (3) the role of practices in becoming, and (4) the moral complexities that emerge within and between practices (for examples, see Gong & Yanchar, 2019; McDonald & Michela, 2019; Yanchar & Gong, 2019; Yanchar & Gong, 2020).

Moral Significance

First, what significance does a phenomenon have related to the intrinsic goods of a practice? For example, how does participating in a direct enrollment course enable or hinder realizing the goods of study abroad? Research might reveal that the course was a good fit for sojourners with a particular orientation to the goods of study abroad, whereas others experienced it as a hindrance or distraction. For the former, the course might have enabled a certain kind of study abroad experience that emphasizes certain goods (e.g., developing cross cultural relationships). For sojourners who took a different moral stand by prioritizing the goods of study abroad in other ways, the course might have been a less effective use of time spent abroad. Research could compare the direct enrollment course to other activities and discuss how they facilitated or hampered sojourner efforts to excel in the practice of study abroad.

Moral Demands

Second, what does the phenomenon reveal about the moral reference points involved in practices? For example, what evaluations do sojourners make about the different ways that people can go about realizing moral goods? Research could investigate which reference points exerted moral demands on sojourners as part of their participation in a direct-enrollment course, such as respect for authority or social reciprocity. Being a sojourner in this context may have involved tacitly prioritizing these reference points among many others. Sojourners may have acted in ways that valued efficient time use more than social reciprocity and respect for authority by speaking more than other students during discussions, ignoring or interrupting the instructor, and complaining about assignments to be completed on their own time. The way that they went about participating constituted a moral stand in relation to moral demands outside themselves.

However, sojourners’ orientations to moral demands can change over time, perhaps by finding a better way to achieve the goods of practice. For example, sojourners could find that completing course assignments before they attend class enables them to participate more fully in class activities and thereby improve their linguistic ability. Yet another reason to change could be that sojourners reoriented themselves to the goods that they pursued. In other words, sojourners may have changed what they think is worthwhile about study abroad generally, which could have changed how the course fit into their experience.

Moral Becoming

Third, what role does the phenomenon play in sojourners becoming a more skillful participant in practice? To offer another example, how does participating in study abroad fit into people’s efforts to become more adept language users? Research could produce a moral narrative describing how their orientation to the goods and reference points involved in language learning shifted over the period of their sojourn. Understanding sojourners’ past experiences, their current efforts, and their future possibilities could frame a story of striving for excellence, with some degree of success, in the moral ecology of their study abroad program.

Moral Complexities

Fourth, what moral complexities do people struggle with in the midst of practice? How do they balance competing moral reference points, or possibly competing moral goods of different practices? If developing cross-cultural relationships is an intrinsic good of study abroad, but if sojourners find that developing meaningful relationships requires more emotional energy than they are capable of giving on a given day, how do they balance taking care of themselves with their social investments so that they can optimally realize the goods of study abroad? On the one hand, they may find ways to optimize their emotional capacity (e.g., a planned routine with dedicated personal time) and patiently keep looking for new

contacts that require less emotional involvement than others they have met. On the other hand, they may retreat to a degree from social life at the expense of becoming close friends with native speakers, while other intrinsic goods of study abroad (e.g., linguistic competence) take greater precedence.

Potential Contributions of Value-based Research

The theoretical foundation and the framework discussed above provide ways of conceptualizing study abroad so that researchers can observe, analyze, and share findings from a perspective that is fundamentally concerned with what matters to sojourners as they participate in practices. Three apparent benefits stand out that this approach might offer to researchers, practitioners, and sojourners. Theoretically, this perspective enriches the ecological concept of the negotiation of differences. From a more practical standpoint, it contributes to the designing of relevant study abroad programs and helps apply insights to specific circumstances.

The Negotiation of Difference

The negotiation of difference is a pivotal concept of ecological research that brings together many other concepts (e.g., macro-level discourses, affordances, Third Space) in ways that reflect the researcher’s phenomenon of interest. The types of differences that have emerged in previous publications reflect the approach of the researchers. For example, research taking an identity-based approach might discover tensions caused by a difference between sojourner personal characteristics (e.g., nationality, gender) and cultural norms in the foreign environment. Not only does this value-based approach give researchers a lens for seeing other types of differences (i.e., moral complexities), but it also adds more theoretical detail to the process of negotiation itself. Our earlier review of the process presented three parts: (1) articulating preferences, values, desires, etc., (2) finding common ground, and (3) creating a Third Space.

First, this value-based approach theorizes practices as the context in which preferences and desires (i.e., values) can be naturally articulated, and these values can be described either as practical goods that sojourners pursue, or as reference points that they consider in order to realize those goods. This description of value types and the way they are expressed in practice can provide useful mental scaffolding for sojourners as they reflect on their experiences and compare their own values with different ones in a foreign environment.

Second, finding common ground occurs as sojourners become more familiar with the values inherent in practices performed in a foreign environment. They feel out the contours of a practice (e.g., lecture-style instruction) until they understand its purpose (e.g., knowledge transmission) and common guides for achieving its purpose (e.g., memorization). Becoming somewhat familiar with a variety of practices and their embedded goods and reference points would enable sojourners to see similar practices and values in their own histories. Practices that align best with the kind of person they are striving to become would prove ideal for finding common ground.

Third, inhabiting a Third Space can be described as becoming, a kind of stance-taking regarding what is worth doing. The metaphor of a Third Space can be enriched by the spatial metaphor of a moral ecology, where sojourners position themselves in relation to other individuals and societal groups by settling on a particular way of studying abroad. Inhabiting a Third Place is a commentary on what study abroad is good for, and the process of negotiation that sojourners undergo in order to create their own Third Place is a commentary on how best to go about studying abroad.

A New Metaphor to Guide Practitioners

If practitioners intend to enhance study abroad for the benefit of sojourners, then they must know the sojourners better. Prior research has conceptualized (i.e., known) sojourners using metaphors that approximate human experience, which directly affect the kind of support practitioners provide. A computer-processing metaphor, for example, may draw attention to sojourners’ mental processes and limitations, and may lead to interventions intended to reduce cognitive load or maximize knowledge retention. Many such metaphors have produced significant insights for improving sojourners’ experiences and considering more than one can be beneficial (Sfard, 1998).

This value-based approach assumes a very different metaphor than those commonly seen in study abroad literature. Perhaps most centrally, it describes human beings as agents embodied in a world of meaning. It provides a detailed way of understanding human experience without proposing causal mechanisms that control human experience. Yanchar and Slife (2017) propose that “knowing who a person is, from this perspective, is to know his or her moral stance and moral becoming as a kind of commentary on moral goods” (p. 17). In other words, exploring the moral landscape that sojourners inhabit, and knowing where they stand in it, is important to designing and evaluating study abroad experiences. While experienced practitioners may already have a sense of these things, research could make their tacit understandings more explicit (to some degree) and easier to apply.

Bridging the Theory-Application Gap

Applying the findings of research to a specific program or sojourner is rarely straightforward. Published standards and best practices are intended to guide policies and interventions, but do not often consider the complexities of real life. For example, sojourners who participate in content courses in the target language during study abroad tend to improve their oral proficiency more than those who do not (Vande Berg, et al., 2009). However, a sojourner participating in a content course may feel that recommended preparation for class discussions takes time away from other worthwhile activities, such as hanging out with native-speaker friends. How should the sojourner proceed? Should the course be given absolute priority? Probably not in all cases, but what does an acceptable balancing of priorities look like? This is one question that value-based approaches are well equipped to answer, since moral complexities describe exactly this phenomenon.

A previous example discussed the moral goods and reference points that might become salient when a cashier runs out of change to give to a sojourner customer. However trivial or mundane this may seem, a thorough investigation of what it means to be a “good customer” or “good cashier” in this situation could reveal moral configurations that future sojourners may encounter. For Yanchar and Slife (2017), the value of these insights is two-fold:

[A] researcher’s moral explication of such situations might not only reveal these moral tensions, thus providing clarification about what is actually happening [...] but also show how others have navigated the balancing process, thus providing a practical bridge between abstract and everyday ethics. (p. 18)

Sojourners, especially those going abroad for the first time, are immersed not only in a different world linguistically and culturally, but also practically and morally in the sense we have described. Their developments occur in light of intrinsic moral goods and reference points that they have to deal with in one way or another. Just as sojourners receive linguistic and cultural training before study abroad to prepare them for the linguistic and cultural ecologies they will encounter, seeing how others have effectively (or ineffectively) prioritized values in a similar study abroad environment could help sojourners to more rapidly familiarize themselves with, position themselves in, and enrich their possibilities within a new moral landscape.

CONCLUSION

This paper outlines ecological research of study abroad for language learning, identifies valuebased views as a guide for further inquiry, and proposes a framework for describing the moral ecology that sojourners inhabit. The ecological perspective of study abroad is distinguished by its focus on complex relationships that exist between sojourners and their environments (i.e., affordances), its consideration of sojourners as whole people with histories and changing identities, and its interest in how sojourners negotiate differences between their own values and those of the foreign environment. Understanding how sojourners orient themselves to the values of their study abroad environments is critical to knowing how to support them as they engage with unfamiliar cultural norms and discourses, and a moral ecology framework provides a theoretically powerful but practically simple way for researchers and practitioners to improve study abroad programming.

REFERENCES

Allen, H. (2010a). Interactive contact as linguistic affordance during short-term study abroad: Myth or reality? Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 19, 1-26.

Allen, H. W. (2010b). What shapes short-term study abroad experiences? A comparative case study of students’ motives and goals. Journal of Studies in International Education, 14(5), 452-470.

Allen, H. W. (2010c). Language‐learning motivation during short‐term study abroad: An activity theory perspective. Foreign Language Annals, 43(1), 27-49.

Allen, H. W. (2013). Self-regulatory strategies of foreign language learners: From the classroom to study abroad and beyond.In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Socialand cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad(pp. 47-73). John Benjamins Publishing.

Bae, S., & Park, J. S. Y. (2016). Becoming global elites through transnational language learning: The case of Korean early study abroad in Singapore. L2 Journal, 8(2), 92-109.

Barkhuizen, G. (2017). Investigating multilingual identity in study abroad contexts: A short story analysis approach. System, 71, 102-112.

Benson, P. (2012). Individual difference and context in study abroad. In W. M. Chan, K. N. Chin, S. Bhatt, & I. Walker (Eds.), Perspectives on individual characteristics and foreign language education(pp. 221-238). De Gruyter Mouton.

Benson, P., Barkhuizen, G., Bodycott, P., & Brown, J. (2012). Study abroad and the development of second language identities. Applied Linguistics Review, 3(1), 173-193.

Bird, M. (2021). Struggling to engage with Arabs on study abroad: Negotiating expectations for speaking [Manuscript submitted for publication].

Block, D. (2007). The rise of identity in SLA research, post Firth and Wagner (1997).The Modern Language Journal,91(1), 863-876.

Brown, L. (2014). An activity-theoretic study of agency and identity in the study abroad experiences of a lesbian nontraditional learner of Korean. Applied Linguistics, 37(6), 808-827.

Coleman, J. A. (2013). Researching whole people and whole lives. In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad (pp. 17-44). John Benjamins Publishing.

Diao, W. (2017). Between the standard and non-standard: Accent and identity among transnational Mandarin speakers studying abroad in China. System, 71, 87-101.

Diao, W., & Trentman, E. (2016). Politicizing study abroad: Learning Arabic in Egypt and Mandarin in China. L2 Journal, 8(2), 31-50.

Gong, S. P., &Yanchar, S. C. (2019). Question asking and the common good: A hermeneutic investigation of student questioning in moral configurations of classroom practice.Qualitative Research in Education,8(3), 248-275.

Hodges, B. H. (2015). Language as a values-realizing activity: Caring, acting, and perceiving. Zygon, 50(3),711-735.

Hodges, B. H., & Fowler, C. A. (2010). New affordances for language: Distributed, dynamical, and dialogical resources.Ecological Psychology,22(4), 239-253.

Isabelli-García, C. (2006). Study abroad social networks, motivation and attitudes: Implications for second language acquisition.In M. Dufon & E. E. Churchill (Eds.), Language learners in study abroad contexts(pp. 231-258).Multilingual Matters.

Jackson, J. (2008). Language, identity and study abroad: sociocultural perspectives. Equinox Publishing.

Jackson, J. (2011). Mutuality, engagement, and agency: Negotiating identity on stays abroad. In C. Higgins (Ed.), Identity formation in globalizing contexts: Language learning in the new millennium(pp. 127-145). De Gruyter Mouton.

Jackson, J. (2013). The transformation of ‘a frog in the well’: A path to a more intercultural, global mindset.In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad(pp. 179-204). John Benjamins Publishing.

Jang, I. C. (2015). Language learning as a struggle for distinction in today’s corporate recruitment culture: An ethnographic study of English study abroad practices among South Korean undergraduates. L2 Journal, 7(3), 57-77.

Jin, L. (2012). When in China, do as the Chinese do? Learning compliment responding in a study abroad program.Chinese as a Second Language Research,1(2), 211-240.

Kinginger, C. (2004). Alice doesn’t live here anymore: Foreign language learning and identity reconstruction. Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts, 21(2), 219-242.

Kinginger, C. (2008). Language learning in study abroad: Case studies of Americans in France. The Modern Language Journal, 92(1), 1-124.

Kinginger, C. (2010). American students abroad: Negotiation of difference? Language Teaching, 43(2), 216-227

Kinginger, C. (2015). Language socialization in the homestay: American high school students in China.In R. Mitchell, N. Tracy-Bentura, & K. McManus (Eds.), Social interaction, identity and language learning during residence abroad(pp. 53-74). European Second Language Association.

Kinginger, C. (2017). Language socialization in study abroad. In P.A.Duff & S. May (Eds.), Language socialization. Encyclopedia of language and education (3rded.). Springer.

Kinginger, C., & Belz, J. A. (2005). Socio-cultural perspectives on pragmatic development in foreign language learning: Microgenetic case studies from telecollaboration and residence abroad. Intercultural Pragmatics, 2(4), 369-421.

Kinginger, C., Lee, S. H., Wu, Q., & Tan, D. (2014). Contextualized language practices as sites for learning: Mealtime talk in short-term Chinese homestays. Applied Linguistics, 37(5), 716-740.

Kobayashi, M. (2016). L2 academic discourse socialization through oral presentations: An undergraduate student’s learning trajectory in study abroad. Canadian Modern Language Review, 72(1), 95-121.

Kobayashi, E., & Kobayashi, M. (2018). Second language learning through repeated engagement in a poster presentation task. In M. Bygate (Ed.), Learning language through task repetition(pp. 223-254). John Benjamins Publishing.

Kramsch, C. (Ed.). (2003).Language acquisition and language socialization: Ecological perspectives. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Kramsch, C., & Steffensen, S. V. (2008). Ecological perspectives on second language acquisition and socialization.Encyclopedia of language and education,8, 17-28.

Leather, J.,& van Dam, J. (Eds.). (2003). Ecology of language acquisition. Kluwer.

Liu, C. (2013). From language learners to language users: Astudy of Chinese students in the UK. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 23(2), 123-143.

MacIntyre, A. (1985).After virtue(2nd ed. with postscript). Duckworth. (Original work published 1981)

McDonald, J. K., & Michela, E. (2019). The design critique and the moral goods of studio pedagogy.Design Studies, 62, 1-35.

McGregor, J. (2014). “Your mind says one thingbut your emotions do another”: Language, emotion, and developing transculturality in study abroad. Die Unterrichtspraxis/Teaching German, 47(2), 109-120.McGregor, J. (2016). “I thought that when I was in Germany, I would speak just German”: Language learning and desire in twenty-first century study abroad. L2 Journal,8(2), 12-30.

McKeown, J. S. (2009). The first time effect: The impact of study abroad on college student intellectual development. SUNY Press.

Norton, B. (2013).Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Multilingual matters.

Papatsiba, V. (2006). Study abroad and experiences of cultural distance and proximity: French Erasmus students. Languages for Intercultural Communication and Education, 12, 108.

Patron, M. C. (2007). Culture and identity in study abroad contexts: After Australia, French without France(Vol. 4). Peter Lang.

Pellegrino, V. A. (1998). Student perspectives on language learning in a study abroad context. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad, 4(2), 91-120.

Pipitone, J. M., & Raghavan, C. (2017). Socio-spatial analysis of study abroad students’ experiences in/of place in Morocco. Journal of Experiential Education, 40(3), 264-278.

Quan, T. (2019). Competing identities, shifting investments, and L2 speaking during study abroad. L2 Journal, 11(1), 1-19.

Seo, S., & Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2005). A hermeneutical study of older Korean graduate students’ experiences in American higher education: From Confucianism to western educational values. Journal of Studies in International Education, 9(2), 164-187.

Sfard, A. (1998). On two metaphors for learning and the dangers of choosing just one.Educational Researcher,27(2), 4-13.

Shardakova, M. (2013). “I joke you don’t”: Second language humor and intercultural identity construction. In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Socialand cultural aspects of cross-border language learning in study abroad(pp. 207-238). John Benjamins Publishing.

Shively, R. L. (2010). From the virtual world to the real world: A model of pragmatics instruction for study abroad. Foreign Language Annals, 43(1), 105-137.

Shively, R. L. (2016). An activity theoretical approach to social interaction during study abroad.L2Journal, 8(2), 51-75.

Shively, R. L. (2018). Learning and using conversational humor in a second language during study abroad(Vol. 2). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Siegal, M. (1995). Individual differences and study abroad: Women learning Japanese in Japan. In B. Freed (Ed.), Second language acquisition in a study abroad context(pp. 225-244). John Benjamins.

Slife, B. D., &Yanchar, S. C. (Eds.). (2019).Hermeneutic moral realism in psychology: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Smolcic, E. (2013). Opening up to the world. Developing interculturality in an international field experience for ESL teachers. In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad(pp. 75-100). John Benjamins Publishing.

Steffensen, S.V., & Kramsch, C. (2017). The ecology of second language acquisition and socialization. In P. Duff & S. May (Eds.), Language socialization. Encyclopedia of language and education(3rded., pp. 1-16). Springer.

Tan, D., & Kinginger, C. (2013). Exploring the potential of high school homestays as a context for local engagement and negotiation of difference. In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad(pp. 155-177). John Benjamins Publishing.

Trentman, E. (2013). Imagined communities and language learning during study abroad: Arabic learners in Egypt. Foreign Language Annals, 46(4), 545-564.

Umino, T., & Benson, P. (2016). Communities of practice in study abroad: A four‐year study of an Indonesian student's experience in Japan. The Modern Language Journal, 100(4), 757-774.

Vande Berg, M., Connor-Linton, J., & Paige, R. M. (2009). The Georgetown consortium project: Interventions for student learning abroad.Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad,18(1), 1-75.

van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Kluwer.

Wilkinson, S. (1998). Study abroad from the participant’s perspective: A challenge to common beliefs.Foreign Language Annals,31(1), 23-39.

Wolcott, T. (2013). Myth, desire, and subjectivity in one student’s account of study abroad in France. In C. Kinginger (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad(pp. 127-154). John Benjamins Publishing.

Wolcott, T., & Motyka, M. J. (2013). Subjectivity and spirituality during study abroad: A case study. L2 Journal,5(2), 22-42.

Yanchar, S. C. (2016). Identity, interpretation, and the moral ecology of learning.Theory & Psychology,26(4), 496-515.

Yanchar, S. C., & Gong, S. P. (2019). Inquiry into moral configurations.In B. D. Slife & S.C. Yanchar(Eds.),Hermeneutic moral realism in psychology: Theory and practice(pp.116-127).Taylor & Francis Group.

Yanchar, S. C., & Gong, S. P. (2020). Moralcomplexities ofstudentquestion-asking inclassroompractice.Phenomenology & Practice,15(2), 73-99.

Yanchar, S. C., & Slife, B. D. (2017). Theorizing inquiry in the moral space of practice.Qualitative Research in Psychology,14(2), 146-170.

Yang, J. S., & Kim, T. Y. (2011). Sociocultural analysis of second language learner beliefs: A qualitative case study of two study-abroad ESL learners. System, 39(3), 325-334.