The future is unpredictable, and we need to prepare our students to be ready for it. To navigate such uncertainty, higher education institutions need to provide students with the knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values needed for success in life. These new challenges require higher education institutions to evaluate their teaching and learning practices and develop new ways to inspire, empower, and transform students' learning experiences – which requires enabling students to exercise agency over their learning choices. Teachers can support agency by recognizing students’ individuality, abilities, and interests. Together, teachers and students can co-create personalized learning plans that will motivate and empower students to develop the skills they need to nurture their passions and pursue their goals.

Introduction

Universities need to develop curricula with their students’ needs in mind and prepare them with skills they need that will allow them to thrive and continually adapt in a complex and rapidly changing world. This skill set consists of noncognitive, cognitive, and job-specific skills. Noncognitive skills such as teamwork, perseverance, motivation, critical thinking, creativity, communication, problem-solving and collaboration are critical to students’ success in the classroom and the workplace (Brunello & Schlotter, 2010; Levin, 2012; World Economic Forum, 2016; Ehlers & Kellerman, 2019). Other characteristics needed for managing challenges of the 21st century also include mindsets (Dweck, 2008), and personal qualities (Duckworth & Yeager, 2015). Students are not empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, but rather, whole persons with dreams and aspirations and connections to their world. Educators have the unique opportunity to create transformative learning environments in which students are at the centre of the learning process.

In this chapter, I share personal teaching practices and reflections on how I use heutagogical principles to unleash the power of learner agency and prepare students to thrive in an unpredictable world. I will also share student reflections on the importance of self-determined learning.

Principles of teaching and learning

The principles I use are based on the notion of transformational learning, which is defined as a process of questioning old assumptions, values, perspectives, and beliefs and making them more open and accessible (Mezirow, 2000). Knowing our students and their world is the first step to designing a transformative learning experience for all.

The following teaching and learning principles allow me to empower students to believe in their ability to achieve their highest potential. In this section, I will describe why each principle is critical to developing learner agency:

- Knowing your students

- Knowing how your students learn

- Respecting diverse backgrounds, talents, and ways of learning

- Aligning learning objectives, assessments, and instructional activities

- Communicating student-driven expectations and objectives

- Offering formative feedback

- Ongoing learning and reflection

Knowing your students

Knowing my students involves developing a student profile to identify their motivations, aspirations, and challenges. I gather information from enrolment data and from the students themselves about age, marital status, socioeconomic background, race, and ethnicity, and native versus international. A week or so before the first class, I send out an email or a video to students with information about the course, my background, my teaching methods, skills they’ll learn, how the course relates to their life, and how enthusiastic and passionate I am about teaching and working with them. At this time, I also introduce the concept of “first impressions” and the belief that we only have about seven seconds to make a first impression (Dovico, 2016; Robles, 2012).

I then begin developing my course with the student in mind. Various sections of the course are designed together with my students during our first class. By doing this, I develop trust, respect, and interest in all of my students, which motivates them to commit to their learning goals and is important to success (Cornelius-White, 2007; Koca, 2016).

A first-class icebreaker allows students to introduce themselves to others and practice the first impression experience in real time. Then we discuss how the perception of others aligns with their perception of themselves. At this time, we also discuss the importance of communication, values, cultures, and perceptions. This principle is useful in developing learner agency as students become motivated and committed to their learning because it’s relevant to their own needs and goals.

Know how students learn

Metacognition is the process of thinking about one’s own thinking or awareness and management of one’s own thoughts (Flavell,1979; Kuhn & Dean, 2004). One way in which students achieve metacognitive awareness is by practicing mindfulness meditation, which has been defined as the awareness that emerges from paying attention on purpose in a non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). I also use mindfulness to help students become aware of their strengths and weaknesses, reflect on their thinking, and control their stress and anxiety.

People are born learners and have a need for agency, autonomy, and self-determination (Hase, 2016; Spence, 2001). However, understanding how one learns and thinks about one’s own learning can help in becoming a more accomplished learner. In particular, metacognition can assist in recognising barriers to learning and pave the way to removing them. Teacher-centric learning that relies more on pedagogy can take agency and be a barrier to learning (Brandt, 2013) whereas more learner-centred approaches enable agency (see Chapter 1).

Respecting diverse backgrounds, talents and ways of learning

Students bring to the classroom varied cultural backgrounds, knowledge, skills, and attitudes that impact how they learn, their self-efficacy for learning, and their learner agency. I try to design my learning processes to accommodate all types of learners from all backgrounds. One heutagogical approach that I use is that students select learning activities that fit the way they learn best. Thus, the learner is an active partner and has agency in determining the learning process with the teacher as a guide in recognition of individuality. In addition, we want to ensure that together we create a safe learning environment where everyone thrives by being aware of our individual differences (Velliaris, 2016).

Aligning learning objectives, assessments, and instructional activities

Providing students with experiential and authentic learning activities allows students to become motivated to discover and construct knowledge and to develop a greater appreciation for the subject matter and longer content retention. Role playing and service learning are two authentic activities that students enjoy as they interact with other students and apply their own knowledge to real world situations (Coker, Heiser, Taylor, & Book, 2017; Ma, 2020).

Communicating expectations and objectives

Teachers and students alike have personal expectations (Bacerra, 2012; Rubie-Davies, 2012). Awareness and sharing of these expectations are important in the learning partnership. This is especially true for my international students and first-generation students whose educational experiences may be different to mine and each other’s.

Offering diverse methods of feedback

Feedback is important to learning and growth (Voinea, 2018). Formative feedback helps promote learner agency. It enables students to be in control of and to reflect on their learning, change behaviour where needed, and to develop persistence and resilience to finishing the work: skills they need to thrive in the real world. Feedback as assessment can be used as part of the learning process rather than an end in itself, with the learner as a partner (Hase and Kenyon, 2000; Hase, 2011).

Ongoing learning and reflection

Reflective practice is intended to promote critical thinking. Students reflect on their learning and how it applies to the real world. By doing so, students become empowered to self-correct habits of mind as they may become evident during the reflection process. Reflective learning is equally important to teachers. As a reflective educator practitioner, I use evidence to continually evaluate and adapt to meet the needs of each student and of my own.

Strategies

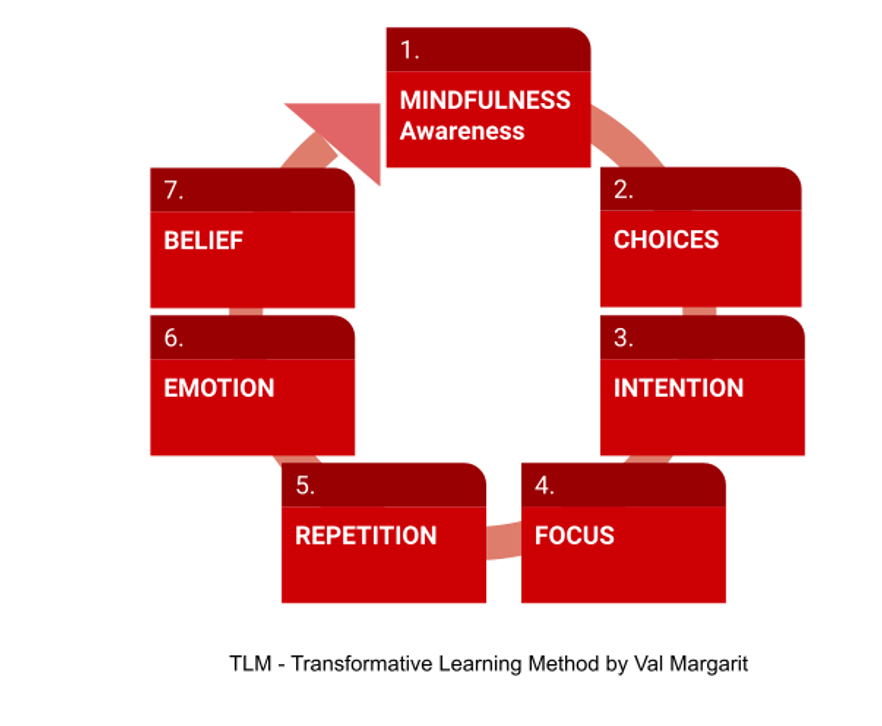

Next, I will share seven strategies I use to help my students become the designers of their own learning journeys. These strategies are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Seven Strategies

Step 1: Mindfulness

Students participating in mindfulness practice show a significant improvement in cognitive skills, social skills, and noncognitive skills (Bostic et al, 2015; Klingbeil et al, 2017; Campbell, 2013). Moreover, mindfulness helps with awareness, stress and anxiety decrease, and enhances resilience and self-control. Self-control empowers students to regulate their emotional, cognitive flexibility and to increase attention and focus on learning and completing a task (Eberth & Sedlmeier, 2012; Goyal Singh, et al, 2014).

Class application. Introducing the concept of mindfulness, I share my personal experience with it and include a video explaining its benefits. In groups, students research the topic further and present the findings to class. Each class begins with a few minutes of mindfulness meditation, then we set an intention for class, and then finish the class with self-reflection journaling. These principles are supported by various theories including heutagogy, self-determined, and humanistic theories (Hase & Kenyon, 2000; Blaschke, 2012) Moreover, journaling about learning experience helps in growth development, critical thinking, focus, and clarity. Through the assignment, students have felt a sense of empowerment and control over their lives.

Student C reflected:

I had an amazing experience in this class, it encouraged me to meditate every day. Especially during this pandemic, I started doing spiritual meditation which helped release and settle my thoughts and emotions, relaxes my nervous system, and helps my body unwind from stress also helped to let go of the past and sink in peace which helped me realize who you really are.

Step 2. Choice

Students become engaged in their learning if they perceive that they have choices, which creates a sense of autonomy, and competence. Students learn about conscious choices that are directly related to their own interests, which increases student success (Blaschke and Hase, 2015). It is always my goal to empower all students to take action and to be in charge of their learning, of making conscious choices, and reflecting on their progress, adjusting and adapting.

Class application. Create a vision for the course with your students. Have a conversation about learning outcomes, why they are important, and how to achieve them. Ask students about the skills they need to thrive in the real world and then point out how the course assignment choices will help them learn and practice those skills. My philosophy is, if it’s not applicable and useful in the real world then it’s not worth teaching it'. Giving choices and autonomy over their learning seems to help students unleash their learner agency.

Step 3: Intention

Choice is empowering and requires students to be intentional. I take a co-leader or facilitator role in this learning journey, ready to support, explain, guide, motivate, empower, and inspire students to stay focused on their goals and develop the skills necessary to achieve them (Hase, 2017). Self-control over learning enables learner agency.

Class application. I work with students to identify what we need to learn, why, how, and what methods of assessment we should use. Each class starts with identifying objectives for the session. Students are aware, engaged, motivated, responsible and accountable in this process because they realize it is about them and their future, and their success is relative to the effort they put in. The primary questions are: what are we going to learn today, how, and why?

Step 4: Focus

Mindfulness concerns being present and observing one’s own thoughts. Focus involves paying attention and training the mind to focus on an intention or goal and to ignore distractions. So, training the mind to focus is one of the most important skills students need to achieve success in school and at work. I often ask students “who will you be at the end of the class?” Students learn about the setting, planning, measuring and completing goals. As student R said:

Four weeks ago, I was sluggish and unmotivated. Now I feel empowered and have a more peaceful mind because I've taken the time to focus on controlling what I can control and not feeling that I have to change or fix everything. I am most proud of relaxing my mind. I had a lot of anxiety and chose to ignore it and it only got worse. I am proud to say that I don't have anxiety as I did before. The skills I learned in this class with Professor Val will help me be successful in life: Meditating, Confidence, Positive thinking, Resilience, Focus. Professor Val has taught me how to control and train the mind to focus on goals I want to accomplish and not worry about things I cannot control. I feel empowered. It’s a great feeling.

Class application. We begin by having a conversation about why it’s important to train the mind and the brain to focus on what we want to achieve. I use the example of smart phones, addiction to smartphones is related to psychological and physiological health issues (De-Sola Gutiérrez, Rodríguez de Fonseca, and Rubio, 2016; Boumosleh & Jaalouk, 2017). We discuss stress, anxiety, depression, and inability to control emotions, all because of the inability to stay away from the phone and focus on the goal at hand. We agreed to collect all of our phones at the beginning of class and to take a tech break every 30 minutes for 5 minutes. I teach my students to focus all their attention on breathing and to count to ten. Every time the mind wanders (check email, check phone, where is my key?), they have to start over again until they are able to count to ten. I share several focus and productivity apps such as Stay Focused, a productivity extension for Google Chrome that helps us stay 'focused' on our work; TimeStats and RescueTime shows where we’ve been online and how we spend our time.

Step 5. Repetition

Do you remember a moment when you scored a perfect 10 on a test, learned to drive, or passed a difficult exam? Our performance improves when we practice over and over especially at various intervals of time (Kang, 2016). Repetition is of vital importance to the learning process. It is through repetition that we make the unfamiliar familiar. For instance, reading books on how to drive a car, or public speaking, time management, diets, mathematics, running, or any other academic or physical skills will not teach students how to do any of these skills successfully unless they take action and begin to practice them. It is through repetition that they learn and improve performing any skills. As the old adage reminds us, 'practice makes it perfect.'

Class application. I tell students that the secret to successful learning is repetition and perseverance. To learn a new skill or habit, we need to repeat the behaviour until it becomes natural. This is achieved by using different learning methods to cover the same skill such as discovery learning, flipped classroom technique, and experiential learning and assessment. Here are several ways I use repetition to make sure students remember what they’ve learned and continue to practice the skills and attitudes they need in the real world:

- At the beginning of class, we recall what we covered in the previous class. Each student shares at least three 'aha moments' or 'takeaway points.'

- At the end of each class, students write in their reflection journals about how they spent their time, what they learned, and how it’s connected to their learning objectives, academic goals, and life in general.

- Every Friday, we have a chapter review. In groups, students discuss their weekly learning and growth. Then one student per group shares her or his combined learning.

- Students have a weekly guided journal assignment that asks to answer open-ended questions about their learning experience, suggestions for improvement, and what as a class we should do differently the following week in order to improve and thrive.

- Throughout the semester, students are asked to recall what skills they have been cultivating and how they assess their performance. These skills are first discussed at the beginning of the course to increase awareness of the skills they need in school, work, and life.

As student J reflected:

I feel empowered and educated because being able to talk about how socialization is important in our society makes me learn more about human behaviour and in the future became a much better global citizen. For example, it's important to socialize people from a young age to learn skills like respect, teamwork, and being able to communicate with others. It is through practice and repetition that I was able to polish these skills, which would help me achieve success in life.

Step 6: Emotion

Students will commit to projects that are meaningful and are related to their own lives. Creating positive emotion by design may seem difficult at first. However, with practice, it will become easier, and they learn to control how they feel. For example, many students lack self-confidence, self-esteem, and time management skills, all of which they need to survive and thrive in the real world. Practicing mindfulness teaches them about why they feel as they do and how to overcome and replace negative habits of mind with positive thoughts. This exercise emphasises the theory of self-determined learning by having students take agency in controlling their choices and decisions and to feel a sense of autonomy and confidence. The goals students choose to focus on are meaningful, so there is an emotional connection which increases their self-belief about their ability to perform a task that they perceive as difficult or impossible to do.

Class application. Ask students to share their passions, dreams and goals, then together co-design activities and assignments that they will commit to taking on. Next help them plan, measure, and adjust their goals and create small milestones to show their progress and celebrate success. This step will increase confidence, courage, and self-efficacy.

Step 7: Belief and reflection

The benefits of reflecting on one’s work are transformational and widely known (Isaacson & Fujita, 2006). For example, at the beginning of class, students write in their journals by redirecting the mind to focus intentionally on the class’s goals, and at the end of the class students journal about what they learned, new ideas, and any questions they have. According to Schön (1983), this reflective practice supports students in becoming lifelong learners, as “when a practitioner becomes a researcher into his practice, he engages in a continuing process of self-education” (p. 299).

Class application. Challenging learning activities and critical thinking assignments help build awareness, self-efficacy, courage, confidence, and communication skills, as well as habits of mind, attitudes, and behaviours necessary to reach their potential. As we conclude the course, students have a choice whether to share their journaling experience and personal growth as part of their final project. Most of the students do so since they are proud of their transformation and eager to share with everyone.

As student B reflected:

Four weeks ago, I remember being so shy I would not like to talk in front of everyone because I would think that whatever I might say or ask might be dumb, but Professor Val, made me feel otherwise. The second day of class I came in wearing heels and that was the first time I would come to class wearing heels and you made me start feeling confident enough to do that. The first skill that I’ve learned is self-control. I will need this in everyday life because instead of talking back or always trying to be right sometimes it is always good to be mature and have self-control. The second skill I’ve learned is critical thinking. This skill will help me achieve things in life because instead of thinking quickly I can take the time to examine and think deeper about things in the near future. The last skill I’ve learned is being strong-minded. This will help me be successful in life because I will not let anyone influence me the way that I feel or think.

Conclusion

Educators have a unique opportunity to design learning environments that prepare people for a future requiring a diverse range of student abilities and needs. Carefully designed assignments encourage students to expand their awareness, to control their choices, and to be responsible for their learning outcomes – to have agency over their learning. Educators can implement diverse learning principles and methods that align with students’ interests and motivation and challenge students to question cultural assumptions and beliefs about their ability and hidden potential. Educators must be knowledgeable of the brain’s neuroplasticity and its effects on learning and how to use it to help students reprogram old beliefs with new ones that support growth and achievement. Our unpredictable world needs proactive, self-directed people with the skills to survive, adjust, and thrive in diverse environments.

References

Becerra, D. (2012). Perceptions of educational barriers affecting the academic achievement of Latino K-12 students. Children & Schools, 34, 167-177. doi:10.1093/cs/cds001

Balfanz, R., & Byrnes, V. (2012). The importance of being in school: A report on absenteeism in the nation's public schools. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 78(2), 4-9.

Blaschke, L.M.. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning. 13, 56-71. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1076.

Blaschke, L.M., & Hase, S. (2015). Heutagogy: A holistic framework for creating 21st century self-determined learners. In M.M. Kinshuk & B.Gros (Eds.), The future of ubiquitous learning: Learning designs for emerging pedagogies. Springer Verlag.

Boumosleh J.M, & Jaalouk D. (2017). Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students- a cross-sectional study. PLos ONE. 12(8):e0182239.

Brandt, B.A. (2013). The learner’s perspective. In S. Hase, & C. Kenyon (Eds.), Self-determined learning: Heutagogy in action (99-116). Bloomsbury Academic.

Brunello, G., & Schlotter, M. (2010). The effect of noncognitive skills and personality traits on labour market outcomes. http://www.epis.pt/downloads/dest_15_10_2010.pdf

Bostic, J. Q., Nevarez, M. D., Potter, M. P., Prince, J. B., Benningfield, M. M., & Aguirre, B. A. (2015). Being present at school: Implementing mindfulness in schools. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 24, 245-259.

Campbell, E. (2013). Research round-up: Mindfulness in schools.

Coker, J. S., Heiser, E., Taylor, L., & Book, C. (2017). Impacts of experiential learning depth and breadth on student outcomes. Journal of Experiential Education, 40(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825916678265

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centred teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113-143. doi:10: 3102/0034655430298563.

De-Sola Gutiérrez, J., Rodríguez de Fonseca, F., & Rubio, G. (2016). Cell-phone addiction: A review. Front Psychiatry, 7, 175.

Duckworth, A. L., & Yeager, D. S. (2015). Measurement matters: Assessing personal qualities other than cognitive ability for educational purposes. Educational Researcher, 44(4), 237–251.

Dovico, A. (2016). Making a S.P.E.C.I.A.L. first impression. Phi Delta Kappa, 98(3), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721716677263

Dweck, C.S. (2008). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

Eberth, J., & Sedlmeier P. (2012). The effects of mindfulness meditation: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 3(3), 174–189.

Ehlers, U.D., & Kellermann, S.A. (2019). Future skills: The future of learning and higher education. Results of the International Future Skills Delphi Survey. Karlsruhe.

Flavell, J.H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive- developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10) doi:10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906.

Goyal Singh, et al, 2014. .Meditation Programs for Psychological Stress and Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):357–368. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

Hase, S. (2014). Skills for the learner and learning leader in the 21st century. In L.M. Blaschke, C. Kenyon, & S. Hase (Eds.), Experiences in self-determined learning, (98-107). Amazon. https://edtechbooks.org/-Kzdo

Hase, S. (2017). Four characteristics of learning leaders. TeachThought. www.teachthought.com/pedagogy/4-characteristics-learning-leaders/

Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2000). From andragogy to heutagogy. UltiBase

Hase, S. (2011). Learner defined curriculum: Heutagogy and action learning in vocational training. Southern Institute of Technology Journal of Applied Research, 1-10

Isaacson, R. M., & Fujita, F. (2006). Metacognitive knowledge monitoring and self-regulated learning: Academic success and reflections on learning. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6, 39-55.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://edtechbooks.org/-puXg

Kang, S.H.K. (2016). Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences.;3(1):12-19. doi:10.1177/2372732215624708

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., & Clifton, J. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Kuhn, D., & Dean, D., Jr. (2004). Metacognition: A bridge between cognitive psychology and educational practice. Theory into Practice, 43(4), 4268-273. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4304_4

Koca, F. (2016). Motivation to learn and teacher-student relationships. Journal of International Education and Leadership, 6(2), 1-20.

Levin, H. M. (2012). More than just test scores. Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 42(3), 269–284.

Ma, Z.F. (2020). Role play as a teaching method to improve student learning experience of a bachelor’s degree programme in a transnational context: an action research study. Compass: Journal of Learning and Teaching. 13. 10.21100/compass.v13i1.1035.

Mezirow, J. (2000). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. John Wiley and Sons.

Robles, M. M. (2012). Executive perceptions of the top 10 soft skills needed in today’s workplace. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569912460400

Rubie-Davies, C. (2012). Teacher expectations and perceptions of student attributes: Is there a relationship? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 121-135.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books, Inc.

Spence, L.D. (2001) The Case Against Teaching, Change. The Magazine of Higher Learning, 33(6), 10-19, DOI: 10.1080/00091380109601822

Velliaris, D. M. (2016). Culturally Responsive Pathway Pedagogues: Respecting the Intricacies of Student Diversity in the Classroom. In González, K., & Frumkin, R. (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Effective Communication in Culturally Diverse Classrooms (pp. 18-38). IGI Global. https://edtechbooks.org/-aqVW

Voinea, L. (2018). Formative assessment as assessment for learning development. Revista de Pedagogie - Journal of Pedagogy. LXVI. 7-23. 10.26755/RevPed/2018.1/7.

World Economic Forum. (2016). The future of jobs: Employment, skills, and workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution. https://edtechbooks.org/-UmG.