When teaching online, instructors often default to using synchronous activities, but asynchronous tools can provide effective learning opportunities in many situations.

"Ugh, I just finished six straight hours of Zoom calls," my exasperated colleague shared on Facebook.

How many of us feel we could win at videoconference bingo because we do it so much?

During the shutdown of in-person education brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, "Zoom hangovers" have become acute for many instructors. However, this fatigue is not simply a COVID-19 challenge but is a struggle that many online teachers have long felt. As colleges and universities move increasing numbers of courses into online or hybrid settings, many instructors mourn the loss of personal connections with students. After all, most of these professionals chose teaching in part because they enjoy student interactions. They often find it unsatisfying to instead teach to a computer screen, with less of a personal relationship with students.

During the shutdown of in-person education brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, "Zoom hangovers" have become acute for many instructors. However, this fatigue is not simply a COVID-19 challenge but is a struggle that many online teachers have long felt. As colleges and universities move increasing numbers of courses into online or hybrid settings, many instructors mourn the loss of personal connections with students. After all, most of these professionals chose teaching in part because they enjoy student interactions. They often find it unsatisfying to instead teach to a computer screen, with less of a personal relationship with students.

The Benefits and Challenges of Synchronous Video

In an effort to develop that connection, many faculty use videoconferencing software, such as Zoom, Google Meet, or Microsoft Teams, because it most closely approximates the in-person teaching experience. Everyone is together at the same time, and the instructor can present ideas, divide the class into breakout rooms, and talk to students "face to face." Synchronous video teaching—video sessions in which everyone participates at the same time—has some powerful benefits, and it does increase the feeling of immediacy and social presence within a class.

However, synchronous video also has serious limitations and cannot be the answer for all online learning. First, it is not convenient for many students, such as those who are at work during class or who live in different time zones. Many of these students seek online learning to find flexibility in how they learn, and synchronous video limits that flexibility.

Second, long synchronous video sessions can be cognitively tiring. Whereas in-person teaching often involves moments of breaking into groups, walking around the room, transitioning from one class to another, and looking away from the professor to take notes during a discussion, during videoconference teaching, all of these things happen sitting in one position, looking at one computer screen.

If done for too long, videoconferencing is a recipe for physical and mental exhaustion. As Suzanne Degges-White wrote, long videoconferencing meetings can be fatiguing: "From a numb butt to an aching back to a dull, throbbing headache and eye strain, hours spent in one position at furniture never designed for long-term sitting can leave us feeling cranky, achy, and a lot worse about life."Footnote1

An Emerging Alternative: Asynchronous Video

How can instructors create the rich, personal connections that benefit student learning without hours of videoconferencing? One strategy is to use asynchronous video. In contrast to videoconferencing, asynchronous video technologies enable students and faculty to record video responses as part of a discussion but without the requirement that it happen at the same time. This means participants can record their videos when and where they want to. It also means they can view others' videos at a time and place of their choosing, or they can break up how they view the videos so that they have important breaks in the middle of the conversation.

Besides increased flexibility, asynchronous video discussions have been found to have many other benefits:

- Rich conversation-like exchanges

- Increased social presence and feeling of immediacy in a class

- Improved student motivation

- Stronger faculty/student relationships

- Improved collaboration and sense of "trust" of group members

- Easier and better feedback on performance

- Increased participation from some groups of students, such as introverts, who prefer asynchronous interaction

Various research studies have cited these benefits, but it is important to note that these studies do not show asynchronous video as a panacea. Indeed, some students appear to prefer text-based discussions. This is not surprising—no two students are the same, and they will have different preferences for how they learn. However, asynchronous video clearly can have a powerful, positive effect in reaching students and developing connections with them in ways that text-based discussions cannot, and it can do this in a much more flexible way than synchronous videoconferencing.

How Can Instructors Use Asynchronous Video?

With any new technology, we may struggle at first to see how asynchronous video can be integrated into our daily work lives. However, we can answer the question of when we could use asynchronous video by first asking "When do I want or need to communicate with others?" If those times of communication require efficiency, often text is faster (although not always—we found in our research that at least sometimes extraverts can feel they communicate faster via video and not everyone is a fast typist). However, if you want to build stronger relationships when communicating with others, and if that communication is at a distance, then asynchronous video may be a great solution. For example, Patrick Lowenthal and his co-authors have discussed how faculty can use asynchronous video as part of their teaching in various ways.Footnote3 They list the following:

- Present questions to a class for students to discuss

- Give feedback on an assignment

- Check in on students doing internships or experiential projects

- Have students provide a quick update on their progress on a project

- Conduct an asynchronous review session for a quiz where students ask questions via video and the instructor responds via video for everyone to see

- Provide tutorials or screencast demonstrations of concepts or procedures

- Conduct brainstorming or ideation sessions, given that asynchronous video allows more time for people to compose their thoughts, reducing the likelihood of groupthink

- Improve student advising and mentoring through weekly or biweekly updates

- Improve alumni outreach by asking alumni to record quick video summaries of their work in a discipline or answers to student questions

- Increase consensus development on a team by asking each team member to share their independent thoughts on an issue

- Enable collaboration across countries and time zones

- Facilitate listening to diverse narratives around a social issue, collected separately but available for students to view and discuss

- Hold "water cooler" chit-chat discussions, given that apps such as Marco Polo and TikTok have already created a rising generation of students who interact casually through video in the same way their parents interacted through letter writing or email

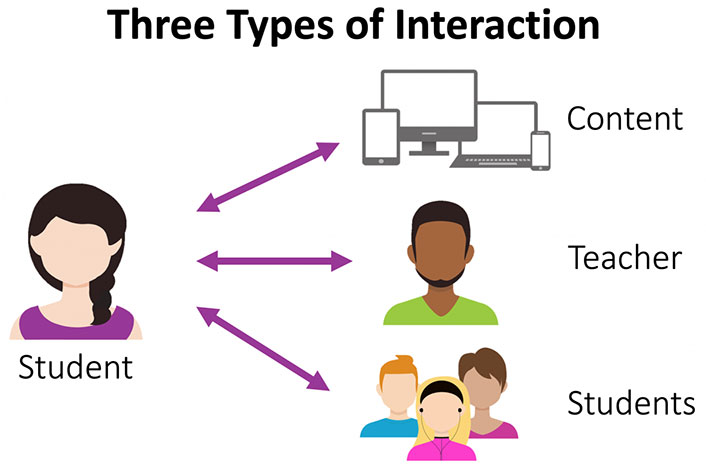

Michael Moore, a pioneer in the discipline of online learning, once argued that there are three important types of interaction in an online course (see figure 1). First, students interact with each other. Second, they interact with the course materials themselves. Third, they interact with their instructor. These three types of interaction can be a guide to using asynchronous video effectively in online learning.

Figure 1. Three types of interactions in online learning (Jered Borup, from K–12 Blended Teaching, CC BY 2.0)

Figure 1. Three types of interactions in online learning (Jered Borup, from K–12 Blended Teaching, CC BY 2.0)

How can asynchronous video assist online courses? By improving how students interact with the learning content (through viewing content, instead of just reading it), improving how they interact with each other (through discussions, collaborations, and informal talk), and improving how they interact with their instructors (through question-and-answer activities and advising). Asynchronous video is not the only means to do these things, but it can be an effective way to add needed variety to the monotony of text-based discussions and videoconferencing fatigue, while still honoring the flexibility that has made online learning appealing.

Acknowledgment

This chapter was written with the support of EdConnect and previously published at https://edtechbooks.org/-dBJy.

Notes

Amy Pavel, Dan B. Goldman, Björn Hartmann, and Maneesh Agrawala, "VidCrit: Video-Based Asynchronous Video Review," Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, October 2016, 517–528).

Cynthia Clark, Neal Strudler, and Karen Grove, "Comparing Asynchronous and Synchronous Video vs. Text Based Discussions in an Online Teacher Education Course," Online Learning 19 no. 3 (2015): 48–69;

Jered Borup, Charles R. Graham, and Andrea Velasquez, "The Use of Asynchronous Video Communication to Improve Instructor Immediacy and Social Presence in a Blended Learning Environment," in Blended Learning across Disciplines: Models for Implementation, ed. Andrew Kitchenham (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2011), 38–57;

Jered Borup, Richard E. West, and Charles R. Graham, "Improving Online Social Presence through Asynchronous Video," The Internet and Higher Education 15, no. 3 (2012): 195–203;

Kori Inkpen, Honglu Du, Asta Roseway, Aaron Hoff, and Paul Johns, "Video Kids: Augmenting Close Friendships with Asynchronous Video Conversations in VideoPal," Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2012, 2,387–2,396;

Michael E.Griffiths and Charles R. Graham, "The Potential of Asynchronous Video in Online Education," Distance Learning 6 no. 2 (2009): 13;

Michael E. Griffiths and Charles R. Graham, "Using Asynchronous Video to Achieve Instructor Immediacy and Closeness in Online Classes: Experiences from Three Cases," International Journal on E-Learning 9 no. 3 (January 2010): 325–340;

Patrick Lowenthal, Jered Borup, Richard E. West, and Leanna Archambault, "Thinking Beyond Zoom: Using Asynchronous Video to Maintain Connection and Engagement during the COVID-19 Pandemic," Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 28 no. 2 (2020): 161–169.

Suzanne Degges-White, "Zoom Fatigue: Don't Let Video Meetings Zap Your Energy," Psychology Today, April 4, 2020.