Standard 7.3: Writing the News: Different Formats and Their Functions

Explain the different functions of news articles, editorials, editorial cartoons, and “op-ed” commentaries. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T7.3]

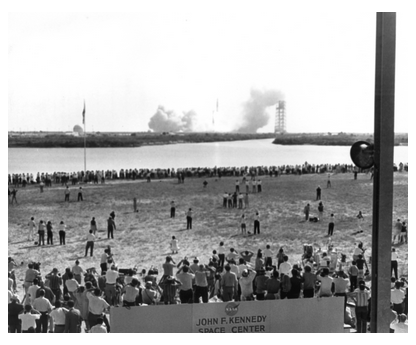

News Reporters Watch the Launch of the Apollo 11 Moon Mission (July 15, 1969),

News Reporters Watch the Launch of the Apollo 11 Moon Mission (July 15, 1969),

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration), Marshall Image Exchange, Public DomainFOCUS QUESTION: What are the Functions of Different Types of Newspaper Writing?

Newspapers include multiple forms of writing, including news articles, editorials, editorial cartoons, Op-Ed commentaries, and news photographs. Each type of writing has a specific style and serves a particular function.

News articles report what is happening as clearly and objectively as possible, without bias or opinion. In reporting the news, the Society of Professional Journalists Code of Ethics demands that reporters:

- Seek truth and report it

- Minimize harm

- Act independently

- Be accountable and transparent

Editorials, Editorial Cartoons, and Op-Ed Commentaries are forums where writers may freely express their viewpoints and advocate for desired changes and specific courses of action. In this way, these are forms of persuasive writing. Topic 4/Standard 6 in this book has more about the uses of persuasion, propaganda, and language in political settings.

Photographs can be both efforts to objectively present the news and at the same time become ways to influence how viewers understand people and events. Press Conferences are opportunities for individuals and representatives of organizations to answer questions from the press and present their perspectives on issues and events. Sports Writing is an integral part of the media, but the experiences for women and men journalists are dramatically different.

Check out Reading and Writing the News in our Bookcase for Young Writers for material on the history of newspapers, picture books about newspapers, and digital resources for reading and writing the news.

As students learn about these different forms of news writing, they can compose their own stories and commentaries about local and national matters of importance to them

1. INVESTIGATE: News Articles, Editorials, Editorial cartoons, Op-Ed Commentaries, Photographs, Press Conferences, and Sports Writing

Reporters of the news are obligated to maintain journalistic integrity at all times. They are not supposed to take sides or show bias in written or verbal reporting. They are expected to apply those principles as they write news articles, editorials, editorial cartoons, Op-Ed commentaries, take news photographs, and participate in press conferences.

You can find resources for Reading and Writing the News in Chapter 6 of our Bookcase for Young Writers.

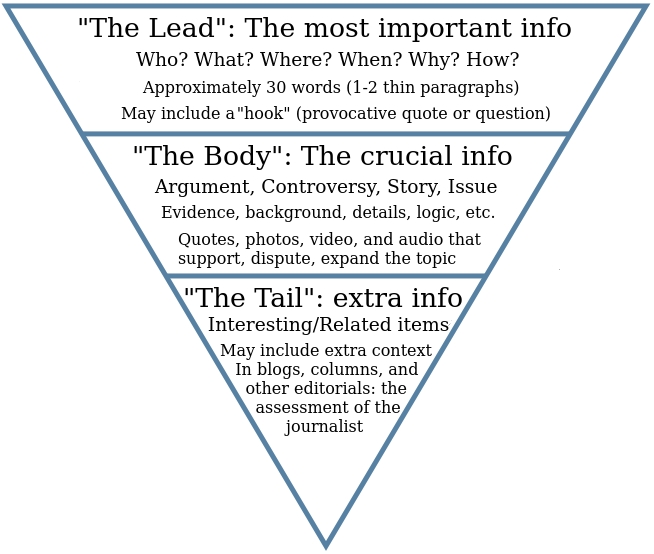

News Articles and the Inverted Pyramid

News articles follow an Inverted Pyramid format. The lead, or main points of the article—the who, what, when, where, why and how of a story—are placed at the top or beginning of the article. Additional information follows the lead and less important, but still relevant information, comes after that. The lead information gets the most words since many people read the lead and then skim the rest of the article.

“Inverted pyramid in comprehensive form” by Christopher Schwartz is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

“Inverted pyramid in comprehensive form” by Christopher Schwartz is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0Editorials

Editorials are written by the editors of a newspaper or media outlet to express the opinion of that organization about a topic. Horace Greeley is credited with starting the “Editorial Page” at his New York Tribune newspaper in the 1840s, and so began the practice of separating unbiased news from clearly stated opinions as part of news writing (A Short History of Opinion Writing, Stony Brook University).

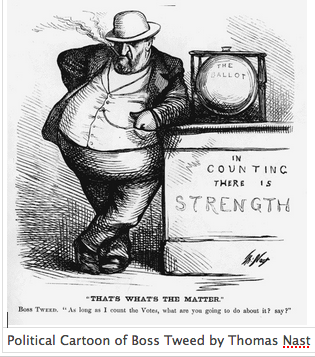

Editorial or Political Cartoons

Editorial cartoons (also known as political cartoons) are visual images drawn to express opinions about people, events, and policies. They make use of satire and parody to communicate ideas and evoke emotional responses from readers.

There are differences between a cartoon and a comic. A “cartoon usually consists of a single drawing, often accompanied by a line of text, either in the form of a caption underneath the drawing, or a speech bubble.” A comic, by contrast, “comprises a series of drawings, often in boxes, or as we like to call them, ‘panels,’ which form a narrative” (Finck, 2019, p. 27).

Caricature of Boss Tweed, by Thomas Next, {{PD-art-US}}

Caricature of Boss Tweed, by Thomas Next, {{PD-art-US}}An exhibit from the Library of Congress noted how political or editorial cartoons are “no laughing matter.” They are “pictures with a point” (It's No Laughing Matter: Political Cartoons/Pictures with a Point, Library of Congress). Washington Post cartoonist Ann Telnaes stated: “The job of the editorial cartoonist is to expose the hypocrisies and abuses of power by politicians and powerful institutions in our society” (Editorial Cartooning, Then and Now, Medium.com, August 7, 2017).

Benjamin Franklin published the first political cartoon, “Join, or Die” in the Pennsylvania Gazette, May 9, 1754. Thomas Nast used cartoons to expose corruption, greed, and injustice in Gilded Age American society in the late 19th century. Launched in 1970 and still being drawn today in newspapers and online, Doonesbury by Gary Trudeau provides political satire and social commentary in a comic strip format. In 1975, Doonesbury was the first politically-themed daily comic strip to win a Pulitzer Prize. Editorial and political cartoons are widely viewed online, especially in the form of Internet memes that offer commentary and amusement to digital age readers.

Commentators including Communication professor Jennifer Grygiel have claimed that memes are the new form of political cartoons. Do you think that this is an accurate assertion? Compare the history of political cartoons outlined above with your own knowledge of memes to support your argument. What are the different perspectives?

Op-Ed Commentaries

Op-Ed Commentaries (Op-Ed means "opposite the editorial page") are written essays of around 700 words found on, or opposite, the editorial page of newspapers and other news publications. They are opportunities for politicians, experts, and ordinary citizens to express their views on issues of importance. Unlike news articles, which are intended to report the news in an objective and unbiased way, Op-Ed commentaries are opinion pieces. Writers express their ideas and viewpoints, and their names are clearly identified so everyone knows who is the author of each essay. The modern Op-Ed page began in 1970 when the New York Times newspaper asked writers from outside the field of journalism to contribute essays on a range of topics (The Op-Ed Page's Back Pages, Slate, September 27, 2010). Since then, Op-Ed pages have become a forum for a wide expression of perspectives and viewpoints.

News Photographs

Photographs are a fundamental part of newspapers today. We would be taken back and much confused to view a newspaper page without photographs and other images including charts, graphs, sketches, and advertisements, rendered in black and white or color. Look at the front page and then the interior pages of a major daily newspaper (in print or online) and note how many photographs are connected to the stories of the day.

The first photograph published in a US newspaper was on March 4, 1880. Prior to then, sketch artists created visual representations of news events. The New York Illustrated News began the practice of regularly featuring photographs in the newspaper in 1919 (Library of Congress: An Illustrated Guide/Prints and Photographs).

From that time, photography has changed how people receive the news from newspapers. The 1930s to the 1970s have been called a "golden age" of photojournalism. Publications like the New York Daily News, Life, and Sports Illustrated achieved enormous circulations. Women became leaders in the photojournalist field: Margaret Bourke-White was a war reporter; Frances Benjamin Johnson took photos all over the United States; Dorothea Lange documented the Great Depression; the site Trailblazers of Light tells the hidden histories of the pioneering women of photojournalism. Also check out "What Is The Role of a War Correspondent?" later in this topic.

For an engaging student writing idea, check out A Year of Picture Prompts: Over 160 Images to Inspire Writing from the New York Times.

Press Conferences

A press conference is a meeting where news reporters get to ask public figures and political leaders (including the President of the United States) questions about major topics and issues. In theory, press conferences are opportunities for everyone in the country to learn important information because reporters ask tough questions and political leaders answer them openly and honestly. In fact, as Harold Holzer (2020) points out in the study of The Presidents vs. The Press, there has always been from the nation's founding "unavoidable tensions between chief executives and the journalists who cover them."

President George W. Bush responds to questions during his final press conference in the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room of the White House | Public Domain

President George W. Bush responds to questions during his final press conference in the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room of the White House | Public DomainThe first Presidential press conference was held by Woodrow Wilson in 1913. Calvin Coolidge averaged about 74 press conferences annually during his Presidency, although these were informal, off-the-record conversations and reporters could not use the information without the President's permission.

Every President since has met with the press in this conference format, although the meetings continued to be "off the record" (Presidents could not be quoted directly) until the Eisenhower Presidency. In March 1933, Eleanor Roosevelt was the first First Lady to hold a formal press conference. President Eisenhower held the first televised press conference on January 19, 1955.

John F. Kennedy transformed the Presidential Press Conference into a media event; you can watch the video of Kennedy's first televised press conference here.

Franklin D. Roosevelt held the most press conferences (881; twice a week during the New Deal and World War II); Richard Nixon the fewest (39) (quoted from Presidential Press Conferences, The American Presidency Project).

Donald Trump changed the news conference format dramatically, often turning meetings with the press into political campaign-style attacks on reporters, "fake news," and political opponents. He regularly answered only the questions he wanted to answer while walking from the White House to a waiting helicopter; this "chopper talk" -- in Stephen Colbert's satirical term, since it does not have a formal question and answer format -- enabled the President to tightly control the information he wanted to convey to the public (Politico, August 28, 2019).

Presidents are not the only ones who participate in press conferences. Public officials at every level of government are expected to answer questions from the news media. Corporate executives, sports figures and many other news makers also hold press conferences. All of these gatherings are essential to providing free and open information to every member of a democratic society, but only when reporters ask meaningful questions and public officials answer them in meaningful ways.

Sports Writing/Sports Journalism

Sports writing is the field of journalism that focuses on sports, athletes, professional and amateur leagues, and other sports-related issues (Sports Writing as a Form of Creative Nonfiction). Sports writing in the U.S. began in the 1820s, with coverage of horse racing and boxing included in specialized sports magazines. As newspapers expanded in the 19th century, the so-called “penny press,” editors and readers began demanding sports content. In 1895, William Randolph Hearst introduced the first separate sports section in his newspaper, The New York Journal (History of Sports Journalism: Part 1).

Throughout the 20th century, sports writing emerged as a central part of print newspapers and magazines (the famous magazine Sports Illustrated began in 1954). Reporters and columnists followed professional teams, often traveling with them from city to city, writing game stories and human interest pieces about players and their achievements.

Earl Warren, the former Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, is reported to have said that he always read the sports pages of the newspaper first because “the sport section records people’s accomplishments; the front page has nothing but man’s failures.” Warren’s comment speaks to the compelling place that sports have in American culture, daily life, and media. Millions of people follow high school sports, college teams, and professional leagues in print and online media.

Importantly, as the blogger SportsMediaGuy points out, Earl Warren’s quote can be read as if the sports and sports pages were an escape room where only positive things happen and the inequalities and inequities of society never intrude. Nothing can be further from everyday reality. Sports mirror society as a whole, and issues of class, race, gender, economics, and health are present on playing fields, in locker rooms, and throughout sports arenas.

The history of women sportswriters is a striking example of how the inequalities of society manifest themselves in sports media. Women have been writing about sports for a long time, however, not many people know the history. Sadie Kneller Miller was the first known woman to cover sports when she reported on the Baltimore Orioles in the 1890s, but "with stigma still attached to women in sports, Miller bylined her articles using only her initials, S.K.M., to conceal her gender" (Archives of Maryland - Sadie Kneller Miller, para. 3).

Between 1905 and 1910, Ina Eloise Young began writing about baseball for the local Trinidad, Colorado newspaper before moving on to the Denver Post where she became a “sporting editor” in 1908, covering the town’s minor league team and the 1908 World Series (Our Lady Reporter’: Introducing Women Baseball Writers, 1900-30). New Orleans-based Jill Jackson became one of the few female sports reporters on television and radio in the 1940s (Jill Jackson: Pioneering in the Press Box). Phyllis George, the 1971 Miss America pageant winner, joined CBS as a sportscaster on the television show The NFL Today in 1975.

The histories of women writing about sports revealed the tensions of sexism and gender discrimination. Many of the early female sports reporters encountered various levels of threatening and harmful treatment upon entering the locker room. Some were physically assaulted. Others were sexually abused or challenged by the players in sexually inappropriate ways (Women in Sports Journalism, p.iv).

You can read more in Lady in the Locker Room by Susan Fornoff who spent the majority of the 1980s covering the Oakland Athletics baseball team and listen to a 2021 podcast in which Julie DiCaro discusses her new book, Sidelined: Sports, Culture and Being a Woman in America.

Women today continue to face widespread gender discrimination in what is still a male-dominated sports media. In 2019, 14% of all sports reporters are women and women’s sports only account for about 4% of sports media.

Media Literacy Connections: News Photographs & Newspaper Design

Photographs in print newspapers and online news sites convey powerful messages to readers and viewers, but they are not to be viewed uncritically.

Every photo represents a moment frozen in time. What happened before and after the photo was taken? What else was happening outside the view of the camera? Why did the photographer take the photo from a certain angle and perspective? Why did a newspaper editor choose to publish one image and not another?

The meaning of a news photograph depends on multiple levels of context as well as how each of us interpret its meaning.

The following activities will provide you with an opportunity to act as a critical viewer of newspaper photographs and as a member of a newspaper design team who must decide what photographs to incorporate in a class newspaper.

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTubeSuggested Learning Activities

- Compare and Contrast Women and Men Sports Reporters and Columnists

- Research how many female reporters and columnists write in the newspapers your family members read compared to male reporters and columnists. For example, in March 2021, the Boston Globe had one woman reporter, Nicole Yang and one woman sports columnist, Tara Sullivan.

- What differences to you see in the topics and sports that women reporters and columnists cover and write about?

- Examine the roles that women reporters have on local and network sports television.

- What differences to you see in their roles and the roles of male reporters?

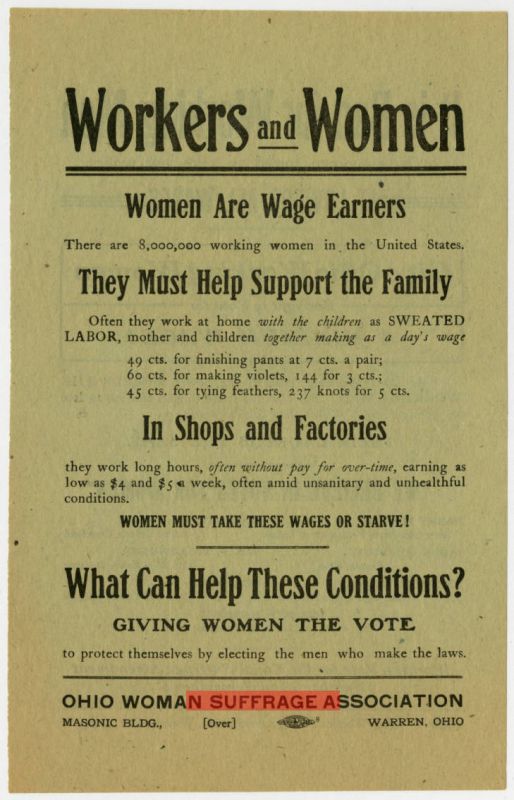

- Compose a Broadside About a Historical or Contemporary Issue

- A broadside is a strongly worded informational poster that spreads criticisms of people or policies impacting a group or community. It contains statements attacking a political opponent or political idea, usually displayed on single large sheets of paper, one side only, and is designed to have an immediate emotional impact on readers.

Workers and women broadside Ohio Woman Suffrage Association | Public Domain

Workers and women broadside Ohio Woman Suffrage Association | Public DomainTeacher-Designed Learning Plan: Composing Broadsides

History teacher Erich Leaper has students construct broadsides as a learning activity when teaching Op-Ed Commentaries. During colonial times, proponents of the American Revolution posted broadsides expressing their opposition to British colonial acts and policies. Broadsides were the social media and Op-Ed commentaries of the time.

Steps to follow:

- Begin by asking students to list actions or activities that are likely to upset you.

- Students in groups select one of five options: the Tea Act, Sugar Act, Stamp Act, Intolerable Acts, Quartering Act, and the Townshend Act.

- The teacher writes a broadside as a model for the students. Erich wrote his about the Sugar Act, entitling it "Wah! They Can't Take Away My Candy!"

- Researching and analyzing one of the acts, each group writes and draws a broadside expressing opposition to and outrage about the unfairness of the law.

- Each broadside has

- 1) An engaging title (like "Taxing Tea? Not for Me!" or "Call Them What They Are--Intolerable" or "Stamp Out Injustice"

- 2) Summary of its claim in kid-friendly language;

- 3) A thesis statement of the group's viewpoint; and

- 4) At least 3 statements of outrage or opposition.

- Groups display their broadside posters around the classroom or in a virtual gallery.

- In their groups, students view all of the other broadsides and discuss how they would rate the Acts on an oppressiveness scale—ranging from most oppressive to least oppressive to the colonists.

- The assessment for the activity happens as each student chooses the top three most oppressive acts and explain her/his choices in writing.

Resources for writing colonial broadsides:

Online Resources for Newspapers

2. UNCOVER: Pioneering Women Cartoonists and Animators: Jackie Ormes, Dale Messick, and More

The pioneering work of women cartoonists and animators is part of the overlooked and largely unknown history of technology and media in the mid-20th century.

Zelda “Jackie” Ormes is considered to be the first African American woman cartoonist. In comic strips that ran in Black-owned newspapers across the country in the 1940s and 1950s, she created memorable independent women characters, including Torchy Brown and Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger. Her characters were intelligent, forceful women and their stories addressed salient issues of racism and discrimination in African American life. In 1947, a Patty-Jo doll was the first African American doll based on a comic character; there was also a popular Torchy Brown doll.

Google honored Jackie Ormes with a Google Doodle slideshow and short biography on September 1, 2020.

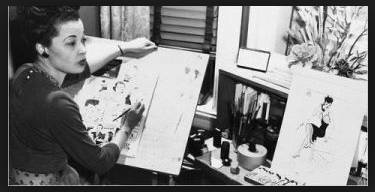

Jackie Ormes in her Studio, Public Domain

Jackie Ormes in her Studio, Public Domain Dale Messick, a pioneering female cartoonist, debuted the comic strip, Brenda Starr, Reporter on June 30, 1940. The comic ran for more than 60 years in hundreds of newspapers nationwide. Throughout its history, the creative team for the comic strip were all women, including the writers and artists who continued the strip after Messick retired in 1980. Based on the character, style, and beauty of Hollywood actress Rita Haywood, Brenda Starr was determined and empowered, lived a life of adventure and intrigue, and always got the news story she was investigating.

Joye Hummel was the first woman hired to write Wonder Woman comics - she wrote every episode between 1945 and 1947, but the writing credit went to "Charles Moulton," a pen name for William Moulton Marston, the inventor of the lie-detector test and the creator and first writer of the comic series. Hummel passed away in 2021 at age 97. A whole series of women (including birth-control pioneer Margaret Sanger's niece) were responsible for the development of the comic, noted historian Jill Lepore in her book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman (2015), which documented the evolution of the character from a strong feminist into a more male-like superhero.

Women also contributed immensely to cartoon animation and the development of animated films. Lillian Friedman Astor, who animated characters including Betty Boop and Popeye, is considered the first American woman studio animator -- all of her animation work was uncredited.

Watch an interview featuring Lillian Friedman Astor below. Retta Scott who worked on the movie Bambi and later produced Fantasia and Dumbo, was the first woman to receive screen credit as an animator on a Disney film.

To learn more, check out 7 Women Who Shaped Animated Films (and Childhoods), Medium (August 8, 2019).

Watch on YouTube

Watch on YouTube

Suggested Learning Activity

Assess the Historical Impact of Jackie Ormes, Dale Messick and Other Women Cartoonists and Animators

State Your View: Why is it difficult for women to enter and succeed in professions where there are mostly men?

3. ENGAGE: How Are War Correspondents and War Photographers Essential to a Free Press?

War Correspondents and War Photographers have one of the most important and most dangerous roles in the news media. They travel to war zones, often right into the middle of actual fighting, to tell the rest of us what is happening to soldiers and civilians. Without their written reports and dramatic photos, the public would not know the extent of military activities or the severity of humanitarian crises.

War Correspondent Alan Wood typing a dispatch in a wood outside Arnhem; September 18, 1944, Public Domain

War Correspondent Alan Wood typing a dispatch in a wood outside Arnhem; September 18, 1944, Public DomainWar correspondence has a fascinating history. The Roman general Julius Caesar was the first war correspondent. His short, engagingly written accounts of military victories made him a national hero and propelled his rise to power (Welch, 1998). As a young man in the years between 1895 and 1900, Winston Churchill reported on wars in Cuba, India, the Sudan, and South Africa (Read, 2015).

Thomas Morris Chester, the only Black war correspondent for a major newspaper at the time of the Civil War, reported on the activities of African American troops during the final year of the war in Virginia for the Philadelphia Press (Blackett, 1991). He had been a recruiter for the 54th Massachusetts regiment - the first unit of African American soldiers in the North during the Civil War.

America's first female war correspondent was Nellie Bly who covered World War I from the front lines for five years for the New York Evening Journal. Peggy Hull Deuell was the first American woman war correspondent accredited by the U.S. government. Between 1916 and the end of World War II, she sent dispatches from battlefields in Mexico, Europe and Asia.

For 28 years, Martha Gellhorn covered fighting in the Spanish Civil War, World War II, Vietnam, the Middle East and Central America. Combat photojournalist Dickey Chapelle was the first American female war photographer killed in action in World War II. Catherine Leroy was the only non-military photographer to make a combat jump into Vietnam with the Sky Soldiers of the 173rd Airborne Brigade. You can read more about Catherine Leroy, Frances Fitzgerald, and Kate Webb during the Vietnam War in the book You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War by Elizabeth Becker (Public Affairs, 2021).

Women have played essential roles in documenting the events of war. At the end of August, 1939, British journalist Clare Hollingworth was the first to report the German invasion of Poland that began World War II, what has been called "probably the greatest scoop of modern times" (as cited in Fox, 2017, para. 6). It was her first week on the job (Garrett, 2016). In her book The Correspondents, reporter Judith Mackrell (2021) profiles the experiences of six women writers on the front lines during World War II: Martha Gellhorn, Clare Hollingworth, Lee Miller, Helen Kirkpatrick, Virginia Cowles, and Sigrid Schultz. These women faced the dangers of war and the bias of sexism, often having to hitchhike to the battlefield to get the story in defiance of rules against women in combat zones. You can go here to learn more about the pioneering women of photojournalism (CNN, March 8, 2023).

War correspondents and photojournalists face and sometimes met death. Ernie Pyle, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his stories about ordinary soldiers during World War II, was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire in 1945. Marie Colvin, who covered wars in Chechnya, Sri Lanka, and the Middle East was killed by the Syrian government shelling in 2012. When asked why she covered wars, Marie Colvin said, “what I write about is humanity in extremis, pushed the unendurable, and that it is important to tell people what really happens in wars—declared and undeclared” (quoted in Schleier, 2018, para. 8).

How did the lives and deaths of these two reporters and their commitment to informing others about war reflect the role and importance of a free press in a democratic society?

Media Literacy Connections: How Reporters Report Events

Print and television news reporters make multiple decisions about how they report the events they are covering, including who to interview, which perspective to present, which camera angles to use for capturing footage, and which audio to record. These decisions structure how viewers think about the causes and consequences of events.

"Hong Kong protest Admiralty Centre" by Citobun is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

"Hong Kong protest Admiralty Centre" by Citobun is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0In one notable historical example, historian Rick Perlstein (2020) described how, during the beginning of the Iran Hostage Crisis in 1979, ABC News vaulted to the top of the TV news show ratings with its late night broadcasts of "America Held Hostage: The Crisis in Iran" (the show that would soon be renamed Nightline). The network focused on showing images of a burning American flag, embassy employees in blindfolds, Uncle Sam hanged in effigy, and increasingly more people watched the broadcast. Perlstein (2020) noted, "the images slotted effortlessly into the long-gathering narrative of American malaise, humiliation, and failed leadership" (p. 649) - themes Ronald Reagan would capitalize on during his successful 1980 Presidential campaign.

In the following activities, you will examine reporters' differences in coverage of the 2016 Hong Kong Protests and then you will act as a reporter and create or remix the news.

Suggested Learning Activities

- Write a People's History of a War Reporter

- Describe the life of Marie Colvin, Ernie Pyle, Dickey Chapelle or another war journalist or photographer and highlight their time spent covering war (see the online resources section below for related information).

- Compare and Contrast

- How do the lives and jobs of modern war correspondents compare and contrast to those in different historical time periods (i.e. American Revolution, the World War II, Vietnam War).

- Engage in Civic Action

- Design a Public Service Announcement (PSA) video or podcast to convince politicians to provide war correspondents with mental health care support and services once they return from reporting in a war zone.

- Research and Report

- In 2019, the U.S. was engaged in military operations in 7 countries: Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, Libya, and Niger.

- What do you and people in general know about these engagements? How are war correspondents covering these wars?

Online Resources for War Correspondents and Photojournalists

Standard 7.3 Conclusion

INVESTIGATE looked at news articles, editorials, political cartoons, Op-Ed commentaries, news photographs, and press conferences as formats where writers and artists report the news and also present their opinions and perspectives on events. ENGAGE explored the roles of war correspondents, using the historical experiences of Marie Colvin (writing 1979 to 2012) and Ernie Pyle (writing 1925 to 1945) as examples. UNCOVER told the stories of two important feminist comic strips drawn by pioneering women cartoonists, Jackie Ormes (writing 1930 to 1956) and Dale Messick (writing 1940 to 1980).