Learning Outcomes

After reading this chapter, you should be able to

- define basic terms of rhetoric (argument, emotion, character, and style) and see examples of these in the world around you

- define the elements of the rhetorical triangle (writer, audience, message, and purpose) and recognize how those are influenced by (and influence) the context in which we write

- use various methods of invention, organization, and style to adapt written and oral forms of communication to specific rhetorical situations.

2.1 You're Not a Blank Slate

If you look over the learning outcomes for this chapter, do any of those terms and ideas sound familiar to you? Do they bring back memories of your first-year college writing class? Or maybe of high school English classes?

You're embarking on an advanced writing course, but I doubt this is your first encounter with being taught about writing. In fact, I hope you've had many encounters with writing teachers and assignments, and it's important to note that you've got a lot of experience with writing already under your belt. The purpose of this chapter is to lay a basic foundation of concepts about writing (which we'll frame in terms that are usually associated with the study of rhetoric). Much of what you read in this chapter may sound familiar to you, especially if you took a first-year writing course at BYU and studied from the textbook commonly assigned in that course.

But if this is your first writing class in college or if the mention of words like rhetoric or audience or genre make your heart race a bit and your palms sweat, don't worry! You're not coming at this as a complete novice—you've had lots of experience with the concepts of this chapter already. For instance, deciding whether to ask someone out via text message or in person, thinking about the best way to approach that roommate who always eats your food, biting your tongue in front of the cop who just pulled you over– in all these situations you're practicing the concepts we'll discuss here because you're making decisions about how to use the available tools to best communicate.

The goal of this chapter is to give you some terms and definitions that will tap into both your previous writing instruction and your personal experience with communication in general. We'll explore some examples to help connect those ideas to real-world situations and, hopefully, to remind you of ways that you've applied these principles yourself. Then, the rest of the text will build on that foundation as we focus your attention on specific situations you’ll likely encounter working in your field of study.

Recall from FYW

What do you remember learning in your first-year writing course? (Or, if you didn't have a first-year writing course, think about the last writing course you can remember.) What concepts stood out, what practices did you adopt as a result of this course?

2.2 Fundamental Writing Tools

Let me share with you one of my fundamental truths about writing: Good writing is about making good choices. What does that mean? You may have already noticed that this chapter has a different feel from the previous chapter—that "feel" is something we sometimes call voice (which we'll get to more in a little bit when we talk about style later in this section). My voice as a writer comes from the choices I make that would be different from the choices a different writer might make. You'll notice this throughout this textbook, in fact: Each person who contributes to the book has a different voice because we make different choices in our writing.

The best writers have a large tool chest available to them, and they make purposeful and effective choices about which tools to use in a given situation. Just as a good carpenter recognizes when a saw is needed versus a plane, a good writer knows when to use an anecdote versus results from an empirical study.

In this section we want to review some of the tools we use to persuade, inform, or otherwise communicate with others. In your first-year writing (FYW) class, it's likely that you studied these tools by examining how other people used them and then practiced using them yourself in your own writing. In many ways, you’ll engage in similar work in this course, but within the specific context of your field of study.

Evidence and Reasoning

One of the most important choices we make as writers is related to the evidence we use to support our claims and how we connect that evidence. Many of the texts we read and write try to inform or persuade an audience and the kind of evidence we use is critical to that purpose. Strong writers rely on sound thinking, logically connected claims and reasons, and clearly articulated assumptions that support this thinking. (Some of you may have had teachers in the past use the term logos to talk about this kind of reasoning, which is a Greek word. We'll stick with the English terms in this book.)

Photo by CDC on Unsplash

Photo by CDC on Unsplash

The role of evidence and reasoning is absolutely fundamental to so much of our communication in the world. Take the issue of vaccinating children, which lately has become an intensely debated issue. Those in favor of vaccinations base their arguments on scientific evidence and principles; their underlying assumption is that the methods of science build solid knowledge that helps us control the world around us (i.e., prevent horrible diseases from infecting people).

Those opposed to vaccinations (often called "anti-vaxxers") use a different kind of logic, attributing causal power, for instance, to correlated events (my grandson was fine before the vaccine but then after was diagnosed with autism); they assume that these coincidences prove causality and that the doctors and big vaccine makers are in cahoots. There exists a fundamental disconnect in the way most health care professionals reason about vaccines and the way anti-vaxxers do, and that's connected to the underlying assumptions both make about what constitutes knowledge you can trust.

Discussion Question

Character

In looking at character, we’re focused on the persona we build as communicators–on our credibility as a writer or speaker. (Some of you may be familiar with the Greek term ethos, which is how the Greeks referred to this idea of character.) How do we convey a sense of expertise to an audience so they trust what we’re saying? How do we connect with our audience in ways that help us achieve our purpose? Our messages will be more effective if our audience has reasons to trust us. We build this trust through demonstrating that we’re knowledgeable about a topic, presenting a balanced view of the issue, and sharing personal experiences as appropriate that connect us with our audience.

Don't make it so you have to wear a hat everywhere. Get your information from good sources. Photo by Allef Vinicius on Unsplash

Don't make it so you have to wear a hat everywhere. Get your information from good sources. Photo by Allef Vinicius on UnsplashThis issue of character seems to be more and more important. One student I was working with searched the Internet looking for solutions to an outbreak of acne on her forehead; in an online forum, she read a suggestion to use a Mr. Clean cleaning pad on the affected skin. The result was a chemical burn on her forehead that was much worse (and more noticeable) than the pimples. Why would this student put her trust in an unknown contributor to an online forum rather than a medical expert? I'm guessing she was probably in a hurry and paid a (painful) price for ignoring credibility. While good readers should work to assess the character of an information source, as writers we can help them and ourselves out by attending to how to build our character.

Discussion Question

Emotion

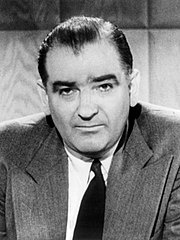

Joseph McCarthy (Public Domain)

Joseph McCarthy (Public Domain)

Emotions are powerful tools in communicating, and as such should be used carefully. Emotional appeals to an audience through specific stories and concrete details and specific word choices can evoke the proper feelings in an audience and propel them to action. (Again, some of you may be familiar with the term pathos, which the ancient Greeks used to refer to these appeals to emotion.)

However, these appeals to emotion can also be abused to manipulate an audience into wrong or inappropriate thought or action. Joseph McCarthy, a senator from Wisconsin in the 1950s, ruined many careers in and out of politics when he accused many people of being Communist sympathizers. He played on anxieties felt by many about the spread of this ideology and the growing power of the USSR, but in the end there was little real evidence to prove either the veracity of his claims or the threat that these alleged sympathizers posed. (In fact, so disgusted was the public with his manipulative tactics that we now have the term McCarthyism to describe making accusations without real evidence.) As a speaker and writer, it’s up to you to ensure that you use rhetorical tools like emotional appeals ethically and responsibly—you don’t want your name becoming associated with dastardly, underhanded deeds!

Discussion Question

Style

Your writing style is as unique as the way you dress. Photo by Amanda Vick on Unsplash

Your writing style is as unique as the way you dress. Photo by Amanda Vick on UnsplashFinally, there’s the Style of our message, or how we communicate a message–the words and sentences we use. Just as many of us choose to dress a certain way (to reflect our personality perhaps or influence the impression we have on others), we "dress" our message in a certain way through our use of language. Remember my note earlier that the different authors who contribute to this book make different choices with our language—that gives each of us our style. (Case in point: Note that I chose to use a dash in that last sentence, which is not the same choice other writers would make.)

It’s important that we adhere to standard English conventions in our spelling and punctuation and sentence structure; writing that’s riddled with errors reflects poorly on the writer. How many flame wars have been started on the Internet because someone used your instead of you’re or there instead of their? At the same time, we want to hone the power of our sentences by using sophisticated techniques that can impact a reader. We can enhance our style by studying the best writers (both in our discipline and outside of it) and taking careful note of how these writers achieve certain effects with the sentences they craft.

While you'll read much more about style later in this text, it's worth noting here that many audiences value concise writing that's not pretentious. This is especially true when we write for general audiences, and it's actually part of what informs our character. As writers we should strive to make even complex ideas as intelligible as possible, and we should attend to word choice and sentence structure as important tools in this goal. A great example of this actually comes from government, where agencies are actually required by law to write plainly and clearly. Look at the two sentences below, taken from the government's guidelines for plain language:

|

Don't Say

|

Say

|

|

These sections describe types of information that would satisfy the application requirements of Circular A-110 as it would apply to this grant program.

|

These sections tell you how to meet the requirements of Circular A-110 for this grant program.

|

Note how much more direct the second sentence is, and note the choices that are made to bring about that clarity (such as the choice in the second example to focus on the reader's action through using the pronoun "you"). Clear, concise writing can be more appealing to audiences and can strengthen their opinion of you as a writer.

2.3 The Rhetorical Situation

Who's your audience for your journal? Photo by Jan Kahánek on Unsplash

Who's your audience for your journal? Photo by Jan Kahánek on UnsplashWhen I was 11 and 12 years old, I was very good at keeping a journal; I wrote nearly every day. When I wrote in that journal, I'm not sure I ever expected anyone to read my daily entries, but I did hold on to the journal through the years. Today, my children like to read those entries and tease me about them (they are admittedly immature and pretty silly, but then I was a kid, so what do you expect?). I like to complain to them that if I had known that my future children would read it, I either would never have kept a journal or I would have tried to sound more mature in it.

If you keep (or have kept) a journal, perhaps you've wondered if anyone else would ever read what you wrote–maybe you've hoped that they wouldn't! It's an odd thing, keeping a journal: I started off many of my entries in that journal with the phrase "Dear Journal," and I wonder today if I really imagined some real audience on the other end of my writing. As I consider the practice of journal writing, I wonder if we ever really write without an audience in mind—even if we really think we're just writing for ourselves, are we ever really unaware that others might read it?

This little trip down memory lane suggests that no writing really occurs in a vacuum. There are always external forces acting on us and influencing the choices we make as writers. With the writing tools from the last section in mind, it's appropriate now to consider the context in which writing occurs.

Suppose you’re sitting in class and the professor starts talking about a midterm essay you have to write. Or it’s near the end of the semester, you’re running low on funds, and you need to ask Mom for a little extra to help see you through. Or you’ve graduated and your boss wants you to create an informational brochure for new employees to walk them through some common tasks on the job. In each of these cases, and so many others we encounter daily, you find yourself in what we call a "rhetorical situation" where you can put writing skills to work in communicating something meaningful. That situation has become so important to scholars of writing that we've invented several ways of thinking and talking about it. One of the most common ways configures the elements of this situation as a triangle, like the one in the image below.

The Rhetorical Triangle

The Rhetorical Triangle Good writers will assess these elements before they commit themselves to written or spoken words. If you think back to other writing courses you've taken, you may have talked about something like this, even if you didn't use the same triangle metaphor. (If you took first-year writing here at BYU, you might remember using the acronym GRAPE to learn about these concepts.) The triangle we use in this text implies that these elements are interconnected and inform each other. We'll take each one in turn in the sections that follow and consider how they're connected through some examples.

2.4 Purpose

If you look at our triangle, you'll note that purpose sits squarely in the middle, surrounded by writer, audience, and message. Why do you think we situated it in the center like this? My idea is that placing purpose in the center suggests its central role in crafting the message; purpose is at the heart of the decisions we make as writers. Lots of students assume that we study writing in order to change people’s minds, and that’s certainly one of our purposes in communicating with each other. But we might also want to inform an audience, or even get them to simply feel something–although even in these cases, there’s often an implied sense that we want to change our readers’ views or feelings about something.

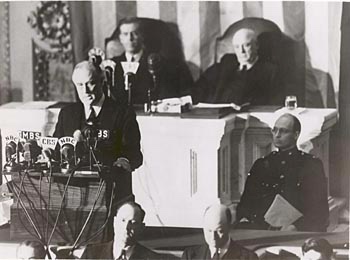

A man with a purpose: FDR delivers a speech after Pearl Harbor (Public Domain)

A man with a purpose: FDR delivers a speech after Pearl Harbor (Public Domain)Your purpose is going to shape the choices you make as a writer. If you want to report on the results of a project, you might choose to organize details in a chronological pattern since that will best convey the progress made during the project. But if you’re looking to convince investors to give you some money to develop a new mobile app, you’ll probably want to begin by talking about a common problem you see that your app can fix.

Sometimes we begin writing without really knowing what our purpose is, beyond wanting to finish the piece of writing and/or satisfy someone’s demands. That’s okay, really, and you shouldn’t always let an unclear purpose stop you from writing. Have you ever gotten two or three (or more!) pages into an assignment and there, in the last paragraph, you realize that you’ve finally discovered what you want to say? That happens to all of us, and writing is actually a powerful way for us to discover what it is we have to say about something. It’s okay if your sense of what you have to say shifts as you compose, but take advantage of opportunities to revise your work and have others read it before submitting so that you make sure your finished work has a strong sense of purpose woven throughout the piece.

Discussion Question

Think about your discipline or area of specialty within your field. What are some reasons why people in your field write or communicate? What drives people in your field to communicate?

2.5 Writer

Every message has an author behind it. When you’re interpreting or analyzing a message you receive from someone else, it’s a no-brainer to think carefully about who the author is. The author’s values and views on the world can influence the message in important ways that we want to be aware of.

But as a student in this writing class, you’re often going to be the writer, and it may seem silly to spend any time thinking about yourself in relation to your message. Nevertheless, as we’ll cover throughout this book, it’s important to consider things like your relationship to an audience and to the topic you're writing about.

Analyzing this relationship might lead you to uncover shared values or experiences that you can tap into as part of an argument. How does your audience perceive you? Considering this question can help you make choices to build your credibility with an audience so they trust what you’re communicating. Do you have implicit or unexamined biases towards the topic you're writing on? Examining these can help you approach an audience more effectively as you recognize those and acknowledge the ways they color your thinking.

2.6 Audience

Your message needs to be shaped in consideration of the audience to whom you send it. In fact, considerations of audience may be the most important forces shaping a message.

If your bank account is empty and you approach your parents for more cash, a sound knowledge of who they are and what they value will be critical to ensuring the success of your request. Do they respond better to emotionally rich requests that draw on their relationship to you or are they more compelled by logical arguments about the rising costs of college life? It’s likely you know your parents well and what will and will not work when it comes to convincing them to part with some money. The better you can come to know the audience you’re writing or speaking to in a given situation, the better you can craft your message to them.

Discussion Question

Thinking about your discipline or specialty within your field, what kinds of audiences do you imagine you will write to? How might you think about adjusting a message to one of these audiences?

Sometimes you’re going to be writing to an audience you’re unfamiliar with, and this will require you to do some imagining or some research. In the situation you’re addressing with your writing, what will your audience care about the most? What do they value that you can tap into to help change their minds? Rather than take guesses at this, many writers will try to get to know an unfamiliar audience better by speaking to them or reading things they write. Even rudimentary research can give you valuable insights into those you want to communicate with and help you select the appropriate tools and approaches in your writing.

Consider possible unintended audiences when sending out a public message. Photo by Kaboompics.com

Consider possible unintended audiences when sending out a public message. Photo by Kaboompics.comIn today’s world, it’s also true that we have to consider unintended audiences for our messages, especially when those messages are going out on a public platform like Twitter. In 2015, a woman employed in public relations sent what she thought was a humorous tweet to her 170 followers right before she boarded an international flight to Africa. While in flight, her tweet was picked up by a writer for a popular tech blog who retweeted it and posted about it on the blog; by the time this woman landed, she had received tens of thousands of tweets condemning her for what was widely perceived as a racist joke. In addition to the public humiliation she and her family faced, she was fired from her job.

Whether the public shaming this woman experienced was deserved or not, this is an important lesson in carefully considering audience–intended and unintended. The fact that our words can be shared and transmitted to other audiences suggests we need to be careful in our communications when we’re the writer, and perhaps also just a bit more humble and open-minded as listeners.

Image by Wikipedia

Image by WikipediaAnd we may have to consider computers–or at least the algorithms written for them–as part of our audience. For example, let's say you've got a message that you want to promote on a platform like YouTube or Facebook and you want it to reach a wide audience. To do so, you'll have to consider how to leverage the algorithms that promote content: How can you get your company's press release to be at the head of users' Facebook newsfeeds? Can you get your video to the front page of YouTube? Figuring this out requires understanding how those platforms make decisions about what's going to be foremost in users' feeds.

2.7 Message and Genre

For our purposes here, the message is the actual writing that we produce, whatever form it takes. One element of this message we'll pay attention to is its content. We make choices about content based on our purpose and our audience–will a personal story best move my audience or would statistics do a better job? What about a combination of the two? We might also consider the words and sentence structures that will be most appropriate–can we avoid using technical jargon, for instance, or will our audience expect that?

In addition to thinking about content, we also need to pay attention to the form our message takes. As a student, you've probably become familiar with a set of forms (or genres, which is the word we'll use more): the essay, the research report, the short essay response on an exam, etc. But in the larger world, there are a multitude of genres we could use, ranging from the opinion editorial to the press release or the political campaign speech. And new technologies are consistently bringing us new genres: Facebook and Instagram posts, tweets, text messages, and so on.

Discussion Question

Good writers carefully consider which genre will be the most appropriate for their purposes and their audience. Sometimes we don’t get a choice in this area–your boss wants a brochure for new employees or your professor assigns you a research paper. Even if we don’t have a choice, it’s still critical to understand the role that genre plays in our writing.

Scholars in the field of writing studies talk about genres as arising from social situations, and that means our writing is influenced by the context in which it takes place. Think about the wedding announcements you may have seen on Instagram or in your local newspaper and how those came to be. (You can see some from the New York Times or here's some with more local flavor from the Daily Herald.) Imagine the first couple who, way back when, decided to announce their upcoming wedding in the newspaper so it would reach a larger audience. This hypothetical first couple had to make decisions about what to include and how to phrase those details.

Through time, as these unique rhetorical situations recur, a certain set of expectations about the form the message will take begins to solidify. To return to our example, after many couples follow that first, brave couple's lead, expectations (or conventions) start to emerge, leading to the recognizable genre of the engagement announcement that we see today. Certain patterns of organization might emerge as will certain phrases that help meet the needs of the context. You know you're dealing with a formalized genre when you start to see lists with help on how to write in that genre (such as this tip sheet from Brides.com for writing up your wedding announcement in the newspaper or this one from Martha Stewart about announcing your wedding on Instagram).

An example of a longer message posted as a series of tweets (credit: @BanburyRUFC)

An example of a longer message posted as a series of tweets (credit: @BanburyRUFC)However, features that we come to expect in a genre aren’t always fixed. For instance, the tweet’s origins as a text message limited content to 140 characters, which might be enough for brief status updates (the original goal of tweets) to a group of friends, but isn't really suitable for conveying more complex ideas. But as Twitter became more widely used by corporations and governments, some of them started circumventing the 140-character limit by attaching screenshots of typed press releases. Or you may have also seen some Twitter users use bracketed numbers at the end of each tweet in a series to let you know how many individual tweets make up the larger message. The needs of people using Twitter have shaped the way it’s used and have forced the genre itself to adapt; most users can now use 280 characters in their tweets (which still isn’t a lot).

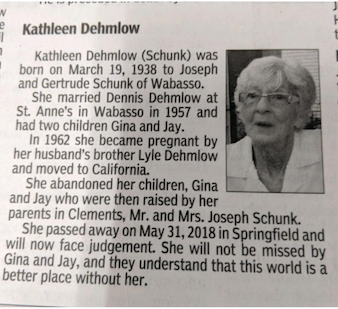

Not all forms are appropriate for every message and every situation, and a good writer will make careful choices about which genre to use in any given situation based on what each genre allows for. I’ve heard friends complain about Instagram posts with lengthy captions; these complaints suggest that most people see this platform as a way of sharing images, and they open up Instagram to see things, not to read stuff. Similarly, we don’t read obituaries expecting to learn about the deceased person’s weaknesses or failings in life; the expectations of this genre are that we extol a person’s virtues and accomplishments, even though we know that nobody’s perfect and the obituary’s subject certainly had flaws. An obituary that was brutally honest about its subject would really throw readers for a loop.

source: Minnesota Public Radio

source: Minnesota Public RadioBut even in these cases where writers may have subverted the expectations, they’re showing an awareness of the genre and how it is typically used. One obituary that went viral recently was written by siblings whose mother had abandoned them. The beginning of this obituary followed the expected conventions, but it soon takes an unexpected turn with statements like “She will not be missed by [her children]"–ouch! You might question the appropriateness of these choices (and many have, including the editors who published it), but it’s hard to deny the powerful effect of authors who understand the way a genre is supposed to work and who grab our attention by subverting it.

Discussion Question

Think about a genre you're familiar with (digital, visual, musical, or print) and consider if you've ever encountered an example of that genre that subverted or changed the expectations you have for that genre. Describe what was different about this example—just note a couple of examples—and how you reacted to it. For example, I think of the movie Shrek and how it subverted a lot of the traditional fairy tale tropes, especially in the end when the princess Fiona decides to remain an ogre. I loved that twist because, instead of following the expectation that she (like so many fairy tale heroes) would want to return to "normal," that choice celebrated Fiona recognizing something valuable and desirable in being an ogre.

The more you understand about genres (the form a message takes) and how they can be used, the more skilled you’ll be at communicating effectively. It’s important, too, to recognize that each discipline often privileges certain genres for the communication that takes place in that field. To become an expert in a field is to understand those genres and how to use them to share knowledge with other members of the field.

2.8 The Context

This idea of the context (the circle around our triangle) is kind of a catch-all for everything else that might influence our writing in a given situation. Part of this context is the social context surrounding writing that we just talked about with genre. (See how all these elements are tightly integrated?) But there are other forces to consider as well.

Something prompts the writing you do, sometimes before you even know what you want to say. For instance, after being late to class several times thanks to long lines in the campus food court, I feel like something has to change. That desire to see change might come before even knowing what change needs to take place. (The ancient Greeks would have called this desire the Exigence of the situation.)

This prompting can be external (your boss asks you to put out a press release) or it could be internal (you want to express your feelings to that special someone in a Valentine’s Day card). The compulsion might be about something really grand (there’s injustice in the criminal sentencing guidelines and you want to make others aware of that so we can make change) or something mundane (you’re going to be late to the movies so you text a friend to have them save you a seat). But the point is, some problem or need inspires us to craft some writing that we hope will address that need.

We can create a sense of urgency in our writing that not everyone might see (and that we then need to convince them of). A politician, for example, might see an emergency worthy of drastic action in the number of homeless people in a city. That sense of emergency might not be shared by others, however, who may see these numbers as not so alarming or might see other issues as more urgent. So if that politician wants to see things happen, she will need to convince her audience that the numbers of homeless people do, in fact, represent a crisis worthy of her proposed actions. Most people may not pay attention to her collection of ideas and solutions if they don't feel there's a real problem.

Good writers don’t take for granted that everyone else will see an issue or idea quite as compellingly as the writers do. Part of your job as a writer, then, may be to demonstrate the exigence of the moment that compels you to write, to persuade your audience that the time for action or change is, indeed, right now.