1. Introduction

China is a huge country both in terms of geography and population with a territory of 9.6 million km2 and a population of over 1.4 billion. It is divided into 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities directly under the Central Government, and 2 special administrative regions. Ever since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, education has always been top on the priorities of governments at all levels with no efforts spared to enhance the educational level of the whole population. Currently, China implements the policy of nine-year compulsory education (six years of primary school education and three years of junior middle school education) free of cost. Public education is the norm although private education, from K-12 to higher education, is encouraged and has made significant progress in the past few decades.

Due to historical and geographic reasons, social and economic development varies from one province to another, and even within a province, which results in disparities in educational development including educational opportunities, resources and quality. In light of this reality, addressing educational inequalities and providing equitable access to quality education for all have become a primary concern of the Central Government. Numerous measures and incentives have been taken and adopted in the continuing attempt to deliver this goal and the latest initiative which started in the turn of the century is the use of modern technology for the purpose. Digital transformation is now regarded as a national strategy for education in the 21stcentury by the Chinese Government. The emphasis that the Central Government has laid on the role of digitalization in achieving balanced development of education countrywide is echoed by the formulation and implementation of corresponding national policies, initiatives, action plans, and schemes in the past two decades. With tremendous inputs in terms of public funds and human resources as well as effective orchestration, the digitalization drive has borne fruits, especially in infrastructure and digital educational resources, and the concept of digital transformation is now ingrained in the discourse of education in general and gradually accepted by educators and other educational stakeholders.

Overall, the higher education sector is in the vanguard of this digitalization drive which has been integrated into the institutional (both long- and short-term) strategy of all colleges and universities, in particular public higher education institutions (HEIs). The most recent embodiments of the digitalization drive are the application of artificial intelligence and the emergence of 5G university campuses. As far as HEIs are concerned, digital transformation is to serve the dual purpose of responding to the national strategy and their own institutional strategy. For the former purpose, contributing to the national strategy of digital transformation of education is their social responsibility, especially for those publicly-funded HEIs. For the latter purpose, HEIs are intrinsically motivated to embark on the digitalization drive in order to improve learning, teaching, and research which can give them an advantage over other HEIs in the fierce competition both at home and abroad. A recent pertinent example is that digitally-prepared universities have managed to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic far more efficiently and effectively and to the greater satisfaction of their students than their less-digitally-prepared counterparts. In a sense, the pandemic has reinforced the embedding of digital technologies in (higher) education, an impact which will probably shape the landscape of (higher) education in the years to come.

Digitalization has positive connotations in the discourse of Chinese (higher) education, in particular the discourse in and around its education policies, although it should be admitted that there may be a gap between rhetoric (policy) and reality (practice), just as is the case in other parts of the world. It is also worth pointing out that China implements a highly centralized higher education system. Therefore, the Chinese model of digitalization may be different from those in other socio-political contexts. For example, the macro-level factors tend to play a bigger role in the digitalization drive in China, which may be very conducive to pooling limited resources and mobilizing all stakeholders for the pursuit of a common goal. This is particularly significant when China was less developed and could not provide an adequate budget for education and when it remains divided across the country in terms of educational access, quality and resources. On the other hand, the centralized mechanism may have its downsides. It is hoped that these contextual factors need to be borne in mind when reading, interpreting and even learning from this chapter.

In line with the specific research questions of EduArc, and also given the nature of chapter, the most dominant method used in this chapter is the secondary research method with the methods of case study and interview adopted mainly for the micro-level part. Data for the secondary research are government documents and institutional documents as well as materials found on official websites, including government, government department or agency, university and college, and association/partnership websites. Content analysis is made of these materials, expert opinions are sought, and discussion occurs among the project team. The researchers are insiders, hence probably with advantages and disadvantages. To avoid possible research bias, findings are often triangulated to ensure their accuracy.

This chapter aims to give an overview of digital transformation in China’s higher education sector at macro-, meso- and micro levels. The macro-level part will review national policies, standards, infrastructure construction as well as the main driving forces behind the digitalization drive. The meso-level part will cover regional and/or alliance partnerships, institutional digitalization strategies, development of (digital) (open) educational resources, and institutional infrastructure construction. The micro-level part will focus on staff and student perspectives regarding application of digital technologies in teaching, learning and administration. It is hoped that lessons learnt from China are of relevance to other parts of the world. Furthermore, comparison of different country reports may also carry rich implications for policy-makers, administrators, managers, academic staff and students, yielding fascinating new insights into digitalization of higher education.

2. Digital Transformation in the Chinese Context

Throughout the world, higher education has been undergoing digital transformation and China is no exception. The importance that the Chinese government attaches to digital transformation of (higher) education has always been consistent, as can be seen in the rest of this chapter. For example, it is stipulated in the Education Law of the People’s Republic of China (hereafter simply, The Education Law) that

The people’s government at the county level or above shall develop education via satellite television and other modern means for teaching and learning, and the administrative departments concerned shall give such development priority and support.

The State encourages the wide use of modern means in teaching and learning by schools and other institutions of education’ (Chapter VII, Article 66) (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1995).

In 2015, the Education Law was amended and new content is now added to Article 66 to the effect that the State shall promote the use of information technology (IT) in education, speed up construction of digital infrastructure and take advantage of IT to facilitate access to and sharing of high quality teaching resources and improve teaching and administration (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 2015). The Higher Education Law of the People's Republic of China (hereafter simply, The Higher Education Law), which was passed in 1998 and amended in 2015, also makes it clear in Chapter II Article 15 that ‘The State supports higher education conducted through radio, television, correspondence and other long-distance means’ (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

Sharing of educational resources is also encouraged in the Higher Education Law:

The State encourages collaboration between higher education institutions and their collaboration with research institutes, enterprises and institutions in order that they all can draw on each other’s strengths and increase the efficiency of educational resources (Chapter 1, Article 12) (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

Before we move on to other sections, it would be desirable to clarify terminology used in this chapter. First, in the Chinese context, informatization is the ‘standard’ term for the use of IT while digitalization is more often used to refer to the use of a specific technology, i.e. digital technology, rather than as an umbrella term. But given the background of the audience of this report, we will use digitalization rather than informatization as an umbrella term. Second, there is no official definition of Open Educational Resources (OER) in China. Judging from our knowledge of this field, it seems that Chinese policy makers, researchers, and practitioners follow ‘by default’ the definition of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), according to which OERs are

teaching, learning and research materials in any medium, digital or otherwise, that reside in the public domain or have been released under an open license that permits no-cost access, use, adaptation and redistribution by others with no or limited restrictions (UNESCO, 2012).

3. Digital Transformation of the Chinese Higher Education System

3.1 Facts and figures

According to the Higher Education Law,

The State Council shall provide unified guidance and administration for higher education throughout the country.

The people’s governments of provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the Central Government shall undertake overall coordination of higher education in their own administrative regions and administer the higher education institutions that mainly train local people and the higher education institutions that they are authorized by the State Council to administer (Chapter 1, Article 13) (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

The establishment of undergraduate or post-graduate HEIs is subject to review and approval by the Ministry of Education (MOE) under the State Council and the establishment of junior colleges whose graduates are not degree holders is subject to review and approval by the people’s governments of provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the Central Government but needs to be reported to the State Council.

The Higher Education Law also ensures funding for public HEIs and encourages non-State sectors to be involved in the provision of higher education (see Chapter VII ‘Input to Higher Education and Guarantee of Conditions’ for details):

The State institutes a system wherein government appropriations constitute the bulk of the funds for higher education, to be supplemented by funds raised through various avenues, so as to ensure that the development of higher education is suited to the level of economic and social development.

The State Council and the people’s governments of provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities directly under the Central Government shall, in accordance with the provisions in Article 55 of the Education Law, ensure that funds for State-run higher education institutions gradually increase.

The State encourages enterprises, institutions, public organizations or groups and individuals to invest in higher education (Article 60) (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998).

Implied in Article 60 of the Higher Education Law are two messages. One is that there are both public and private colleges and universities in China and the other is that public HEIs are the most dominant force in China’s higher education sector. With the rapid growth of economy in the past four decades, the Chinese Government’s investment in education has been on the rise all the time, including higher education. Therefore, unlike their foreign counterparts, Chinese HEIs, especially public colleges and universities are financially more secure and stable, even in recent years of global economic austerity which has had a significant impact on colleges and universities around the world (Qayyum & Zawacki-Richter, 2018; Zawacki-Richter & Qayyum, 2019).

Up to May 31st, 2017, there were 2914 HEIs in China[1], including 2631 conventional campus-based HEIs and 283 adult HEIs (see the list of Chinese colleges and universities for details) (MOE, 2017a). Of all these HEIs, 75 are affiliated to the Chinese Ministry of Education, about 30 to other ministries and the rest of them to the provincial governments or their education authorities where they are located, hence often referred to as ‘local colleges and universities’. It should also be noted that there are 747 private HEIs with an enrolment of 6,284,600, representing about 17% of the total higher education student population in China. The latest statistics show that China has a higher education student population of 37,790,000, reaching a gross enrolment ratio of 45.7% in higher education (MOE, 2018a).

3.2 Current state of overall digital transformation

In 1998, MOE announced its Action Plan for Invigorating Education towards the 21st Century (hereafter simply, the Action Plan), which called for the implementation of Modern Distance Education Initiative to build an open education network and establish a lifelong learning system in China (MOE, 1999a). It was argued that Modern Distance Education Initiative should make good use of a variety of educational resources and contribute effectively to equal access to educational resources, which was of significant relevance to China where there was still a shortage and uneven distribution of educational resources (MOE, 1999a). Measures to build or improve technology infrastructure for the implementation of this initiative were outlined in this official document (MOE, 1999a). In 1999, the State Council published its Decision to Deepen Educational Reform and Fully Promote Quality-oriented Education (hereafter simply, the Decision), Article 15 of which clearly voices the Chinese government’s strong support to the enhancement of the use of educational technology and digitalization of education in addition to the establishment of a modern distance education network (State Council, 1999). As pointed out above, digital transformation can trace its root to the Education Law. Nevertheless, we may be justified in arguing that what started digital transformation materializing were MOE’s Action Plan and the State Council’s Decision.

In 2003, as one of the measures to implement strategies and decisions from the Central Government and its education authorities to modernize education in China, MOE launched an initiative to develop ‘Top-quality Courses’, encouraging HEIs around the country to be actively engaged in this project by developing and submitting their courses for review with the aims to effectively promote innovation in education, deepen teaching reform, facilitate the use of modern IT in teaching, and share high quality teaching resources. MOE pledged to subsidize the project and organize reviews of these courses. Courses which received high ratings by a panel would be awarded the title of ‘State-benchmarking Course’ and be curated on a website exclusively for the purpose of sharing these courses (http://www.jingpinke.com) (MOE, 2003)[2]. From 2003-2010, nearly 4,000 courses were recognized as ‘State-benchmarking Course’ (Hu, Yang, Wei & Yang, 2014; Wang & Håklev, 2012).

In the same year, China Open Resources for Education (CORE) was established following the MIT OpenCourseWare conference in Beijing. CORE was a non-profit organization,

a consortium of universities that began with 26 IET Educational Foundation member universities and 44 China Radio and TV Universities, with a total enrollment of 5 million students. It aimed to provide Chinese universities with free and easy access to global open educational resources and provides the framework for Chinese-speaking universities to participate in the shared, global network of advanced courseware with MIT and other leading universities (China Open Resources for Education, n. d.).

Ever since these early initiatives, digitalization has been gaining increasing momentum with more and more national policies made and introduced with the aim to encourage and speed up digital transformation in China’s (higher) education sector, as is evident in the following sections of this report. Governments at all levels have invested heavily in digitalization infrastructure and capacity building for this purpose. In 2016, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang advocated the integration of the idea of Internet Plus into every sector of the society, including education, in his report to the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China on behalf of the Central Government, which can be regarded as the culmination of the Government’s emphasis on digitalization in the past decades and has ever since sparked greater enthusiasm for digital transformation in the whole society.

To provide a snapshot of the current state of digital transformation within higher education in China, a preliminary analysis was conducted of the 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans of 75 universities which are directly under MOE[3] (MOE, n. d.). Of the 75 universities, 56 mention their achievements in terms of digitalization in the 12th Five-Year period (2011-2015); 48 outline their digitalization strategies for the 13th Five-Year period; and all of them delineate specific digitalization transformation measures in terms of instruction, learner support, administration and management as well as the university’s for-profit businesses (see Section 5.2 for details). It may be unrealistic to predict how well the goals and objectives set in these five-year development plans will be delivered at the end of the 13th Five-Year period. Nevertheless, what these development plans display is really a promising vision for digital transformation in the Chinese higher education sector in the foreseeable future.

4. Digital Transformation at the Macro Level

4.1 OER Policy-making

As mentioned earlier, MOE’s Action Plan (MOE, 1999a) and the State Council’s Decision (State Council, 1999) initiated the digital transformation movement in the (higher) education sector. But it was not until in the last decade that policies were formulated and introduced one after another in an attempt to boost the digital transformation process and maximize the benefits that it has brought forth.

In 2010, Outline of China’s National Plan for Medium and Long-term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020) (hereafter simply, the Outline) was published (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China & State Council, 2010), Chapter 19 of which is dedicated to acceleration of digital transformation, including speeding up infrastructure construction, developing and using high quality educational resources on a greater scale, and building a national education information management system.

In order to implement the Outline, MOE formulated its Ten-Year Development Plan for Educational Digitalization (2011-2020) (hereafter simply, the Ten-Year Development Plan) (MOE, 2012a), which delineates the overall strategy (including current state and challenges, principles and guidelines, and development goals), development targets (including narrowing digital divide, sharing high quality educational resources, accelerating digitalization in vocational education, promoting integration of IT and higher education, improving the lifelong learning system, enhancing education management efficiency, upgrading public service capacity, strengthening professional development, and ensuring sustainability), action plans, and guarantee measures.

In 2015, the State Council issued its guidelines on promoting the idea of Internet Plus in all walks of like (State Council, 2015), which advocates the establishment of an innovative mode of education provision. Internet enterprises and educational institutions are encouraged to collaborate in developing digital educational resources and providing online education to meet market demands; schools are urged to make full use of digital educational resources and online education platforms, experimenting with new models of online education, widening access to high quality educational resources and contributing to educational justice. The guidelines also recommend sharing of online course materials in the provision of degree/diploma programs, offering more Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), exploring mechanisms for recognition and transfer of online learning credits, and accelerating transformation of higher education business models (State Council, 2015). In the same year, MOE called for HEIs to develop and use MOOCs more extensively and effectively (MOE, 2015a) and issued its guidelines on comprehensively promoting digital transformation in education in the 13th Five-Year period, for example, adopting and localizing MOOCs and Clipped Classroom practice as well as innovating instructional management in HEIs (MOE, 2015b).

In 2016, MOE issued its 13th Five-Year Plan for Educational Digitalization (hereafter simply, MOE’s 13th Five-Year Plan) (MOE, 2016), the main goal of which was to better implement the Outline published by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council (2010) and the Ten-Year Development Plan (MOE, 2012a), with the overarching aim to advocate such development ideas as innovation, coordination, green, open and sharing in order to establish an online, digital, personalized and lifelong education system and build a learning society where anyone can learn anywhere and anytime. When it comes to HEIs, it urges colleges and universities to continue to develop and open up their online courses to the general public and encourages HEIs affiliated to MOE and other ministries to help HEIs in West China to carry out blended instruction reforms by taking advantage of open online courses. The Central Government promises to support and push forward HEIs’ ongoing efforts to share digital educational resources, encouraging them to establish online education alliances and university-enterprise alliances for continuing education in order that HEIs’ high quality educational resources can be put to better use (MOE, 2016).

In January, 2017, the State Council published The 13th Five-Year Plan for National Educational Development (hereafter simply, the National 13th Five-Year Plan) (State Council, 2017), which outlines China’s major objectives and targets for the education sector at the national level over the period 2016-2020. There are 38 mentions of the term ‘educational resources’ in this document which has a length of about 42,000 Chinese characters. There is a subsection on developing ‘Internet Plus’ education which covers four areas: accelerating the development of a sound system of rules and regulations, further improving infrastructure conditions, committedly pushing forward in-depth integration of IT and education, and continuing to promote co-construction and sharing of high quality educational resources. In terms of rule-and-regulation setting, it highlights the need to formulate standards for the quality of online education and digital educational resources, develop approval and monitoring mechanisms for digital educational resources, protect authors’ intellectual property rights and encourage the business sector and other non-government sectors to develop digital educational resources, contributing to the emergence of a market conducive to the growth of digital educational resources. In terms of infrastructure, it aims to achieve full coverage of broadband networks and popularization of online instruction environments. Another focal point of infrastructure construction is to continue the construction of a national public platform for educational resources as well as a platform for educational administration and management. In terms of integration of IT and education, teachers are encouraged to make use of IT to enhance their instruction, innovate new instructional methods, and benefit from high quality educational resources by practicing new methods such as Flipped Classroom and blended instruction. Finally, this official document also calls for HEIs to develop open online courses that are in line with their respective expertise, set down instructional quality evaluation criteria and credit recognition rules for open online courses, as well as incorporate online courses into the curriculum and syllabus. Co-construction of educational resources and platforms for OER is also encouraged.

In 2018, MOE issued its Action Plan for Educational Digitalization 2.0 (hereafter simply, Educational Digitalization 2.0) (MOE, 2018b). Educational Digitalization 2.0 sits under the Outline (Central Committee of the Communist Party of China & State Council, 2010), MOE’s Ten-Year Development Plan (MOE, 2012a), its 13th Five-Year Plan (MOE, 2016) and the National 13th Five-Year Plan (State Council, 2017). The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), which was held between 18 and 24 October, 2017, set new goals for all sectors of China, including (higher) education. Educational Digitalization 2.0 can be regarded as an updated version of previous digitalization plans in order to better respond to the spirit of the 19th CPC National Congress.

The fundamental intention of Educational Digitalization 2.0 is that by 2022 all teachers will teach via digital means; all students will learn via digital means; all schools will have digital campuses; digitalization application and digital literacy of teachers and students will reach a higher level; and an ‘Internet Plus’ education platform will be built (MOE, 2018b). Of particular relevance to HEIs are the improvement of MOOC provision and the collaboration of HEIs and other social sectors in providing top quality MOOCs. 3,000 State-benchmarking Open Online Courses, 7,000 national-level and 10,000 provincial-level higher education top quality courses, both online and offline, will be developed as ‘model courses’ setting examples of how IT can be integrated into education. Guidelines on digital campus construction for schools at all levels, including HEIs, will be formulated and put into use. Capacity building for teachers, including HEI teachers, is also placed on the agenda. Compared with earlier digitalization plans, Educational Digitalization 2.0 is characterized by application of cutting-edge technologies such as AI, big data, blockchain technology, and smart devices. Digital transformation is one of the 10 strategic priorities of China’s Education Modernization 2035 Initiative and one of the 10 key development tasks of the corresponding Five-year Implementation Plan for Speeding up Education Modernization (2018-2022), both recently issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council (2019 a, 2019 b).

Higher education in China is a highly centralized system although according to the Education Law (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 2015) and the Higher Education Law (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998) the Central Government delegates some administration and management responsibilities of HEIs to provincial governments. Given the Chinese social system and this centralized feature of (higher) education, the broader policy environment plays a key role in influencing the digital transformation of the country’s higher education. An in-depth analysis of the above favorable government policies show that digital transformation in the (higher) education sector has always been considered as some kind of national strategy. Hence, funding and human resources can be guaranteed and relevant barriers can be cleared away more effectively. For example, the last section of MOE’s Educational Digitalization 2.0 describes five measures to ensure the successful implementation of this plan (MOE, 2018). The first measure is to strengthen leadership and coordination. China is a geographically vast country with radical differences in different regions, hence the urgent need for strong leadership and coordination. Educational digitalization is listed as an evaluation index of local educational development. The second measure is to innovate new ways of investment in educational digitalization, diversifying sources of financial input. The third measure is to pilot educational digitalization on a small scale and use lessons learnt from these pilot projects to train teachers, managers and administrators. MOE also urges local authorities to create a favorable atmosphere for this transformation and change educators’ traditional mindset using both traditional and new media. The fourth measure is to continue cooperation with international organizations and institutions such as UNESCO and to be actively involved in international initiatives of educational digitalization, exchanging experience with international counterparts and learning from each other. The last measure is to assume accountability for the security of cyber space. Chief administrators of educational institutions are held accountable for cyber security and appropriate mechanisms are to be put in place. It is of paramount importance that the Central Government pledges its support to digital transformation. Otherwise, educational institutions would have to struggle to move on with a less promising vision ahead.

4.2 Association and national standards

In 1999, MOE decided to establish the Modern Distance Education Resources Committee (MDERC) and its Expert Panel with the aim to drive the construction of modern distance education resources and assure their quality (MOE, 1999b). The tasks set for this committee included formulating principles and policies for developing modern distance education resources, making resource development plans, coordinating the construction of all kinds of educational resources at all levels, and formulating technological standards.

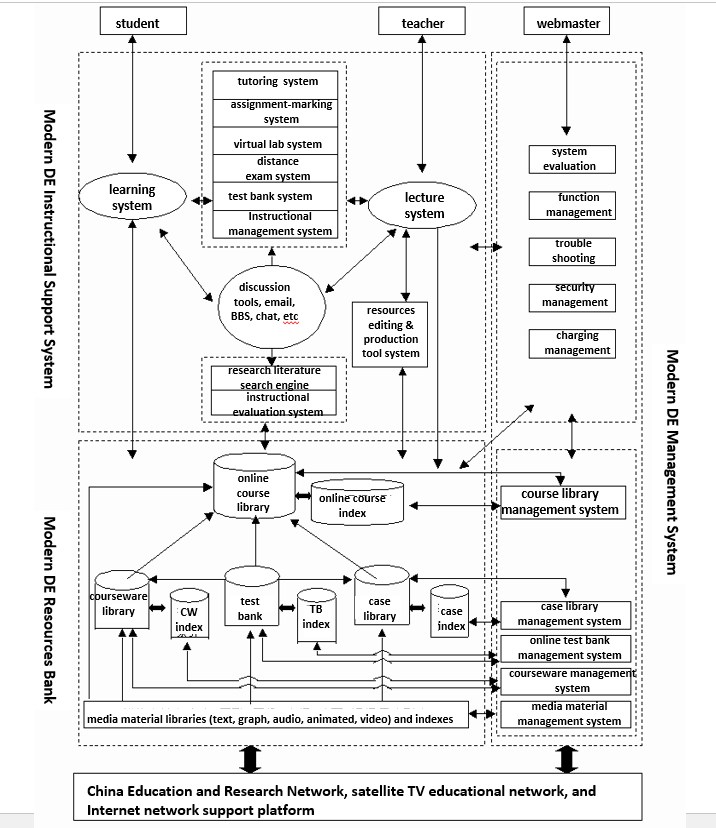

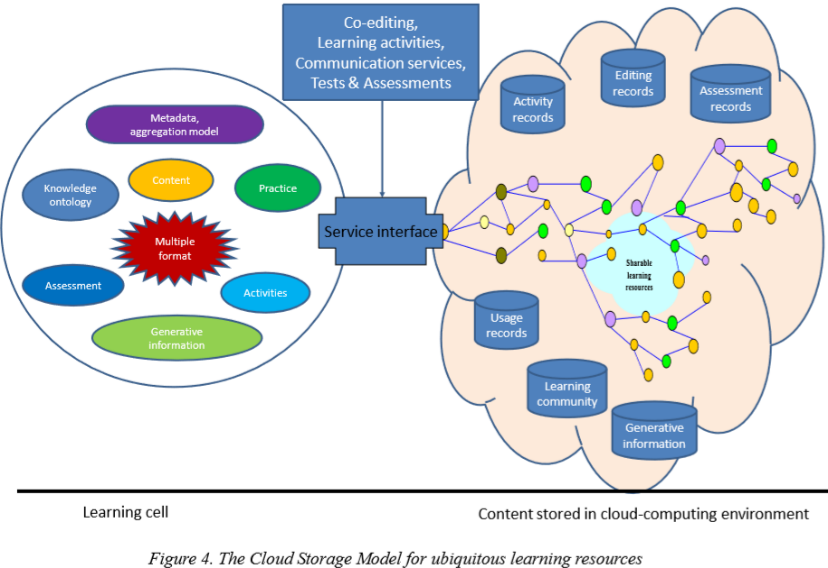

Figure 1

Modern Distance Education Resources Construction Architecture (MDERC, 2000).

In May, 2000, MDERC issued Technical Specifications for Modern Distance Education Resources Construction (TSMDERC) (trial version) (MDERC, 2000). As is clearly stated in the Preface, this standard focuses on the guidelines for resource developers, production requirements, and functions of the management system, rather than on the data structure of the software system. Parts of the specifications draw on Learning Object Metadata (LOM) model by IEEE LTSC (Learning Technology Standards Committee). Educational resources as referred to in this document include media material library, test bank, case library, courseware library and online courses. Its educational resources development architecture covers an instructional support system and a management system (see Figure 1).

But TSMDERC is not mandatory. Nor is it a national standard in the proper sense of the term. Rather, it is an association standard. MOE’s Educational Digitalization Technology Standard Committee (EDTSC) came up with a draft version of Technical Specifications for Educational Resource Construction Information Model CELTS-41.1 CD1.0 in December, 2002, which drew on TSMDERC as well as LOM by IEEE LTSC but never went official (EDTSC, 2002; Q. Li, personal communication, January 3, 2019).

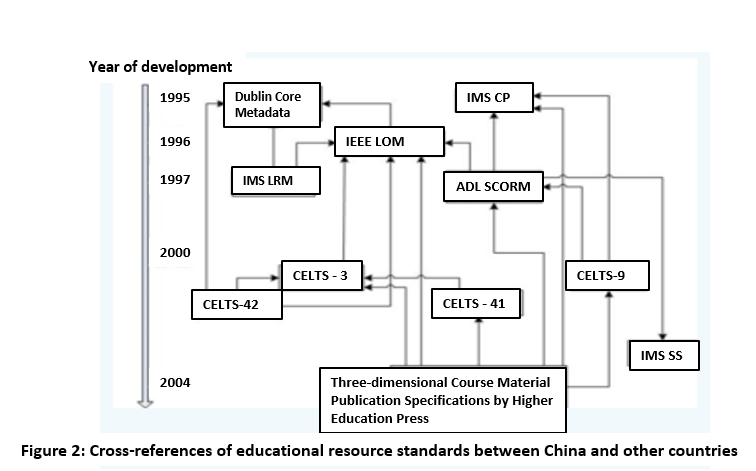

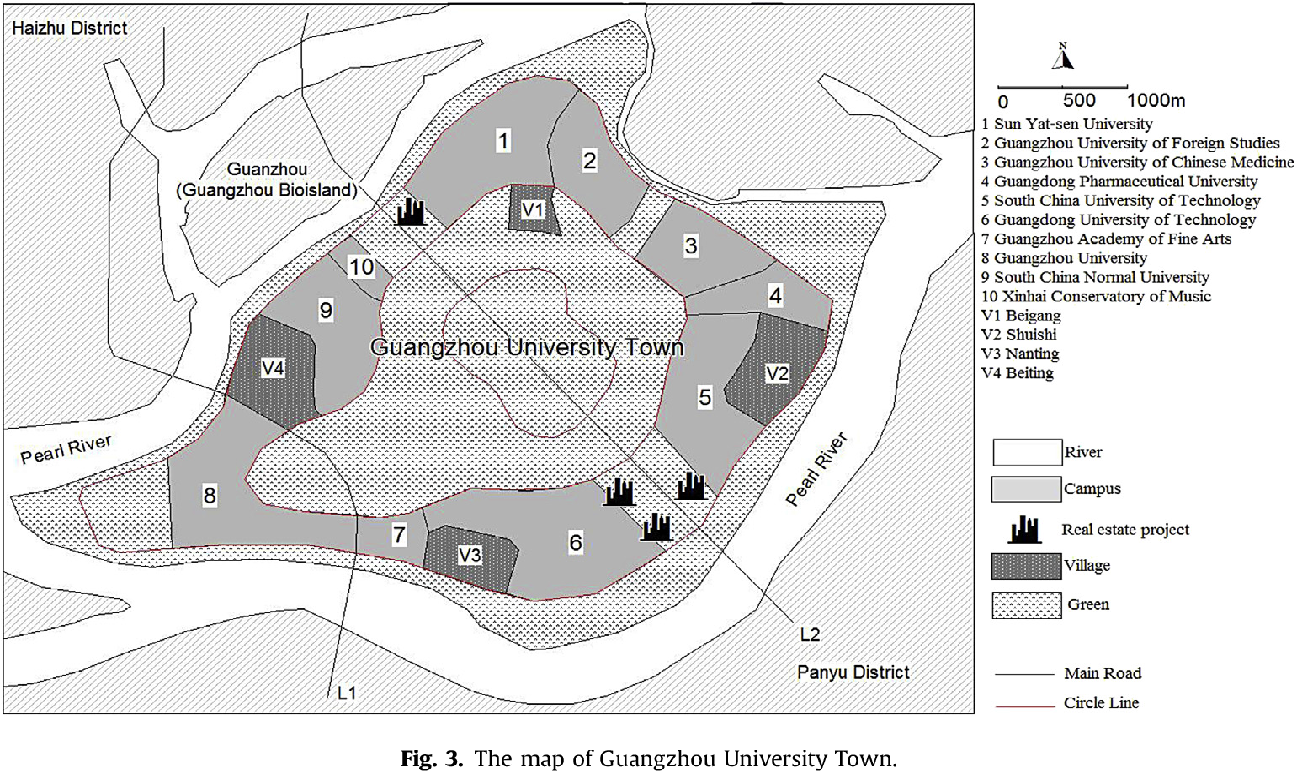

Similar to TSMDERC is Technical Specifications for State-benchmarking Shared Courses Construction (TSSSCC) issued by MOE (2012b). Educational resources as referred to in TSSSCC include basic resources (course profile, syllabus, calendar, lesson plan or presentation slide, key content, assignment, reading list and video lecture) and extended resources (for example, case library, assorted lecture library, multiple-media resources library, discipline-specific knowledge retrieval system, demonstration/virtual/simulation training system, test bank system, assignment system, online self-testing or online examination system, tools for learning, teaching and discussion, as well as online courses based on multiple media). In terms of basic resources, TSSSCC covers the structure, format and technical specifications, and metadata specifications of a basic resource. For example, the metadata of a resource should include Title, Author, AuthorOrg, Copyright, Level, Readers, Subject01, Subject02, ResourceType, MediaType, Keywords, Abstract, CourseTitle, Language and Note (MOE, 2012b). As for extended resources, TSSSCC also creates some technical requirements. The relationship between these association standards and international e-learning standards and specifications is demonstrated in Figure 2 (Lu & Wei, 2005).

Figure 2

Cross-references of educational resource standards between China and other countries

(Note: CELTS-3 Learning Object Metadata (LOM) Specifications; CELTS-9 Content Packing Specifications; CELTS-41 Technical Specifications for Educational Resource Construction; CELTS-41 Metadata Application Specifications for K-12 Educational Resource)

In addition to these association standards, there are also national standards in relation to educational digitalization in China. Chinese E-Learning Technology Standardization Committee (CELTSC) has developed dozens of national standards ranging from general guidelines to learning resource, learner, learning environment, education management information, multimedia instruction environment, virtual experiment, learning tool as well as e-textbook and e-schoolbag.[4] Standards concerning learning resources include

- GB/T 36347-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Common cartridge profile for learning resources

- GB/T 36350-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Semantic description of digital learning resources

- GB/T 28825-2012 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Classification and codes of learning resource

- GB/T 29807-2013 Information technology - Learning, education and training -XML binding specification for learning object metadata

- GB/T 29809-2013 Information technology - Learning, education and training -Content packaging XML binding

- GB/T 29802-2013 Information technology - Learning, education and training - An information model for test and question

- GB/T 30265-2013 Information technology - Learning, education and training -Learning design information model

- GB/T 29810-2013 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Test and question information model XML binding specification

- GB/T 26222-2010 Information technology - Learning, education and training -Content packaging

- GB/T 36437-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Simple sequencing of courses

- GB/T 21365-2008 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Learning object metadata

- GB/T 36642-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training -Online courses[5]

These national standards were developed by researchers from universities, research institutes and/or the corporate sector under the leadership and coordination of CELTSC. For example, GB/T 36642-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Online courses was the result of joint efforts by 39 researchers from six universities (Tsinghua University, East Chia Normal University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Beijing Normal University, Capital Normal University and Shenzhen University), China Electronics Standardization Institute, and four enterprises. The leading researcher, Professor Li Zheng from Tsinghua University, explained the purpose of this standard in an interview which we believe is applicable to all the above standards (Xin, 2018). According to Professor Zheng, on the one hand, the implementation of GB/T 36642-2018 can break down technical barriers between different platforms and different educational institutions in terms of educational resource sharing; on the other hand, technical standardization is conducive to equal access to education. Moreover, this standard can also facilitate cross-platform comparison and evaluation of online courses and define the basic support functions of an online course platform. In other words, these standards are designed to facilitate development and sharing of digital educational resources so as to optimize their use, reducing repetitive investments and increasing cost-effectiveness.

Like the above mentioned association standards, these national standards are not mandatory either. Therefore, the development of standards can benefit from the involvement of the corporate sector which is a major driving force behind the application of standards in practice, according to Zheng (Xin, 2018). For example, Beijing Muhua Information Technology Co., LTD., which develops and operates the Tsinghua University-funded Xuetangx.com, ‘the world’s first Chinese MOOC platform, authorized to operate edX courses in the Chinese mainland’[6], is a partner institution of GB/T 36642-2018 Information technology - Learning, education and training - Online courses. The other corporate co-developers of this standard are MOE’s Higher Education Press, IFLYTEK Co., LTD (iFLYTEK) (a software enterprise) and UOOC.ONLINE. Beijing Muhua Information Technology Co., LTD has committed to taking the lead in applying this standard to online courses offered at Xuetangx.com.

Up to December, 2018, CELTSC has developed 46 national standards and 12 association standards on educational digitalization (Xin, 2018).

4.3 Driving forces behind digital transformation

Digital transformation at the macro level is driven by the determination of the Central Government to modernize Chinese education, enhance (higher) educational quality, and achieve educational equality by investing in digital infrastructure construction, capacity building, technology-enhanced learning and teaching, and developing and sharing of high quality educational resources. It is a national strategic mission. The determination of the State to pursue educational digitalization has remained steadfast in the past decades, as is evidenced by the Education Law (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1995) and the Higher Education Law (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998) as well as numerous national strategic plans, including several which were dedicated to educational digitalization (see Current state of overall digital transformation under the Digital Transformation of the Chinese Higher Education System section and Policy-making under the Digital Transformation at the Macro Level section).

To deliver the goals of educational digitalization, measures were taken by the Central Government and MOE to ensure the successful implementation of relevant policies, including providing funding, incentive or subsidy, strengthening leadership and coordination, creating a favorable innovative atmosphere, and promoting international cooperation (see MOE, 1999a; MOE, 2012a; MOE, 2018). For example, in 2011, MOE issued a series of suggestions on the development of State-benchmarking Open Courses, which included awarding of honorable titles and provision of funding in the form of subsidy to courses which were well received after being made available online (MOE, 2011). A similar measure was taken by MOE in 2012 to encourage the construction of State-benchmarking Shared Courses (MOE, 2012c).

From 2012 to 2016, eight reviews were conducted of video open courses and altogether 922 resources were awarded the titled of Top-quality Video Open Course with financial support given to the providing universities.[7] From 2013 to 2016, MOE approved 2911 projects on development of State-benchmarking Shared Courses, each of which was granted a subsidy of RMB 100,000 yuan as development fee.[8]Of these courses, 2866 were awarded the title of State-benchmarking Shared Course in 2016[9]and 2017[10] respectively. In 2017 and 2018, MOE awarded 1291 online courses the title of State-benchmarking Open Online Course.[11]

MOE is pushing forward the recognition of MOOC credits, according to the head of the Higher Education Section of MOE (Wu, 2018). So far, over 6 million higher education students have obtained credits by learning MOOCs. MOOCs are believed to be able to break the boundary of traditional education and tear down the walls of brick-and-mortar educational institutions, hence disrupting campus-based classroom teaching and transforming education in a radical manner. Intensive integration of IT and education can afford Chinese HEIs great opportunities to overtake their counterparts in advanced countries (Wu, 2018). This is a very strong motivating force behind the State’s strategy of educational digitalization. China has reiterated, again and again, the determination to carry out digital transformation in its (higher) education sector.

4.4 OER Infrastructure: National platforms

In 1994, funded by the Central Government and directly under the supervision of MOE, six elite universities in China ‘set up the first education network using transmission control protocol/Internet protocol “China Education and Research Network” (CERNET)’ (Zhao & Jiang, 2010, p. 574). CERNET is now accessible all over China with universities and colleges, primary and secondary schools and research institutes as its users, ensuring ‘safe and high-speed information exchange among educational institutions both at home and abroad’ and ushering in the era of e-campus to Chinese HEIs (Zhao & Jiang, 2010, p. 575). Given its role, CERNET may well be regarded as the meta-infrastructure of digital transformation for Chinese HEIs.

Openness and sharing have been advocated and practiced ever since the initial stage of educational digitalization in China. For example, when MOE initiated a project to develop high quality course resources in 2003 (MOE, 2003), courses which had been awarded the title of ‘State-benchmarking Course’ were curated on a website exclusively for the purpose (http://www.jingpinke.com), freely available to the general public for five years (Wang & Håklev, 2012). This platform, operated by Higher Education Electronic Audio-Video Press affiliated to MOE, has been restructured and becomes a repository of educational resources both at the undergraduate and junior college/vocational higher education levels, storing a total of 1,299,268 resources in a variety of subjects, including history, management, education, science, engineering, medical science, bio-chemistry, pharmacy, civil engineering, electronic information, textile, food, health care, tourism, arts, design and media.[12]It also puts a comprehensive incentive scheme in place to encourage users to share resources.[13]

In 2011, MOE launched another initiative to develop top quality open courses, with more emphasis on the use of information and communication technology (ICT). Open courses are comprised of two types: top quality video open courses and top quality shared courses. Up to January 3rd, 2019, 992 video open courses and 2884 shared courses are curated on iCourse platform, operated by Higher Education Press affiliated to MOE, which is also home to MOOCs provided by Chinese universities and establishes a space called ‘School Cloud’ to offer customized service to partner HEIs in relation to the development, management and application of open online courses.

In 2012, the National E-learning Resources Center (NERC) was established and is operated by the Open University of China (OUC) (formerly known as China Central Radio and Television University [RTVU], China’s only dedicated distance education institution at the national level governing a national network of RTVUs). Like its developer and operator OUC, NERC has established a national network. So far, NERC has set up 255 branches nationwide with 51,000 courses available. NERC was a deliverable of the HEI undergraduate teaching quality and teaching reform project (MOE & MOF, 2007). One of its sub-projects was the Construction of Online Education Digital Learning Resources Center, undertaken by OUC in 2008. It took OUC five years to construct NERC.

In 2014, NetEase, an Internet technology company and MOE’s Higher Education Press started an online education platform - Chinese University MOOC (CUM), curating State-benchmarking Open Courses and providing MOOCs developed by Chinese universities. This is a very popular MOOC platform in China with relatively more information available online. Therefore, the rest of this section will focus on describing CUM.

Like other large MOOC platforms in China, CUM is a centralized platform. Its course development guidelines cover course development specifications and requirements as well as instructions on operating the platform (iCourse Center, 2014). Part I Specifications and Requirements is subdivided into teaching content and course structure. Specifications are laid down on teaching content in terms of video lecture production (length, resolution, format and size, audio quality, image layout, subtitle, and interaction design), teaching materials (types and format), quiz (self-assessment and auto marking), discussion, unit test and assignment, and examination as well as on course structure in terms of duration, two levels of heading and corresponding content, and modes of content delivery. According to the latest statistics (National HEI Teaching Research Center & iCourse Center, 2018), up to December 31st, 2017, CUM provided nearly 2,000 MOOCs, including MOOCs labeled as Chinese University MOOCs (that is, using its own brand name), Chinese Advanced Placement (CAP) MOOCs, vocational education MOOCs, and general open online courses, with engineering, science, life science, economics and management, and computing topping the list of the most popular subjects. Over 10 million learners registered with CUM, with an average enrollment of four MOOCs per person (40,370,000 course enrolments by December 31st, 2017). MOE awarded 490 MOOCs as State-benchmarking Open Online Course for the first time in 2017 (MOE, 2017b) with 65.7% of them (322 MOOCs) from CUM. It is worth mentioning that CUM also offers space for Small Private Online Courses (SPOCs) for partner HEI students. Unfortunately, many OER platforms do not have in place specific evaluation mechanisms for educational resources uploaded, hence failing to assure their quality and compromising users’ experience (Dong, Du, Xu, Zheng, & Hu, 2017).

Although CUM is a joint venture by NetEase from the corporate sector and MOE’s Higher Education Press, it is non-profit in nature. As a centralized platform, providers of MOOCs need to design and develop their course resources in accordance with CUM’s guidelines (iCourse Center, 2014) and upload all the resources to the platform. All the learning activities, assessments and learner support go on through the platform. Learners who have managed to complete and pass a course will be issued an electronic certificate of accomplishment free of charge but can pay to obtain a paper certificate if they so wish (Y. Han, personal communication, January 3, 2019; Hu, Yu & Chen, 2015).

5. Digital Transformation at the Meso Level

5.1 Alliance and subject-based partnerships

Legal and policy foundations

As mentioned above, China is a geographically vast country with blaring disparities in different parts in terms of economic and social developments, including distribution of educational resources. In the light of this reality, cooperation between HEIs and cooperation between HEIs and research institutes, the business sectors and/or other institutions are encouraged in the Higher Education Law so that parties concerned can give full play to their respective advantages and put educational resources to more effective use (The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China, 1998). Chinese HEIs’ awareness of the necessity and benefits of joint development and sharing of educational resources can be traced back to 2003 when they formed CORE to coordinate cooperation in developing open educational resources between HEIs, both at home and abroad.

Given that an effective mechanism to boost co-development and sharing of high quality digital educational resources has yet be to established, as pointed out in the Ten-Year Development Plan (MOE, 2012a), one of the principles and guidelines proposed by MOE in this document is application-driven joint development and sharing of high quality digital educational resources. To achieve this objective, MOE stresses the need to establish an open cooperation mechanism to facilitate government-led, multi-party-involved joint development and sharing (MOE, 2012a). Cooperation in developing sharable digital educational resources is a recurrent theme in this plan. For example, it highlights the importance of joint development and sharing of high quality digital educational resources, comprehensive in-depth integration of IT and education, and promotion of innovations in instruction and administration to ensure educational justice, enhance educational quality and build a learning society. To this end, MOE aims to push forward the formulation of technical specifications and application guidelines for digital educational resources and to develop corresponding review and evaluation index systems (MOE, 2012a). Of particular relevance to the higher education sector are (1) to establish a mechanism for co-developing and sharing higher education resources in order that HEIs can benefit from each other’s high quality courses and library resources as well as digital laboratory platforms in instructional practice; (2) to encourage the co-development and sharing of high quality instructional and research resources between East China and West China HEIs; and (3) to support students’ inter-institutional selection of online courses and the joint development of these courses (MOE, 2012a).

Cooperation in developing and sharing digital educational resources is also emphasized in MOE’s 13th Five-Year Plan (MOE, 2016a), which calls for the establishment of online education alliances and university-enterprise alliances for this purpose. In the same year (2016), MOE announced its Action Scheme for Joint Development of Education in the One Belt and One Road Countries (MOE, 2016b). Cooperation in educational resource development and sharing is one of the recurrent themes in this scheme.

Co-construction of educational resources and platforms for OER is also encouraged in the National 13th Five-Year Plan (State Council, 2017), which points out that co-development and sharing of high quality educational resources can accelerate transformation in educational provision models and learning styles.

In 2018, MOE announced its Educational Digitalization 2.0 (MOE, 2018b), with the establishment of an integrated ‘Internet Plus Education’ mega-platform as one of its key goals. This mega-platform is intended to integrate public educational resource platforms and support systems of various sorts and at various levels with the aim of building a public system of national digital educational resources. One of the proposed actions is cooperation between HEIs and other social sectors in developing top quality MOOCs (MOE, 2018b).

A preliminary analysis of the 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans of 75 universities which are directly under MOE (MOE, n. d.) also shows that some HEIs realize the value-added benefits of cooperation with their counterparts in developing and sharing (digital) educational resources, especially MOOCs and other online course materials.

Given such steadfast policy support in the broader social and political context, it is no surprise that the number of partnerships in this field has mushroomed, in particular in the most recent years. Nevertheless, despite consistent support from the Central Government, cooperation in this field needs strengthening. HEIs, professional associations, and the business sector should be more actively involved in joint development of educational resources and corresponding resource-sharing platforms (Dong, et al., 2017). In other words, a more effective mechanism is needed to ensure the sustainability of these joint efforts, according to Dong et al. (2017). Cooperation in educational resource development and sharing is also influenced by relevant factors. For example, in terms of policy support, recognition and transfer of credits acquired from learning open or sharable educational resources, appraisal of the quality of these educational resources, accreditation of the operation of their platforms, and protection of copyrights, among other things, should be institutionalized (Hu, et al., 2015).

Examples of regional and/or alliance partnerships

CNMOOC is the official website of Top Chinese University MOOCs Alliance , launched by Shanghai Jiao Tong University in April, 2014, originally aiming to promote mutual recognition of MOOC credits among the 19 HEIs in southwest district of Shanghai and to enable students to study a second degree in the partner universities (Wu, 2015). CNMOOC is an open, non-profit, cooperative educational platform, serving not only the partner institutions but also the general public.[15] It now has 101 partner institutions, including 92 universities and nine other institutions (CNMOOC, n. d.). Up to January 13, 2019, in addition to a micro specialization, it has 957 courses offered on the platform, taught in Chinese (842 courses) and English (115 courses), in the subject areas of philosophy, economics, law, education, literature, history, natural science, engineering, agriculture, medicine, military science, management science, and arts.[16]

University Open Online Courses (UOOC)

UOOC, launched by Shenzhen University in South China, is the website of the UOOC Alliance of Local Universities. As mentioned earlier, of the nearly 3,000 colleges and universities in China, except the 75 universities affiliated to MOE and about 30 others affiliated to other ministries of the Central Government, the rest of these HEIs are often referred to as ‘local universities’. UOOC is the first alliance of local universities in China, guided by the principles of joint creation, joint construction, and joint use. It started with 56 member institutions and now this number has doubled, reaching 125 with a student population of three million. About half of the member institutions have provided 309 MOOCs to the platform with an enrollment of half a million students. UOOC has also established relevant rules and regulations to ensure its successful and effective operation, including Charter of UOOC Alliance, Regulations on UOOC Alliance Construction and Operation, and Regulations on Quality Assurance and Mutual Recognition of Credits from UOOC MOOCs.[17] Training sessions both for academics and platform administrators are also held regularly (UOOC, n. d.). But it should be noted that only students from partner universities can register for course study (Wu, 2015). In this sense, it may not be as open as ‘open’ is commonly interpreted.

Course Sharing Alliance of West and East China HEIs (WEMOOC)

WEMOOC was started by Chongqing University in West China in April, 2013 with 28 top Chinese universities as its first members.[18] Later that year, Peking University was elected as the chair of WEMOOC[19]. WEMOOC now has 132 member institutions[20], aiming to cooperate in developing high quality video online courses, constructing a connected platform for these courses, sharing these resources, and recognizing video online course credits (WEMOOC, 2013a). It also has its Regulations on Course Quality Assurance, which covers course development (types of course content, recommendation procedure, and review of technical specifications and instructional design), management of instructional quality, quality evaluation, and relevant research (WEMOOC, 2013).

In addition to CNMOOC, UOOC and WEMOOC, there are several regional/alliance platforms which are hosted by the CNMOOC provider:

- East China Five-University Courses Sharing Consortium (https://edtechbooks.org/-NiGE) – comprised of five top universities in East China, namely Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Fudan University, Zhejiang University, Nanjing University and University of Science and Technology of China.

- Fujian Open Online Courses Education Alliance (http://www.fooc.org.cn/) – with support from the Department of Education (DOE) of Fujian Province, 42 colleges and universities in the province created this alliance in 2016. Currently, there are 69 courses available online. It now also has 20 member institutions from the corporate sector.[21]

- Jiangsu Alliance of CNMOOC – comprised of 11 top universities in Jiangsu Province with only seven courses provided by Nanjing University.[22]

- Open Quality Courses Shared Learning Center of Heilongjiang Colleges & Universities (CNMOOC)– including 39 colleges and universities in Heilongjiang Province and 16 HEIs outside the province. This is a deliverable of a project led by the provincial government to promote joint development and sharing of open online courses.[23]

Some are hosted on the website of MOE’s Higher Education Press:

- Jiangsu HEI Online Course Center – an online instruction platform jointly operated by DOE of Jiangsu Province and iCourse to serve HEIs in the province. Currently, there are 346 undergraduate courses and 133 vocational higher education courses available online. 101 colleges and universities in the province are its members.[24]

- Hebei HEI Courses Online – with 23 member institutions and 112 online courses offered, including MOOCs, open onine courses and SPOCs.[25]

- Shanghai Online Course Center – currently including six top universities located in Shanghai, namely Fudan University, Tongji University, East China Normal University, East China University of Science and Technology, Donghua University, and Shanghai University of Finance & Economics, with 22 MOOCs and six SPOCs available from its member institutions.[26]

- Hubei Online Course Center – offering 156 online courses from 12 HEIs in Hubei Province, including both MOOCs and SPOCs.[27]

- Henan Online Course Center – with 803 online courses, MOOCs, SPOCs, and video open courses available from 26 HEIs in Henan Province.[28]

- Sichuan Online Course Center – having ten HEIs in Sichuan Province as its members, with 189 MOOCs and SPOCs available. [29]

- Guangxi Online Course Center – currently only involving four universities in Guangxi Province which provide nine courses.[30]

- University Open Online Course Alliance of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Bay Area – started by eleven universities from Guangdong Province and established on November 24, 2018. Its members include 52 HEIs, 13 of which are from Hong Kong and Macau. There are now 398 online courses offered. DOE of Guangdong Province promises to provide special funds every year to support the development of online courses (Department of Education of Guangdong Province, 2018). Unfortunately, an Internet search for its website returns zero result.

And some others are hosted by a digital technology company on its course platform – Zhihuishu (Wisdom Tree):

- Open Quality Courses Shared Learning Center of Heilongjiang Colleges & Universities (Zhihuishu – in addition to 93 courses provided by its members - 38 HEIs in Heilongjiang Province, it also introduces 389 courses from HEIs outside the province to the students of its member institutions.[31]

- Shanghai Course Center – started by the Commission of Education of Shanghai, it comprises 30 HEIs from this municipality directly under the Central Government, currently providing 28 courses.[32]

- Open Online Course Alliance of Guangdong Undergraduate Universities – with 66 HEIs from Guangdong Province joining the alliance. 357 courses are available but only 10 are provided by its alliance members.[33]

- The Platform of Higher Learning Online Open Courses in Shandong – led by DOE of Shandong Province, 61 HEIs from Shandong Province form an online course alliance to share high quality educational resources. So far, 39 HEIs have shared 91 open online courses and 379 courses from HEIs outside the alliance are introduced to the platform.[34]

- Hainan HEI Course Sharing Alliance – led by DOE of Hainan Province, 18 colleges and universities in Hainan Province formed this alliance in 2016.[35] Currently, there are 35 online courses shared online.[36]

- Jilin HEI Course Sharing Alliance – comprised of 53 HEIs from Jilin Province, the alliance has 84 courses on offer.[37]

Examples of subject-based partnerships

CNMOOC, iCourse and Zhihuishu (Wisdom Tree) also host some subject-based platforms.

In December, 2014, the Alliance was created with coordination and organization from MOE Instruction Steering Committee of HEI Computer Science Programs, MOE Instruction Steering Committee of HEI Software Engineering Programs, and MOE HEI Computer Curriculum Steering Committee.[38] It is a MOOC-based computer education community with 214 colleges and universities from 31 provincial-level administrative divisions (including three member institutions from the Army).[39] Currently, it offers 37 MOOCs and 23 SPOCs.[40]

The Association was established in November, 2014 with approval from MOE’s Department of Higher Education, joined by software engineering schools from 37 colleges and universities around the country.[41] 38 courses are on offer.[42]

Created by MOE Steering Committee of HEI Library and Information Science, MOE Instruction Steering Committee of HEI Library Science, and iCourse in January, 2017[43], the Alliance has 32 university libraries and 33 schools of management, of information management, and of computer science and IT as well as departments of library information and archive sciences from HEIs around the country.[44]

Jointly constructed by the organizing committee of Contemporary Undergraduate Mathematical Contest in Modeling (CUMCM) and Higher Education Press, the Center provides video open courses, resource sharing courses, MOOCs and SPOCs on mathematical modeling.

Formed by the National Research Center of HEI Instruction, Music Education Society under the Chinese Musicians Association, and iCourse, the Union aims to engage Chinese HEIs and other institutions in developing open online music courses. 10 music courses are available online now.[45]

Established in May, 2016 by a dozen of vocational secondary and higher education institutions in this sector,[46] it now has 15 member institutions but only two courses are available which are developed by its members.[47]

Started by Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine together with 16 other HEIs in the sector in May 2015,[48] it is dedicated to developing and sharing high quality online courses on traditional Chinese medicine. It now has 19 traditional Chinese medicine universities as its members.[49]

This is the platform of Chinese Medical Education MOOC Alliance started by People’s Medical Publishing House together with 53 medical universities as well as Chinese Medical Association and Chinese Medical Doctor Association in 2014. Nearly all medical colleges and universities in China (about 200 HEIs) have now joined the Alliance.[50] Currently, the platform offers 50 MOOCs with another 68 in production and 1866 open courses. It is worth mentioning that some MOOCs and open courses target secondary medical education and medical professional development.[51] 30 universities use their cloud service for SPOC delivery.

China MOOCs for Foreign Studies (CMFS)

As stated on its website,

Initiated by Beijing Foreign Studies University, China MOOCs for Foreign Studies (hereafter referred to as CMFS) was founded on December 23, 2017 in Beijing, China. It is a nationwide nonprofit organization formed by foreign studies universities and colleges endeavoring to promote MOOCs of foreign languages and cultures in China. At present, CMFS has 136 member universities and colleges.

UMOOCs is the official website of the CMFS’ open courses. As an online course platform for universities and colleges, it offers high-quality foreign studies courses online from universities both at home and abroad, and provides course certificates from these universities. The platform enables CMFS members to share their courses and promote the innovative language teaching methodologies and models in China. On UMOOCs, universities can build their own courses, share courses with other universities, and achieve credit recognition.[52]

Quality assurance of regional/alliance and subject-based partnerships

As is obvious from the above examples, whether regional, alliance-affiliated or subject-based, partnerships in constructing and sharing digital educational resources develop at different rates. Some are well developed while others are almost in name only without substantial input and significant engagement from its member institutions.

All alliances/platforms have their quality assurance mechanisms. For example, UOOC members have to follow UOOC Rules for MOOC Production, which covers identification of courses to be developed as MOOCs, course production, course uploading, organization of instruction, and quality assurance mechanism with an attachment detailing technical specifications for creating a video lecture (UOOC Alliance of Local Universities, n. d.). As mentioned earlier, it also puts in place Regulations on UOOC Alliance Construction and Operation, and Regulations on Quality Assurance and Mutual Recognition of Credits from UOOC MOOCs. WEMOOC also puts Regulations on Course Quality Assurance in place to guide course development, management of instructional quality, quality evaluation, and research (WEMOOC, 2013).

The platform of the Shandong alliance - Platform of Higher Learning Online Open Courses in Shandong has to follow rules set down by DOE of Shandong Province (2017) which stipulate in detail measures to ensure the quality of open online course development and sharing. China HEI Computer Education MOOC Alliance (2015) issued its Guidelines on Course Development, including the approval procedure of a course, basic requirements of course production, and support from the alliance. It has three committees in relation to quality assurance, namely Training Committee, Quality Specification Committee and Course Development Committee, each of which has to obey their respective rules and regulations.[53] Shanghai Course Center formulated a series of standards to be followed by its course providers. For example, its Standards for Live-broadcast, Interactive, and Recording Lecture Halls includes very specific processes and technical specifications for the construction of such a lecture hall and its use.[54] It is the same case with its Standards for Sharable Course Video Lecture[55] and How to Watch Live-broadcast Lectures in the Lecture Hall.[56] Moreover, its Instructor Manual provides detailed information about how to prepare instructional materials, how to carry out instructional activities, and how to acquire IT support, among other things.[57] Jilin HEI Course Sharing Alliance has a dedicated section on quality assurance in terms of course development, course delivery and platform operation in its Charter,[58] although relevant rules, regulations, and specifications are not openly available. This is also exactly the case with the Charter of Traditional Chinese Medicine HEI Course Sharing Alliance.[59]

Hainan HEI Course Sharing Alliance (2018) issued its Quality Standards for and Regulations on Sharable Course Development. In addition to requirements for course components, its quality standards section also lays down rules for the design both of online course (instruction) and face-to-face activities (if a course is designed to be delivered in a blended mode) as well as the design for course assessment and course evaluation. Procedures of application for sharable course development and selection of courses to be shared among alliance members are formulated in this document which also specifies types of teacher professional development opportunities to be offered.

5.2 HEI digitalization strategies

As mentioned earlier, there are nearly 3,000 colleges and universities in China where Higher education is a highly centralized sector. Given that educational digitalization is a national strategy, we may as well assume that all HEIs have their own digitalization plans or measures accordingly to be in line with the national digitalization strategy. Nevertheless, it would be impossible to look at the digitalization strategies of all these HEIs. Therefore, we will focus on the 75 universities which are directly under MOE. To be specific, we will examine their 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans, all of which are available on the MOE website (MOE, n. d.), to see what role digitalization is intended to play in the overall development of these universities.

As pointed out earlier, of the 75 universities, 57 mention their achievements in terms of digitalization in the 12th Five-Year period (2011-2015); 48 outline their digitalization strategies for the 13th Five-Year period in an explicit manner, whether in a section or in a subsection, or even in an independent paragraph with a corresponding title; and the remaining 27 HEIs delineate their specific digitalization transformation targets in statements about instruction, learner support, administration and management as well as the university’s for-profit businesses. In this subsection, we will review and discuss the institutional digitalization strategies in more detail.

Institutional digitalization strategies

All the 48 universities whose 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans include institutional digitalization strategies focus on the enhancement of efficiency and effectiveness in administration, management and support as the goal of digitalization transformation. For example, all of them mention strengthening the construction of digital infrastructure, including online platforms, cyber security, resource-sharing environment, data-sharing facilities, mobility, and so on. 35 of them plan to make the most of digital technology to improve decision-making, routine management and student services. 20 of them mention the goal of constructing or upgrading their digital libraries to better support research as well as learning and teaching. Staff capacity building, inter-university collaboration in resource sharing and instruction, as well as credit recognition and transfer are also specifically mentioned in the digitalization strategies of some universities.

In sharp contrast to the overwhelming importance attached to administration, management and support services, innovation in instructional models and in modes of learning are specifically mentioned in the institutional digitalization strategies of 18 universities although as many as 74 universities specify their targets for instructional innovation elsewhere in their development plans.

Specific intended digitalization targets

Take Renmin University of China (RUC) for example. RUC’s digitalization strategy is comprised of three parts (RUC, 2016, pp.70-72). The first aspect is IT-driven transformation of and innovation in instructional and research models. When it comes to instructional models, the targets include: (1) transforming the existing digital environment into a smart one; (2) enriching and improving high quality digital educational resources and software tools; (3) adopting a variety of instructional methods, for example, heuristic, inquiry-based, discussion, and participatory, and encouraging development assessment to establish a new instructional model embodying learner-centeredness; (4) encouraging students to carry out active learning, autonomous learning and cooperative learning using IT such as Cloud Classroom; (5) enabling students to cultivate the habits of taking advantage of IT in their learning so that they can develop personal interests and enhance learning quality; and (6) strengthening student’s abilities to raise, analyze and solve problems in an online environment. As for innovation in the way research is conducted, the targets include: (1) establishing a scholarship resources center; (2) constructing an IT-based platform for research collaboration and communication; and (3) developing a high performance computing platform to support cutting-edge research.

The second aspect is the construction of three integrated platforms for students, faculty and administrators/managers respectively on the foundation of the university’s OA system. The student platform is to support students from enrollment, registration, orientation, course study, graduation, employment guidance to alumni membership. The faculty platform is to have multi-functions, namely, as an online course platform for teachers to prepare their lectures, carry out instructional activities, mark assignments, and organize examinations and enter their scores; as a research platform to provide research resources and support; as a management platform for faculty recruitment, appointment and promotion, remuneration and reimbursement, among other things; and as an administrative platform to improve administrative efficiency by optimizing digitalized management in such areas as finance, university assets and logistics with the aim of shifting from a traditional, hierarchical approach to a flatter management structure.

The third aspect is the establishment of an agile, smart, open, and sharable digital environment, including user center, data center, application center, developer center, high-speed campus network and multi-media facilities. It is of significant relevance to this chapter that this environment is also intended to (1) explore IT-based approaches to inter-university cooperation; (2) develop an inter-university, joint accreditation system with the aim of integrated management of inter-university users; and (3) increasingly share library resources, courseware, and online courses among universities, innovate inter-university online instruction models, and explore mechanisms for credit accreditation, recognition and transfer among universities.

Elsewhere in RUC’s 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plan, in its Goals and Actions section, RUC commits to significantly speeding up the development of digital courses by allocating more money for the purpose and innovating their development and business mechanisms, which is considered as one of the actions to achieve the goal of optimizing undergraduate curriculums (RUC, 2016, p. 23).

In reporting their achievements during the 12th Five-Year period (2011-2015), 33 of the 75 MOE-affiliated universities mention the development of digital educational resources, including MOOCs, SPOCs, video open lectures, state-benchmarking online courses and so on. The number has increased to 55 when it comes to digital educational resource development as intended digitalization targets during the 13th Five-Year period. Many universities even specify the number of digital educational resources to be developed over this period. For example, Table 1 is the development targets of Beijing Normal University (BNU) for digitalization set in its 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plan (BNU, 2016a, p.13).

Table 1

BNU’s intended targets for digitalization over the 13th Five-Year period

| Item |

Intended number/percentage |

| Smart classroom (%) |

15 |

| Undergraduate MOOCs |

75 |

| Postgraduate MOOCs |

25 |

| High quality online undergraduate course resources (%) |

10 |

| High quality online postgraduate course resources (%) |

10 |

| Undergraduate student studying for-credit MOOCs |

1 MOOC per person |

Both ‘joint development’ and ‘sharing’ are high-frequency words in these 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans, which are set in accordance with a path of innovative, coordinated, green, open and shared development which was proposed at the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee in October, 2015. Therefore, it is nothing unusual that the ideas of joint development and sharing are reflected in the 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans of Chinese public universities. Of the 75 MOE-affiliated universities, 66 describe their ‘joint development’ measures and targets, and 73 set forth their ‘sharing’ measures and targets. Nevertheless, a content analysis show that only seven universities’ joint development efforts are concerning inter-institutional development of digital educational resources and that 26 universities mention inter-institutional sharing of digital educational resources in their 13th Five-Year (2016-2020) Development Plans. The idea of joint development in these documents is more often referred to as cooperation in other aspects such as joint development of Confucius Institutes with universities in other countries, co-construction of laboratories and research centers with foreign or domestic universities or the business sector, joint implementation of practicum and/or internship programs with other social sectors, and so on. As for sharing, as mentioned above, slightly over one-third of the universities have plans to promote inter-institutional sharing of digital educational resources. In the remaining two-thirds of the cases (47 universities) where sharing is not concerning digital educational resources, sharing is more often intra-institutional, rather than inter-institutional.

Institutional governance and support structures