This study contributes to the field with an international comparative approach to further understand the factors behind (O)ER infrastructure at the national level, institutional level and micro level (teaching and learning), some of which started to be covered separately in the Open and Distance Education volumes (Qayyum & Zawacki-Richter, 2018; Zawacki-Richter & Qayyum, 2019). This study´s findings could serve as a wake-up call for national/provincial organisations, to see countries comparatively reviewed and therefore justify their push for the improvement of (O)ER infrastructure in HEIs, as well as for individual HEIs and faculty members.

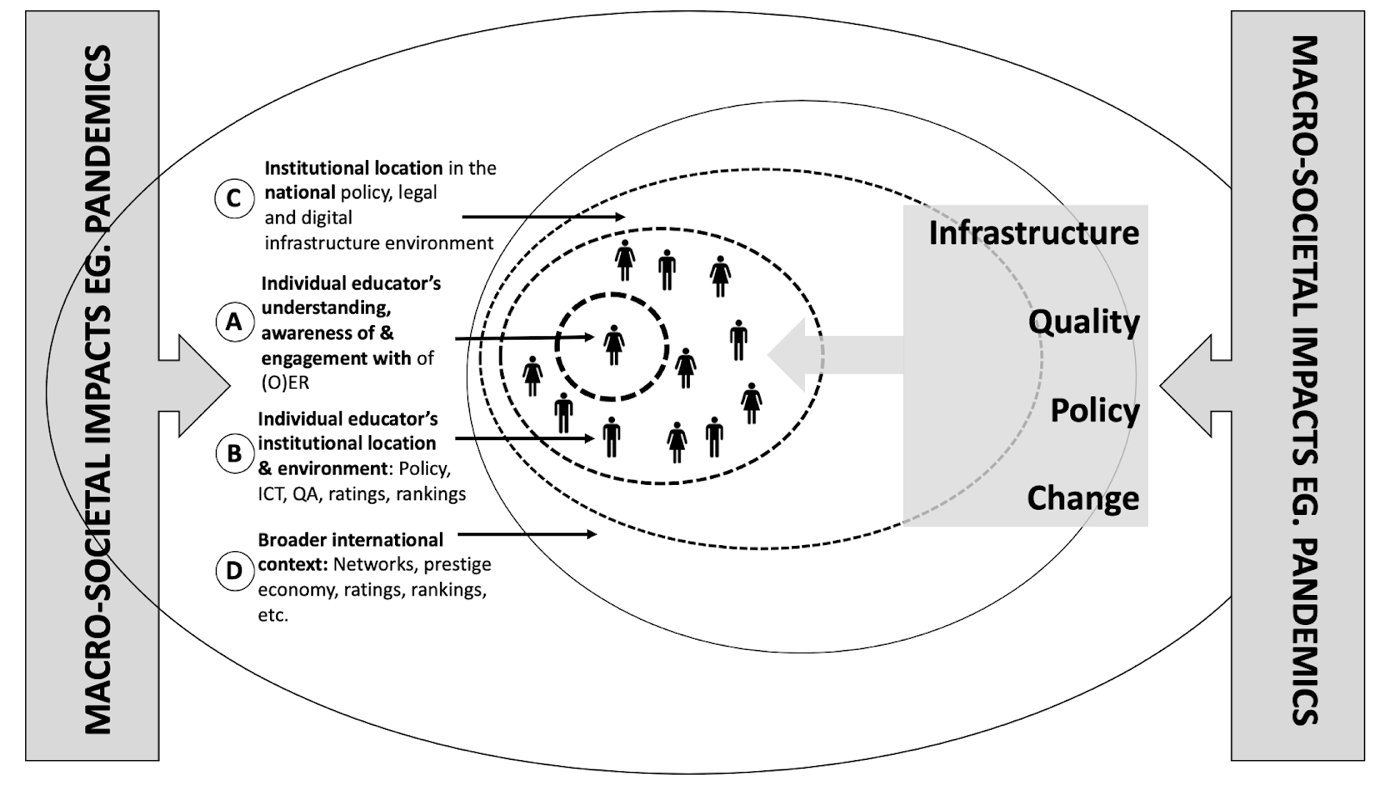

Despite the technological focus of the project EduArc, it is vital to acknowledge that it is not possible to understand national and institutional (O)ER infrastructure, and the associated support elements, without analyzing and understanding the differences of context and culture, as became clear from the analysis above, also in line with recent literature (Jung & Lee, 2020). Aspects such as the political context and the socioeconomic situation have been shown to be a major influence on how HE (O)ER infrastructures are - or are not - developed and change takes place. National and provincial legislation and recommendations, as well as measures for promoting change such as the provision of funding or the acknowledgement of merits, influence the development of (O)ER infrastructure in HE. Quality assurance mechanisms, such as the development of standards and ensuring its compliance, may be in place to ensure not only the interoperability between infrastructure but also the quality of (O)ER contents. A general overview of these elements can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Relations between the elements of the study, the levels and the macro-societal impacts. Source: report of South Africa by P. Prinsloo and J. Roberts.

On the other hand, as previously asserted by Bossu, Brown and Bull (2014), the OER movement has moved more efficiently and effectively in countries where national support was provided, therefore further top-down approaches are needed at both the macro and meso levels. However, this is not enough, and factors related to the institution and the faculty members are also relevant. For example, at the meso level, institutional awareness of the importance of OER and co-participation with the educational community are elements to be considered. At the individual level, the OER adoption pyramid (Cox & Trotter, 2017) has provided a suitable framework to understand academics’ (O)ER related factors and the relevance of professional development and provision of incentives in relation to increase capacity and individual volition, respectively.

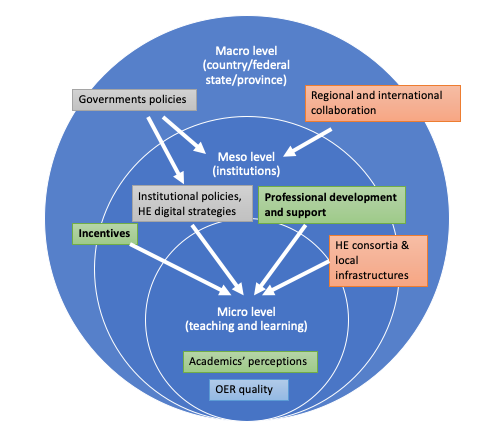

Each country showed different dynamics in relation to the connections between macro, meso and micro levels, but those general aspects seem to be common (see Figure 2). Others were more concrete but could be integrated in broader aspects. For example, in the case of Japan and Korea, peers’ behaviors and beliefs were mentioned as relevant elements at the micro level, unlike other cases. Another example is Canada, where the relevance of OER champions to push the OER movement was determined as cornerstone (micro level), but it was not reported in other cases. The role of libraries in (O)ER (meso and micro level) was recurrent in the cases of Canada, Australia and Spain, but not that prominent in other countries.

For all the cases, national or federal policies and funding at the macro level had a key influence on institutional level (policies, strategies, infrastructures) and these, in turn, on the individual level (especially for individual, social and institutional volition). Even though these dynamics exist, their relevance is also dependent on institutions in the same country, which also promote diverse kinds of professional development and support that go often along with macro and meso level policies and line of incentives. In addition, results at the micro level clearly show that there is still much to do in all the countries for individual (O)ER adoption, due to diverse reasons; e.g. lack or insufficient incentives, lack or insufficient professional development and support, insufficient institutional support or academics’ perceptions and concerns about copyright issues.

Figure 2

Dynamics between macro, meso and micro level. Elements are distinguished by background color (orange for infrastructures, grey for policy, cyan for quality and green for change). Source: Marín, Zawacki-Richter & Bedenlier (2020).

In terms of (O)ER infrastructure, issues of discoverability of (O)ER, interoperability between (O)ER systems and the need for improved repositories and metadata specifications (e.g. related to license, evaluative comments, etc.) were present in many of the countries of the study. The analysis at the macro, meso and micro level shows that a solution of a hub to collect metadata, as well as improved metadata specifications, is still needed, not only for the German context but, we could also venture, for the global and international context too. Faculty members around the world need to be provided with (or co-develop) easy ways for accessing, using and publishing (O)ER, as well, as for remixing, sharing and adapting OER, accordingly to what the author’s licenses allow.

Current studies regarding the use of (O)ER and their repositories during COVID-19 are still scarce but some national, institutional and individual experiences show that an important increase that may have relevant consequences and impact in the different levels, and especially, in academics’ teaching practices, but also in the (O)ER infrastructures. This may be even more true for OER, for the use of which a framework, recommendations and a set of guidelines have been already developed in the context of the pandemic (Huang, Tlili, Chang, Zhang, Nascimbeni, & Burgos, 2020). Therefore, future work could consider more concretely the differences and similitudes between countries regarding these practices and (O)ER infrastructures and encourage ways of promoting them at the three levels.