1. Introduction

1.1 Overview of Higher Education and Digital Transformation

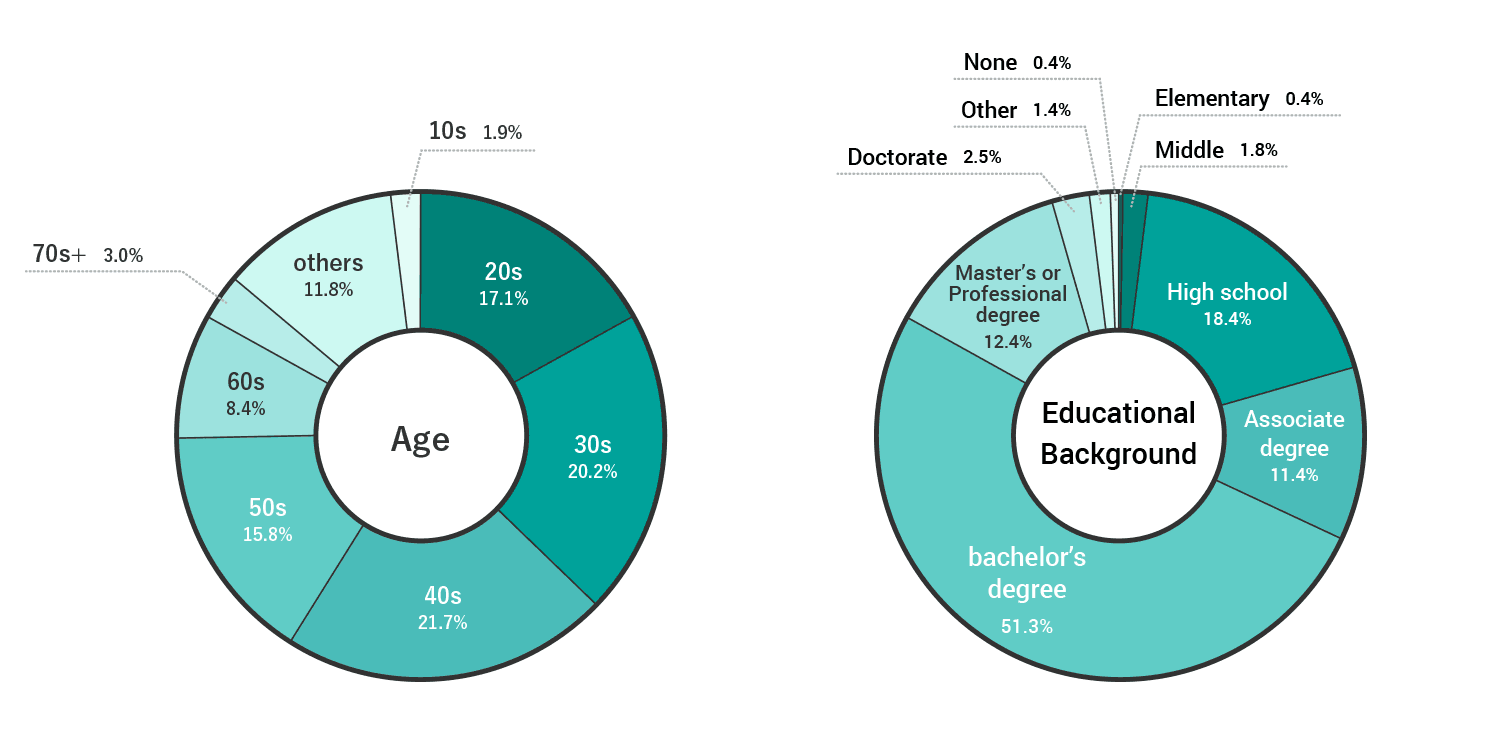

Higher education institutions (HEIs), especially private universities and colleges which comprises around 80% of HEIs, in South Korea (Korea hereafter) and Japan have made significant contributions to the socio-economic development of each country.

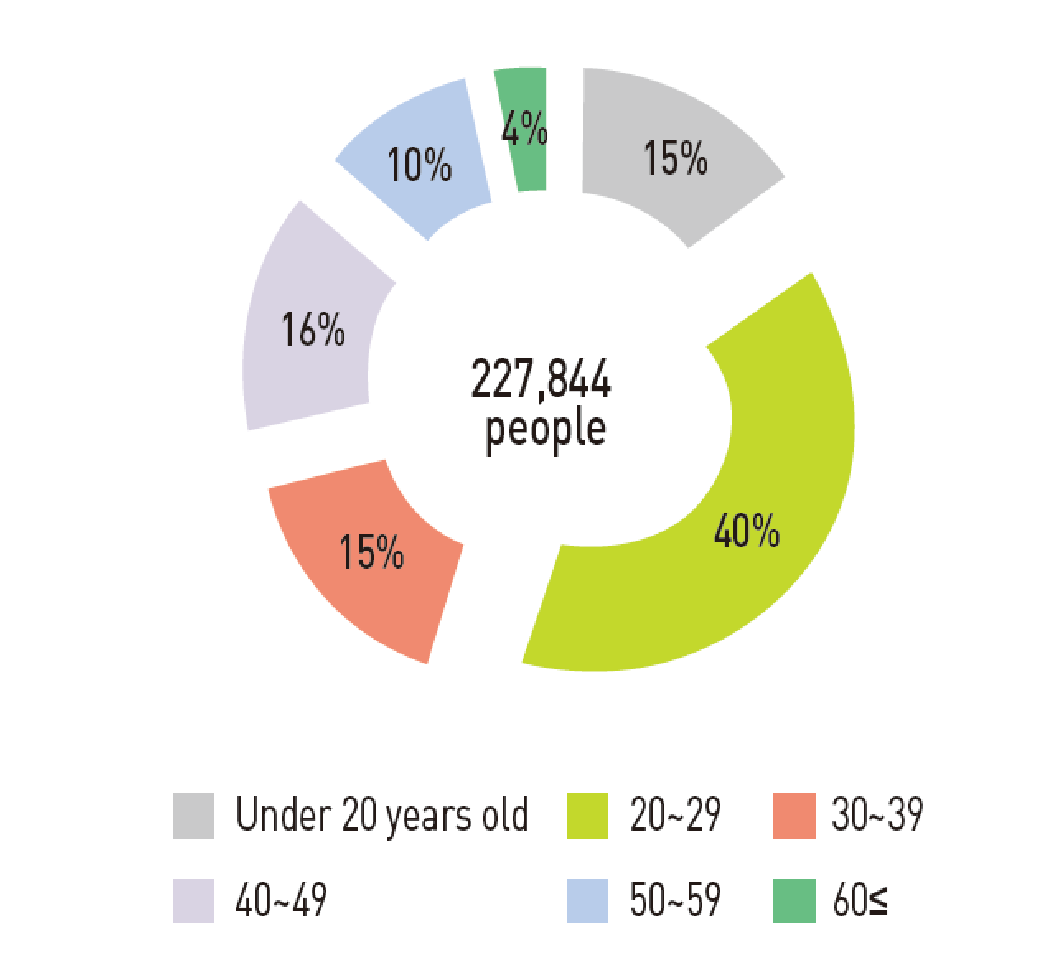

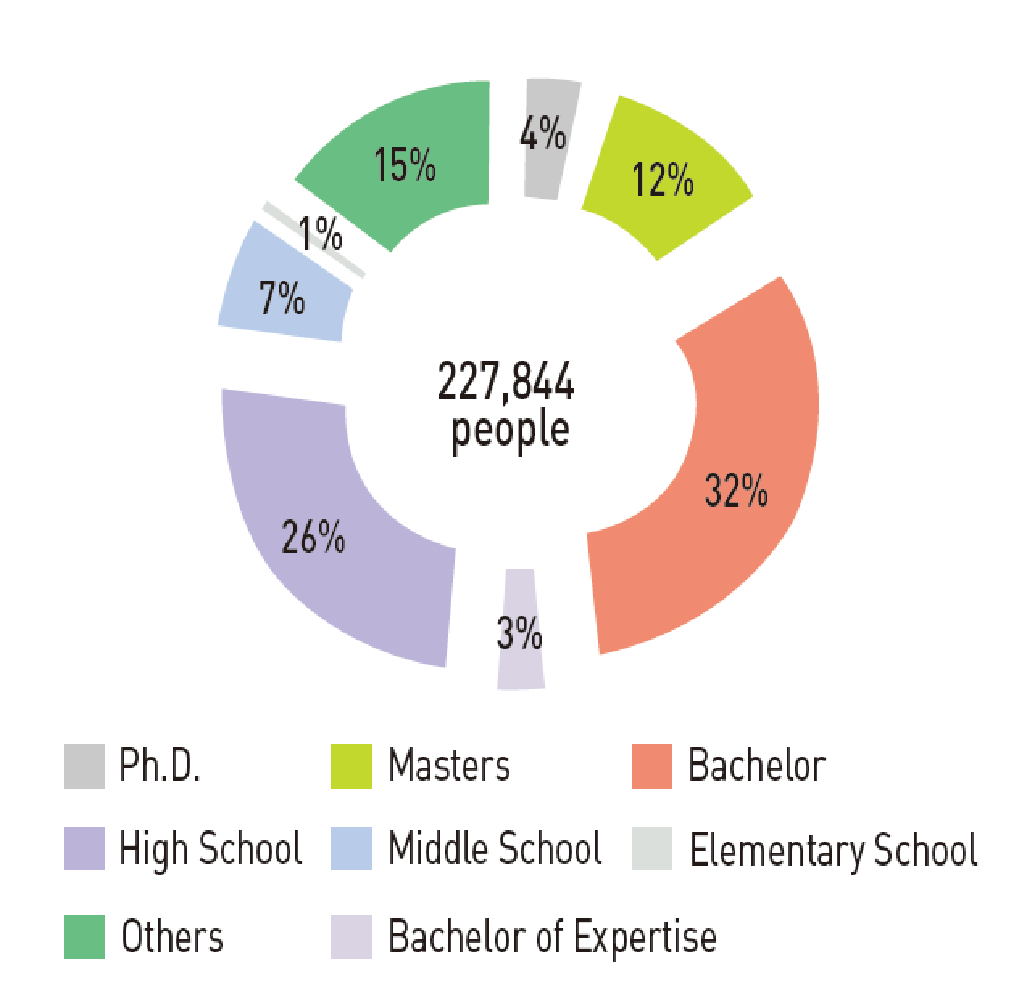

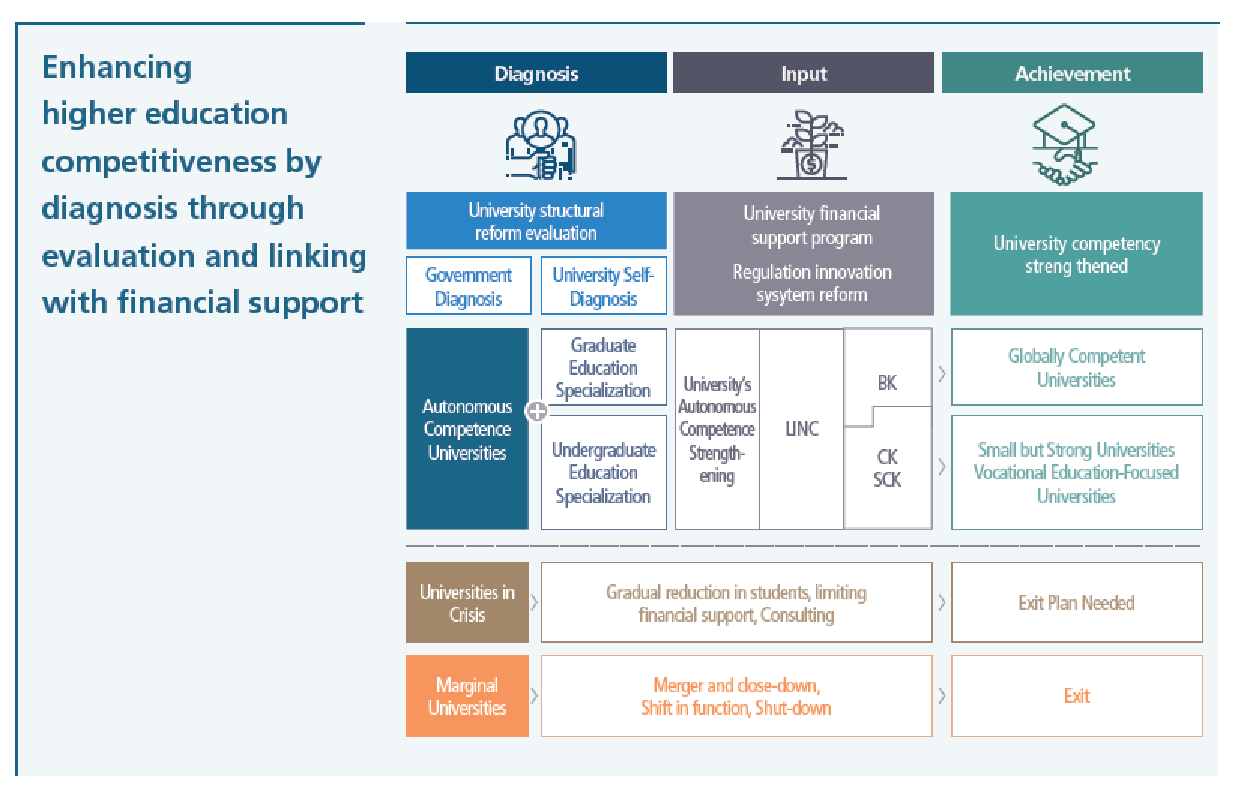

With a population of 51.5 million, Korea has over 3 million university students enrolled in 359 HEIs which include 191 universities awarding bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral and professional degrees, and 137 colleges awarding associate degree (KERIS, 2018). It also has the Korea National Open University, 21 cyber universities offering bachelor’s and master’s degrees and lifelong education programs mostly online, and corporate universities and other types. Recent reforms in higher education in Korea emphasize: 1) diversifying roles and functions of different types of HEIs to meet changing needs of the society, 2) prioritizing knowledge creation rather than knowledge transfer, 3) addressing changing curricular and financial needs by adopting more flexible and efficient models for education, management and governance, and 4) promoting academic-industrial cooperation (MOE Korea, 2016; MOE Korea, 2017a; Leem et al., 2015; Ryu et al., 2011).

With a population of 127 million, Japan has over 2.8 million university students enrolled in 1,200 HEIs which include 778 universities awarding bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral and professional degrees, and 395 junior colleges awarding associate degrees (MEXT Japan 2018). In addition, it has the Open University of Japan, a distance teaching university offering university degree programs and lifelong education, the Cyber University, an online university established by SoftBank awarding bachelor’s degree in IT related areas, and a few other types of institutions. Recent reforms in Japanese higher education focus on: 1) strengthening the functions of different types of HEIs by empowering individual universities (MEXT Central Education Council, 2018), 2) improving the quality of learning to respond to future changes and create new values, 3) proving quality higher education in each region/province considering demographic changes in the whole higher education system, and 4) addressing issues related to diversity, flexibility, and quality assurance.

When it comes to digital transformation, Korean universities have achieved a higher level of ICT access, utilization and skills compared with their counterparts in Japan. This could be accounted for by differences in the two governments’ policies and specific action plans, funding schemes, and universities’ enthusiasm, planning and operational management. This could also be due to the fact that Korea has a centrally supporting agency (the Korea Education and Research Information Service or KERIS) that promotes innovative initiatives, development projects and academic research related to ICT use in education ranging from primary to higher education, while Japan does not. In developing and sharing of (open) educational resources or (O)ER and MOOCs for higher education, the two government agencies, KERIS and the National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE), play a key supporting and coordinating role in Korea whereas no nation-wide system and government supports exist in Japan.

1.2 Purpose and method of macro-, meso- and micro-level studies

The main purpose of this report on the macro-, meso- and micro-level studies was to investigate four aspects (infrastructure, quality, policy, and change) in the development, utilization, and dissemination of (O)ER in HEIs in Korea and Japan at macro (national), meso (institutional) and micro (individual and course) levels.

The macro-level study aimed to examine national-level infrastructure, quality assurance system, policies and changes made with regard to (O)ER and their creation, utilization, dissemination and evaluation. To achieve this aim, the study employed a comprehensive document analysis as an appropriate method. Documents included recently published academic articles, government and other public documents, media news, and other sources from Korea and Japan.

The meso-level study aimed to explore institutional-level infrastructure, quality assurance system, policy and change aspects in the development, utilization, dissemination, and evaluation of (O)ER. For this purpose, in-depth analyses of relevant documents were conducted and interviews with key personnel who had been engaged in OCW or MOOC initiatives in five cases (two universities in Korea and three universities in Japan) were conducted. Across the cases, questions were asked regarding: regulatory frameworks existing within HEIs, actors involved in building and implementing such frameworks, joint efforts in creating infrastructure for the dissemination of (O)ER, existence of subject-based platforms, communication and exchange between repositories and servers, and partnership between public and commercial entities.

The micro-level study aimed to examine course- or individual instructor-level infrastructure, quality, policy, and change in the development, utilization, dissemination, and evaluation of (O)ER. To achieve this purpose, analyses of relevant documents, websites and previous research were conducted and interviews with two local experts who had been engaged in OER initiatives in both countries were conducted to validate the data collected from three case studies (two from Korea and one from Japan). Across the three cases, questions were asked regarding: faculty members’ knowledge on the existing infrastructure, their preference for certain technologies and working conditions in creating and utilizing (O)ER, types of (O)ER frequently adopted in teaching and functionalities helpful for faculty members to edit (O)ER and collaborate with others.

2. Macro-Level Analysis

2.1 OER Infrastructure

Japan

The National Institute of Informatics (NII) provides information networks and services exclusively for academic institutions (NII Japan, n.d.). NII manages the Science Information NETwork (SINET) which was established in 1987 as a high-speed, nation-wide campus backbone network for Japanese universities. While SINET provides the universities with an Internet connection, each university needs to physically connect to the node national universities using a commercial network. NII also promotes the use of Eduroam JP, which allows the enrolled faculty members or students at Japanese universities to use the Wi-Fi network of visiting universities with their own username and password.

Furthermore, NII has developed and managed the Academic Information Circulation system (CiNii), which offers an open access database service for articles, books, dissertations, reports and other types of academic resources created and accumulated mainly by Japanese universities, research institutes, journals, books and other publicly funded projects. CiNii provides Web API (Application Program Interface) for system linkages, and it offers the OpenURL receiving and sending functions. NII has also operated the Academic Access Management Federation called GakuNin since 2009. GakuNin is a federation consisting of universities (main users of online academic resources) and publishers (main providers of such resources). Once the federated authentication is established, the users of a university can access online resources (i.e., e-journals and reports) of other universities and commercial publishers in Japan with a single log-in on and off campus. NII also funds the creation and sharing of institutional repositories of university in-house journal articles, bulletins and dissertations. Institutional Repositories Database (IRDB) collects and disseminates metadata of the contents registered in those institutional repositories. JPCOAR schema is a new metadata standard developed by the Japan Consortium for Open Access Repository (JPCOAR) and has been applied to the content creation of the institutional repositories.

To promote resource sharing and collaborative research among universities, the Research Organization of Information and Systems (ROIS) has created the Inter-University Research Institute Corporation to promote sharing of research facilities, graduate courses, academic data and research materials produced by research institutes and departments of the Japanese universities and support collaborative research with other universities, research institutions and private sectors in Japan and other countries.

The purpose of the aforementioned nation-wide systems such as CiNii, GakuNin, IRDB, and ROIS is to develop, link and share the research products of Japanese universities and of other organizations. No nation-wide system exists for the development and sharing of (open) educational (teaching and learning) resources. It may be possible in the future that OER and other educational materials created by individual universities could be shared via ROIS or another existing system.

Japan OCW, which was established in 2005, promotes the open sharing of courses provided by its member universities and operates mostly based on membership fees (Total 19 universities, NGOs and companies as its members in 2019). Each member university offers their OCW on their website and thus no host server exists.

JMOOC, established in 2013, is also a membership-based organization with no government support. Members include both private companies and universities (Total 79 members and 140 courses in 2019). Courses are offered in four different providers: Fisdom, gacco, and OpenLearning Japan, each managed by a different company, and OUJ MOOC managed by the Open University Japan. Its steady growth has been reported in the website.

Korea

The Korea Education Network or KREN, a non-for-profit organization, has created and managed the Education Network since its creation in 1991. Until 2001, the Seoul National University and other national universities in eight different regions oversaw the Network. Since 2001, the Education Network has been using a commercial network service to accommodate the rapidly increasing communication needs of the universities and to stabilize the service for 24 hours/365 days, with the matching funds from the government and the university. So far 356 (out of 359) higher education institutions are using this network. The network fee is paid jointly by the individual universities and the government.

Eduroam or Educational Roaming is another type of infrastructure that offers a global wifi roaming service. With over 50 member universities and research institutions, it shares their wifi network service and their academic information services.

Since the development of the e-Campus Vision for Higher Education in 2002, the Korean government has supported the establishment and implementation of 1) e-Learning support centers in the universities across ten different regions of the country and funded collaborative content development among the universities located within the same region, 2) the Integrated Administration and Finance System for Universities, and 3) the Crowd-based Integrated Academic Affairs’ System, which will be linked to the Universities’ Resources Management System in 2020.

KERIS is at the center of developing, managing and evaluating various types of academic resources (both research products and open educational resources) for higher education with funds from MOE and member institutions.

- First, for academic research, KERIS obtained university licenses to access several overseas academic databases so that researchers of all universities in Korea can access them without individually subscribing to those databases. This overseas database service aims to bridge the information gap among the universities and promote competitiveness of Korean researchers.

- Second, RISS, founded in 1998 by KERIS, is a service to all university students and faculty members in Korea. As explained above, it aims to enhance Korea’s research competitiveness by providing all academic research resources including national and foreign journals, e-learning courses, publicly funded project reports and other open resources. It has become the main source for academic research with over 4.5 million accumulated members and around 10 million monthly search clicks. It is now offering other public resources owned by private and other types of organizations and external portal services following the government 3.0 policies for disclosure and joint use of public data.

- Connected to RISS, the digital distribution system (dCollection), which was established in 2006, has been offering the latest version of full texts and other research outcomes created by individual universities and organizations along with all other academic resources served in RISS. This system allows all university libraries to access and manage academic research materials created by other universities through KERIS’s RISS. As of 2017, over 240 universities (this number includes almost all universities in Korea which offer a graduate program) were using the dCollection service, and around 40 universities installed the system in their own server.

Unlike Japan where OCW and MOOCs are not supported by the government or public agency, KOCW and K-MOOC are supported by two Korean government agencies, KERIS and the National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE), respectively.

For the dissemination of OCW and other open materials created by Korean universities, KERIS has developed and managed the KOCW (Korea Open CourseWare) system since 2007 (Leem et al., 2017). KOCW supports the dissemination and sharing of university course lectures and supporting materials, and other theme-based lecture videos (e.g., English conversation, preparation classes for vocational certifications, etc.) to meet various learning demands of the adult learners and students. KOCW provides around 13,000 courses created by the universities, and around 2,300 videos created by the Educational Broadcasting Service, the Vocational Broadcasting Service and other educational institutes. It also provides a global MOOC provider Coursera’s meta data service for about 200 courses.

In the case of K-MOOC, NILE, an MOE-funded national institute for lifelong education, has managed the K-MOOC server centrally since 2015. As MOOCs are considered to be resources for lifelong education rather than materials for formal higher education, NILE, not KERIS, was chosen as the hub institute for K-MOOC. Course developers are the member universities (over 80 universities and 500 courses in 2018) and course users are the general public as well as university students. Currently K-MOOC is searching for a sustainable business model including introducing paid courses and collaborating with private sectors with an expected budget cut from the government in the near future.

Considering educational metadata schemes and components such as Dublin Core or DC Education and IEEE LTSC LOM, KERIS has introduced the Korea Education Metadata (KEM) standards with nine categories (general, life cycle, metadata, technical, educational, rights, relations, annotation, classification) since 2005 and applied them to the development of educational resources. KOCW applies all categories of KEM3.0 but one (annotation). The E-Learning Support Centers established throughout ten regions of the nation collect and manage e-learning courses and other digital materials following KEM3.0 (Ahn & Park, 2009).

A Shared University is a recent initiative funded by the MOE. One such example is developed by 24 universities out of 57 that are located in Seoul, aiming to share courses for credit transfer and joint degree, educational resources, research and educational facilities, job-related data and more, and co-develop and provide MOOCs for citizens in Seoul and beyond. Each member university operates a credit transfer system and MOOCs linked to other member universities.

2.2 Quality of OER

Japan

No standards, guidelines or checklists exist for the quality management of educational resources including OER and MOOCs in Japan at the national level. The JOCW consortium and JMOOC consortium do not offer any consortium-level guidelines to their members. Interviews with a few member universities reveal that the quality guidelines for the creation of materials are left to the hands of the individual universities. Often times, the guidelines prepared by the individual universities are step-by-step procedures to follow but are not necessarily for the purpose of quality assurance of the materials. Some researchers such as Katoet al. (2018) have developed a quality checklist for the development and management of OER at the personal level.

Korea

KERIS provides A Guidebook for Digital Content Development and Management (in Korean) to ensure the acceptable quality of online resources and OCW that are shared among the universities or open to the public (KERIS, 2017). The Guide specifies both minimum required criteria and optional suggestions. Required checklists include:

- Check types of educational materials (e.g., ppt, handouts, links etc.)

- Check if copyright issues of all the materials are cleared (e.g, open licensed? need permission? properly cited? etc.)

- Specify lecture style (e.g., using whiteboard and/or ppt? offering demonstration? etc.)

- Check if any supporting tools are needed (e.g., projector? LCD? other supporting tools?)

- Check lecture time

In addition to the use of this guidebook, KERIS continuously evaluates open digital content and online courses developed under the MOE-funded projects such as ACE (Advancement of College Education), CK (Creative Korea), and CORE (COllege of humanities' Research and Education) projects. In addition, it provides best practices in the use of KOCW and other open materials to the universities.

NILE provides Guidelines for K-MOOC Development and Management to K-MOOC providers. As K-MOOC uses edX platform, the guidelines offered in this booklet consider those of edX. K-MOOC Guidelines include a set of quality criteria (both required and optional quality criteria) and detailed suggestions across the design, development, testing and implementation stages. For example, two required quality criteria related to the learning content at the design stage include: accuracy of content (e.g., no grammatical and logical errors, no missing words, etc.) and sound ethical content (e.g., considering diversity and inclusivity, non-violent, respecting privacy, etc). The booklet is used by the MOOC developers as a tool to assure the development of quality online courses and was also adopted by NILE to assess if the submitted MOOCs follow the required quality criteria in the Checklist.

Moreover, NILE applies the following measures to assure the quality of MOOCs:

- NILE encourages each university to utilize the Guidelines and assign a MOOC project director who manages the whole MOOC development project and works closely with the faculty members/content experts and instructional designers.

- Those MOOCs that are not meeting the quality criteria are returned to the developers for revisions and improvements before resubmission.

- Once submitted, experts in MOOC quality management at NILE review the quality of the course and offer feedback and recommendations for further improvement.

- Finally, the best MOOCs and research and evaluation results are distributed to the K-MOOC members to share knowledge and experience.

2.3 OER Policy

Japan

The necessity to increase government funding for higher education and policy support for promoting donations and investment from the private sector has been emphasized in MEXT’s most recent report in Japan (MEXT Central Education Council, 2018) although the specific plans have not been released. A policy change is expected in the area of information disclose. With the use of public assistance, the universities will be asked to disclose the quality of their education and students’ performance information, as well as the costs of education and research to the public in more detail.

Korea

MOE Korea (2017b) identified several policy areas to be discussed and prepared for digital transformation and resource sharing in the future. Those include:

- Policies to maintain and manage copyrights of KOCW and other open content

- Policies related to personal information and privacy protection with the advancement of digital infrastructure and services

- Management and technical measures to protect online services from hacking attempts

- Measures to specify procedures to collect and manage minimum personal information

- Measures to minimize overlapping parts between KOCW and KMOOC operations by two different government agencies

- Measures to simplify application technologies and apply AI technologies

- Measures to promote active sharing and utilization of KOCW, KMOOC and other digital content

- Measures to share digital contents with developing countries and countries in conflict zones

MOE and other related ministries such as the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, KERIS and NILE are working together to discuss and solve copyright, privacy and safety issues involved in overall digital transformation and resource-sharing in the education sector. KERIS and NILE are clarifying their roles and collaborating in offering and promoting KOCW and KMOOC in a more cost-effective manner. MOE has begun to support and promote the universities to apply AI technologies through various initiatives.

2.4 OER Change

Japan

The e-Japan Strategy released in 2001 is still considered the foremost official policy concerning the national-level ICT strategies in various sectors including higher education. In the acceleration plan for the e-Japan Strategy (IT Strategic Headquarters, 2004, 2017), changes in the following areas have been promoted at the national level:

- Enhancement of ICT security measures in various sectors. In the education sector, cybersecurity human resource development, provision of professional training programs and publicity are emphasized.

- Promotion of digital content creation and distribution. Unfortunately, educational resources from higher education institutions are not included in the category of digital content in this plan.

- Deregulation of laws that have prevented the use ICT in public document storage, meetings and interviews, issuing certifications and other public activities. Changes have been made to save various information (e.g., medical information, tax information and more) in digital format, and conduct meetings and interviews via video/audio-conferencing in ministries and university exams, etc.

- Policy and financial support for the creation of faculties and graduation schools for training of high-level data scientists in pursuit of advancements in IoT, big data, AI and other intelligent technologies.

- Continuous financial support for university reform via University Reform Good Practice initiatives.

Korea

The 2019 MOE budget (MOE Korea, 2018a) includes special funds for:

- Globalization of higher education via increased global experiential learning opportunities for students to promote global leadership and the development of pre-service teachers' global and multicultural competency.

- Increase of graduate students' research capabilities and global competency through BK21Plus initiative.

- Venture entrepreneurship efforts by universities.

- Young researchers in medical and life science fields.

- Establishment of both face-to-face and ICT-based life-long education system of universities.

MOE are working on the following changes that are closely related to digital transformation and resource-sharing in higher education (MOE Korea, 2018b).

- Introduction of online nanodegrees in the areas with high social demand.

- Development and dissemination of vocational MOOCs in collaboration with community colleges.

- Development of AI and 4th industrial revolution related K-MOOC.

- Development of an integrated MOOC platform to distribute MOOCs from both public and commercial providers.

3. Meso Level

3.1 Cases of OER

Seoul National University (SNU)

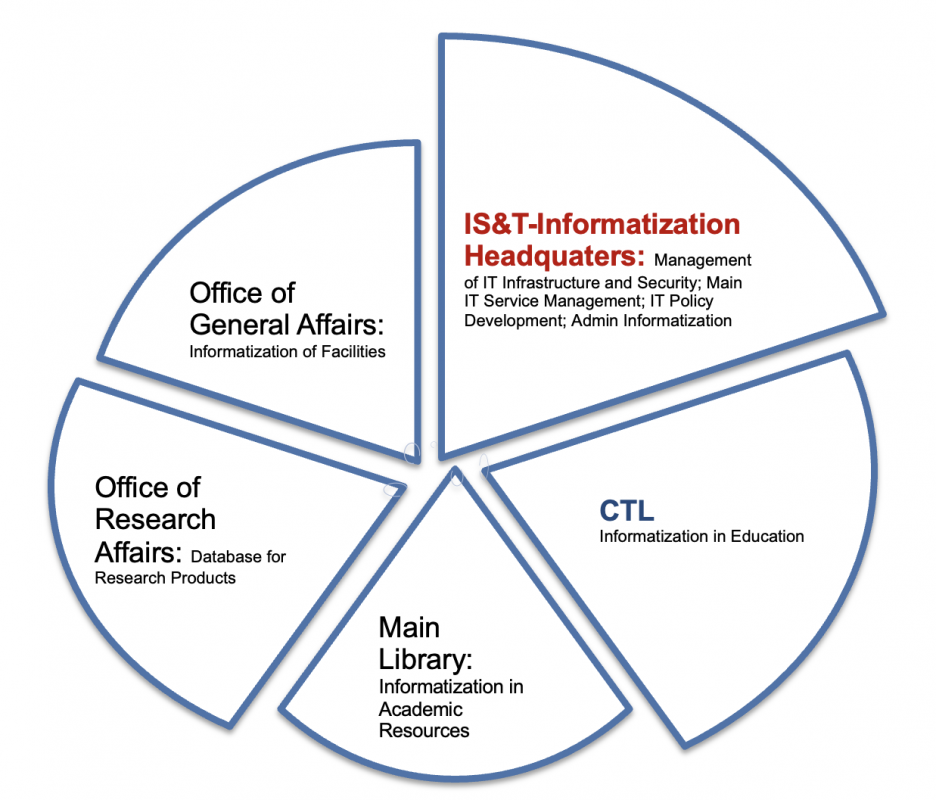

SNU is a top national university located in Seoul, South Korea (Korea hereafter). It offers 13 MOOCs in English on edX including courses in international policies in the Korean peninsula, economics, and robot mechanics. In addition, as of September 2019, it is offering 20 courses in Korean language on K-MOOC and has uploaded 172 OCW on the KOCW server since 2011. SNU’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), established in 1975 as the Instructional Media Center and renamed as CTL in 2001, is responsible for the development, delivery and quality assurance (QA) of OER and other multimedia and online educational resources for SNU classes. CTL has 43 staff members working in six teams: Teaching and Learning Support, Writing Support, E-learning Content Development, Multimedia Production, PR, and Administration Teams.

C University (CU)

CU, a large private university in the southern part of Korea, is a member of both KOCW (offering two KOCW courses in the engineering field and K-MOOC (offering one MOOC in the field of history of literature). CU’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL), founded in 2000, is responsible for the development, delivery and evaluation of CU’s online courses, OCW, MOOCs and other educational resources, and teaching and learning support. It has eight staff members who work closely with CU faculty members. Like several other universities in Korea, CU collaborates with other campus-based and cyber universities and consortia such as Seoul Digital University, KCU Consortium, Yongnam University and more, and shares their online courses for credit transfer. It also shares MOOCs created by other universities for credit transfer.

University H (UH)

UH, a large-scale national university in Japan, is the member of both JOCW and JMOOC. At UH, the Center for Open Education (OEC) is responsible for UH’s OCW, MOOC and other OER development and delivery, and training and support for UH’s faculty and staff members regarding ICT use and OER development. OEC is responsible for 1) UH OCW (creating and sharing OCW with other Japanese HEIs), 2) OEC MOODLE (supporting MOODLE-based e-learning creation), 3) Academic Commons for Education or ACE (creating and managing open courses with seven universities located in Hokkaido prefecture), and 4) MOOCs on JMOOC and edX.

International Christian University (ICU)

ICU a small private liberal arts college, is a member of JOCW. The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is responsible for the development and dissemination of ICU OCW and other educational resources (e.g., ICU-TV). Since 2009, it has developed over 50 OCW course, mostly in English, in various fields including English for Liberal Arts, general education, Japanese language program, and other academic major fields. Some OCW courses are prepared for high school students.

University of Tokyo (UTokyo)

Utokyo is a top national university in Japan with 2,484 professors, 3,937 other types of teaching staff members, 1,524 administrative staff members, 14,071 undergraduate and 14,239 graduate students. The Center for Research and Development of Higher Education (CRDHE) manages UTokyo’s OCW and MOOCs. UTokyo was the first university in Japan which offered MOOCs with global MOOC providers. Since 2013 when it offered two courses on the Coursera platform, it has added five more to Coursera and eight to edX as of December 2010. At the beginning stage, UTokyo designed MOOCs as information for international students who wished to come to Japan (Fujimoto et al., 2017), but now it focuses more on reaching out to the world with their courses and fostering online learning communities.

3.2 OER Infrastructure

Korea

As noted in Keskin et al. (2018, pp. 198-199), Korea has assertively and publicly supported the partnerships with international organizations to promote OER and open education. Korea partners with the World Bank’s Open Learning Campus where several Korean institutions including SNU, Seoul Metropolitan Government, and Korea Development Institute offer their online courses and video lectures. Korea’s National Digital Library of Congress also works with Creative Commons Korea and provides open licensing to their content. All these national and institutional level efforts and partnerships discussed above and below evidence that Korea positions OER and open education as a key strategy for national competitiveness in both formal and lifelong education sectors.

KOCW and K-MOOC as OER are created, managed and disseminated mainly by two government-funded organizations: The Korea Education and Research Information Service (KERIS) overseeing KOCW and the National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE) that is responsible for K-MOOC. Both organizations are under the auspices of Korea’s Ministry of Education (MOE).

KERIS and KOCW: Development and Infrastructure

Since 2007, KERIS has operated centralized infrastructure – server, platform, network etc. – for KOCW with the MOE funding. As of September 2019, the KOCW server manages 15,777 courses created by 187 universities and 2,373 courses created by 25 other types of organizations including foundations, educational institutions and commercial broadcasting systems. When universities and other organizations develop courses for KOCW, they need to follow the Korea Educational Metadata standard, Korea’s national standard for the development of sharable educational resources. Once the courses are developed, they can be uploaded on the KOCW platform by the course developers and disseminated via each university (or organization)’s course information sharing system or KOCW content server. Upon the request from a university or any organization involved in OCW development, KERIS installs a data provider so that the university or organization can collect real-time course usage data from the KOCW server (Chang, 2015).

There are no subject-based platforms for KOCW. However, the KOCW platform integrates a strong search engine which makes it possible for searching both by academic field and by theme. KOCW has a mobile app on Apple Store and Google Play Store (Figure 1).

Figure 1

KOCW mobile app

KOCW developers are mostly universities and public organizations such as the Korean National Commission for UNESCO, Korea Education Frontier Association, and Korea Copyright Commission. These public organizations tend to use KOCW to educate the public related to their mission. For example, the Korean National Commission for UNESCO offers courses on Education for Sustainable Development and World Heritage, and the Korea Copyright Commission provides courses such as “Introduction to Copyrights for University Students”, and “Contract with Publisher”.

KOCW developers also include several commercial companies. For example, a speech communication company offers KOCW on voice training and lecture skills. Three broadcasting companies provide their broadcasted documentaries and news programs on various social issues on the KOCW server. A dental clinic has two courses on implant technology on the KOCW server as well. KOCW has developed a few special programs which would promote the use of its OER for certain target groups. For example, it provides a list of OCW for 2-yr community college students. This service is titled KOCW College (or KOCWC). In close collaboration and consultation with Korea’s community colleges, KOCWC was created in 2014 with the purposes to support students in 2-yr colleges to improve their learning performance in a systematic manner and offer job-related courses for those 2-yr college students. For these purposes, the KOCWC site lists 1,725 courses in 84 majors and job training courses in ten fields following the National Competency Standards which include the individual’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to perform the duty in a certain industry sector at a certain level, and course metadata. It has a plan to offer more job training OCW which would help community college students and other OCW users prepare for various national-level examinations.

KOCW has a link to ACU-OCW, a collection of OER created entirely in English under the Korean government-funded ASEAN Cyber University Project. ACU-OCW offers 685 OER in various formats (e.g., video, audio, web sites, text, and weblinks) targeting the ASEAN member countries. Its server is now managed by KERIS.

NILE and K-MOOC: Development and Infrastructure

Since 2015, NILE has operated infrastructure – server, platform, network, etc. – solely for K-MOOC with the support from MOE. NILE has also managed K-MOOC’s LMS (Learning Management System), Studio (Course development tool), and K-MOOC Insights (Data management tool). The K-MOOC platform is developed based on the edX platform and its LMS, Studio and Insights are also from edX tools. Table 1 outlines key functions of the K-MOOC platform.

Table 1

Key Functions of the K-MOOC Platform

| Area | Key functions |

|---|

| Course and Content Design | Production and Utilization |

| Course Design |

| Assessment | Quiz |

| Assignment |

| Test |

| Interaction | Discussion |

| Wiki |

| Learning Management | Progress and Attendance Management |

| Learning Support |

| Learning Path Management |

| Certification |

| Data Management | Big data Management |

As of September 2019, the K-MOOC server manages 1,165 courses created by 96 universities. Among K-MOOC courses, eleven 15-week courses are counted as university credit for Korea’s Academic Credit Banking System that was established in 1997 as an open higher education system which recognizes credits gained both in- and out- of universities such as K-MOOC (Usher, 2014).

No subject-based platform is used in K-MOOC. The K-MOOC server is linked to the national Online Lifelong Learner Portal server and the Academic Credit Banking System server, both of which are managed by NILE. But there is no communication between the NILE-managed K-MOOC server and the member organizations’ servers. The K-MOOC app can be found on both Apple Store and Google Play Store (Figure 2).

Figure 2

K-MOOC mobile app

University eLearning Support Centers

Several e-Learning Support Centers have been established within HEIs across Korea’s 10 regions with matching funds from MOE and the universities. Universities in the same region have collaboratively developed and shared online materials and courses for credits and non- credits, linking their network systems. For example, in the Southeast region, 50 HEIs, e-learning companies and research institutes formed an “E-Learning Cluster” and developed online content related to various Korean cultural studies for university credit and shorter vocational training content for lifelong education. But with the end of MOE funding, activities of the Centers have been gradually decreasing.

Other Consortia

Several consortia of HEIs have been formed over the past two decades. For example, KCU Consortium, founded in 1997, has over 80 member HEIs. Its infrastructure is managed by a commercial company commissioned by the Consortium and can serve 100,000 users simultaneously. Other smaller consortia operate their infrastructure in a similar way, or the representative university manages a server for its consortium members.

Japan

OER is officially defined as various types of lecture materials that a learner can use for free. These materials include lecture videos, e-textbooks, learning content objects, educational software and so on (Keskin et al., 2018, p.195). Two main organizations are engaged in the development and sharing of open educational resources in Japan: JOCW and JMOOC. These organizations are operated based on membership fees and receive no direct funding from the Japanese government. The infrastructure of both organizations is decentralized. Details of these two organizations and their infrastructure are discussed below.

JOCW: Development and Infrastructure

Inspired by MIT’s OCW activities, the top six universities including the University of Tokyo, Osaka University, Kyoto University, Keio University, Tokyo Institute of Technology, and Waseda University launched a closed Alliance to develop and share their courses online. This Alliance was reestablished as an open consortium called JOCW or Japan OpenCourseWare (JOCW) in collaboration with MIT in 2006 (Keskin et al., 2018). JOCW member universities have shared course syllabi, video or audio lectures, and lecture notes via the JOCW website.

As a consortium, JOCW does not have a centralized infrastructure for its services except it provides links to the OCW webpage of its member institutions, and a repository of all members’ OCW is available to the member institutions and the public. In addition, JOCW regularly publishes a newsletter to share the national and global news on open education and announce related events to JOCW member institutions.

Individual member institutions of JOCW have established and maintained their own server and platform and created their own portal which is linked to the website of JOCW. JOCW has a repository managed by the Open University Japan (OUJ)–CODE which is a GLOBE (Global Learning Object Brokered Exchange) member organization in Japan.

Unfortunately, the JOCW consortium has not attracted the attention of Japanese HEIs. As of July 2018, it has only 13 regular member institutions and 7 associate member institutions, and these numbers cannot be updated as the JOCW website has been down since the summer of 2019. Several scholars (e.g., Jung & Lee, 2015; Takeda, 2014) criticize the closed culture of Japanese educational institutions and the lack of support at both governmental and institutional levels and their effects on the development and implementation of OER for teaching and learning.

JMOOC: Development and Infrastructure

JMOOC or Japan Massive Open Online Education Promotion Council, founded in 2013, operates as a corporation with over 80 member institutions including universities, private companies and academic and professional associations as of September 2019. No communication and exchange structure is set up between the servers and repositories of the member institutions in JMOOC.

JMOOC offers over 140 courses (a few courses charge a fee and face-to-face components in free MOOCs are also charged) and attracts more than 500,000 learners, mostly from Japan. Matsunaga (2018) reports that JMOOC is a multiplatform consisting of four platforms:

Most of the JMOOC member universities use Gacco or OpenLearning Platform, whereas Open University Japan uses its own platform, OUJ MOOC. Fisdom offers several MOOCs from commercial sectors. There is no course-sharing mechanism among these platforms except that the JMOOC homepage offers a course search function across the platforms. No mobile app at the JMOOC level can be found but Fisdom offers a mobile app for its courses (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Fisdom mobile app

Commercial entities are active members of JMOOC and participate in the creation and delivery of MOOCs in collaboration with universities and academic associations. Some of them have opened their own MOOC service and delivered small private online courses or SPOCs via their MOOC platform.

3.3 Quality of OER

Korea

KOCW - Diverse QA Measures and Link to Other QA Standards

Until 2019, there has been no centralized QA mechanism as KOCW is often used for voluntary sharing. But it has been a common practice that individual universities set up their own QA mechanism in developing OCW or other types of OER as those OER are open to the public and other universities and an existence of a QA mechanism for OER is one of the MOE’s university evaluation criteria.

In 2019, KERIS introduced a formal QA system for KOCW and began to review existing KOCW courses that were voluntarily uploaded by individual universities in the past 10 years and requested that the universities improve or delete their courses if the quality of such courses did not meet the standards. With the introduction of KERIS’s centralized QA system for KOCW, the universities have begun to refine and elaborate their QA system. For example, SNU’s CTL developed internal evaluation criteria[1] for OCW and other types of OER and formed the Content Quality Management Committee which is responsible for QA of SNU’s OER including OCW.

Beside the introduction of a centralized QA system for KOCW, KERIS provides A Guidebook for Digital Content Development and Management (in Korean) for the development of various types of OER and other educational resources (Lee et al., 2017). The Guidebook specifies both minimum required quality criteria and optional suggestions. Required criteria include:

- Check types of educational materials (e.g., ppt, handouts, links etc.),

- Check if copyright issues of all the materials are cleared (e.g, open licensed? need permission? properly cited? etc.),

- Specify lecture style (e.g., using whiteboard and/or ppt? offering demonstration? etc.),

- Check if any supporting tools are needed (e.g., projector? LCD? other supporting tools?), and

- Check lecture time.

KERIS guidelines for the development of OER do not follow a particular regional or international QA standards. Instead, they integrate key QA criteria for various standards and suggest common QA guidelines as listed above. They also recommend OER developers to follow the Korean Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 that are developed based on international standards.

K-MOOC: Centralized QA Mechanism and Link to International Standards

NILE operates a standardized QA mechanism for all K-MOOC developers. The first step is to evaluate a course plan prior to finalizing its funding to support MOOC development. Key evaluation criteria include:

- MOOC project team (if the project team has vision and strategies, matching fund, staffing, and previous experiences),

- MOOC development (whether there is a need to develop as a MOOC including appropriateness of content, instructional design and interaction strategies, assessment plan, instructor’s expertise and teaching competencies),

- MOOC implementation (if there is a plan for QA, MOOC PR and dissemination), and

- extra points for linking to the Academic Credit Banking System.

It is worth noting that a plan for QA is included as an important criterion for funding K-MOOC during the initial MOOC selection stage.

Once a course plan is selected for funding, a consortium or a university must follow its QA plan for its MOOC development. To support MOOC developers, NILE provides Guidelines for K-MOOC Development and Management. The Guidelines include 32 criteria across 14 areas at 4 development stages as shown in Table 2 and add detailed explanations of each criterion with examples and best practices. K-MOOC developers are strongly encouraged to use these guidelines as a QA checklist during the course development and implementation.

As shown in Table 2, NILE conducts two evaluations during the MOOC development process: one at the Design Stage, and anther at the Testing Stage. This two-stage evaluation is conducted by a team of both internal and external content experts and educational technologists. Those MOOCs that are not meeting the quality criteria are returned to the developers for revisions and improvements before resubmission. In addition, the best MOOCs and research and evaluation results are distributed to the K-MOOC developers to share knowledge and experience of other K-MOOC members.

The NILE Guidelines are developed based on edX’s course development guidelines and require MOOC developers to follow the Korean Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1. The Guidelines have several appendices at the end to help MOOC providers effectively and efficiently manage their course development procedure. The appendices included in the Guidelines are: K-MOOC Development Proposal Form, Copyright and Open Course Agreement Form, Course Design Template, MOOC Content Translation Contract, MOOC Video Shooting Guidelines, Video Lecture Monitoring Checklist and Post-Course Evaluation Survey.

Following the NILE Guidelines, SNU, like other K-MOOC members, has developed its own QA mechanism and designated its CTL to manage the QA process. For the MOOC development, strict QA measures take place across three stages: Design, Development and Final stages. Detailed QA criteria that are developed based on the NILE Guidelines are applied at each stage. CTL invites internal and external experts to evaluate SNU’s MOOCs. CU also follows the NILE Guidelines in developing their K-MOOC.

Table 2

Overview of K-MOOC’s QA Guidelines

| Stages | Areas | Criteria (required highlighted; all others recommended) |

|---|

- Design

| - Learning Content

| - Validity

- Accuracy (required)

- Concreteness

- Learning level

- Amount of content

- Ethical aspect (required)

|

- Instructional Design

| - Learning objectives (required)

- Teaching & learning strategies

- Motivation

|

- Interaction

| - Learner-teacher interaction

- Learner-learner interaction

|

- Support

| - Learning support

|

- Assessment

| - Assessment components

- Assessment methods

- Feedback

|

- NILE evaluation 1

| - Evaluation of MOOC design (required)

|

- Development

| - Video Materials

| - Length of video lecture

- Quality of video images (required)

- Subtitles (required)

|

- Other Materials

| - Texts (required)

- Images (required)

- Documents

|

- Web Accessibility

| - Web accessibility (required)

|

- Copyrights

| - Copyrights (required)

|

- Testing

| - Self-evaluation

| - Self-evaluation

|

- NILE evaluation 2

| - Final evaluation (required)

|

- Testing

| - Pilot testing (platform, LMS, user testing, etc.)

(required) |

- Implementation

| - Support

| - Course information

- Learner management

- Learning support

- Assessment management (required)

- Completion management (required)

|

For each criterion, NILE offers detailed guidelines and suggestions. Let’s review two examples.

Take, for example, the “Amount of content” at the Design stage. The NILE’s QA Guidelines first introduce cases from global MOOC providers and say that expected learning hours per MOOC is between 25 and 125 hours in global MOOCs. In case of edX, average learning hours are set to be around 25 hours per MOOC. But if discussions, simulations or assignments are included, longer learning hours are recommended. In case of a video lecture, around 15 min. per video is recommended to maintain learner attention.

Take another example of “Web accessibility” at the Development stage. Following the Korean Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1, the NILE Guidelines suggest four principles: 1) Perceivable - information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive, 2) Operable - user interface components and navigation must be operable, 3) Understandable - information and the operation of user interface must make sense, and 4) Robust - content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies. The Guidelines then offer specific strategies to apply these four principles in developing a MOOC. For example, for a “perceivable” principle, specific suggestions on alternative content formats to replace texts, alternative media formats to replace multimedia, and strategies to improve clarity of content presentation (e.g., color, size, background, direction, audio level, etc.) are provided.

SNU CTL’s QA Manual for Educational Materials

SNU CTL has developed a faculty manual in both Korean and English to help its faculty members design, develop and utilize SNU’s online course management system[2] called eTL that is linked to SNU’s academic management system. The manual consists of 9 sections:

- Introduction.

- Course Navigation.

- Adding Resources.

- Activities.

- Group.

- Group Activities.

- User Management.

- Attendance Management.

- Grading.

Each section has detailed explanations on how to do things step-by-step with sample screen shots and concrete cases. Along with this manual, periodic faculty development sessions are offered. This manual, along with the manual for SNU students, is used as QA guidelines for (O)ER development and management.

CU CTL’s Strategies for Quality MOOC Study

When developing a MOOC to be serviced on the K-MOOC platform, CU CTL applies the NILE Guidelines. When it comes to promoting the use of K-MOOC or any other educational resources by its students, CU CTL uses two reward mechanisms:

- Mileage System – when students study educational resources such as K-MOOC, KOCW and other materials to develop their own learning competencies outside the classroom, they will then be given certain points of miles which they can exchange for scholarship money.

- SOS (Study of Success) Program – This program financially supports student groups to study MOOCs together to develop their learning competencies.

Related Studies on QA for MOOCs in Korea

Despite the MOOC guidelines offered by NILE, several studies still indicate the quality being an issue in MOOC design in Korea. Lee, Keum, Kim, Choi, and Rha (2016) indicate a lack of appropriate MOOC design models as a reason for inconsistent findings with the quality of MOOCs. They argue that the MOOC-specific instructional design (ID) model is essential to guide design activities considering the unique features of the MOOC. Precedent studies on MOOC design indicate that most of the MOOCs in Korea and elsewhere are developed based on a generic ID model, that is, the ADDIE (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation) model. While this ADDIE model, which has been applied in designing various formats and types of instruction, can guide general design activities of MOOC development, it does not seem to address distinctive characteristics of MOOC teaching and learning.

Below, three studies are discussed that examined unique features of MOOCs and MOOC design principles and models in the context of Korea.

Limet al. (2014) analyzed the procedures engaged in preparation, development and implementation of SNU’s first MOOC on edX and categorized important steps of principal facilitators in MOOC design and delivery. Principal facilitators are leading staff from a MOOC administration team, MOOC support team and MOOC instructors. Four steps include: Agreement, Design and Development, Administration, and Training and Communication.

- The Agreement Stage: As SNU’s MOOCs are developed in agreement with edX, the process of MOOC design begins with “Agreement” which includes basic consensus on such items as infrastructure, administration methods, intellectual property rights, schedule of courses, etc. (edX, 2013a). Once the basic agreement is reached, SNU (through CTL’s committee) selects classes to be developed as SNUx and begins to work with instructors of those classes and discusses schedule, design principles and media, delivery and usage methods, certification and other issues.

- The Design and Development Stage: At this stage, SNU CTL team and instructors discuss a course title, promotion video, overall structure of classes, video lectures and subtitles, learning activities, feedback, TA activities and other design issues.

- The Administration Stage: The next stage would be “Administration” of MOOCs, which is considered the most challenging part as MOOCs often have high enrollment. Helping MOOC learners to go through effective learning processes as smoothly as planned needs careful planning not just for learning support but also for technology support.

- The Training and Communication Stage. Lastly, the “Training and Communication” activities are critical for effective design, development and administration of MOOCs. In particular, periodic training on MOOC authoring tools, learning platform, course design and promotion, regular conduct of meetings via emails or video conferences, and consultation and academic events on MOOC design and research are important for quality design and delivery of MOOCs (edX, 2013b).

While this study offers stages that MOOC developers need to go through while they design and develop a MOOC in collaboration with an external global provider, it does not integrate these four stages into a systemic MOOC design model which can be applied in other contexts.

In another study conducted employing a SWOT analysis method, Lim and Kim (2014) identified seven elements that need to be considered in the design of MOOCs in Korea:

- what is the type of organization that offers MOOCs? (whether the organization is for-profit or non-for profit, public or private university, or global or local provider would affect the MOOC design).

- who are the target learners? (for example, learners’ age, their network environment, and interest would affect the MOOC design).

- content area (depending on the content area – humanities, social sciences, technology, etc. -, the design principles would be different).

- authority to open MOOCs (whether any individual can offer a MOOC or only a certified group or organization can offer a MOOC would affect the MOOC design).

- contract unit (some global MOOC providers only communicate with top universities around the world while other providers work with any types of organizations or individuals, which would affect the MOOC design).

- qualification of the MOOC instructor (who will teach a course and deliver the content would affect the MOOC design). and

- link to a formal credit system (whether MOOC completion is counted as a university or training requirement credit or not would affect the MOOC design).

Unfortunately, the study by Lim and Kim (2014) does not suggest a MOOC design model which considers these seven elements delineated from the SWOT analysis of MOOCs.

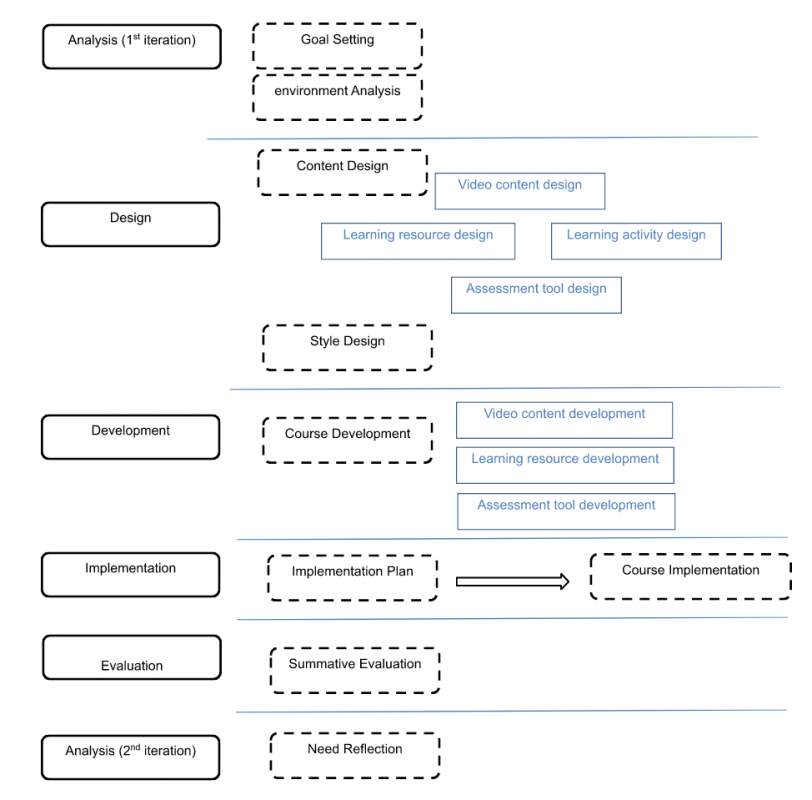

Considering unique features of MOOCs investigated in the previous studies such as the ones analyzed above and other well-established e-learning design models (e.g., Alonso et al., 2005; Jung, 1997; Lee & Owens, 2002), Lee et al. (2016) developed an ID model which can be applied in MOOC design and specified step-by-step activities that would improve the quality of MOOCs in Korea. Through employing the model construction and model validation methodology suggested by Richey and Klein (2007), their study suggests a six-stage MOOC design model consisting of Analysis (first iteration) – Design – Development – Implementation – Evaluation – Analysis (second iteration) as shown in Figure 4.

- At the first Analysis stage, MOOC developers make predictions on learners and identify general purposes at the national, institutional and/or individual levels, and analyze availability and functions of platforms suitable for prospective learners and video shooting competencies.

- At the Design stage, the MOOC developers plan and design various types of MOOC content along with packaging and promotion strategies.

- At the Development stage, the MOOC developers actually produce various types of MOOC content and devise packaging and promotion strategies based on the design plan at the earlier stage.

- At the Implementation stage, they develop a detailed plan for MOOC delivery including timeline, learner supports and feedback and carry out the course based on the plan.

- At the Evaluation stage, they conduct both quantitative and qualitative evaluations. Quantitative data such as assignment completion rate, course completion rate, and academic achievement and qualitative data such as students’ responses and personal goal attainment are collected and fed back to the second analysis stage.

- At the second Analysis stage, the needs of MOOC learners are reviewed based on the data collected during the evaluation stage and course content, assignment and learning support strategies are re-adjusted.

Figure 4

A design model for MOOCs (source: Revised from Lee et al., 2016, p.24)

Japan

JOCW: Decentralized QA Measures

JOCW does not have a set of common QA guidelines or criteria. In principle, each member institution is responsible for setting up its own QA system. In case of UH, OEC uses a set of key performance indicators in creating and implementing OCW and other OER of UH. These indicators[3] are related to well-established ID strategies for online courses. OEC is expected to produce 20 courses for JOCW and 200 OER content items per year and support six or more courses to integrate OER contents for flipped learning.

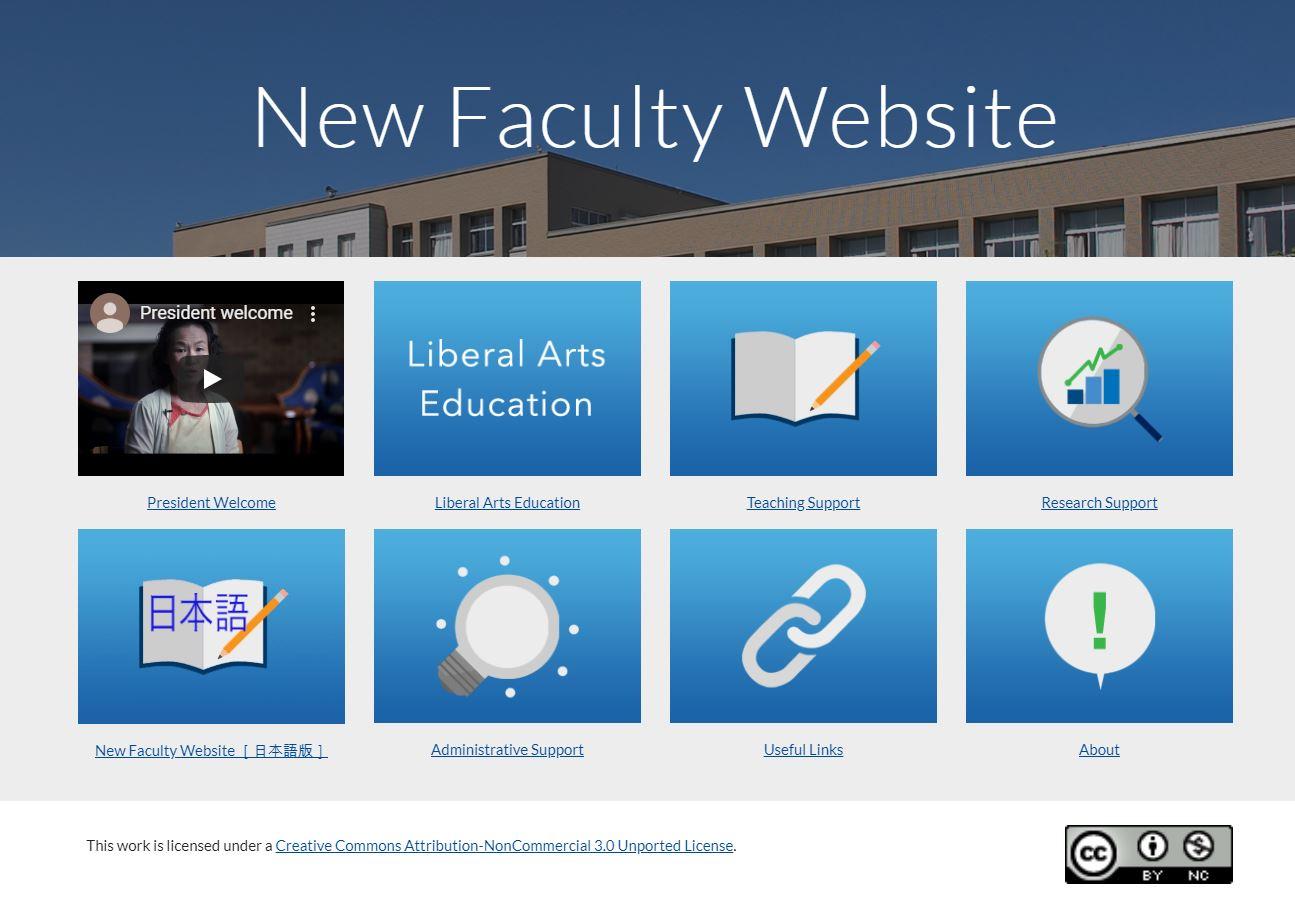

ICU does not have institutional level QA guidelines or criteria for creating its OCW. To develop ICU OCW, CTL contacts individual faculty members across different disciplines who are known to be good teachers and develops some of their class sessions as video clips. Faculty members decide which classes to be recorded. For all new faculty members, CTL offers the new faculty development program, which includes guidelines for syllabus development, various teaching strategies to promote critical thinking and learner engagement, and integration of various types of OER in their class. Various types of content (e.g., texts and video clips) offered in this new faculty development program are developed as OER and thus can be shared with other universities who wish to develop similar kinds of faculty orientation. As for the open campus talks, invited guest lectures, and other conference presentations, ICU’s CTL develops their presentation videos as ICU OCW upon presenters’ permission.

JMOOC: Limited QA System

JMOOC has a committee consisting of three experts in instructional design and online learning from the universities to oversee the quality of MOOCs and examine if the courses fulfill the quality standards as a MOOC. This committee evaluates the course development plans submitted by the universities in advance against a set of QA criteria. JMOOC QA criteria are kept for internal use only and thus could not be obtained for this report. But this evaluation of MOOC plans is an option. If a university submits its MOOC development plan and asks for approval from JMOOC, then it gets funding from JMOOC.

Once a MOOC is developed, the committee will review its overall quality and offer certification if the quality standards are met. Each MOOC is assigned to one of the following three categories:

- University-level courses provided by universities.

- Courses provided by technical colleges and vocational schools, courses recommended by public research institutions, and courses recommended by academic societies.

- Special and extension courses provided by universities, courses provided by companies and enterprises.

Like most of the JMOOC members, UH follows the JMOOC’s QA standards in developing and delivering its MOOCs as explained above.

JMOOC’s QA guidelines do not follow any international e-learning/OER standards specifically, but they are created based on instructional design principles suggested in several studies including the studies discussed below. One of the JMOOC platforms, gacco, offers a student manual to help its MOOC learners study their courses using various functions of the platform. The manual offers useful tips for enrollment, self-test taking, certification and various troubleshooting.

Ichimura and Suzuki (2017), acknowledging the lack of research informing MOOC providers to design high quality of MOOCs, analyzed MOOC-related literature with a focus on the content design of a MOOC and identified common design elements. Studies published on databases such as ERIC and Scopus, journals including Distance Education, and International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (IRRODL), Google Scholar and other relevant sources were included in their analysis. Based on the analysis of these sources, the authors suggested 10 important key elements at two decision stages for quality MOOC design (see Figure 5).

As the Basic Design Decision stage, three dimensions and sub-items are considered:

- Resources such as human and intellectual resources, equipment, and platform need to be carefully analyzed.

- General structures such as course title, language used in the course, platform, domain, target audience, course level, applications (public/blended/flipped, etc.), pace, and accreditation should be carefully decided considering resources the MOOC design team has.

- Vision including course objectives and competencies as results of MOOC learning needs to be clearly stated.

Once the basic decisions are made, the MOOC developers should pay attention to the seven dimensions that are interrelated. The following dimensions ensure that the MOOC is an interactive learning environment:

- Learner Background and Intention including learners' diverse purposes for course engagement and their level of autonomy need to be thoroughly investigated for the selection of content and instructional, motivational and interactional strategies.

- Pedagogy including pedagogical approaches, learning contents, and teaching and learning strategies of the course has to be developed based on learner background information.

- Communication including how learners collaborate and build community in the course needs to be thoroughly designed.

- Assessment including assessment strategies and activities should be planned and developed considering learning objectives, content and learner information.

- Technological Infrastructure including MOOC platform, social media, technical platform of learning analytics, and access methods for course contents, video lectures and resources need to be examined and appropriate technological tools for specific learner groups.

- Learning Analytics Data should be collected. Decisions need to be made regarding types of data to be collected, points of data collection, purposes of data usages, and so on.

- Learning Supports need to be planned based on learner background, content, technology and other information.

Figure 5

Ten dimensions of MOOC design (Source: Revised from Ichimura & Suzuki, 2017, p.47)

Some small-scale consortia have developed their own set of QA guidelines in order to share online courses. For example, a consortium of Shikoku’s five national universities developed the “Instructional Design Guidelines for Common Online Courses” to be applied in efficient online course development in those five member universities (Nemoto, Takahashi, & Takeoka, 2015; Takahashi, 2018). Instructors who develop an online course collaboratively are to review together such documents as an online course plan, an online course content sample written in a common template, an e-learning material sample on the Moodle, a Moodle course template, and a Moodle style sheet. In reviewing these documents, several ID criteria are often applied:

- Basic information (e.g., characteristics of learners, environments, etc.).

- Objectives and assessment.

- Course structure (e.g., content organization and sequencing).

- Content presentation (e.g., explanation, cases, and glossary).

- Practice (e.g., questions, feedback, etc.).

- Media design (e.g., images, video clips, audio, other data).

- Usability (e.g., navigation layout, accessibility, etc.)

Issues Related to OER and QA in OER in Japan

In general, the development and sharing of OER in Japan and QA system is not impressive. Several studies have indicated major issues in OER practices in Japan. A lack of funding is often indicated as a critical issue for the sustainable development of OER. Aoki (2011) points out two funding issues related to OER. One is that there are no private foundations like the Hewlett Foundation that support OER movements in Japan. Another issue is that in many cases, the Japanese government supports individual researchers who develop and study OER, but not HEIs that initiate OER projects. Even if the government funds the institutions, funding ends in a few years and OER projects tend to stop there or disappear.

Related to funding issues, a lack of vision and strategic planning on the development and sharing of educational resources at the national and institutional levels is indicated as a problem for slow OER movements in Japan. Shigeta et al. (2017, p.197) point out that the Japanese government, unlike its counterpart in Korea, does not have OER policy at the national level and its funding for open educational initiatives is quite limited. At the institutional level, as seen in the cases of two Japanese universities, they do not seem to position OER as an integral part of their education and thus do not make a serious effort to develop a strong QA system for their educational resources.

Another serious issue is a lack of skilled ICT personnel and support organizations within a university. Funamori (2017) revealed that almost 95% of Japanese universities surveyed in 2015 reported a lack of staff and insufficient support systems for creating digital content and maintaining infrastructure. He then pointed out that a great deal of effort and budget had been used in creating the catalog, keywords, abstracts, and other metadata in a digital format for databases of Japanese journal articles and bibliographic catalog systems (p.46). Not much contribution has been made for developing and sharing educational resources.

Finally, there is a cultural barrier introducing digital technologies and digital forms of educational resources in Japanese education. As indicated in several studies including Jung and Lee (2015) and Funamori (2017), face-to-face interaction is highly regarded as a most effective and desirable way of instruction and teacher-created materials are greatly valued. Thus, there is a reluctance among educators to introduce e-learning or online learning and use OER that have been created by someone else.

3.4 OER Policy

Korea

Each university in Korea develops its own policy on the development and uses of (open) educational resources ((O)ER). At the institutional level, the Office of Academic Affairs (or another university-level office) is often responsible for policies on (O)ER. At the operational level, the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) in each university plans, develops, disseminates and evaluates (O)ER. Additionally, CTL often works with a committee when it makes major decisions. Participation in the development and utilization of (O)ER is promoted in many universities and is often included as a criterion for faculty evaluation and promotion. The development, utilization and sharing of (O)ER including KOCW and K-MOOC is promoted by Korean MOE and included as one of the criteria in the MOE’s Evaluation of Universities. All universities are affected by this national level policy (Chang, 2015).

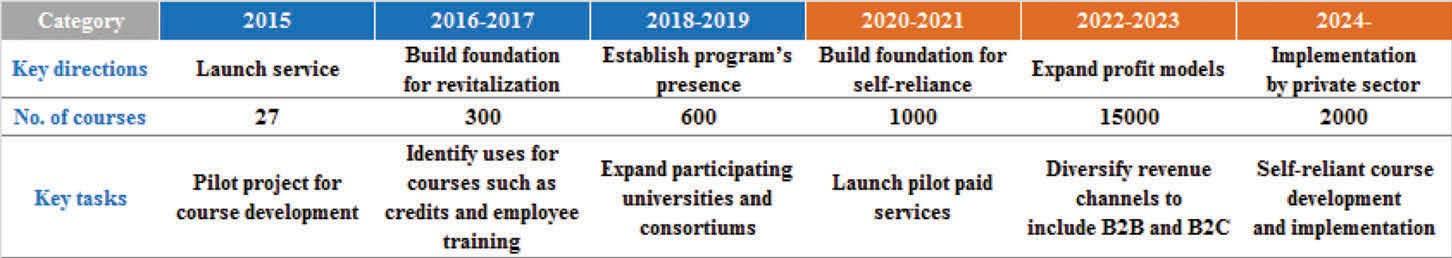

Among various OER, MOOCs have been strongly supported by the MOE and the National Institute for Lifelong Education (NILE), a governmental agency responsible for K-MOOC operation. A road map of K-MOOC[4] implementation created by the MOE and NILE offers key directions and tasks each year as shown in Figure 1 (Lee & Chung, 2019). Phase 1 (2015-2019) focused on the development and stabilization of the system with full government funding. Phase 2 (2020-2024) will see further development of the system and exploration of various business models for self-reliance in the future.

Following this development map, NILE develops more detailed plans and solicits a number of universities for new MOOC applications each year. Considering these plans, universities develop and implement their own policy on K-MOOCs.

- Phase 1: Launch and Establishment 2015-2019

- Phase 2: Advancement and Self-reliance 2020-2024 and so on

Figure 6

A road map for K-MOOC implementation (Retrieved and revised)

Key University Policies

With the increase of K-MOOCs and other (O)ER, policies to promote the use of such online courses and resources have been introduced in many universities in Korea. One such policy is to promote and institutionalize various ways of utilizing online courses and contents in the university courses. For example, strategies such as utilizing online courses/contents for self-directed learning in flipped classrooms, utilizing online courses/contents for blended learning during face-to-face classrooms, introducing completely online courses in the traditional higher education system, and utilizing online courses/contents for remedial or group tutoring sessions (Lee et al., 2016) have been introduced to faculty members via faculty development programs and academic associations’ conferences and seminars. Further, those who participate in the creation and utilization of such online courses and resources are recognized and rewarded during the promotion and evaluation process.

Another policy has been developed to support a collaborative relationship building or a consortium building with other universities and award different types of degrees and certifications to MOOC learners. NILE has recently introduced a new “Series Courses” category in which a set of courses related to the 4th Industrial Revolution are offered together. To apply for this category, universities are required to collaborate or form a consortium with other universities and institutions including four-year universities, two-year colleges, industrial colleges, education universities, Korea National Open University, research institutes, private companies, corporate affiliated research centers, and vocational education and training centers, and non-profit organizations, and create a set of courses under one series course category. For example, under a series course titled “Big Data Analysis with Python”, courses such as Utilizing Python, Data Collection and Modeling, Resources Analysis and Statistics, Mathematical Modeling, and Data Visualization can be offered as a set. These series courses can be more effectively used to create nano-degrees and certifications in collaboration with other partner universities. Considering the evaluation criteria for a series course project (Table 3), several universities have developed policies and guidelines to facilitate collaboration with other academic institutions in the creation and management of series courses and new types of degrees and certification.

Table 3

2019 K-MOOC Evaluation Criteria for a Series Course Project (Korean MOE & NILE, 2019)

| Area | Evaluation Component | Evaluation Criterion |

|---|

| Essentials (20 points in total) | Project Team Structure (10 points) | Applicant institution’s vision and plan for K-MOOC (2 points) |

| Project team’s organization and member composition (4 points) |

| Budget and funding (4 points) |

| Competency of Applicant Institution (10 points) | Experience with OCW or online course development and implementation in related fields (5 points) |

| Applicant institution’s specialization in related fields (5 points) |

| Course Development (60 points in total) | Selection of Courses (15 points) | Needs for a Series Course Development (10 points) |

| Systematic Offering of Courses (5 points) |

| Course Content and Structure (30 points) | Course content (15 points) |

| Instructional design and interaction strategies (10 points) |

| Assessment strategies (5 points) |

| Instructor (15 points) | Instructor’s expertise and reputation (10 points) |

| Instructor’s teaching competency (5 points) |

| Course Implementation and Utilization (20 points in total) | Course Implementation (10 points) | Course quality assurance plan (5 points) |

| PR plan (5 points) |

| Course Utilization (10 points) | Course utilization plan (10 points) |

| Total (100 points) |

Moreover, a policy to link MOOCs to the national Academic Credit Bank System (ACBS) has also been institutionalized in the universities that offer K-MOOCs. ACBS is an open higher education system which recognizes diverse learning experiences acquired from in- and outside-school settings. Learners can acquire credits through various education and job training institutes, part-time enrollment in traditional universities, certification acquisition from MOOCs and other lifelong education courses, and passing the Bachelor’s Degree Examination program for self-education (Fulbright U.S. Education Center, 2008). Once the learner accumulates the necessary approved credits, he/she can be awarded a degree.

Another important policy guideline related to copyrights of (O)ER has been developed. The universities that are selected as a K-MOOC provider use a consent form created by NILE (Table 4). Following the detailed guidelines provided by NILE, universities have refined their existing copyright-related policies and have educated their faculty members not to use the copyrighted materials without written permission from the copyright holders, and if possible to only use those materials in the public domain or with open license (NILE, 2019).

Table 4

K-MOOC and KOCW: Copyright and Consent Form (created by NILE)

| Year of Development | | Number of Enrollment | |

| Course Title | |

| Applicant | Name | Affiliation | Contact |

| | | |

| Content Overview | Creative Commons License | - by

- by-nd

- by-sa

- by-nc

- by-nc-nd

- by-nc-sa

- Default: "by-nd"

|

| Content Classification | Macro | |

| Meso | |

| Micro | |

| Course Outline | |

- This course does not include any copyrighted materials without permission.

- Copyright and ownership of this course belong to the participating faculty member and the university.

- This course will be used for K-MOOC and KOCW.

Date: Applicant: (signature) |

Two Cases: Policy Directions and Actors Involved

In the case of Seoul National University (SNU), depending on the types of (O)ER, three different policy frameworks for selection and management exist: 1) for internal courses, 2) for K-MOOCs, and 3) for global MOOCs, that is, edX.

To support the internal courses offered to SNU students (or sometimes open to the general public or community members), CTL, which is positioned under the Office of Academic Affairs, receives applications from faculty members in a wide range of majors and selects a certain number of courses considering its capacity to support (O)ER development. Two types of resources are often supported. One type is the development of a set of online video lectures to be used for blended or flip learning during regular classroom-based courses. In this case, each video lecture is composed of 15 – 20 minutes. Another type is the creation of a totally online course for faculty members who wish to offer their courses completely via the internet. While CTL works closely together with faculty members and their teaching assistants in developing these online resources, it also offers a series of workshops for faculty and TAs to develop competencies in such areas as producing a video lecture, introducing flip learning, coaching, using an LMS, and other teaching strategies.

To support the courses that will be provided as K-MOOCs, CTL receives applications from faculty members. As these courses will be open to the public and represent SNU’s education as K-MOOCs, the selection procedure is stricter than that of the internal courses. One of the most important criteria is the subject matter. Courses that show high demand from the general public and are expected to have high learning impacts are often selected as K-MOOCs as the Korean MOE and NILE emphasize and prioritize the courses related to topics of the 4th Industrial Revolution. So far, such courses as Youth Psychology, Happiness Psychology, Micro Economics, The Analects of Confucius and Modern Society, Language and Human, Understanding Religious Symbols, Reading Nietzsche, Data Mining, Humanoid Robot, Drone - From Principles to Programming, Robotics, Counselling, Contact Lenses: Selection and Fitting, Robot Manipulator and Underwater Robot, etc. have been developed and disseminated as K-MOOCs. Quality guidelines for K-MOOCs developed by NILE are applied in the development and management of these courses.

For edX courses, CTL does not develop new courses for edX from scratch. Instead, it selects a few courses from internal online courses and K-MOOCs and revises them for the purpose of edX courses. In selecting such courses, it considers whether the courses can represent the quality of SNU education and if they have shown high learner satisfaction.

During the process of establishing and implementing policies related to (O)ER development and use, several committees and teams are involved. Following the policy directions of the university, CTL works with the Curriculum Committee in making decisions on CTL activities. Within CTL, three teams work closely together to implement such decisions: 1) Instructional Team, 2) Development Team and 3) Planning & Support Team.

- The Instructional Team is responsible for the design, development and management of online content and online courses together with faculty members and TAs.

- The Development Team produces high quality online content and courses often in collaboration with external e-learning companies.

- The Planning and Support Team manages the selection and planning process for online contents and courses, communicates with NILE regarding K-MOOCs and edX on edX courses, evaluates and approves digital contents developed by the Development Team and external companies, manages internal online courses and supports the Instructional Team.